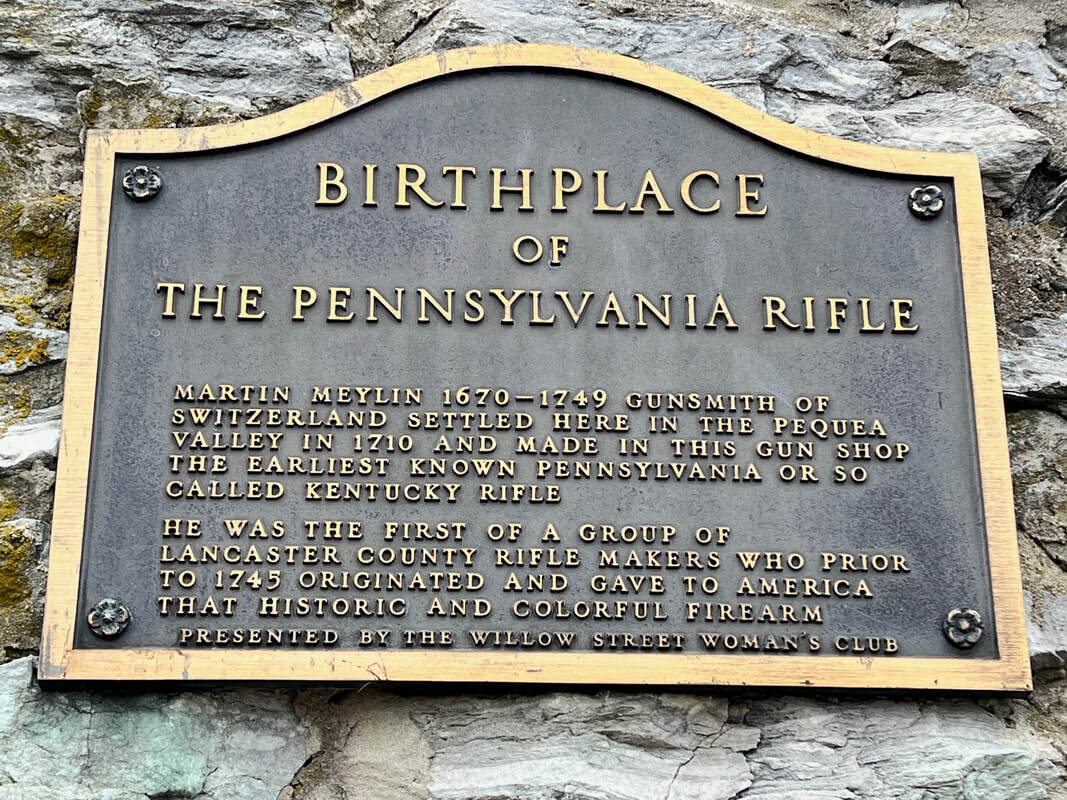

- Published on

"I fought in our Revolutionary War for liberty."

—Sgt. John Vance

"...one of the most perfect battalions of the American Army."

—George Bancroft

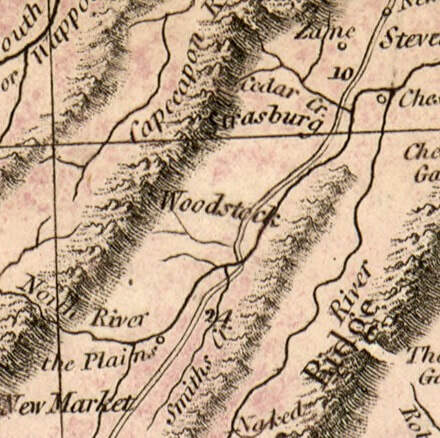

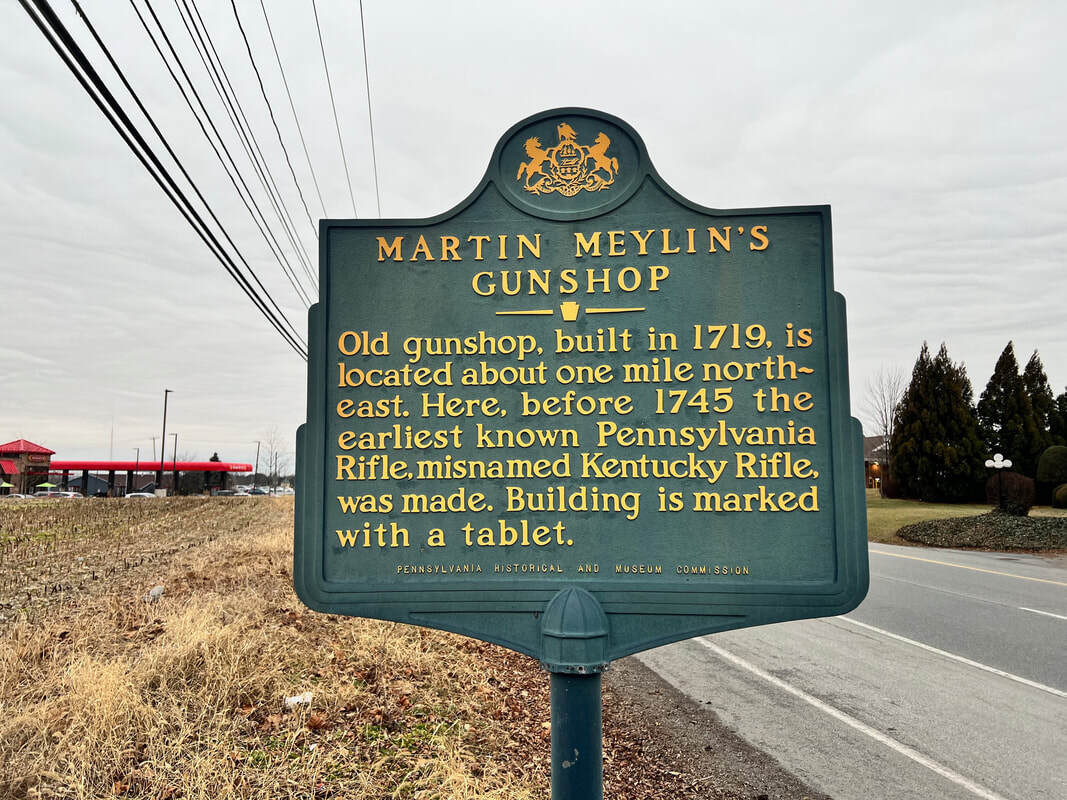

Meylin's gun shop in West Lampeter, Lancaster County, was built about 1718.

An ornate Pennsylvania rifle probably made by George Schreyer Sr. (1739–1819) in York County, Pennsylvania ca. 1770. (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Like the nearby state historical marker, a plaque on the building is prickly about the "so-called Kentucky Rifle." The longrifle was developed in Pennsylvania two or three decades before the earliest white settlement of Kentucky.

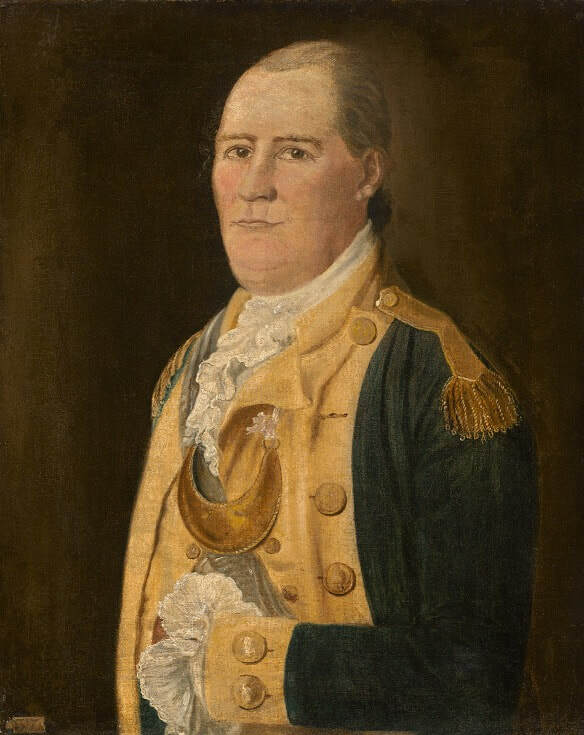

Daniel Morgan commanded men detached from the 8th Virginia during the 1777 Saratoga campaign. He was from Frederick County, which also produced Capt. Thomas Berry's Company. Though in bad physical condition, he came out of retirement to respond to the British invasion of Virginia in 1781.

William Darke was a lot like Morgan in temperament and character. Long before the war, they were both part of a group of young men that engaged in fist fights or wrestling matches at the "Battle Town Tavern," where Berryville is now. Both men rose from rough beginnings to a status they were never fully comfortable with.

