He described the priest’s ornate vestments, the beautiful music, and the bloody crucifix above the altar. “Here is every Thing which can lay hold of the Eye, Ear, and Imagination. Every Thing which can charm and bewitch the simple and ignorant. I wonder how Luther ever broke the spell.” He admitted, though, that the sermon was good. Protestants’ views of Catholics aside, it was the Church itself, and more specifically the Papacy, that presented a problem for the British Empire. The influential political thinker John Locke asserted in his 1689 Letter Concerning Toleration that a “church can have no right to be tolerated by the magistrate, which is constituted upon such a bottom, that all those who enter into it . . . deliver themselves up to the protection and service of another prince.”[3] By tolerating such a church, a ruler would “suffer his own people, to be lifted, as it were, for soldiers against his own government.”[4] The example he used was Islam, but it was Catholicism he was concerned about. Michael Breidenbach is a Cambridge University-educated associate history professor at Ave Maria University, an orthodox Catholic school in Florida. His book Our Dear-Bought Liberty: Catholics and Religious Toleration in Early America illustrates the remarkably rapid transformation of Americans’ treatment of Catholics during the Founding Era. Irish Catholics like Capt. John Barry, Lt. Col. John Fitzgerald, and Col. Stephen Moylan played important roles in the Continental Navy and Army. Maryland’s Charles Carroll signed the Declaration of Independence and held a seat on the Continental Congress’s powerful Board of War. Generals Lafayette and Pulaski were both Catholic, as were the French and Spanish empires that came to America’s aid. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

1 Comment

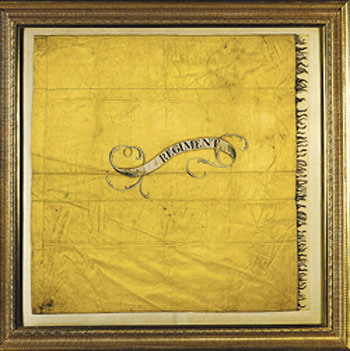

While the Grand Union flag and the Stars and Stripes may have appeared on some battlefields, they were more likely to be seen on forts and ships. Virginia had no state flag until the Civil War. Every regiment, however, had a flag that served important symbolic and battlefield purposes. Regimental flags were unique works of art, often featuring symbols from antiquity or popular culture with mottos in English or Latin. The flags of the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment and Connecticut’s 2nd Continental Light Dragoons are among the very few that survive. There is, however, an 8th Virginia flag that still exists—but it is not the regimental banner. It is a “grand division standard,” one of two that were used to direct halves of the regiment on the battlefield. These were utilitarian devices with little ornamentation. The most important thing about them was their color.

Henry A. Muhlenberg was at that time preparing to publish a biography of his great uncle, the still-useful (but occasionally inaccurate) Life of Major-General Peter Muhlenberg of the Revolutionary Army. The younger Muhlenberg was a member of Congress and quite knowledgeable about his pedigree, but his description of the flag as “the regimental color” was wrong.

"In 2012, the flag was sold at Freeman’s Auction in Philadelphia. Prior to the auction, Freeman’s brought it to Shenandoah County to be displayed. I was lucky that I found out about it just a couple of days prior to the event. I contacted my friend Erik [Dorman] who also was interested in writing about the 8th and we decided to show up in our uniforms. We caused quite a stir when we walked around the corner of the Courthouse into the square. We were immediately enlisted to "guard" the flag and unveil it during the event.”

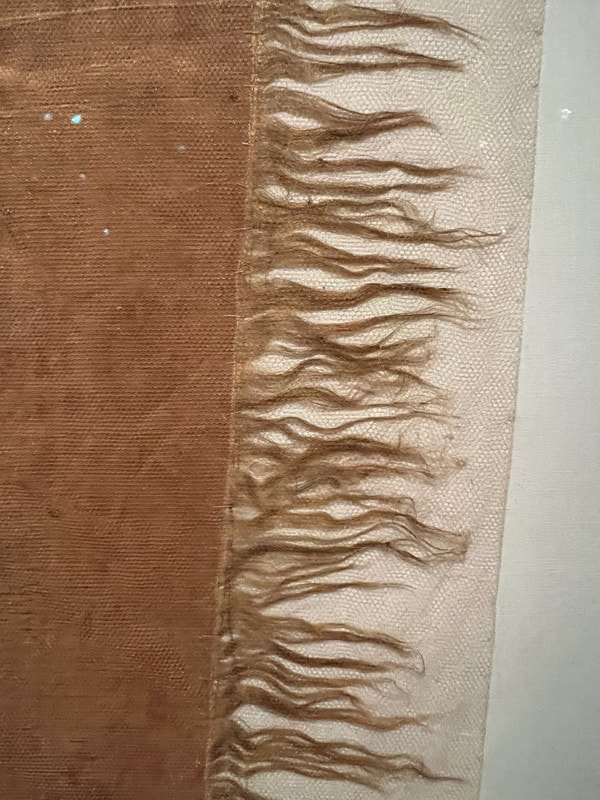

With it were two smaller, plainer flags of identical design but different colors. The 3rd Detachment was an ad hoc unit cobbled together under Col. Abraham Buford in 1780 from new recruits and soldiers who had avoided capture at Charleston earlier that year. The flags were used at the Waxhaws in South Carolina on May 29 when Tarlton defeated Buford there. It is unlikely that the flags were made specifically for the detachment. The regimental flag is described in detail in a 1778 inventory of then-new flags known as the “Gostelowe Return.” The flags were probably, therefore, inherited from a regiment that was folded into Buford’s detachment. Buford had been colonel of the 11th Virginia, and a number of the men in his detachment were reportedly from the 2nd Virginia. The flag could have come from either of those, or from another. The two “grand division” flags from the Buford detachment are almost identical, except for their colors, to the Muhlenberg flag. Buford’s maneuvering flags are blue and yellow. The Muhlenberg flag is a beige color today and was described as a “salmon” color in 1847. A fabric expert advises that the original color was red. The flag has faded considerably just from its time in the frame. It is not hard to imagine it having faded from red to a salmon color over the century or so before it put under glass. The scrolls on the blue and yellow flags contain only the word "regiment." The word is not centered in the scroll, suggesting that a space was retained to the left on both flags to be filled in when they were assigned to a specific regiment. The writing in the 8th Virginia's scroll is illegible now. It was retouched on one side by Mr. Goetz or a previous owner to say "VIII Virg Regt." The 1847 account in the Richmond Whig says the scroll was styled a bit differently as "VIII Virga Regt."

More from The 8th Virginia Regiment |

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed