|

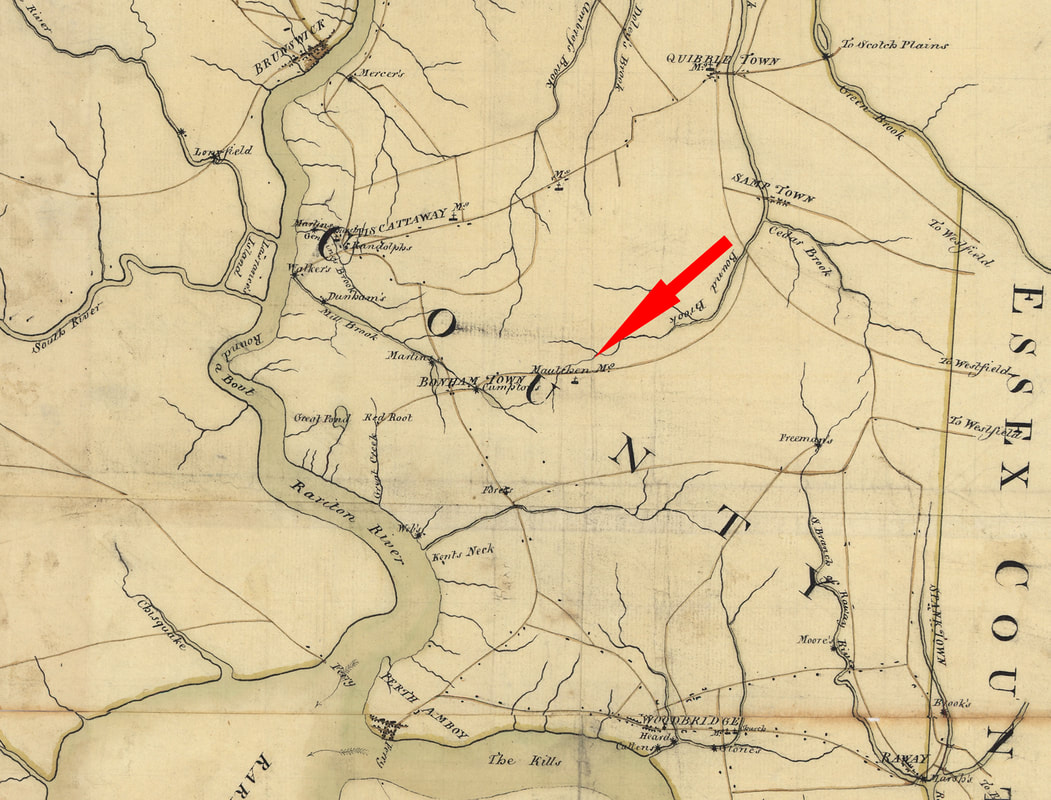

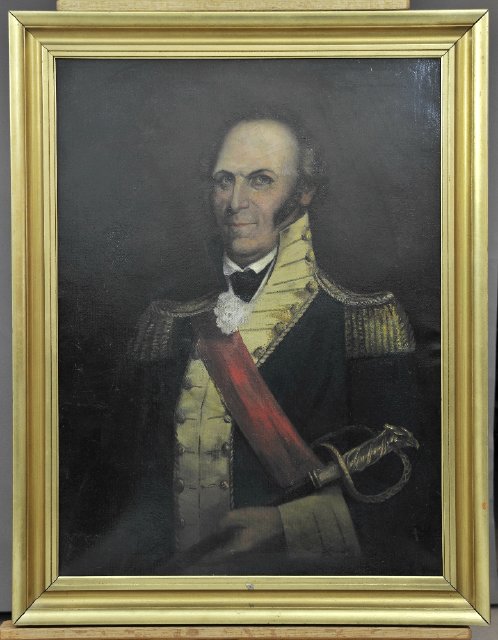

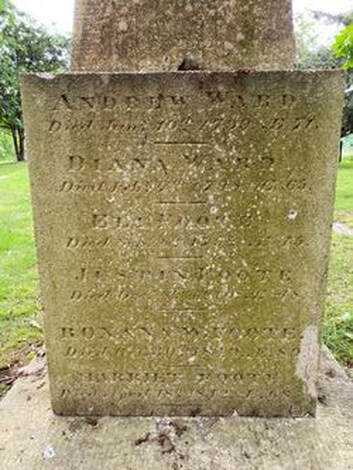

After a couple of quiet days in quarters, McCarty was ordered to have the men ready to march with three days’ provisions. They marched on Thursday, January 23, to Springfield, where McCarty was able to acquire a store of new shoes, stockings, and breeches. The men, some of whom were barefoot, lined up in the snow for the desperately-needed gear. On Saturday evening, his tasks completed, McCarty once again “took a walk to the country, where I got some cyder and a very good supper.” Quartermastering had definite perquisites. Again, on Sunday, he went “into the country,” took some lodgings and “stayed all day.” On Monday, Stephen’s severely understrength brigade headed out to look for the enemy. McCarty followed behind, responsible for the wagons. “Our Virginia troops had marched, and I got orders from General Stephen to follow on, and I marched to Westfield, and then to Scotch Plains, it being in the night and very muddy. I got lodgings at one Mr. Halsey’s.” There was was a regiment of Connecticut men in the field as well, commanded by Col. Andrew Ward. These were one-year men whose enlistments would be up in May. Ward's men had been begging to go home since December, however, and were beginning to desert. McCarty and his wagons caught up with the Virginians, commanded by Col. Charles Scott, and joined them in taking quarters at Quibbletown, a village known today as New Market. McCarty, like the other Virginians, was furious that Ward’s men didn't support them. “There was a body of above 400 men that never came up to our assistance till we retreated. Then they came up, but too late, and only some.” Their anger was soon directed back at the enemy when it was discovered that some wounded Americans had been murdered on the field. Several enemy soldiers (officers, according to McCarty), “went to the field where we retreated from, and the men that was wounded in the thigh or leg, they dash out their brains with their muskets and run them through with their bayonets, made them like sieves. This was barbarity to the utmost.” The murder of the wounded Virginians is confirmed by several sources. General Stephen wrote directly to British general Sir William Erskine to complain that six Virginians “slightly wounded in the muscular parts, were murdered, and their bodies mangled, and their brains beat out, by the troops of his Britannic Majesty.” He warned that such conduct would “inspire the Americans with a hatred to Britons so inveterate and insurmountable, that they never will form an alliance, or the least connection with them.” Stephen could think of no better threat than a reprise of Gen. Edward Braddock’s defeat in the French and Indian War. Stephen used his credentials as a survivor of that battle to insult and to intimidate the British general with over-the-top threats of Indian cannibalism. I can assure you, Sir, that the savages after General Braddock’s defeat, notwithstanding the great influence of the French over them, could not be prevailed on to butcher the wounded in the manner your troops have done, until they were first made drunk. I do not know, Sir William, that your troops gave you that trouble. So far does British cruelty, now a days, surpass that of the savages. In spite of all the British agents sent amongst the different nations, we have beat the Indians into good humour, and they offer their service. It is their custom, in war, to scalp, take out the hearts, and mangle the bodies of their enemies. This is shocking to the humanity natural to the white inhabitants of America. However, if the British officers do not refrain their soldiers from glutting their cruelties with the wanton destruction of the wounded, the United States, contrary to their natural disposition, will be compelled to employ a body of ferocious savages, who can, with an unrelenting heart, eat the flesh, and drink the blood of their enemies. I well remember, that in the year 1763, Lieutenant Gordon, of the Royal Americans, and eight more of the British soldiers, were roasted alive, and eaten up by the fierce savages that now offer their services. The fundamental British strategy in the Revolution was to empower Loyalists and to pacify rebels and persuade them to accept offers of amnesty. The plan clearly wasn’t working. Shortly after the Battle of Drake’s Farm, a loyalist wrote home: “For these two month[s], or nearly, we have been boxed about in Jersey, as if we had no feelings. Our cantonments have been beaten up; our foraging parties attacked, sometimes defeated, and the forage carried off from us; all travelling between the posts hazardous; and, in short, the troops harassed beyond measure by continual duty.” The Forage War was a brilliant (and still-unheralded) success for the Americans. Denying the enemy forage and forcing them to live in close quarters for several months had a cumulatively severe impact on them. Howe had more than 31,000 troops at New York on August 27, 1776. When spring came, he had lost between forty and fifty percent of those men to death, desertion, capture, or disease. That was not sustainable.  The Battle of Drake's Farm occurred at nor near Metuchen, N.J., half-way between major British outposts at New Brunswick and Perth Amboy. This 1781 map was drawn four years after the engagement. This map is oriented ninety degrees to the right of standard orientation, with the right facing to the north. (Library of Congress) More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