Gen. Daniel Morgan’s sword, made about 1776, has Spanish inscriptions that translate to “Draw me not without reason” on one side and “Sheath me not without honor” on the other. (VMHC)

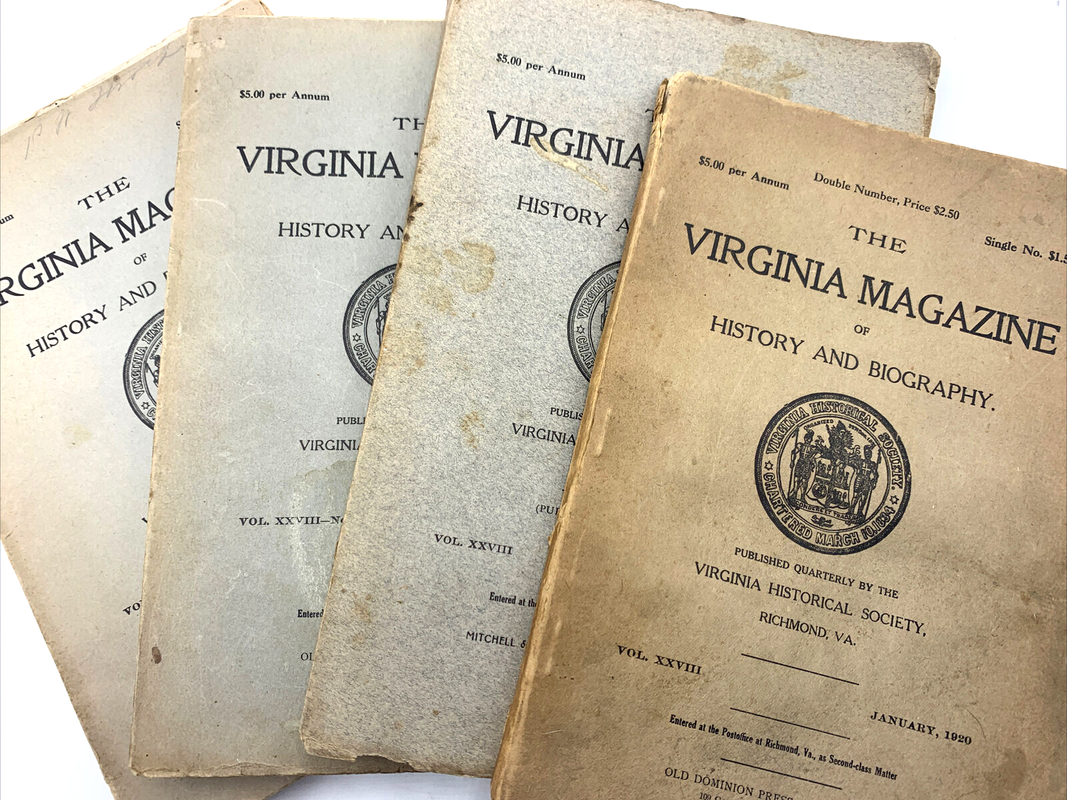

The Continental Dollar

Farley Grubb (University of Chicago, 2023)

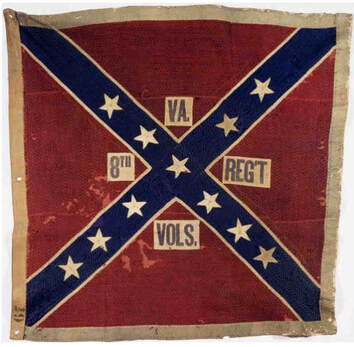

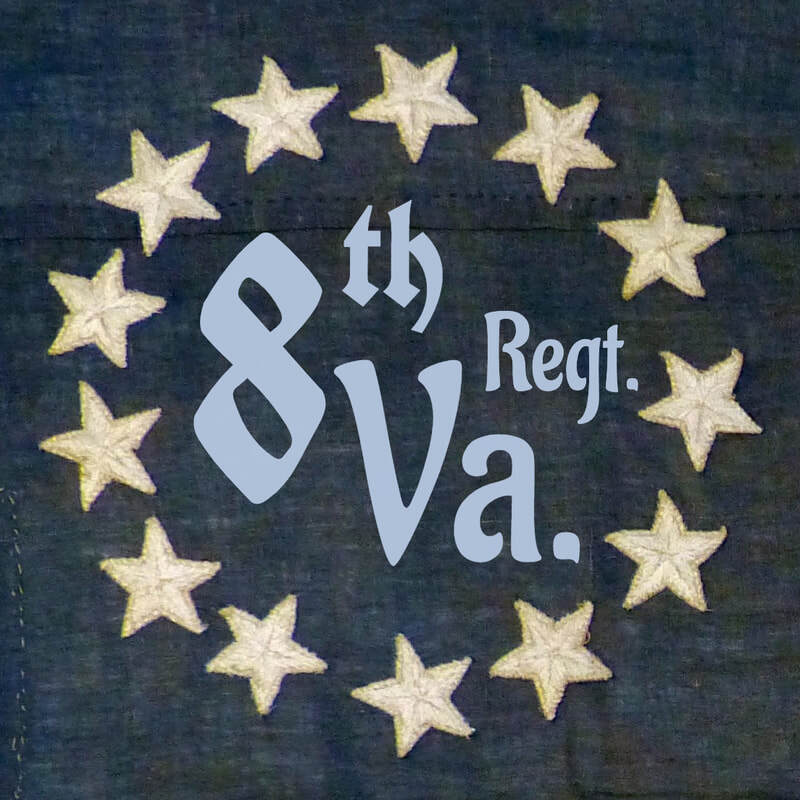

A recreated "grand division banner" of the 8th Virginia. The original survives in a private collection. This was not the regimental banner, but rather one of a pair of flags used for tactical direction.

Members of the James Wood II Chapter, Sons of the American Revolution, hold a modern flag honoring Col. Wood's leadership of the "new" 8th Virginia Regiment, originally the 12th Virginia Regiment. This photo was taken at the grave of Maj. Gen. Adam Stephen, who commanded both regiments in 1777.

The origin of this 8th Virginia flag has not be ascertained. It is visibly old, but may be a recreation. It is owned by a collector.

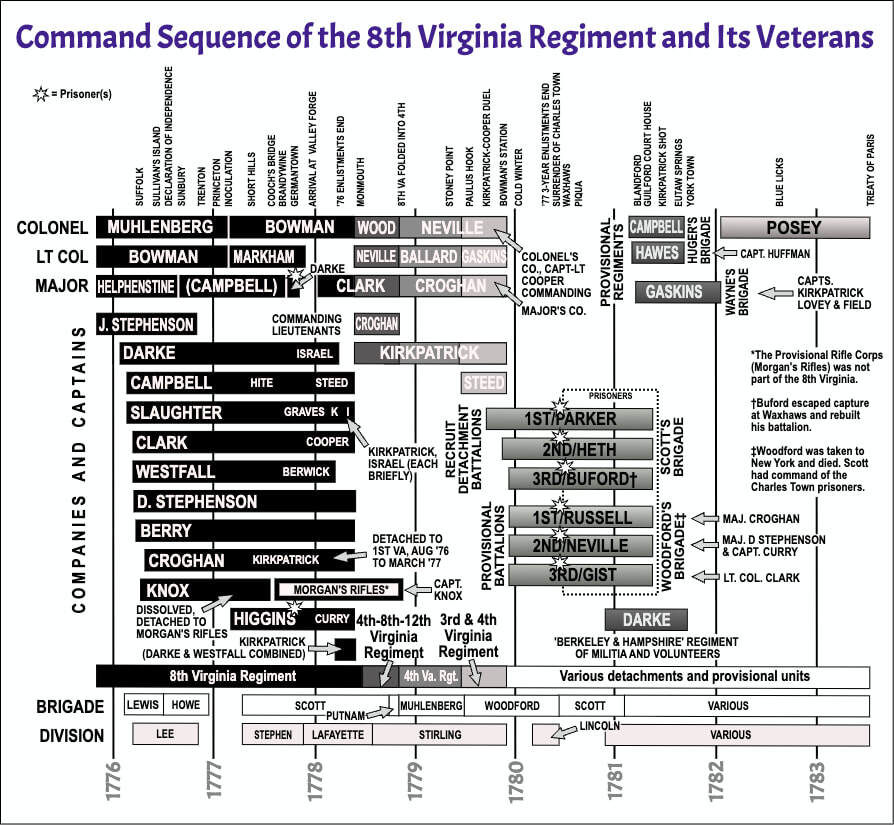

is researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh.