- Published on

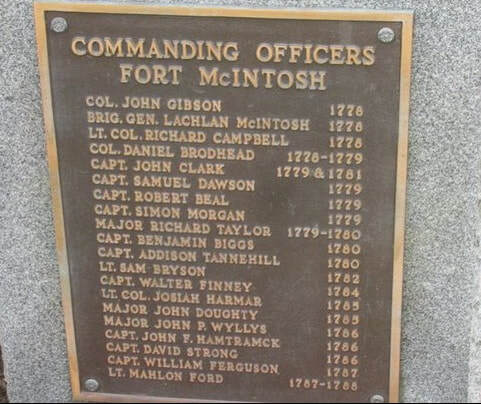

Biggs and Brady at Fort McIntosh

Four of Fort McIntosh's early commanders were veterans of the 8th Virginia: Lt. Col. Richard Campbell, Capt. Robert Beall, Capt. Simon Morgan, and Capt. Benjamin Biggs.

The Knife and Tomahawk

An Unpublished Incident in the Life of Capt. Samuel Brady

by a Western Man

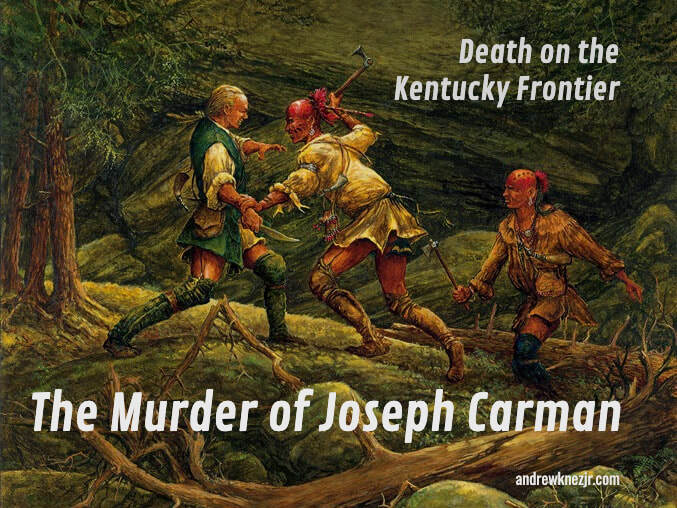

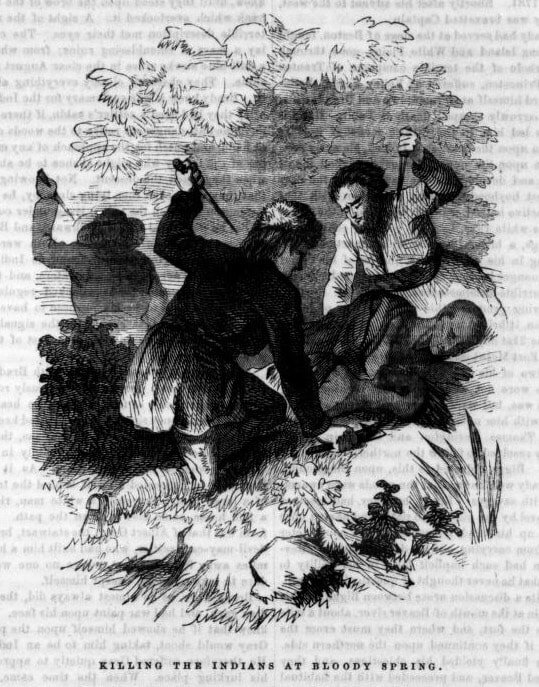

The illustration that accompanied the story in Graham's Illustrated Magazine, with the caption "Killing the Indians at Bloody Spring."

Brady had emigrated westward, or rather had marched thither in 1778, as a lieutenant in the distinguished Eighth Pennsylvania Regiment, under the command of General Richard Broadhead, of Easton. When, in the spring of 1779, McIntosh retired from command in the West, Broadhead succeeded him, and remained at Pittsburg until 1781. Shortly after his advent to the west, Brady was brevetted Captain.

Samuel Brady (Wikipedia).

But, as they approached the edge of the clearing, just outside of the fence, Brady discovered “Indian signs,” as he called them. His companions discovered them almost as quick as he, and at once, in low tones, communicated to each other the necessity for a keen watch. They slowly trailed them along the side of the fence toward the house, whose situation they well knew, until they stood upon the brow of the bluff bank which overlooked it. A sight of the most terrible description met their eyes. The cabin lay a mass of smouldering ruins; from whence a dull blue smoke arose in the clear August sunshine. They observed closely everything about it. Brady knew it was customary for the Indians after they had fired a settler’s cabin, if there was no immediate danger, to retire to the woods close at hand, and watch for the approach of any member of the family who might chance to be absent when they made the descent. Not knowing but that they were even then lying close by, he left Bevington to watch the ruins, lying under cover, whilst he proceeded to the northward, and Biggs southward, to make discoveries. Both were to return to Bevington, if they found no Indians. If they came across the perpetrators, and they were too numerous to be attacked regularly, Brady declared it to be his purpose to have one fire at them, and that it should be a signal for both of his followers to make the best of their way to the fort.

Benjamin Biggs' house north of Wheeling, W.V. shortly before it was taken down about 1960. (West Liberty Historical Society)

Gray, with the instinctive feeling of one who knew there was danger, and with that vivid presence of mind which characterizes those acquainted with frontier life, ceased at once to struggle. The horse had been started by the sudden onslaught, and sprung to one side. Ere he had time to leap forward, Brady had caught him by the bridle. His loud snorting threatened to arouse any one who was near. The Captain soon soothed the frightened animal into quiet.

Gray now hurriedly asked Brady what the danger was. The strong, vigorous spy, turned away his face unable to answer him. The settler’s already excited fears were thus turned into realities. “The manly form shook like an aspen leaf, with emotion—tears fell as large drops of water over his bronzed face. Brady permitted the indulgence for a moment, whilst he led the horse into a thicket close at hand and tied him. When he returned Gray had sunk to the earth and great tremulous convulsions writhed over him. Brady quietly touched him upon the shoulder and said, “Come.” He at once arose, and had gone but a few yards until every trace of emotion had apparently vanished. He was no longer the bereaved husband and father—he was the sturdy, well-trained hunter, whose ear and eye were acutely alive to every sight or sound, the waving of a leaf or the crackling of the smallest twig.

He desired to proceed directly toward the house, but Brady objected to this, and they passed down toward the river bank. As they proceeded, they saw from the tracks of horses and moccasin prints upon the places where the earth was moist, that the party was quite a numerous one. After thoroughly examining every cover and possible place of concealment, they passed on to the southward and came back in that direction to the spot where Bevington stood sentry. When they reached him they found that Biggs had not returned. In a few minutes he came. He reported that the trail was large and broad; the Indians had taken no pains to conceal their tracks—they simply had struck back into the country, so as to avoid coming in contact with the spies whom they supposed to be lingering along the river.

Gray and Bevington obeyed at once, nor did Biggs object. Brady struck the trail and began pursuit in that tremendous rapid manner for which he was so famous. It was evident that if the savages were overtaken, it could only be done by the utmost exertion. They were some hours ahead, and from the number of their horses must be nearly all mounted. Brady felt that if they were not overtaken that night, pursuit would be utterly futile. It was evident that this band had been south of the Ohio and plundered the homes of other settlers. They had pounced upon the family of Gray upon their return.

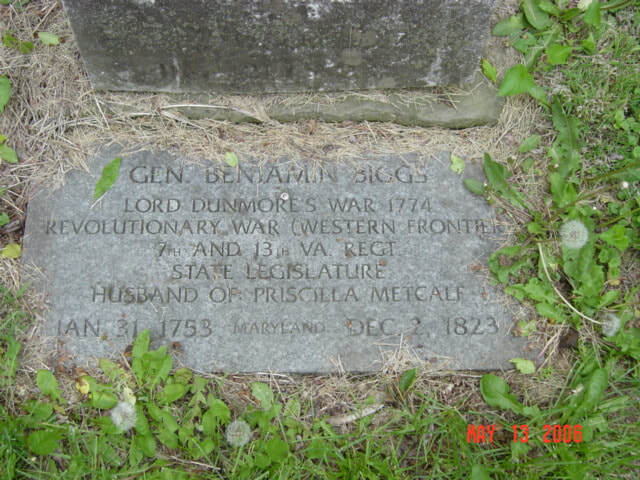

The grave of Gen. Benjamin Biggs in West Liberty, W.V. The stone is broken, with the top half leaning against the base from behind. (Findagrave)

At last, convinced from the general direction in which the trail led, that he could divine with absolute certainty the spot where they would ford that stream, he abandoned it and struck boldly across the country. The accuracy of his judgment was vindicated by the fact, that from an elevated crest of a long line of hills, he saw the Indians with their victims just disappearing up a ravine on the opposite side of the Beaver. He counted them as they slowly filed away under the rays of the declining sun. There were thirteen warriors, eight of whom were mounted—another woman, besides Gray’s wife, was in the cavalcade, and two children besides his—in all, five children.

The odds seemed fearful to Biggs and Bevington; although Brady made no comments. The moment they had passed out of sight, Brady again pushed forward with unflagging energy, nor did his followers hesitate. There was not a man among them whose muscles were not tenseand rigid as whip-cord, from exercise and training, from hardship and exposure. Gray’s whole form seemed to dilate into twice its natural size at the sight of his wife and children. Terrible was the vengeance he swore.

Just as the sun set, the spies forded the stream and began to ascend the ravine. It was evident that the Indians intended to camp for the night some distance up a small creek or run, which debouches into Beaver River, about three miles from the location of Fort McIntosh, and two below the ravine. The spot, owing to the peninsular form of the tongue of the land lying west of the Beaver, at which they expected to encamp, was full ten miles from that fort. Here there was a famous spring, so deftly and cunningly situated in a deep dell, and so densely inclosed with thick mountain pines, that there was little danger of discovery! Even they might light a fire and it could not be seen one hundred yards.

The proceedings of their leader, which would have been totally inexplicable to all others, were partially, if not fully, understood by his followers. At least, they did not hesitate or question him. When dark came, Brady pushed forward with as much apparent certainty as he had done during the day. So rapid was his progress, that the Indians had but just kindled their fire and cooked their meal, when their mortal foe, whose presence they dreaded as much as that of the small-pox, stood upon a huge rock looking down upon them.

His party had been left a short distance in the rear, at a convenient spot, whilst he went forward to reconnoitre. There they remained impatiently for three mortal hours. They discussed in low tones the extreme disparity of the force—the propriety of going to McIntosh to get assistance. But all agreed that if Brady ordered them to attack, success was certain. However impatient they were, he returned at last.

A flat modern marker at the base of Biggs' grave outlines his military and political service. (Findagrave)

After each fairly understood the duty assigned him, the slow, difficult, hazardous approach began. They continued upon their feet until they had gotten within one hundred yards of the foe, and then lay down upon their bellies and began the work of writhing themselves forward like a serpent approaching a victim. They at last reached the very verge of the line, each man was at his post, save Biggs, who had the farthest to go. Just as he passed Brady’s position, a twig cracked roughly under the weight of his body, and a huge savage, who lay within the reach of Gray’s tomahawk, slowly sat up as if startled into this posture by the sound. After rolling his eyes, he again lay down and all was still.

Full fifteen minutes passed ere Biggs moved; then he slowly went on. When he reached his place, a very low hissing sound indicated that he was ready, Brady in turn reiterated the sound as a signal to Gray and Bevington to begin. This they did in the most deliberate manner. No nervousness was permissible then. They slowly felt for the heart of each savage they were to stab, and then plunged the knife. The tomahawk was not to be used unless the knife proved inefficient. Not a sound broke the stillness of the night as they cautiously felt and stabbed, unless it might be that one who was feeling would hear the stroke of the other’s knife and the groan of the victim whom the other had slain. Thus the work proceeded. Six of the savages were slain. One of them had not been killed outright by the stab of Gray. He sprang to his feet, but as he arose to shout his war cry, the tomahawk finished what the knife had begun. He staggered and fell heavily forward, over one who had not yet been reached. He in turn started up, but Brady was too quick, his knife reached his heart and the tomahawk his brain almost at the same instant.

All were slain by the three spies, except one. He started to flee, but a rifle shot by Biggs rang merrily out upon the night air and closed his career. The women and children, alarmed by the contest, fled wildly to the woods; but when all had grown still and they were called, they returned, recognizing amid their fright the tones of their own people. The whole party took up their march for McIntosh at once. About sunrise next morning the sentries of the fort were surprised to see the cavalcade of horses, men, women and children, approaching the fort. When they recognized Brady, they at once admitted him and the whole party,

From that hour to this, the spring is called the “Bloody Spring!” and the small run is called, ‘‘Brady’s Run.” Few, even of the most curious of the people living in the neighborhood, know aught of the circumstances which conferred these names; names which will be preserved by tradition forever. Thus ended one of the very many hand-to-hand fights which the great spy had with the savages. His history is fuller of daring incident, sanguinary, close, hard contests, perilous explorations and adventurous escapes, than that of either of the Hetzels, of Boone or Kenton. He saw more service than any of them, and his name was known as a bye-word of terror among the Indian tribes, from the Susquehanna to Lake Michigan.

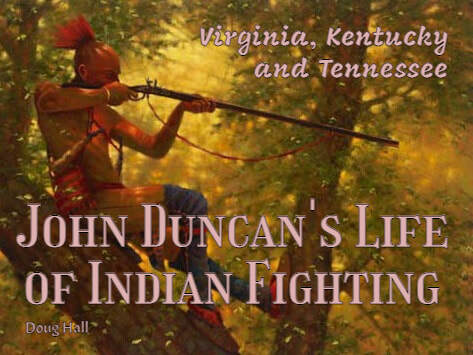

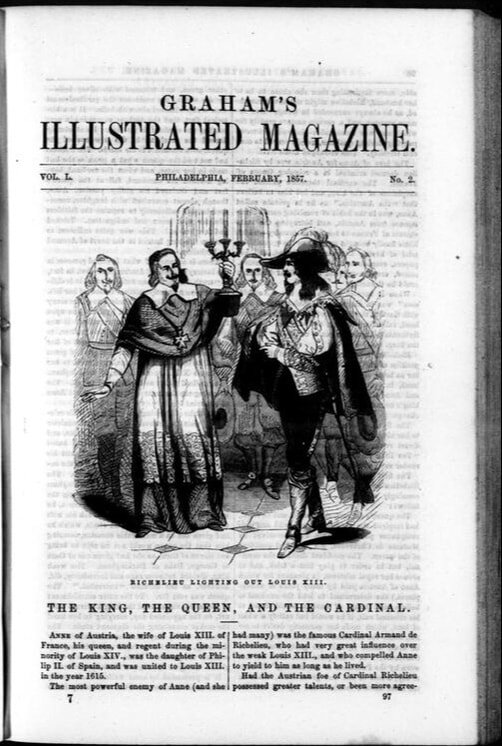

The February, 1857 issue of Graham's Illustrated Magazine.