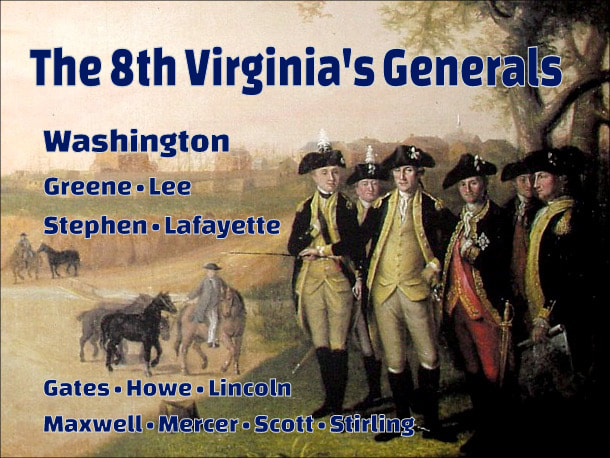

Cooper was the lieutenant commandant, or “captain lieutenant,” of Col. John Neville’s company of the 4th Virginia Regiment. This was a new rank for the Continental Army modeled on British practice that resulted from a cost-saving reduction in the number of officers. As the regiment’s senior lieutenant, Cooper led a company nominally under the direct command of the colonel. Perhaps Abraham Kirkpatrick, the man who shot him, thought Cooper was putting on airs. Whatever his reason, Kirkpatrick was clearly the aggressor. He attacked Cooper with a stick. Cooper apparently had a more peaceful temperament and showed no “disposition to demand satisfaction.” The era’s code of honor, however, required him to make the challenge. His peers could not abide Cooper’s reluctance to stand up for himself and told him that “unless he did, he must leave the Regiment, as they were Determined he should not rank as an Officer.” Cooper reluctantly complied. He and Kirkpatrick faced off with pistols and the hapless lieutenant took a ball of lead to his leg. The limb was amputated and he was transferred to the Corps of Invalids. He was one of the very last men discharged from the army at the end of the war. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

3 Comments

Professor Muñoz argues persuasively, however, that scholars, lawyers, and judges have all done a consistently sloppy job of seeking to understand what the founders actually meant by the words they used. So much so, in fact, that the original meaning of the Establishment and Free Expression clauses has effectively been lost. The result is that the text has become an ideological Rorschach test. It can be made to mean almost anything. “The consensus that the Founders’ understanding should serve as a guide has produced neither agreement nor coherence in church-state jurisprudence,” Dr. Muñoz writes. “Indeed, it has produced the opposite; it seems that almost any and every church-state judicial position can invoke the Founders’ support. Many readers will be surprised to hear that the Founders themselves are largely to blame for this. The language of the First Amendment itself (“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof”) is not very precise. The reason for this is that “Many, if not most, of the individuals who drafted the First Amendment did not think it was necessary.”[2] Establishment was a state issue and the Federal constitution already banned religious tests in Article VI.[3] It was the Anti-Federalists who insisted on the Bill of Rights, but they were in the minority in the 1st Congress. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

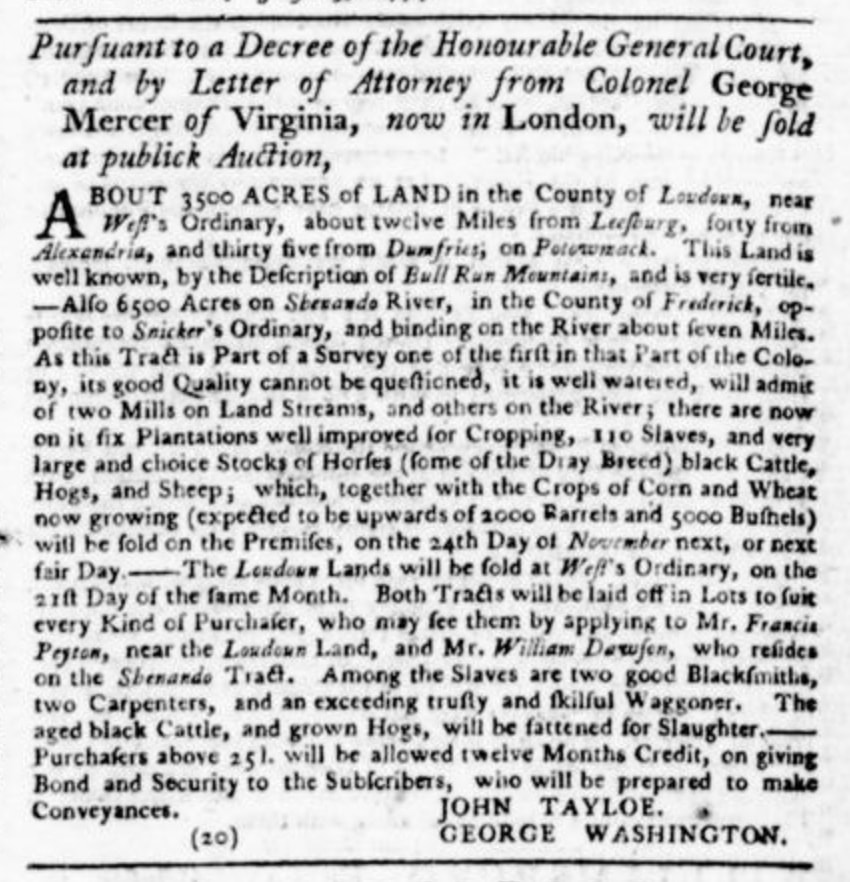

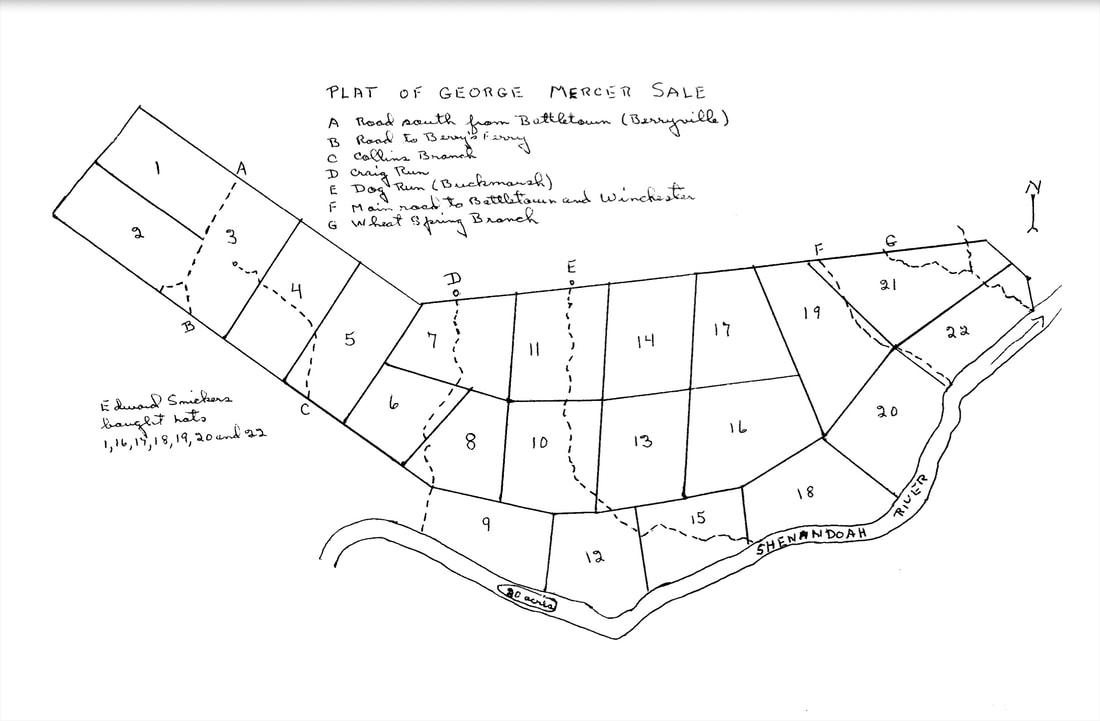

At the peak of his career, Mercer was selected by the Ohio Company of land speculators to represent their interests in London. The hated 1765 Stamp Act was enacted by Parliament while he was traveling. Not fully aware of sentiments at home, he accepted an appointment as Stamp Master for Virginia. He was overtaken by a mob and forced to resign when he returned to Virginia. Though the cheering crowd carried him out of the capitol in Williamsburg in celebration, Mercer soon left the colony for good.

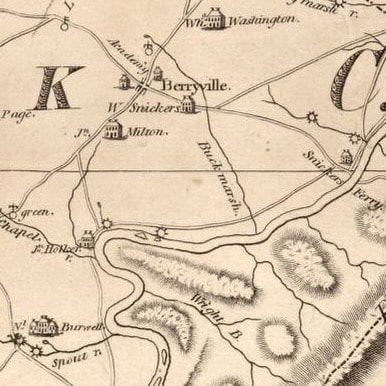

Less than two years later, the Frederick Committee of Safety chose Thomas to lead a new company of Provincial soldiers, which was then assigned to the 8th Virginia Regiment. He continued to lead his men until their enlistments expired at Valley Forge in April of 1778 and then returned home to lead what appears to have been a quiet life. He died in 1818. Benjamin, the older brother, was the founder of Berryville—a town just north and west of the old Mercer property. Benjamin is better remembered because of his namesake town, but Thomas’s military service deserves to be remembered as well. Read More: "Lost & Found: James Kay & Thomas Berry" More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

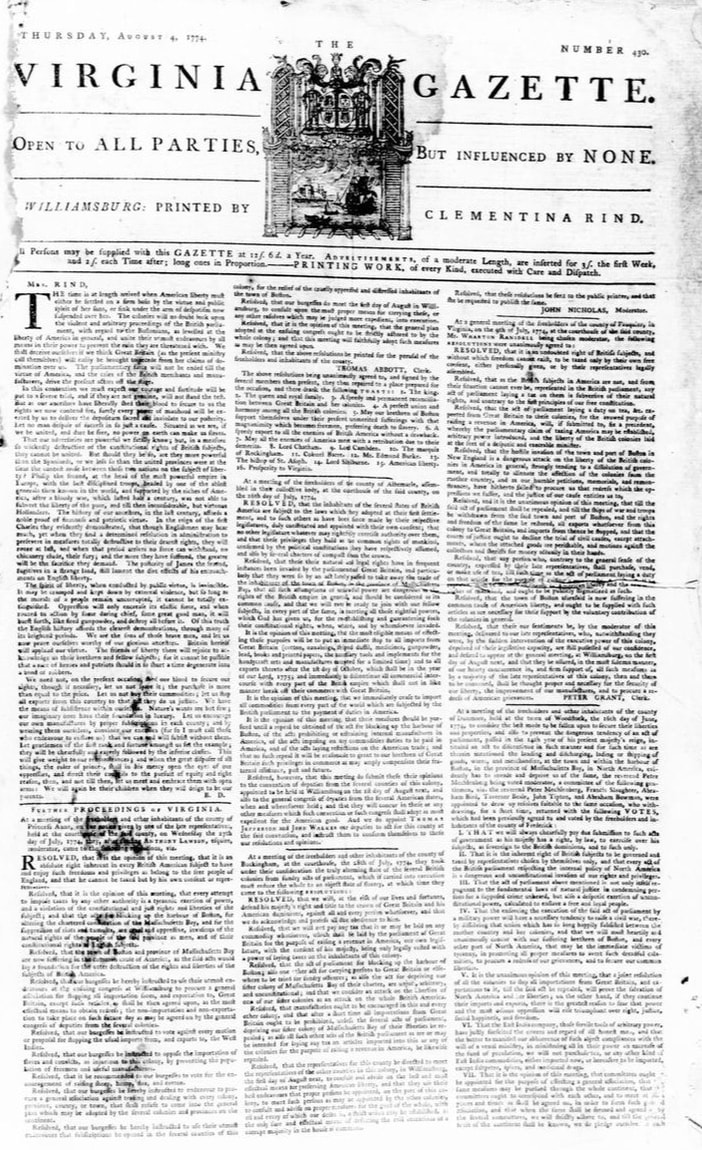

Virginia, Britain’s oldest and biggest American colony, had charter territory reaching all the way to the Mississippi. While the colony made a genuine effort to respect Indian rights by barring western settlement on land not acquired by treaty, individual settlers ignored these restraints. In 1768, the Treaty of Fort Stanwix extended the settlement line to the Ohio River and opened what are now Kentucky and trans-Appalachian West Virginia to settlement. The treaty was made with the Iroquois, who claimed authority over the region. However, the tribes who actually lived there objected and in 1774 that lead to war. Tensions were also starting to boil over between the colonies and the Great Britain. Most Americans strongly objected to Parliament’s levying of “internal” taxes on the colonies because they had no elected representation in London. Parliament clamped down hard on Massachusetts after the Boston Tea Party by blockading Boston Harbor and taking other measures.

More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

He described the priest’s ornate vestments, the beautiful music, and the bloody crucifix above the altar. “Here is every Thing which can lay hold of the Eye, Ear, and Imagination. Every Thing which can charm and bewitch the simple and ignorant. I wonder how Luther ever broke the spell.” He admitted, though, that the sermon was good. Protestants’ views of Catholics aside, it was the Church itself, and more specifically the Papacy, that presented a problem for the British Empire. The influential political thinker John Locke asserted in his 1689 Letter Concerning Toleration that a “church can have no right to be tolerated by the magistrate, which is constituted upon such a bottom, that all those who enter into it . . . deliver themselves up to the protection and service of another prince.”[3] By tolerating such a church, a ruler would “suffer his own people, to be lifted, as it were, for soldiers against his own government.”[4] The example he used was Islam, but it was Catholicism he was concerned about. Michael Breidenbach is a Cambridge University-educated associate history professor at Ave Maria University, an orthodox Catholic school in Florida. His book Our Dear-Bought Liberty: Catholics and Religious Toleration in Early America illustrates the remarkably rapid transformation of Americans’ treatment of Catholics during the Founding Era. Irish Catholics like Capt. John Barry, Lt. Col. John Fitzgerald, and Col. Stephen Moylan played important roles in the Continental Navy and Army. Maryland’s Charles Carroll signed the Declaration of Independence and held a seat on the Continental Congress’s powerful Board of War. Generals Lafayette and Pulaski were both Catholic, as were the French and Spanish empires that came to America’s aid. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

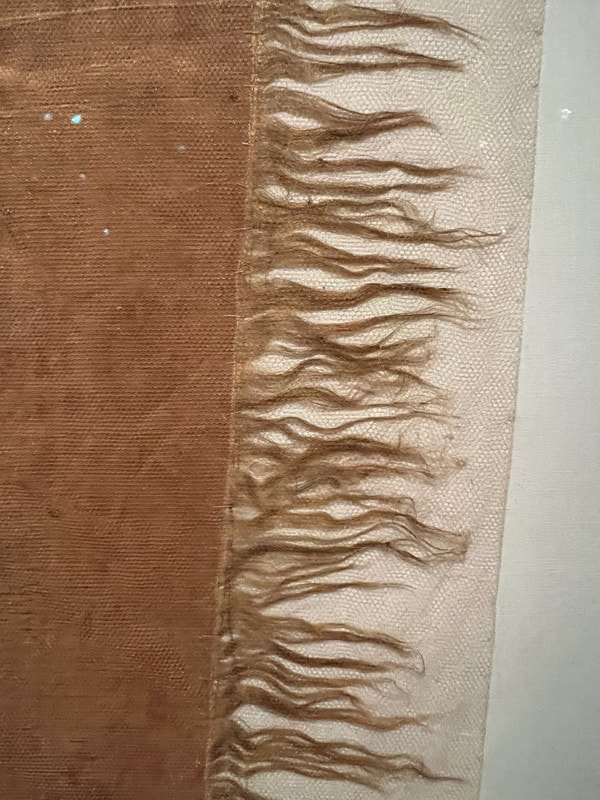

While the Grand Union flag and the Stars and Stripes may have appeared on some battlefields, they were more likely to be seen on forts and ships. Virginia had no state flag until the Civil War. Every regiment, however, had a flag that served important symbolic and battlefield purposes. Regimental flags were unique works of art, often featuring symbols from antiquity or popular culture with mottos in English or Latin. The flags of the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment and Connecticut’s 2nd Continental Light Dragoons are among the very few that survive. There is, however, an 8th Virginia flag that still exists—but it is not the regimental banner. It is a “grand division standard,” one of two that were used to direct halves of the regiment on the battlefield. These were utilitarian devices with little ornamentation. The most important thing about them was their color.

Henry A. Muhlenberg was at that time preparing to publish a biography of his great uncle, the still-useful (but occasionally inaccurate) Life of Major-General Peter Muhlenberg of the Revolutionary Army. The younger Muhlenberg was a member of Congress and quite knowledgeable about his pedigree, but his description of the flag as “the regimental color” was wrong.

"In 2012, the flag was sold at Freeman’s Auction in Philadelphia. Prior to the auction, Freeman’s brought it to Shenandoah County to be displayed. I was lucky that I found out about it just a couple of days prior to the event. I contacted my friend Erik [Dorman] who also was interested in writing about the 8th and we decided to show up in our uniforms. We caused quite a stir when we walked around the corner of the Courthouse into the square. We were immediately enlisted to "guard" the flag and unveil it during the event.”

With it were two smaller, plainer flags of identical design but different colors. The 3rd Detachment was an ad hoc unit cobbled together under Col. Abraham Buford in 1780 from new recruits and soldiers who had avoided capture at Charleston earlier that year. The flags were used at the Waxhaws in South Carolina on May 29 when Tarlton defeated Buford there. It is unlikely that the flags were made specifically for the detachment. The regimental flag is described in detail in a 1778 inventory of then-new flags known as the “Gostelowe Return.” The flags were probably, therefore, inherited from a regiment that was folded into Buford’s detachment. Buford had been colonel of the 11th Virginia, and a number of the men in his detachment were reportedly from the 2nd Virginia. The flag could have come from either of those, or from another. The two “grand division” flags from the Buford detachment are almost identical, except for their colors, to the Muhlenberg flag. Buford’s maneuvering flags are blue and yellow. The Muhlenberg flag is a beige color today and was described as a “salmon” color in 1847. A fabric expert advises that the original color was red. The flag has faded considerably just from its time in the frame. It is not hard to imagine it having faded from red to a salmon color over the century or so before it put under glass. The scrolls on the blue and yellow flags contain only the word "regiment." The word is not centered in the scroll, suggesting that a space was retained to the left on both flags to be filled in when they were assigned to a specific regiment. The writing in the 8th Virginia's scroll is illegible now. It was retouched on one side by Mr. Goetz or a previous owner to say "VIII Virg Regt." The 1847 account in the Richmond Whig says the scroll was styled a bit differently as "VIII Virga Regt."

More from The 8th Virginia RegimentSeveral counties proceeded to draft "resolves" or resolutions asserting their rights and proclaiming their loyalty to King George III in a sometimes subtly conditional way. Among them was the following declaration from Dunmore County, which was selected from the many at hand by Mrs. Rind for publication. It was drawn up by a committee chaired by Rev. Peter Muhlenberg, the future colonel of the 8th Virginia. Also on the committee were future lieutenant colonel Abraham Bowman, future lieutenant Taverner Beale, and the brother of future captain George Slaughter. They borrowed the text from neighboring Frederick County. The two counties had a shared history: Dunmore was carved out of Frederick in 1772. Muhlenberg may also have felt comfortable borrowing the text in part because Frederick's committee was similarly led by an Anglican clergyman: Rev. Charles Mynn Thruston. Rind misspelled Muhlenberg's name two different ways, indicating that he was not yet well known in Williamsburg. The word "votes" was set in capital letters where the word "resolves" would make more sense—another apparent error. Dunmore County was renamed "Shenandoah" County during the Revolution. Only one other 8th Virginia county issued resolves that summer. Culpeper County produced its document on July 7, but the text is evidently lost. The document below predates both the First Virginia Convention and the First Continental Congress. More counties issued resolutions after the First Continental Congress adopted the Articles of Association, formalizing a uniform boycott and calling upon county committees in all of the colonies to enforce it. Augusta, Berkeley, Fincastle, and Hampshire counties issued resolutions 1775 and raised companies for the 8th Virginia the following spring. The resolutions from Augusta and Fincastle survive. Fincastle's resolution is famous for being the first to openly threaten war. The Dunmore ResolvesAt a meeting of the freeholders and other inhabitants of the county of Dunmore, held at the town of Woodstock, the 16th day of June, 1774, to consider the best mode to be fallen upon to secure their liberties and properties, and also to prevent the dangerous tendency of an act of parliament, passed in the 14th year of his present majesty’s reign, intituled an act to discontinue in such manner and for such time as we therein mention the landing and discharging, lading or shipping of goods, wares, and merchandize, at the town and within the harbour of Boston, in the province of Massachusetts Bay, in North America, evidently has to invade and deprive us of the same, the reverend Peter Mechlenberg being voted moderator, a committee of the following gentlemen, viz. the reverend Peter Mechlenberg, Francis Slaughter, Abraham Bird, Taverner Beale, John Tipton, and Abraham Bowman were appointed to draw up resolves to the same occasion, who withdrawing, for a short time, returned with the following VOTES, which had been previously agreed to and voted by the freeholders and inhabitants of the county of Frederick:

More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

Samuel Brady of the 8th Pennsylvania was a military legend in his own time and the stories of at least some of his exploits have likely been embellished in the retelling. The Biggs and Brady families lived within two miles of each other and were, according to Brady's son, "always o the most intimate term." This story appeared in Graham's Illustrated Magazine in February 1857. The Philadelphia-based magazine did not identify the author. The story is dramatically told, betraying at least some artistic license. There are also some small identifiable inaccuracies (Col. Daniel Brodhead is called "General Richard Brodhead"). While some skepticism is warranted about its details, there is no reason to doubt that the story's basic elements are true. The story was instantly popular, reappearing in numerous publications through the 1880s. Biggs went on to become a general of Virginia militia, playing a role in suppressing the Whiskey Rebellion in 1792. At roughly the same time, Brady was tried in court for murdering Indians, but he was acquitted by the jury. The Knife and TomahawkAn Unpublished Incident in the Life of Capt. Samuel Brady |

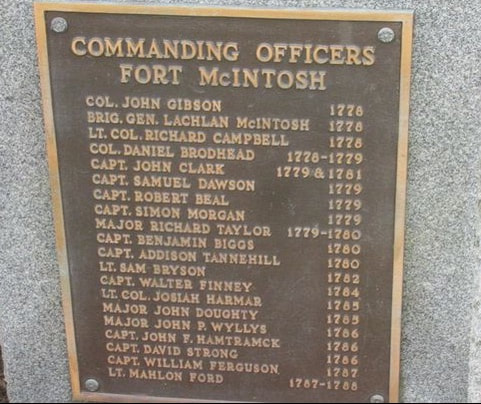

| About thirty miles below the present city of Pittsburg, stood an ancient fort, known as Fort McIntosh. It was built by a revolutionary general of that name, in the summer of 1778. It was one of a line of forts, which was intended to guard the people who lived south of the Ohio river, from the incursions of the savages to the northward. This fort was one of the favorite resorts of the great Indian spy and hunter, Captain Samuel Brady. Although his usual head-quarters: was Pittsburg, then consisting of a rude fort and a score or two of rough frontier tenements. Brady had emigrated westward, or rather had marched thither in 1778, as a lieutenant in the distinguished Eighth Pennsylvania Regiment, under the command of General Richard Broadhead, of Easton. When, in the spring of 1779, McIntosh retired from command in the West, Broadhead succeeded him, and remained at Pittsburg until 1781. Shortly after his advent to the west, Brady was brevetted Captain. |

| Having premised this much by way of introduction, it brings us to the opening of our story. On the 2lst day of August, 1779, Brady set out from Fort McIntosh, for Pittsburg. He had with him two of his trusty and well-tried followers. These were not attached to the regular army, as he was, but were scouts and spies, who had been with him upon many an expedition. They were Thomas Bevington and Benjamin Biggs. Brady resolved to follow the northern bank of the Ohio. Biggs objected to this, upon the ground, as Brady well knew, that the woods were swarming with savages. Brady, however, had resolved to travel by the old Indian path, and having once made up his mind, no consideration could deter him from carrying out his determination. Bevington had such implicit faith in his ability to lead, that he never thought of questioning his will. |

But, as they approached the edge of the clearing, just outside of the fence, Brady discovered “Indian signs,” as he called them. His companions discovered them almost as quick as he, and at once, in low tones, communicated to each other the necessity for a keen watch. They slowly trailed them along the side of the fence toward the house, whose situation they well knew, until they stood upon the brow of the bluff bank which overlooked it. A sight of the most terrible description met their eyes. The cabin lay a mass of smouldering ruins; from whence a dull blue smoke arose in the clear August sunshine. They observed closely everything about it. Brady knew it was customary for the Indians after they had fired a settler’s cabin, if there was no immediate danger, to retire to the woods close at hand, and watch for the approach of any member of the family who might chance to be absent when they made the descent. Not knowing but that they were even then lying close by, he left Bevington to watch the ruins, lying under cover, whilst he proceeded to the northward, and Biggs southward, to make discoveries. Both were to return to Bevington, if they found no Indians. If they came across the perpetrators, and they were too numerous to be attacked regularly, Brady declared it to be his purpose to have one fire at them, and that it should be a signal for both of his followers to make the best of their way to the fort.

| All this rapidly transpired, and with Brady to decide, was to act. As he stole cautiously round to the northern side of the inclosure, he heard a voice in the distance singing. He listened keenly, and soon discovered from its intonations, that it was a white man’s. He passed rapidly in the direction whence the sound came. As it approached, he concealed himself behind the trunk of a large tree. Presently a white man, riding a fine horse, came slowly down the path. The form was that of Albert Gray, the stalwart, brave, devil-may-care settler, who had built him a home miles away from the fort, where no one would dare to take a family, except himself. |

Gray, with the instinctive feeling of one who knew there was danger, and with that vivid presence of mind which characterizes those acquainted with frontier life, ceased at once to struggle. The horse had been started by the sudden onslaught, and sprung to one side. Ere he had time to leap forward, Brady had caught him by the bridle. His loud snorting threatened to arouse any one who was near. The Captain soon soothed the frightened animal into quiet.

Gray now hurriedly asked Brady what the danger was. The strong, vigorous spy, turned away his face unable to answer him. The settler’s already excited fears were thus turned into realities. “The manly form shook like an aspen leaf, with emotion—tears fell as large drops of water over his bronzed face. Brady permitted the indulgence for a moment, whilst he led the horse into a thicket close at hand and tied him. When he returned Gray had sunk to the earth and great tremulous convulsions writhed over him. Brady quietly touched him upon the shoulder and said, “Come.” He at once arose, and had gone but a few yards until every trace of emotion had apparently vanished. He was no longer the bereaved husband and father—he was the sturdy, well-trained hunter, whose ear and eye were acutely alive to every sight or sound, the waving of a leaf or the crackling of the smallest twig.

He desired to proceed directly toward the house, but Brady objected to this, and they passed down toward the river bank. As they proceeded, they saw from the tracks of horses and moccasin prints upon the places where the earth was moist, that the party was quite a numerous one. After thoroughly examining every cover and possible place of concealment, they passed on to the southward and came back in that direction to the spot where Bevington stood sentry. When they reached him they found that Biggs had not returned. In a few minutes he came. He reported that the trail was large and broad; the Indians had taken no pains to conceal their tracks—they simply had struck back into the country, so as to avoid coming in contact with the spies whom they supposed to be lingering along the river.

| The whole four now went down to the cabin and carefully examined the ruins. After a long and minute search, Brady declared in an authoritative manner, that none of the inmates had been consumed. This announcement at once dispelled the most harrowing fears of Gray. As soon as all that could be discovered had been ascertained, each one of the party proposed some course of action. One desired to go to Pittsburg and obtain assistance—another thought it best to return to McIntosh and get some volunteers there—Brady listened patiently to both these propositions, but arose quickly, after talking a moment apart with Biggs, and said, “Come.” Gray and Bevington obeyed at once, nor did Biggs object. Brady struck the trail and began pursuit in that tremendous rapid manner for which he was so famous. It was evident that if the savages were overtaken, it could only be done by the utmost exertion. They were some hours ahead, and from the number of their horses must be nearly all mounted. Brady felt that if they were not overtaken that night, pursuit would be utterly futile. It was evident that this band had been south of the Ohio and plundered the homes of other settlers. They had pounced upon the family of Gray upon their return. |

At last, convinced from the general direction in which the trail led, that he could divine with absolute certainty the spot where they would ford that stream, he abandoned it and struck boldly across the country. The accuracy of his judgment was vindicated by the fact, that from an elevated crest of a long line of hills, he saw the Indians with their victims just disappearing up a ravine on the opposite side of the Beaver. He counted them as they slowly filed away under the rays of the declining sun. There were thirteen warriors, eight of whom were mounted—another woman, besides Gray’s wife, was in the cavalcade, and two children besides his—in all, five children.

The odds seemed fearful to Biggs and Bevington; although Brady made no comments. The moment they had passed out of sight, Brady again pushed forward with unflagging energy, nor did his followers hesitate. There was not a man among them whose muscles were not tenseand rigid as whip-cord, from exercise and training, from hardship and exposure. Gray’s whole form seemed to dilate into twice its natural size at the sight of his wife and children. Terrible was the vengeance he swore.

Just as the sun set, the spies forded the stream and began to ascend the ravine. It was evident that the Indians intended to camp for the night some distance up a small creek or run, which debouches into Beaver River, about three miles from the location of Fort McIntosh, and two below the ravine. The spot, owing to the peninsular form of the tongue of the land lying west of the Beaver, at which they expected to encamp, was full ten miles from that fort. Here there was a famous spring, so deftly and cunningly situated in a deep dell, and so densely inclosed with thick mountain pines, that there was little danger of discovery! Even they might light a fire and it could not be seen one hundred yards.

The proceedings of their leader, which would have been totally inexplicable to all others, were partially, if not fully, understood by his followers. At least, they did not hesitate or question him. When dark came, Brady pushed forward with as much apparent certainty as he had done during the day. So rapid was his progress, that the Indians had but just kindled their fire and cooked their meal, when their mortal foe, whose presence they dreaded as much as that of the small-pox, stood upon a huge rock looking down upon them.

His party had been left a short distance in the rear, at a convenient spot, whilst he went forward to reconnoitre. There they remained impatiently for three mortal hours. They discussed in low tones the extreme disparity of the force—the propriety of going to McIntosh to get assistance. But all agreed that if Brady ordered them to attack, success was certain. However impatient they were, he returned at last.

| He described to them how the women and children lay within the centre of a crescent formed by the savages as they slept. Their guns were stacked upon the right, and most of their tomahawks. The arms were not more than fifteen feet from them. He had crawled within fifty feet of them, when the snortings of the horses, occasioned by the approach of a wild beast, had aroused a number of the savages from their light slumbers, and he had been compelled to lie quiet for more than an hour until they slept again, |

After each fairly understood the duty assigned him, the slow, difficult, hazardous approach began. They continued upon their feet until they had gotten within one hundred yards of the foe, and then lay down upon their bellies and began the work of writhing themselves forward like a serpent approaching a victim. They at last reached the very verge of the line, each man was at his post, save Biggs, who had the farthest to go. Just as he passed Brady’s position, a twig cracked roughly under the weight of his body, and a huge savage, who lay within the reach of Gray’s tomahawk, slowly sat up as if startled into this posture by the sound. After rolling his eyes, he again lay down and all was still.

Full fifteen minutes passed ere Biggs moved; then he slowly went on. When he reached his place, a very low hissing sound indicated that he was ready, Brady in turn reiterated the sound as a signal to Gray and Bevington to begin. This they did in the most deliberate manner. No nervousness was permissible then. They slowly felt for the heart of each savage they were to stab, and then plunged the knife. The tomahawk was not to be used unless the knife proved inefficient. Not a sound broke the stillness of the night as they cautiously felt and stabbed, unless it might be that one who was feeling would hear the stroke of the other’s knife and the groan of the victim whom the other had slain. Thus the work proceeded. Six of the savages were slain. One of them had not been killed outright by the stab of Gray. He sprang to his feet, but as he arose to shout his war cry, the tomahawk finished what the knife had begun. He staggered and fell heavily forward, over one who had not yet been reached. He in turn started up, but Brady was too quick, his knife reached his heart and the tomahawk his brain almost at the same instant.

All were slain by the three spies, except one. He started to flee, but a rifle shot by Biggs rang merrily out upon the night air and closed his career. The women and children, alarmed by the contest, fled wildly to the woods; but when all had grown still and they were called, they returned, recognizing amid their fright the tones of their own people. The whole party took up their march for McIntosh at once. About sunrise next morning the sentries of the fort were surprised to see the cavalcade of horses, men, women and children, approaching the fort. When they recognized Brady, they at once admitted him and the whole party,

| In the relation of the circumstances afterward, Bevington claimed to have killed three and Gray three. Thus Brady, who claimed nothing, must have slain at least six, whilst the other two slew as many. The thirteenth Biggs shot. From that hour to this, the spring is called the “Bloody Spring!” and the small run is called, ‘‘Brady’s Run.” Few, even of the most curious of the people living in the neighborhood, know aught of the circumstances which conferred these names; names which will be preserved by tradition forever. Thus ended one of the very many hand-to-hand fights which the great spy had with the savages. His history is fuller of daring incident, sanguinary, close, hard contests, perilous explorations and adventurous escapes, than that of either of the Hetzels, of Boone or Kenton. He saw more service than any of them, and his name was known as a bye-word of terror among the Indian tribes, from the Susquehanna to Lake Michigan. |

More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

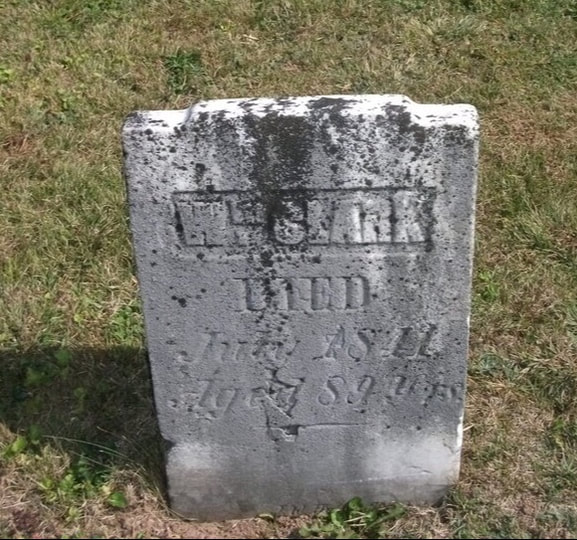

A lichen-encrusted wooden grave marker in a Shenandoah Valley graveyard.

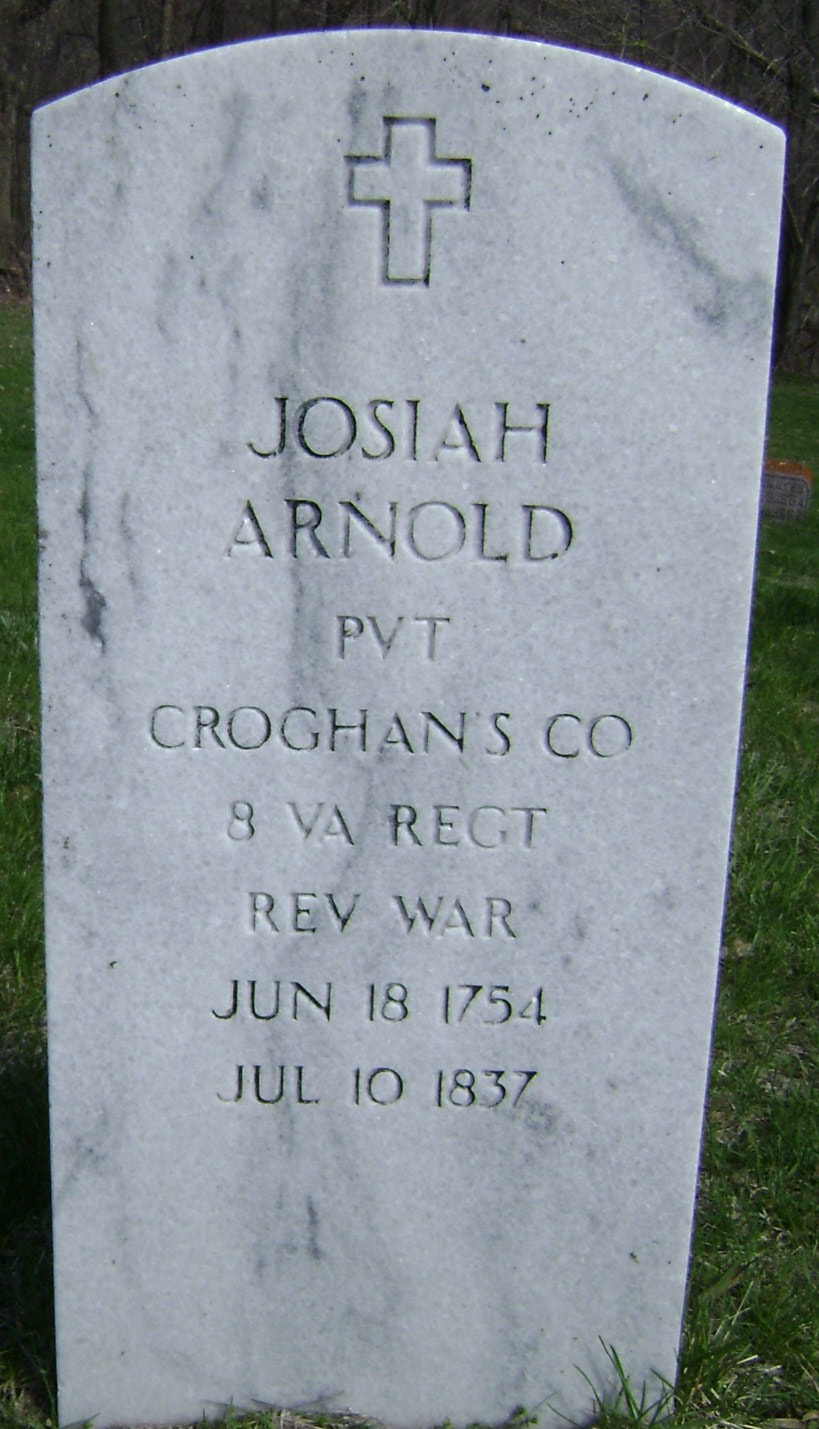

A lichen-encrusted wooden grave marker in a Shenandoah Valley graveyard. | Pvt. Josiah Arnold was born in 1754 and enlisted in Capt. William Croghan's company in March of 1776, He was wounded at the Battle of Germantown in 1777 and discharged at Valley Forge in 1778. He married Judith Dougherty and moved to Muhlenberg County, Kentucky in 1819. He died in 1837 and is buried in Petersburg, Indiana. |

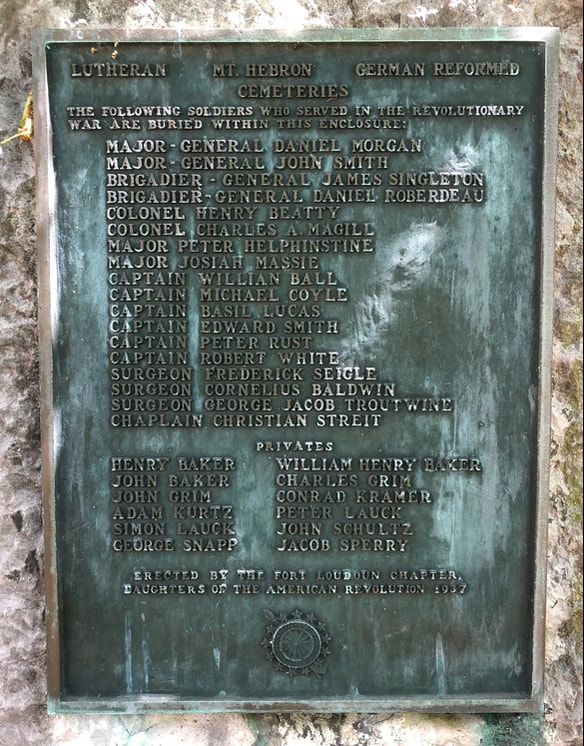

| Surgeon Cornelius Baldwin was appointed to serve the 8th Virginia in May of 1777 and continued with the Continental Army after the regiment was folded into the 4th Virginia Regiment. He was born in Elizabeth, New Jersey and may have studied at the College of New Jersey (Princeton), but did not graduate. He may have studied medicine under Dr. Benjamin Rush in Philadelphia. He established the army hospital at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. he was taken prisoner with the Virginia line at the surrender of Charleston in 1780. He was exchanged and returned to the army, serving at Fort Pitt and Winchester. After the war he settled in Winchester and practiced medicine there until his death in 1826. He was buried in the "old Presbyterian cemetery," but reinterred in Mount Hebron Cemetery in 1912. His home survived. Mary Baldwin College is named for his granddaughter. |

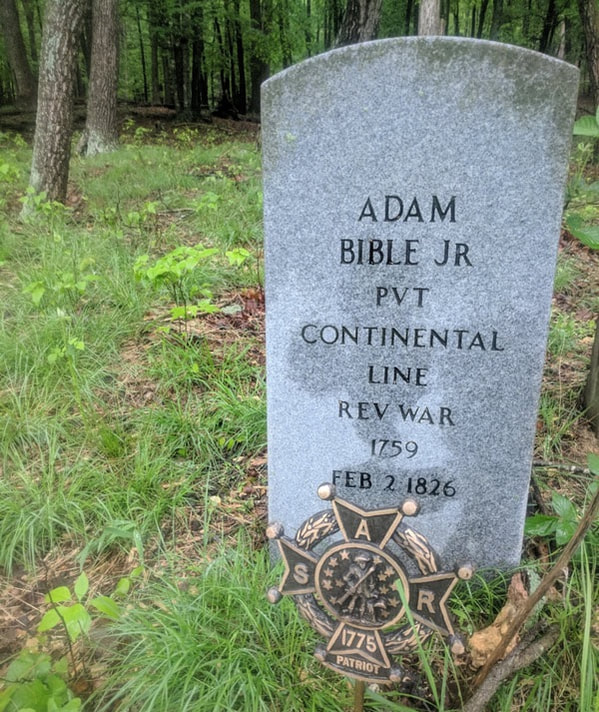

| Pvt. Adam Bible came from a German family that lived at Henckel's Fort in Germany Valley, now in Pendleton County, West Virginia. He was recruited by Lt. John Gratton and enlisted in Capt. David Stephenson's company in February of 1776. He was discharged from Valley Forge in February 1778. He moved to Rockingham County and married Magdalene Shoemaker in 1783. He died in 1826 and is buried Fulks Run. |

| Gen. Benjamin Biggs was a veteran of Lord Dunmore's War when he enlisted in John Stephenson's independent company in 1775 for one year of service. He served in the 13th Virginia Regiment to the end of the war, rising from lieutenant to captain. He settled in Ohio County (now West Virginia) and married Priscilla Metcalf. He was one of the founders of the town of West Liberty. He served in the Virginia House of Delegates in the 1790s and as a general in the Virginia militia from 1794 through the War of 1812. He died in 1823. He is buried in West Liberty. |

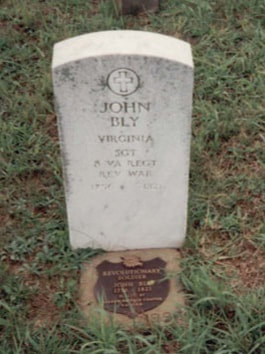

| Sgt. John Bly was born in Pennsylvania in 1756 and moved to the Shenandoah Valley as a child. He was a carpenter who enlisted in Capt. Jonathan Clark's company on February 5, 1776. He was detached with Captain Croghan for the 1776 campaign and was probably at White Plaints and Trenton and possibly at Assunpink Creek and Princeton He was promoted to sergeant and discharged in 1778. He returned to Shenandoah County after served there as a lieutenant in the militia. He died in Shenandoah County in 1821. He is buried in Boehm Cemetery. His original fieldstone marker was replaced with a government veteran's marker in 1968. |

| Col. Abraham Bowman was born near Strasburg, Virginia in 1748. He was an early long hunter and then appointed lieutenant colonel of the 8th Virginia late in 1775. He was promoted to colonel in 1777 and was released as supernumerary in 1778. He lead a group of settlers to Kentucky in 1779, living for a time at Bowman's Station near Harrodsburg. He established Cedar Hall plantation near Lexington in the 1780s and lived there until his death in 1837. He greeted Lafayette in Lexington during the general's tour of America in 1825. |

| Gen. Robert Breckenridge was born in Augusta County in 1754 and was an apprentice carpenter when he enlisted as a sergeant in Capt. James Knox's company in 1776. He received an ensign's commission in 1777 and was a 1st lieutenant when he was taken prisoner at the surrender of Charleston in 1780. He was exchanged and served as adjutant of the Virginia Battalion until 1783. He represented Jefferson County (now Kentucky) at Virginia's constitutional ratification convention in 1788 and as the first speaker of the Kentucky House in 1792. He was appointed a brigadier general in the Kentucky militia in 1792 a major general in 1794. he never married and died in 1833. He is buried in the Floyd-Breckenridge Cemetery in Louisville, Kentucky. |

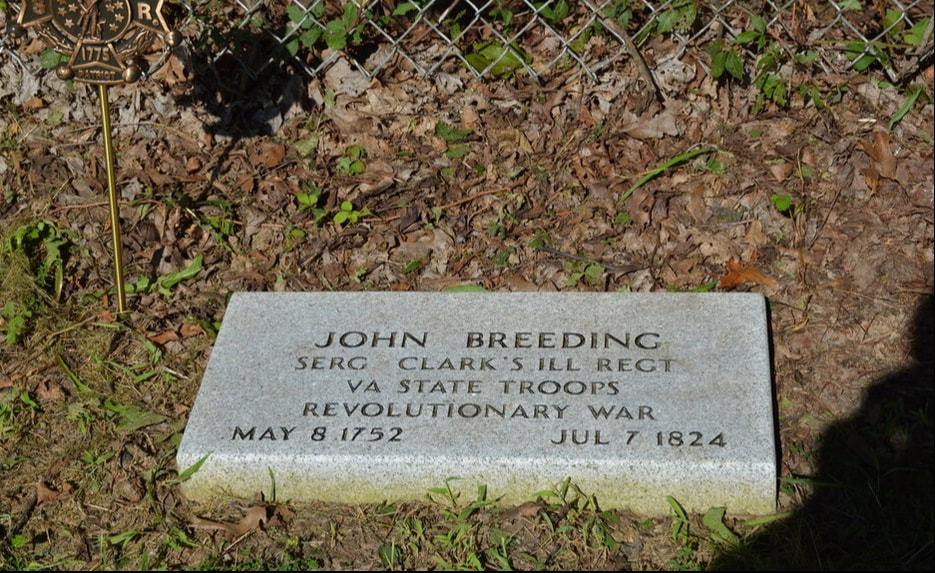

| Pvt. John Breeding was born in 1752 and enlisted in Capt. Jonathan Clark's company in February 1776. He deserted, but appears to be the same John Breeding who then served in George Rogers Clark's Illinois Regiment from 1779-1780. He married Elizabeth Napper in 1785 and moved to Missouri by 1818, where he died. He is buried in Franklin County, Missouri. |

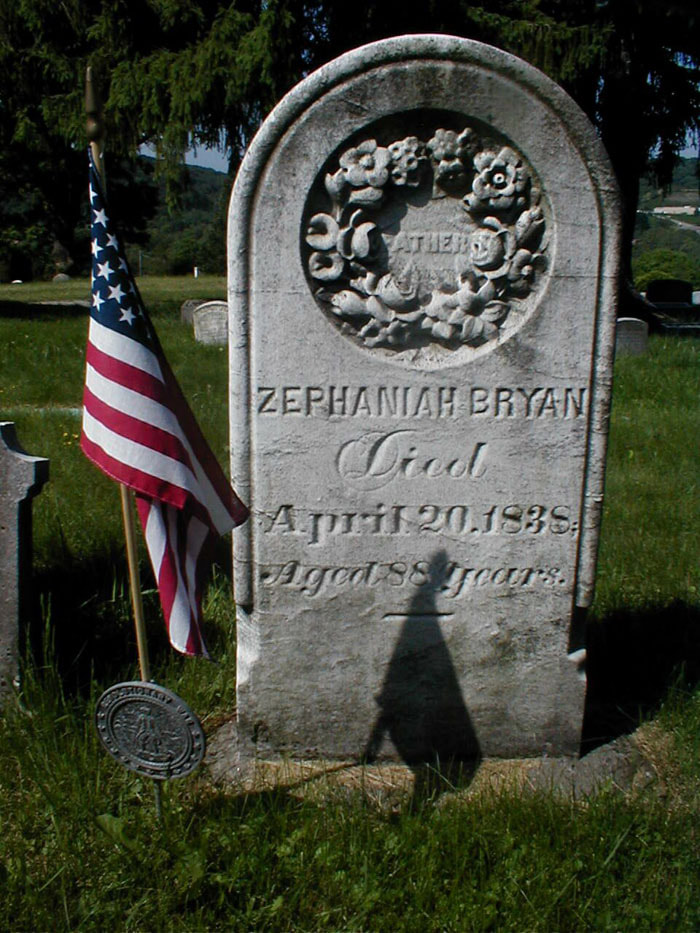

| Pvt. Zephaniah Bryan, known as "Seth," was born in Maryland about 1752 and enlisted in Capt. John Stephenson's one-year West Augusta District company in 1775. He was married twice, to Elizabeth DeVeiuz and to Jane McLane. He lived in Allegheny and Westmoreland counties in Pennsylvania. He died in 1838 and is buried in Murrysville Cemetery in Westmoreland County. There is no surviving roster of Stephenson's company and only a few members have been identified by other means. Bryan's is the only known grave of an enlisted man from Stephenson's company. |

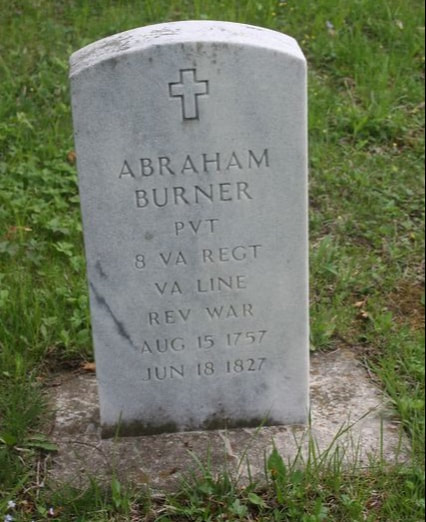

| Pvt. Abraham Burner enlisted in Capt. Matthias Hite's company at Woodstock in December of 1776 and served through his discharge in January, 1779. Hite commanded after Richard Campbell was promoted to major. Burner appears to be the brother of Daniel Burner who enlisted early in 1776. Abraham served an extended militia tour in South Carolina in 1780 with 8th Virginia veteran Capt. Jacob Rinker in South Carolina under Gen. Nathanael Greene. They were at Cheraw Hills at the time of the Battle of Cowpens and escorted prisoners from that battle to Virginia. He later lived in Pendleton County, now West Virginia, where he died in 1819. He is buried in Bartow, Pocahontas County. |

| Sgt. Robert Chambers was born in London, England in 1756. He enlisted in Capt. Robert Higgins' company in Augusta County in August 1777. He was detached to fight at the defense of Fort Mifflin that fall and served under 8th Virginia veterans Capt. William Croghan and Capt.-Lieut. Leonard Cooper after the regiment was folded into the 4th Virginia Regiment. He was promoted to corporal and then lieutenant. He was taken prisoner with the Virginia Line at the surrender of Charleston in 1780. He lived until 1836 and is buried in Monroe County, West Virginia. |

| Pvt. John Chenoweth was born on the frontier in 1755 and enlisted in Capt. Abel Westfall's company in February 1776. He was captured at the Battle of Germantown and exchanged in 1778. He married Mary Pugh in 1779 and served in the militia during the Yorktown campaign of 1781. He died in 1781 in Randolph County, now West Virginia. He is buried in Daniel's Graveyard in Elkins, West Virginia. |

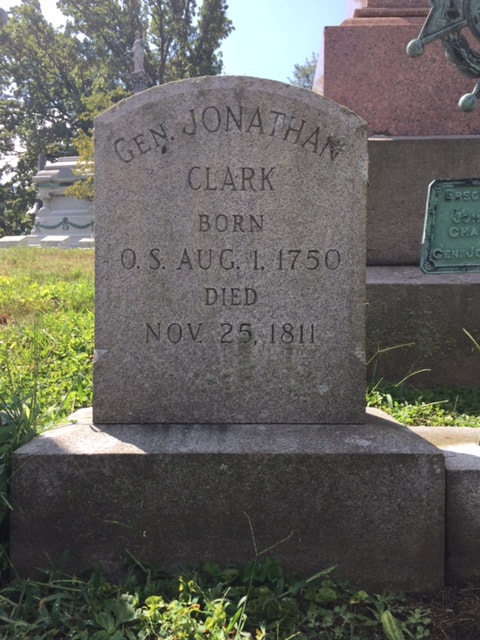

| Maj. Gen. Jonathan Clark was born August 1, 1750 (Julian Calendar) in Albemarle County. His family moved to Caroline County to avoid the violence of the French & Indian War. He served in the Dunmore Volunteer Company in 1775 and was appointed an 8th Virginia company captain in 1776. He was the regiment's last major before it was folded into the 4th Virginia in 1778. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel and played an important role in the Battle of Paulus Hook in 1779. He was taken prisoner at Charleston in 1780. He was appointed a Virginia bounty land commissioner in 1783. He was appointed a major general in the Virginia militia in 1792. He later moved to Kentucky where his parents and siblings had settled. He was the older brother of Gen. George Rogers Clark and explorer William Clark. He married Sarah Hite. He died in 1811 and is buried Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville. |

| Pvt. William Clark was born in Pennsylvania and moved to Hampshire county at age 10. He was drafted into Capt. Jonathan Clark's Company in 1778 for one year. He was in Capt. Abraham Kirkpatrick's company after the regiment was folded into the 4th Virginia Regiment and then discharged in January. He served in a militia unit during the Yorktown campaign. He married Barbara Hemlock in 1798 and lived in Randolph and Lewis counties, now West Virginia. He died in 1841 and is buried in Upshur County. It is unlikely that he was related to Captain Clark. |

| Pvt. Daniel Cloud was born in 1755 and enlisted in Capt. Richard Campbell's company in June 1776, after the regiment had left for the south. He was detached with Capt. William Croghan to the 1st Virginia Regiment and the northern army, likely serving at White Plains and Trenton and possibly Assunpink Creek and Princeton. The name of his first wife is not known. His second wife was Elizabeth Hampton. He died in 1815 and was buried at Willow Glen (probably a farm). his grave was relocated to Prospect Hill Cemetery in Front Royal, Virginia. |

| Pvt. Harmon Commins enlisted in Capt. William Croghan's company at Sharpsburg, Maryland at the age of twenty. He fought at White Plains, Trenton, and Princeton. He was wounded in the leg and captured at the Battle of Germantown, but exchanged in 1778 after his enlistment had expired. He married Mary James in 1779 and moved to South Carolina some time before 1819, residing first in the Pendleton District (county) and then in Anderson District (county), where he is buried. His modern marker erroneously says he was "VA militia." |

| Capt. James Craig was born in 1744 and served first in the Southwest Virginia Independent Company in 1775. In 1776 he was appointed ensign in Capt. James Knox's company. He was detached with Knox to Morgan's Rifle Battalion in 1777. He was promoted to captain and then retired as a supernumerary officer in 1778. He was deputy sheriff of Washington County in 1782. He married three times. He was an original justice of the peace of Muhlenberg County, Kentucky in 1799. He died in 1816 and is buried in Rosewood, Kentucky. (KY SAR) |

| Maj. William Croghan was born in Ireland in 1752 and may have come to America as a British soldier. He was appointed a captain by the West Augusta (Pittsburgh) Committee of Safety in 1776 and led a detachment of the 8th Virginia to the 1st Virginia Regiment and the northern army. He served as brigade inspector and was then promoted to major in 1778. He was taken prisoner at the surrender of Charleston in 1780. He was present for the surrender at Yorktown but unable to participate because he was on parole. He served until 1783. He married Lucy Clark, the sister of Capt. Jonathan Clark. He moved to Kentucky where he administered distribution of bounty land to veterans. He died in 1822 at his estate, Locust Grove. His grave was relocated to Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville. |

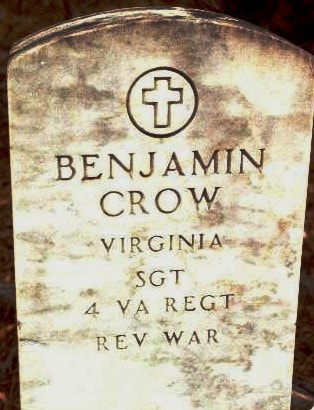

| Sgt. Benjamin Crow was born in 1756 or 1757 in New Castle County, Delaware, and moved to the frontier as a child. He was the brother of Pvt. Jacob Crow. He enlisted as a corporal in Capt. David Stephenson's Augusta County company late in 1776 and was promoted to sergeant in 1777. He served in Major Croghan's company after the 8th Virginia was folded into the 4th Virginia Regiment. He was discharged in 1779 and married Ann Gragg. He moved to the Nolichucky settlement, now in East Tennessee, in 1782. He later moved to Upper Spanish Louisiana (now Missouri) and then to the Arkansas Territory where he died in 1830. He is buried in Clark County, Arkansas. |

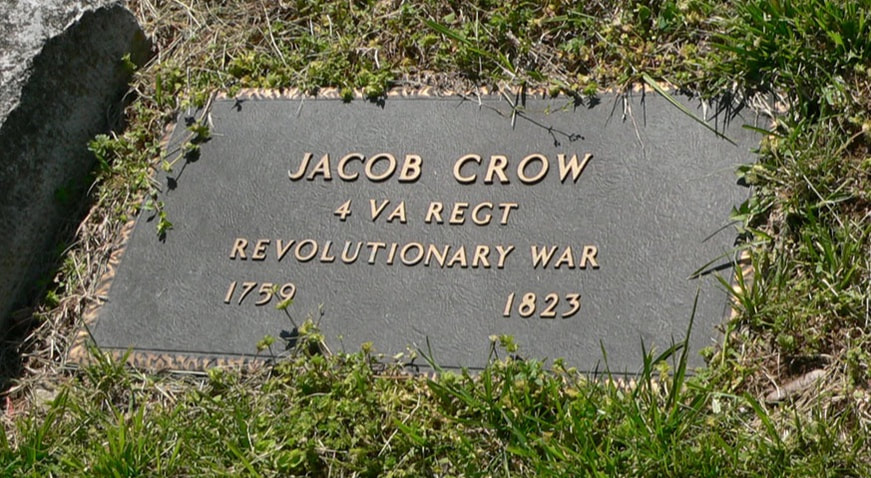

| Pvt. Jacob Crow was born in 1759 and joined in Capt. David Stephenson's company in February 1778. He may have been drafted. He was the brother of Sgt. Benjamin Crow. He was discharged in February 1779 and married Eleanor Right in 1787 in Lincoln County, Kentucky. He died in 1823 and is buried in Boyle County, Kentucky. |

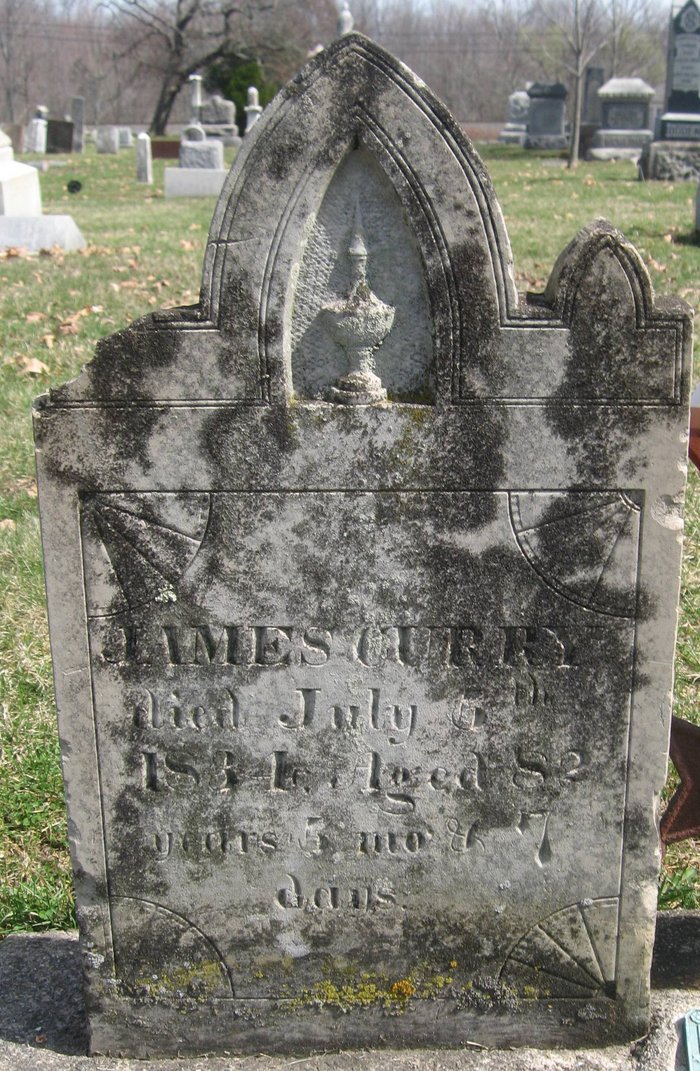

| Col. James Curry was born in Ireland in 1752. He served in Captain Moffett's Company in Dunmore's War and was wounded in the right arm at the Battle of Point Pleasant. He received an 2nd lieutenant's commission in June, 1777 in Capt. Robert Higgins' new company for the 8th Virginia. He was promoted to 1st lieutenant under Capt. Abraham Kirkpatrick in the 4th Virginia after that regiment absorbed the 8th Virginia. He was promoted to captain in 1779 and was taken prisoner at the surrender of Charleston in 1780. He was paroled to the end of the war. He married Mary Magdalene Burns and resided in Madison County, Ohio by 1815 and in Union County, Ohio by 1828. He died in 1834 and is buried in Oakdale Cemetery. A plaque referring to him as "Col.James Curry" appears to be based on a rank he achieved in post-Revolutionary militia service. |

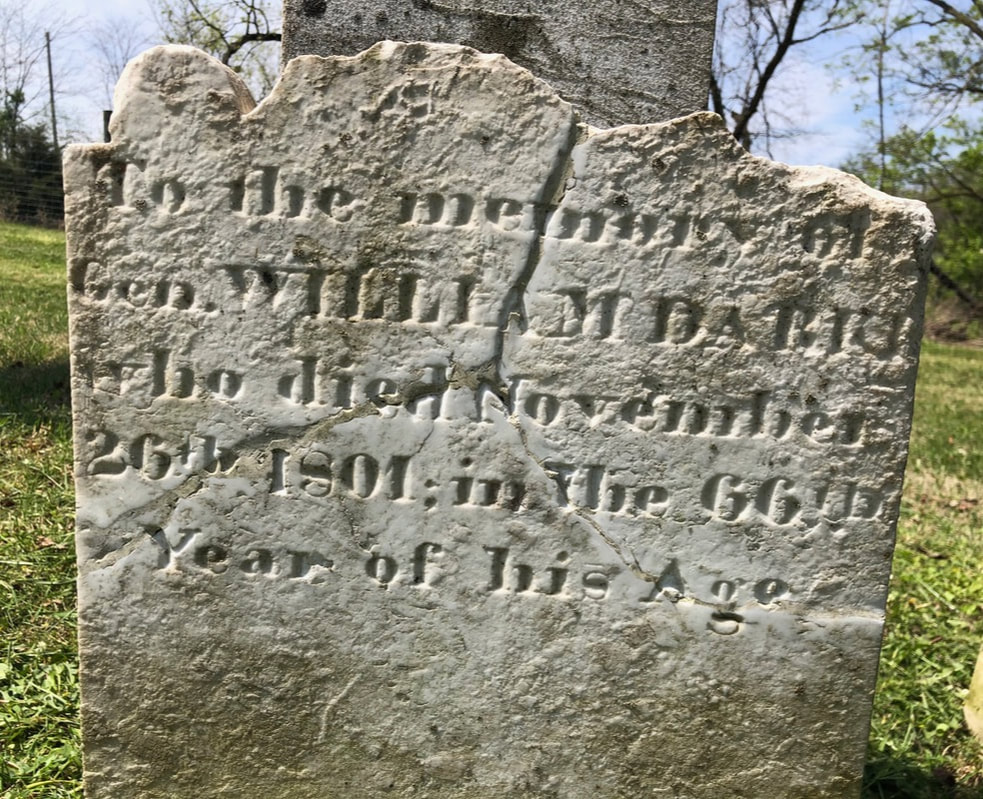

| Brig. Gen. William Darke was born in Pennsylvania in 1736. He served in the French & Indian War. As a captain, he raised a company from Berkeley County and was promoted to major in 1777. He was captured at Germantown, promoted to lieutenant colonel while in captivity, and exchanged in 1780. Though a Continental officer, he led militia at Yorktown. He commanded a regiment in the St. Clair Expedition of 1791. He helped suppress the Whiskey Rebellion as a general of militia. A founder of Jefferson County, he died in 1801. |

| Joseph Dean was enlisted by Ens. Henry Field on April 27, 1777 into George Slaughter's company. He was sick through the summer and fall and probably missed the engagements at Brandywine and Germantown. Dean's company was later commanded by Capt. Abraham Kirkpatrick. He remained with Kirkpatrick's through Monmouth and the regiment's merger into the 4th Virginia in 1778. He was probably taken prisoner at Charleston in 1780. He is buried in Presbyterian Cemetery, Alexandria, Virginia. |

| Pvt. William Eagle enlisted late in 1777 to serve in Capt. John Steed's company (previously commanded by Capt.Richard Campbell and briefly by Capt. Matthias Hite). He was apparently sixteen years old at his enlistment. After the regiment was folded into the 4th Virginia he served under Capt. Abraham Kirkpatrick. He was discharged in 1779 before his enlistment expired, possibly because of ill health or injury. He is buried in Smoke Hole Canyon in Pendleton County, West Virginia, facing Eagle Rocks, a geological formation named for him. |

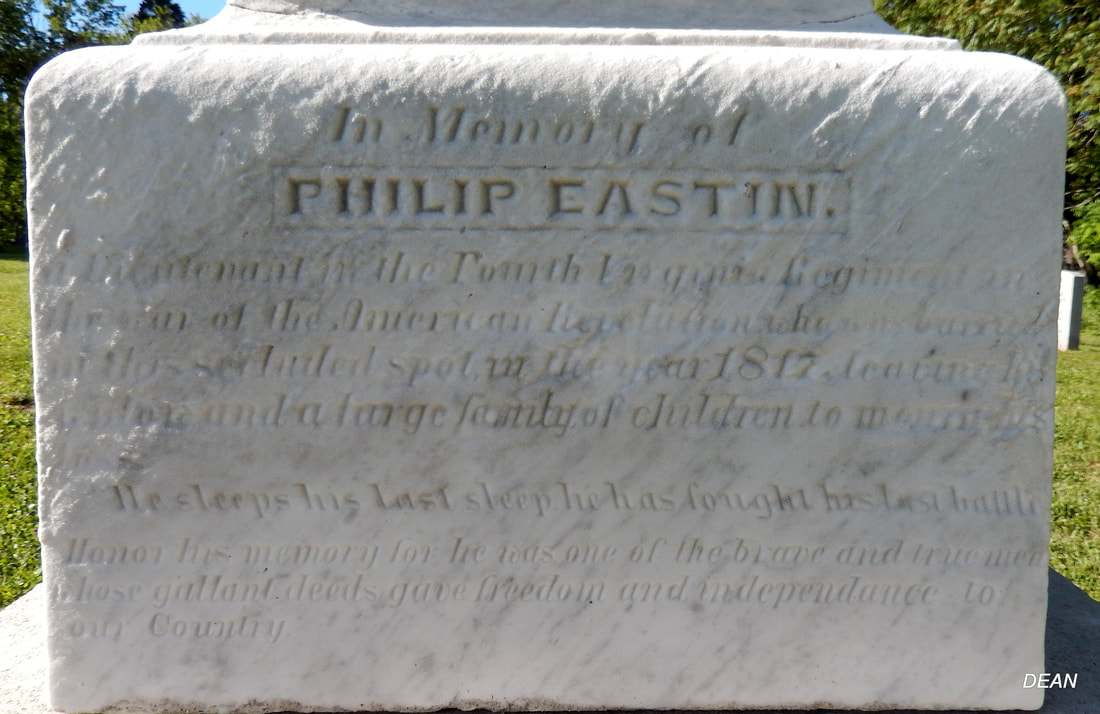

| The grave of Lt. Philip Eastin in Jefferson Co., Ind. Eastin enlisted in 1776 as a private, earned an officer's commission in Jonathan Clark's company. He served to the end of the war and moved west, where he died in 1817. His monument says, “He sleeps his last sleep, he has fought his last battle. Honor his memory for he was one of the brave and true men whose gallant deeds gave freedom and independence to our Country.” |

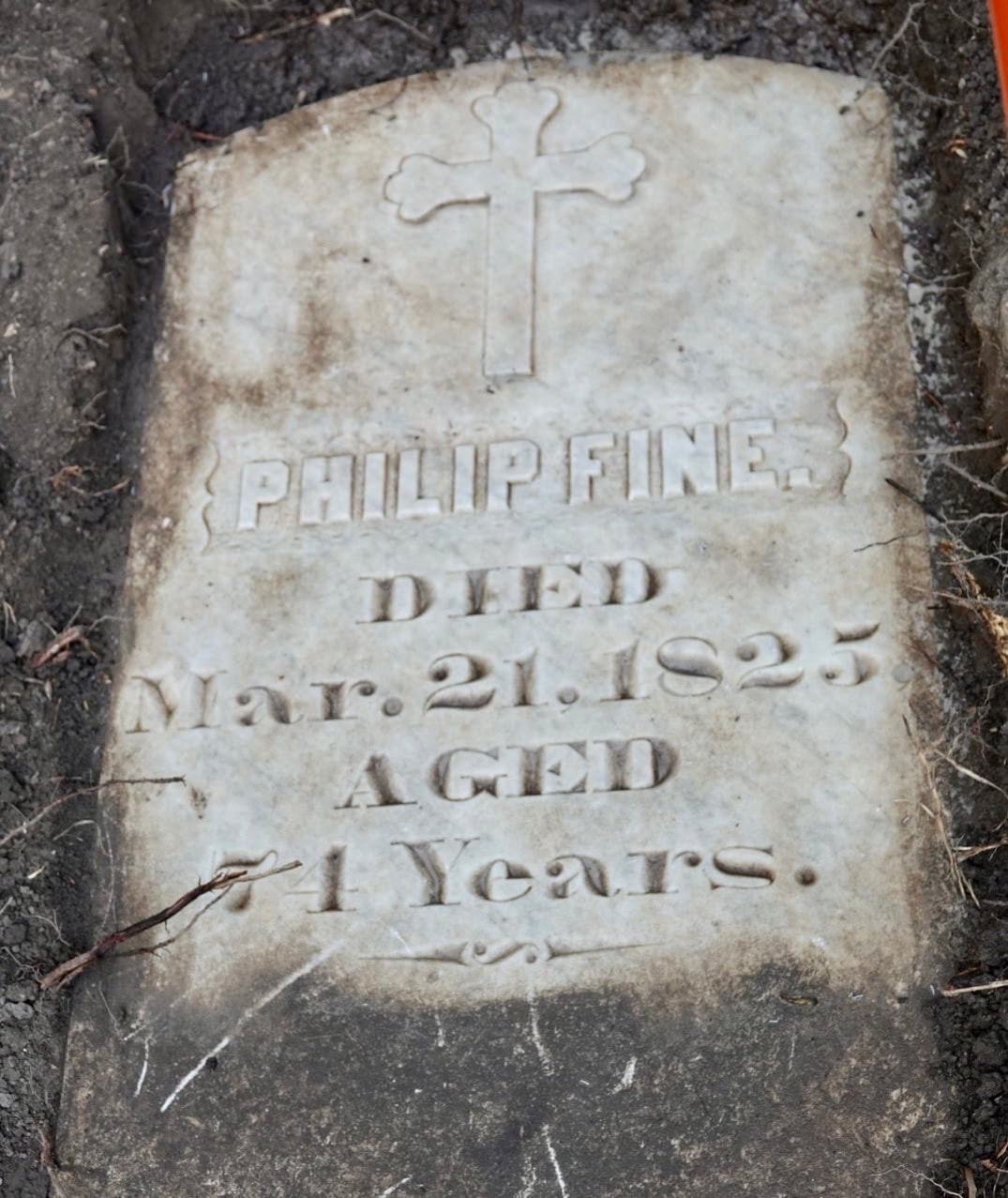

| Cpl. Philip Fine was born in Virginia in 1751. He enlisted in Capt. Jonathan Clark's company with his brother Andrew in February 1776. Their brother Thomas joined the following year and Andrew died in service. Philip married Sarah Celeste Boly and moved to St. Louis in 1781, more than two decades before the Louisiana Purchase. For many years he ran a ferry across the Meramac River near its mouth south of St. Louis. He died there in 1825. His gravestone was found in 2021 nicely preserved under the soil of property now owned by Ameren Power in southern St. Louis County. The nearest road is "Fine Road." |

| Cpl. Joseph Golladay enlisted as a private in Capt. Jonathan Clark's company early in 1777. He was promoted to corporal on October 1. He was engaged at the battles of Brandywine, Germantown, and Monmouth. After the regiment was folded into the 4th Virginia Regiment, he served in Capt. Abraham Kirkpatrick's company. His three-year term expired early in 1780, shortly before most of the Virginia line was taken prisoner at the surrender of Charleston. He returned to Shenandoah County and married Mary Huslender. He died in 1826. |

| Pvt. Jonathan Grant was born in 1755 and enlisted in Capt. William Croghan's company at Fort Pitt (Pittsburgh) in February of 1776. After marching to Williamsburg, he went with Croghan's detachment north to join Washington's army. He fought at the battles of Mamaroneck, White Plains, Trenton, Assunpink Creek, and Princeton. He carried Lt. Abraham Kirkpatrick from the battlefield at Princeton. He was detached to Gen. William Maxwell's Light Infantry in August of 1777 and fought with that unit at Cooch's Bridge and Brandywine. He was wounded at Germantown and discharged after the encampment at Valley Forge. He returned to Pittsburgh and served as a scout during the Northwest Indian War. He later settled in Wayne (now Holmes) County, Ohio, where he died in 1833. |

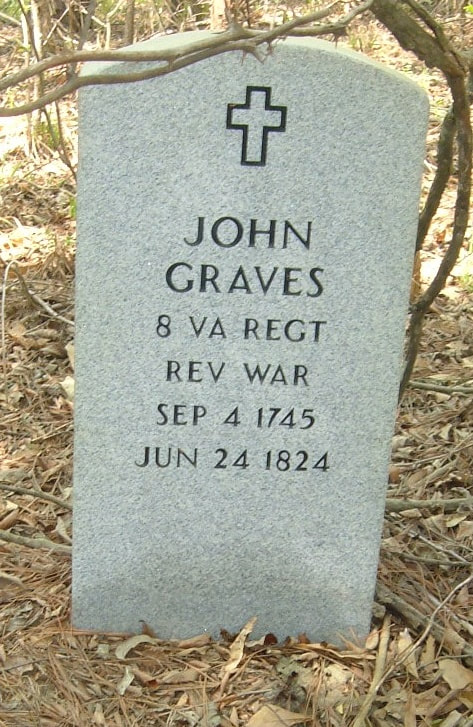

| Capt. John Graves was born in 1745 and signed on as an ensign in Capt. George Slaughter's company in February 1776. He was promoted to lieutenant that October. He briefly took command of the company after Captain Slaughter's resignation in December, 1777. Graves then resigned from the army in April, 1778. He moved to Georgia, living near namesake Graves Mountain in Lincoln County and then French Mills in Wilkes County. He died in 1824 and is buried in the family cemetery. |

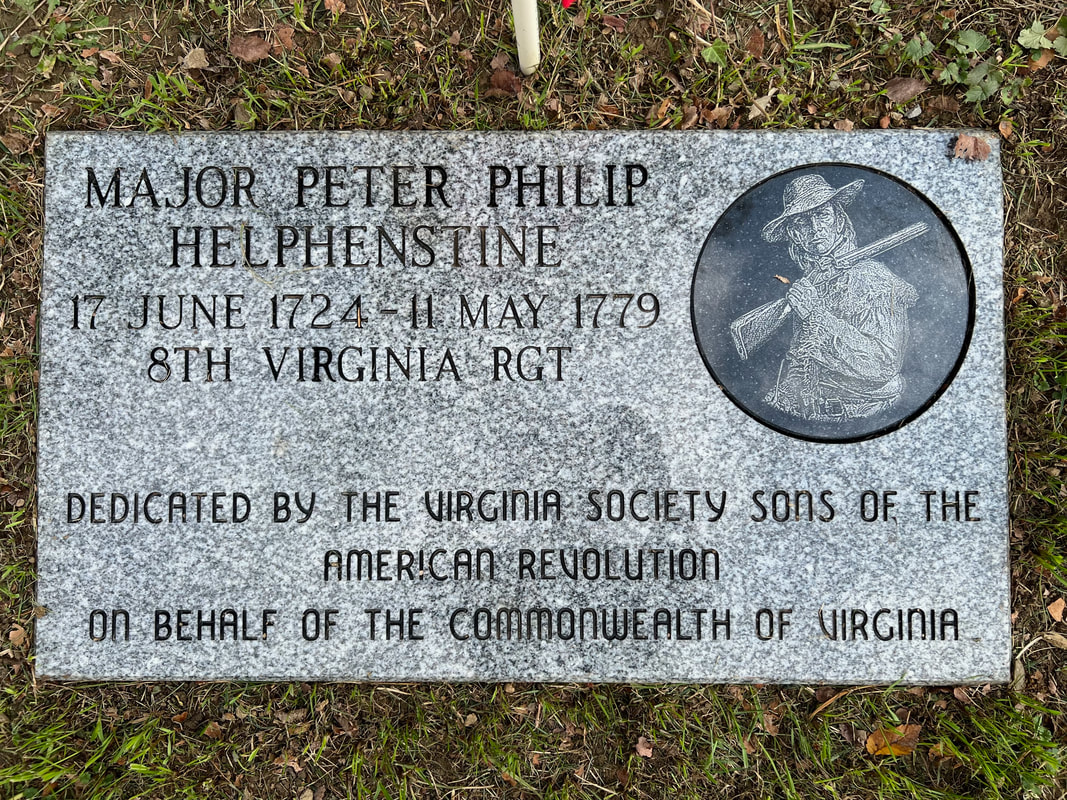

| Maj. Peter Helphenstine, one of the regiment's three original field officers, immigrated from Germany in 1754. He prospered in Winchester and was commissioned to help lead the "German Regiment" in December 1775. He contracted malaria in South Carolina in 1776, resigned, and died at home of complications of the disease in 1779. His wife was left destitute and he may never have had a permanent marker until the SAR dedicated one in November, 2022. His exact burial site at Mt. Hebron Cemetery is not known. |

| Sergeant "Big Dan" Hendricks, who was remembered to be 7 feet tall, was born in York County, Pennsylvania before setting his family in what is now Jefferson County, West Virginia. He was an active combatant in a pre-war feud between Jacob Hite and Sheriff Adam Stephen. He joined William Darke's company early in the war. When the 8th Virginia was assigned to Maj. Gen. Adam Stephens' division in 1777, Hendricks left the regiment with no explanation recorded on the rolls. He is buried in the Buckles-Hendricks-Oborne Cemetery in Jefferson County. |

| Lieut. Peter Higgins was born in 1755, probably in present Hardy County, West Virginia in the 1750s. He signed on as an ensign in the new company formed by his younger brother, Capt. Robert Higgins, in 1777. He was promoted to 2nd lieutenant in the fall and to 1st lieutenant in the 4th Virginia Regiment in 1779. He was in Gen. Nathanael Greene's southern army later in the war and continued on until the end of the Revolution. His second wife was the daughter of 8th Va. Lt. Taverner Beale. He died in 1808 and is buried in Saint Matthews Cemetery in New Market, Shenandoah County. (Updated and corrected 1/27/24.) |

| Capt. Robert Higgins was born in Pennsylvania in 1746. His family settled in what is now Hardy County, West Virginia. when he was a child. He experienced the French and Indian War first hand, narrowly escaping from Indians when he was twelve. He married Sarah Wright in about 1766. He was appointed a lieutenant in Capt. Abel Westfall's company early in 1776 and was selected by General Washington to raise a new company to replace John Stephenson's one-year men in 1777. He was captured at the Battle of Germantown and held for about nine months before being paroled. He returned to service until the end of the war. His wife died during the war and his farm and children were capably cared for by slave known as "Old Jack." He built a home after the war in Moorefield, West Virginia which survives. In 1797 he married Mary Jolliffe, the widow of 8th Virginia lieutenant John Jolliffe who had died of smallpox. He moved briefly to Kentucky and then to what is now Higginsport, Ohio, fronting the Ohio River. He died there in 1825. |

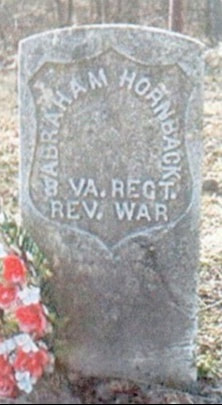

| Pvt. Abraham Hornback enlisted in Capt. Abel Westfall's Hampshire County company early in 1776. He was picked to serve in Morgan's Rifles in 1777 and was likely at the surrender of Burgoyne at Saratoga. He was discharged at Valley Forge in 1778. There are two alleged gravesites for him in Medford County, Illinois and in Spencer County, Indiana. (Findagrave.com) |

| Quartermaster Sgt. Arthur Johnson enlisted in James Knox's Fincastle County company in 1776 and later reenlisted into Capt. Berry's company. Later in this enlistment he was commanded by Capt. Croghan. His unusually elaborate monument near Enfield, Illinois is not original and credits him with service at Norfolk and Paoli he could not have participated in though other details are correct. |

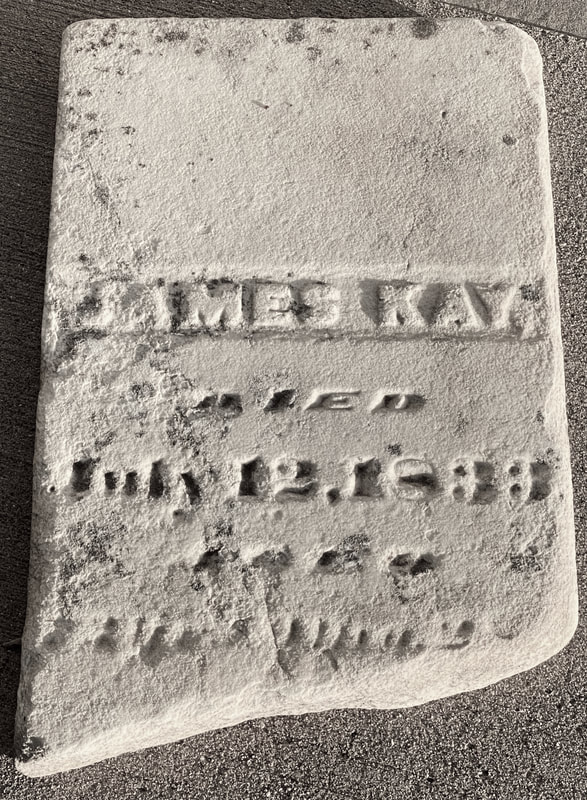

| Pvt. James Kay enlisted in Capt. Thomas Berry's company on February 20, 1776. He was "badly" wounded at Brandywine in 1777 and moved to Kentucky after the war. He died in 1833 and is buried at Salem United Baptist Church in Boone County. His worn and broken headstone was replaced in a joint effort by the Sons and Daughters of the Revolution in 2022. |

| Maj. Abraham Kirkpatrick was born in Maryland in 1749. He moved to the Pittsburgh in 1767 and was appointed a lieutenant in Captain Croghan's company in 1776. He led Croghan's detachedment under Washington at Trenton, Assunpink Creek, and Princeton. He served as adjutant and was promoted to captain and then major before the 8th was folded into the 4th Virginia. He remained in service to the end of the war. He married Mary Anne Oldham in 1786 and died in 1817. He lies in Allegheny Cemetery in Pittsburgh. |

| Lt. Col. James Knox was probably born in Augusta County. A tradition that he immigrated alone from Ireland as a boy appears to be inaccurate. He was an early Kentucky long hunter and a scout for Col. Andrew Lewis in Dunmore's War. He was a lieutenant in Capt. William Russell's Southwest Independent Frontier Company in 1775. He was appointed a captain by the Fincastle County Committee of Safety in 1776 to raise a company assigned to the 8th Virginia. He was at Charleston in 1776 and detached to lead a company in Daniel Morgan's Rifle Battalion in 1777, serving in the Saratoga campaign. He was probably at Monmouth in 1778 and then released as a supernumerary officer when regiments were consolidated. Gov. Thomas Jefferson appointed him to lead one of two Virginia frontier battalion. He led parties of settlers into Kentucky after the war and served in the Virginia House of Delegates and the Kentucky Senate. He married Ann Montgomery, the widow of his friend Benjamin Logan in 1805. He died 1822 and is buried in Shelby County, Kentucky. |

| Sgt. James Lamb was born in 1756 in Scotland. He enlisted in Capt. David Stephenson's company in March, 1776. He married Hannah Boone, first cousin of Daniel Boone. He moved to Bourbon County, Kentucky after the war. and then to Wayne County, Indiana. In 1812 he left Kentucky and moved to Wayne County, Indiana because of his strong anti-slavery views. He died after falling from a horse in 1741 and is buried in Elkhorn Cemetery near Richmond, Indiana. His house in Wayne County is still standing. |

| Fife Major William Lipscomb, Jr. was in Louisa County in 1756. His father was a member of the Louisa County Committee of Safety. He was appointed fife major in February 1778, a few months before the regiment folded into the 4th Virginia. He continued on until at least April 1779. He moved with his family to South Carolina and died there in 1802. He is buried in the Lipscomb Family Cemetery in Cherokee County. |

| A memorial to William Lewis Lovely is surrounded by campsites in Lake Dardanelle State Park, near Russellville, Arkansas. Lovely was a lieutenant in Capt. James Knox's company and followed Knox into Morgan's Rifles. Lovely rose to captain, but not while with Morgan. He was a federal Indian agent after the war, best known for brokering peace between the Cherokee and Osage tribes. The location of this marker near the shore of a manmade lake suggests it may be a cenotaph. |

| Martin Maney was born in County Wexford, Ireland in 1752. He served in Capt. James Knox's company. His pension states that he enlisted on about December 4, 1775 at the Long Island of the Holston River (now Tennessee). This was before Knox or his subaltern officers were appointed and may indicate that he first served in William Russell's Southwest Frontier Independent Company and left that unit with Knox to form the new company. He deserted on June 7, 1776, possibly in protest of the still-provincial regiment leaving Virginia for the Carolinas. He enlisted again in the 9th Virginia Regiment. He married Keziah Vann in 1781. He performed active militia service under John Sevier in 1780 and 1782 and performed scout service. He lived in Blount County, Tennessee and Buncombe County, North Carolina. He died in 1830. |

| Thomas Miller, a native of Maryland, signed on as an ensign in Captain Darke's company in 1777. He rose to 2nd lieutenant and was briefly believed to have been captured at Germantown. Later in the war, he was at the battles of Cowpens and Guilford Courthouse. He was unable to drop the bad habits he developed during the war, abandoning his family and struggling with alcoholism. He is buried in the Patriot Square section of Grandview Cemetery in Chillicothe, Ohio. |

| Lieut. Christopher Moyers (also "Myer" and "Moyer") was born in Culpeper, Virginia in 1740. He was made an ensign in Capt. William Darke's company in August of 1776. The regiment was in South Carolina at this time, suggesting he was promoted from the ranks. He rose to 2nd lieutenant in May 1777 and was captured at the Battle of Germantown on October 4. He and Ens. Philip Huffman escaped in June of 1778 and returned to service. Moyers was promoted to 1st lieutenant and served another year, resigning in March 1779. His wife's name was Susannah. He moved to Jefferson County, Tennessee, where he was one of the first settlers of White Pine. He died in 1815, and is buried in the "Old Christopher Moyers Graveyard in White Pine. His government-issue headstone identifies him as a lieutenant of the 4th Virginia Regiment, which is accurate for his last few months of service. |

| Maj. Gen. Peter Muhlenberg was born in Trappe, Pennsylvania in 1746. He was the son of Henry Muhlenberg, the patriarch of the Lutheran Church in the America and the grandson (on his mother's side) of Conrad Weiser, an important early Indian trader and diplomat. He served briefly in the British 60th Regiment in the 1760s. He married Anna Barbara Meyer in 1770. He was ordained by his father and then ordained in the Church of England to lead a parish in the Shenandoah Valley. He served in the revolutionary Virginia Convention, received a colonel's commission in 1775 and was promoted to general in 1777. He played an important role in the Yorktown campaign and received a brevet promotion to major general at the end of the war. He returned to Pennsylvania and served as Vice President of that state and in the U.S. House and Senate. He died in 1807 and is buried in Trappe. |

| Lieut. Jacob Parrot was born about 1744. His parents lived in a cabin at the headwaters of Jordan Run in what is now Shenandoah County. They were probably from Switzerland. They were among the very earliest settlers of the Shenandoah Valley, acquiring their land from Jost Hite in the North Mountain settlement near the future sites of Woodstock and Toms Brooks. He inherited their house and was living there in 1786. He was commissioned an ensign in Capt. Jonathan Clark's company in March 1776 and promoted to 2nd lieutenant a year later. He was cashiered that May for being away without leave. He died in May of 1829 and is buried in St. John Lutheran Cemetery in Singers Glen, Rockingham County. Since this photo was taken in 2013 his marker has broken and is in urgent need of attention. He was the brother of Joseph Parrot. |

| Capt. Joseph Parrett was born in what is now Shenandoah County, Virginia in 1760. He enlisted in Capt. Jonathan Clark's company two months before his sixteenth birthday in February 1776. He was promoted to sergeant in 1777 and may have been briefly detached to Morgan's Rifle Battalion. He was discharged at Valley Forge in January, 1778. He served as ensign of a Shenandoah County militia company in 1779 and as a lieutenant in 1781. He was referred to late in life as "captain," probably referring to further militia service. He married Anna Maria Wendel in 1780 and moved to Fayette County, Ohio about 1812. He married Anna Hartman in 1837 and died in 1847. He is burial site was reportedly obliterated by development, but there is a memorial stone for him in nearby Sugar Grove Cemetery in Clinton County, Ohio. |

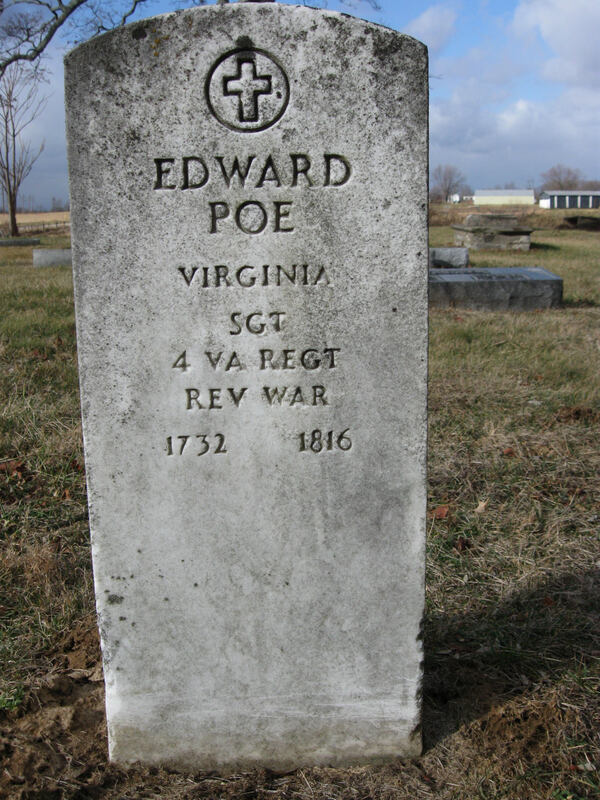

| Cpl. Edward Poe enlisted in Capt. William Darke's company early in 1776 and was promoted at some point to corporal. He reenlisted in December and was listed once (possibly in error) as a sergeant. He was detached to the artillery in 1777 and was assigned to Captain Croghan's company after the regiment was folded into the 4th Virginia. He was probably taken prisoner at Charleston in 1780. Poe was born in 1732, making him twenty years older than the average enlisted man. He was born in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. He married Martha Britain in 1753 and was remarried about 1776 to Catherine Edward. He lived in Baltimore County, Maryland for a few years after the war and then moved to Bracken County, Kentucky in 1797. He died there in 1816. He is buried in Sharon Cemetery next to Catherine. (Mike Smith) |

| James Range was born in Somerset County, New Jersey in 1754. He enlisted in Capt. William Darke's company early in 1776 and was captured by the enemy on October 1, 1777--three days before the Battle of Germantown. His two year enlistment expired while he was in captivity and was liberated in an exchange of prisoners in August, 1778. He explored the Warpath River in what is now middle Tennessee in 1779 and may have served militia duty under Gen. Edward Stevens during the Yorktown campaign. He married Barbara Hammer in 1787 in Washington County, North Carolina (now Tennessee. He died in 1825 in Carter County, Tennessee. His gravestone is improperly marked "8th Va. Mil[itia]." |

| | Col. Jacob Rinker, Jr. was born in what is now Shenandoah County, Virginia to Swiss immigrants in 1749. He was appointed a lieutenant under Capt. Jonathan Clark in March 1776. He resigned his Continental commission after about fourteen months, but led a militia company under Gen. Nathanael Greene in 1780. He may also have served under Gen. George Rogers Clark in the Illinois Regiment. He married twice, voted to ratify the U.S. Constitution, and served several years in the Virginia House of Delegates. He died in 1827 and is buried near his father in a beautiful hilltop cemetery in western Shenandoah County. His lifelong home, built by is father, still stands nearby. |

| Ashkenaz Shappee, usually recored as "Askin Shippy," served as quartermaster sergeant from June 3, 177 until about April of 1778. Genealogies state he was born in Lorraine, France in 1749 and may have belonged to a a Huguenot family. He died in New York in 1797 and is buried in Beaver Dams in the northwest corner of Chemung County, |

| Jacob Sivley was born in what is now Shenandoah County and drafted into Capt. Jonathan Clark's company in February 1778. He was put in Capt. Abraham Kirkpatrick's company of the temporarily combined "4th-8th-12th Virginia Regiment" and stayed with Kirkpatrick when the 8th Virginia was folded into the 4th Virginia in the fall of 1778. He was discharge in February 1779. He moved to Tennessee before 1808 and then settled on Indian Creek, south of Huntsville, Alabama. He married a widow named "Alcey" or "Alice" (possible Alice). He died in September 1816 and is buried Huntsville. |

| Col. John Stephenson was born in Frederick County, Virginia in 1736. He served in Dunmore's War and may have served in the French & Indian War. He settled near what is now Connellsville, Pennsylvania in 1768. In 1775, he was made captain of the second West Augusta independent frontier company, which was later assigned to the 8th Virginia. He was a colonel of Yohogania County militia in 1778, leading men in the Squaw Campaign and the McIntosh Expedition. He moved to what is now Harrison County, Kentucky about 1790. He married a woman named Mary, but they had no children. He died in 1801 and was buried near his home, which is still standing. His roughly-made gravestone was stolen in the 1980s but recently reappeared. |

| Chaplain Christian Streit was born in Pennsylvania in 1749 to Swiss immigrants. He studied theology under Henry Muhlenberg, father of 8th Virginia Col. Peter Muhlenberg and was ordained in 1770. He was recommended as a chaplain by Henry Muhlenberg in 1776 and is recognized as the first denominationally-sponsored army chaplain in American history. He joined the regiment in 1777 was later chaplain of the 9th Virginia Regiment. He was taken prisoner at the fall of Charleston in 1780. He preached in Pennsylvania after the war before moving to Virginia in 1785. He was minister of what is now Grace Lutheran Church in Winchester, but served congregations in Woodstock and Strasburg as well. He died in 1812 and is buried In Mount Hebron Cemetery in Winchester. His house is still standing. |

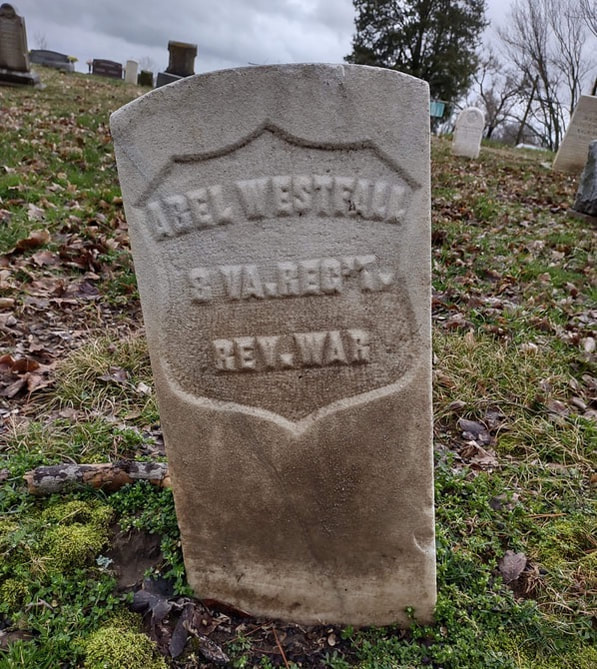

| Capt. Abel Westfall commanded the 8th Virginia’s Hampshire County company. He came from a Dutch family. According to one genealogy, his great-great grandfather arrived in New York in 1642 to manage Gov. Peter Stuyvesant’s farm in New Amsterdam. He raised his company early in 1776 and resigned late in 1777. After the Revolution, he founded the town of Westfall, Ohio. The town no longer exists, but the Westfall School District still carries his name. He moved to Indiana and died there in 1814. He is buried in Bloomfield, Indiana next to his brother. (Sam Zuckschwerdt) |

| Lieutenant Cornelius Westfall began as a sergeant in his brother's company early in 1776. he was commissioned an ensign and promoted to 2nd lieutenant in 1777. He resigned on April 21, 1778. He and his brother moved to Ohio and then to Indiana. Cornelius married a widow, Elizabeth Springstone (nee Lambert) in 1787. He died in 1829. He is buried in Bloomfield, Indiana. (Sam Zuckschwerdt) |

| Henry Wysor enlisted in Capt. Thomas Berry's company in February of 1776 and was chosen to join the Provisional Rifle Corps under Daniel Morgan in 1777. He participated in the victory at Saratoga and witnessed the surrender of General Burgoyne. He went home after his two-year enlistment ended in 1778, but was drafted into the militia in 1781 when General Cornwallis entered Virginia in 1781. Wysor was at Yorktown for the British surrender in October. He died in 1844 and is buried with several members of his family at Wysor cemetery in Pulaski County, Virginia. His artfully-created headstone appears to be one of very few original ones remaining. (Wilderness Road Regional Museum) |

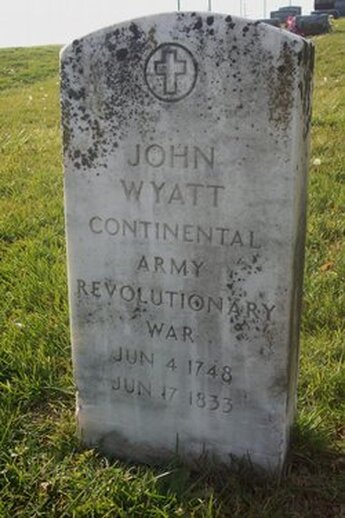

| John Wyatt was born in London and drafted into the 8th Virginia from Botetourt County in February of 1778. He joined the army at Valley Forge and engaged in his first battle at Monmouth at the end of June as part of the merged "4th 8th 12th Virginia Regiment." He reenlisted and was taken prisoner with most of the Virginia line at Charleston in 1780. He was exchanged early enough to be present for the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown. He moved to Kentucky after the war, got married, had one daughter, and is buried in Milroy Cemetery in Rush County, Indiana. |

| Christopher Young enlisted in Jonathan Clark's company on January 28, 1776 and was promoted to corporal on August 1 of the same year. He fought at Brandywine but was assigned to guard the baggage during the Battle of Germantown. After completing his two-year enlistment, he was discharged at Valley forge. He moved to Ohio after the war and lived to be nearly 90 years old. He is buried only a few feet from Lt. Thomas Miller in the "Patriot Square" section at Grandview Cemetery in Chillicothe. |

Memorials and Other Markers

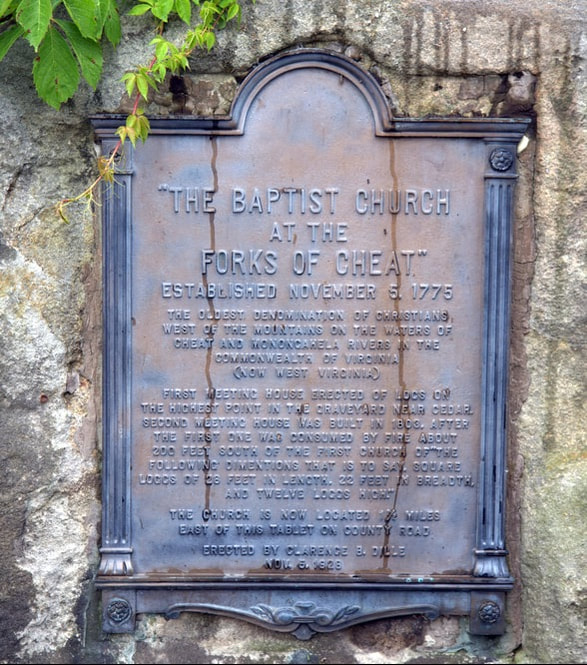

| Richard Cain enlisted in Capt. Abel Westfall's company in February, 1776. He was wounded at Brandywine or Germantown and served the rest of his enlistment in the hospital. He was discharged early in 1778. He married Jean, whose maiden name is not known. He was one of the founders of Forks of Cheat Baptist Church in Monongalia County, West Virginia. The original log church is long gone and there is no surviving marker for Cain, though a plaque marks the site of the original church. |

| A memorial to Sgt. William Combs (also Coombs and Coomes) and other family members in St. Lawrence Catholic in Davis County, Kentucky. Combs enlisted in Capt. Richard Campbell's company in February 1776 and was discharged at Valley Forge two years later. He married Nell Cloud, possibly a relative of Daniel Cloud. He lived in Lincoln County, Kentucky in 1795 and then Bath County in 1818. He was a school teacher. He died in 1840. It is not clear from the marker that he is buried on-site. Moreover, Bath and Davis counties are two hundred miles apart and there appears to be another "Coombs" family in Kentucky at the period that originated from Maryland. Separate genealogies can be seen here and here. |

| Capt.-Lieut. Leonard Cooper was from Shenandoah County and began the war as an ensign in Capt. Richard Campbell's Company. He rose to lieutenant and then "captain-lieutenant" (lieutenant in command of the colonel's company) in 1779. He had a leg amputated after a duel with Maj. Abraham Kirkpatrick and served out the war in the Invalid Corps. He married Christina Throenberger in 1796 and drowned in the Shenandoah River in 1821 after falling from his horse. The grave of another Leonard Cooper, one of the first settlers of Point Pleasant, West Virginia, is mismarked with a stone honoring Capt.-Lieut. Cooper's service. |

| Maj. Peter Helphenstine was born in Germany and emigrated to Winchester in the 1750s with his wife and first son. He died in 1778 or 1779 of complications of malaria contracted during the regiment's tough summer in the Carolinas in 1776. He resigned that summer and returned home, never to recover. He is buried in Mount Hebron Cemetery in Winchester in an unmarked grave. Though a man of stature, he family was left destitute after his death. It is likely that his family could not afford a stone memorial for him when he died and made do with one made of wood. A nearby plaque lists all of the Revolutionary War veterans buried in the historic cemetery. |

| Cpl. Drury Jackson of Capt. George Slaughter's company is buried in Virginia. Though he was in Georgia as a soldier, he never lived there. In the 1930s, the DAR ordered a veteran's headstone for another man with the same name buried in Baldwin County, Georgia. The "real" Drury Jackson enlisted with his brother Utey in 1776. Utey died of malaria in Charleston, but Drury survived the war and lived nearly his whole life in what is now Madison County, Virginia. It appears he moved to nearby Shenandoah County shortly before he died, and he is certainly buried there or (possibly) in Madison. His actual marker is long gone and this memorial to his military service still stills atop another man's grave. |

| This memorial to Enoch Job (also "Jobe") was dedicated by the Rock Island Chapter, DAR in 2018. Job was a former Quaker who enlisted in Captain Clark's company in 1776 but missed the rendezvous and was assigned to Captain Croghan's company for the first year. He was discharged in 1778. He lived in Tennessee and Kentucky before settling in Cole County, Missouri in 1819. He died in 1843. His grave site is not known, but this memorial is at Old Salem Church in Moniteau County. |

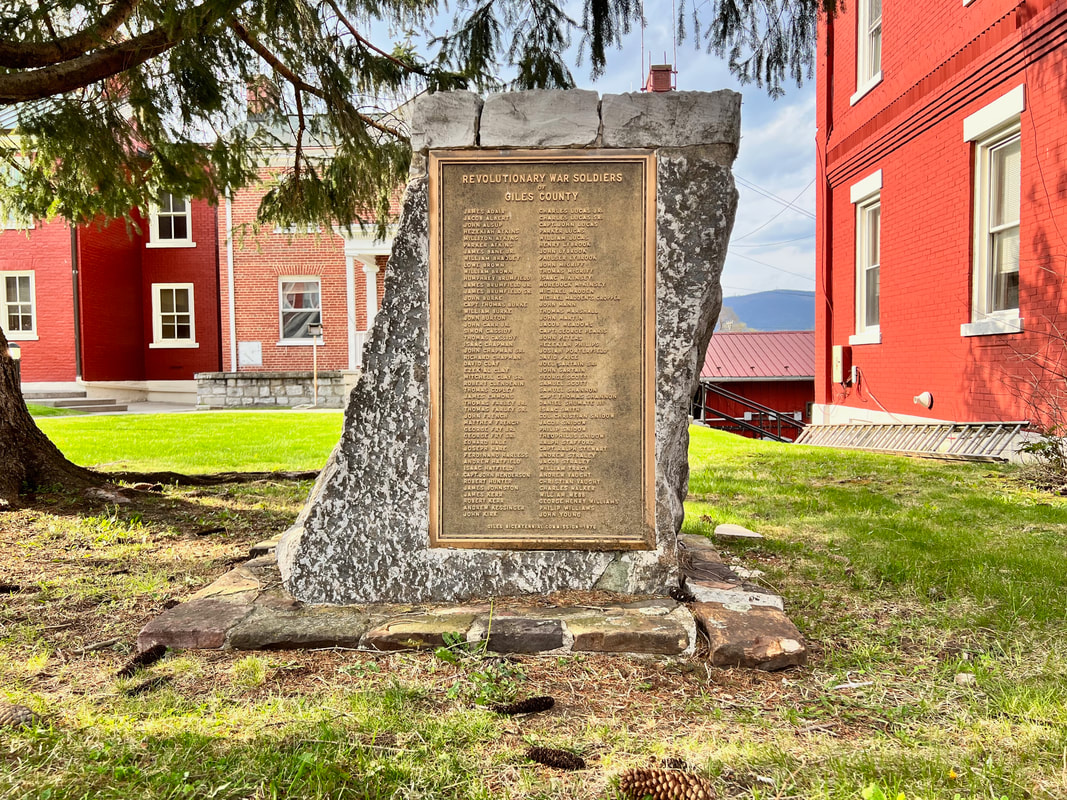

| A Giles County, Virginia memorial honors James Johnston and several other Revolutionary War veterans. Johnston served in Capt. George Slaughter's company from Culpeper and then relocated to what became Giles County. His pension application includes a uniquely complete and coherent summary of the regiment's service. The site of his grave is not known. |

| Sgt. Jacob Kneisley (Nicely) of Capt. Jonathan Clark's company is believed to be buried here in Old Dutch Cemetery in Highland County, Ohio. Kneisley was the son of Swiss immigrants and remembered as a wagon driver before he enlisted early in 1776. He was reported as having deserted on July 2, 1777 but claimed with support from Lt. Jacob Parrott (who was cashiered after Germantown) to have served to the end of the war. He died in 1830. (Findagrave) |

| The possible but unconfirmed grave of John Sloan, a private in Capt. George Slaughter's Culpeper County company. Sloan enlisted for an unusual one-year term in January of 1777, suggesting he may have been a substitute serving out another man's two-year enlistment. Bryant Sloan, likely an older brother, enlisted for two years in the same company early in 1776. Bryant moved to Kentucky and died there. John also appears to have been in Kentucky, participating in the reprisal against New Chillicothe after the Battle of Blue Licks. This grave is in Trinity United Methodist Church's cemetery in Alexandria, Va. It is original, decorated with an SAR medallion, and has dates correct for a man with Sloan's service history. It was rare, however, for veterans to move farther east after the war, particularly after service and known family in Kentucky. |

| Adjutant Francis Swaine was buried in 1820 in the cemetery of Trinity Lutheran Church in Reading, Pennsylvania. He was Colonel Muhlenberg's brother-in-law. In 1779 he became clothier for the Pennsylvania state line and was a general in the state militia in the early 1800s. He was buried "near the walls" of the church. In 1895 it was reported that a "large marble slab (now broken in two) marks his grave, and bears the inscription: 'Gen. Francis Swaine/Born January 2nd, 1754/Died June 17th, 1820.' Several graves that were covered by a church expansion are now listed on two marble slabs. |

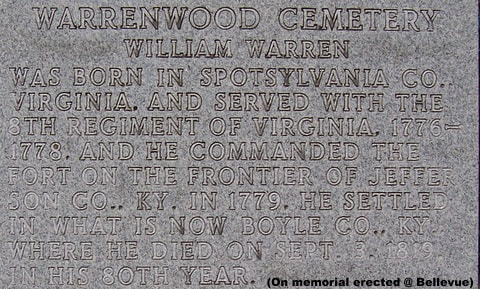

| The family cemetery at Warrenwood, the home of Capt. William Warren, was removed to accommodate road expansion in 1990. Warren enlisted as a private in Capt. Richard Campbell's company in 1776 and served for two years. He was later a captain in the Shenandoah County militia, before moving to Kentucky. His remains are now in a mass grave in Bellevue Cemetery in Danville, Kentucky. |

Gabriel Neville

is researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh.

Categories

All

Artifacts & Memorials

Book Reviews

Brandywine & Germantown

Charleston & Sunbury

Disease

Frontier

Generals

Organization

Other Revolutionary War

Race

Religion

Trenton & Princeton

Valley Forge & Monmouth

Veterans

Archives

March 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

October 2023

July 2023

April 2023

February 2023

January 2023

November 2022

August 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

October 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

April 2019

February 2019

January 2019

November 2018

September 2018

August 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

December 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

April 2017

March 2017

January 2017

November 2016

July 2016

June 2016

January 2016

December 2015

November 2015

October 2015

September 2015

August 2015

February 2015

January 2015

RSS Feed

RSS Feed