7 Comments

Monument Park in the town of Fort Lee, New Jersey, marks the spot of the historic fort. (Author) Monument Park in the town of Fort Lee, New Jersey, marks the spot of the historic fort. (Author) On September 22, 1776, William Croghan’s detachment of men from the 8th Virginia arrived at Fort Constitution, high on a cliff looking over the Hudson River and the island of Manhattan. Very soon, they would be part of the most famous campaign of the war. Months earlier, when the 8th Virginia first formed, its ten companies were ordered to rendezvous at Suffolk, Virginia—south and across the James River from the provincial capital at Williamsburg. Those from the far frontier were the last to arrive. Captain James Knox’s company from Fincastle County (now the state of Kentucky and parts of far southwest Virginia) arrived just in time to join the Regiment as it headed south to with General Charles Lee to defend Charleston. Captain William Croghan’s company from Pittsburgh came too late. His company and several dozen stragglers from other companies were attached for the season to the 1st Virginia and sent north to reinforce Washington at New York. After a march that took more than a month, the 1st Virginia arrived at a fort overlooking the Hudson. It was called Fort Constitution, but was soon renamed Fort Lee after General Charles Lee got (only partially deserved) credit for the glorious June 28 victory at Sullivan's Island in South Carolina. Fort Lee was commanded by Gen. Nathanael Greene and, with Fort Washington across the river, was charged with maintaining patriot control of the strategically critical waterway.  The George Washington Bridge spans the Hudson River between the sites of Fort Lee and Fort Washington. The two forts guarded the strategically important waterway. (Author) The George Washington Bridge spans the Hudson River between the sites of Fort Lee and Fort Washington. The two forts guarded the strategically important waterway. (Author) Sergeant William McCarty recorded their arrival. After ferrying across the Passaic River they “marched to the fort, which we came by several camping places and camps on top of a high hill by the North [Hudson] River.” They “halted in sight of the fort and river till Colonel [James] Read [of the 1st Virginia] went to speak to General Greene.” He “returned shortly” and “ordered us to march back up the hill a piece, where it was late when we pitched camp.” For the next few days, the roughly 140 8th Virginia men under Captain Croghan rested and celebrated after their long march. They were issued flour, beef and rum. They got paid for the first time. On the third day there, McCarty wrote “We lay there and our men drunk very hard as they had plenty of money.”  A reconstructed artillery emplacement overlooks Manhattan from the Palisades. (Author) A reconstructed artillery emplacement overlooks Manhattan from the Palisades. (Author) Things soon turned serious, however. The day after their arrival, soldiers across the river were assembled to witness the execution of a man—bound, blind-folded, and kneeling—for cowardice (Washington gave him a last-minute reprieve). In addition to that news, Croghan’s men also learned that the Hessians and Scottish Highlanders had given no quarter at the Battle of Long Island the month before and had shot as many as seventeen Americans in the head after they had surrendered at Kip’s Bay. If they did not already know it, they now understood that there was no romance in war. Four days after their arrival, still at Fort Lee atop the Jersey Palisades, they watched British maneuvers in the river below. McCarty wrote, “The force heard the cannon fire very brisk from the shipping of the English, and we could see them land. We could easy see their camps and every turn they would make.”  A reconstructed block house with a modern skyscraper looming behind it. (Author) A reconstructed block house with a modern skyscraper looming behind it. (Author) Their stay at the fort was brief. Private Jonathan Grant later attested that they traveled through the Jerseys “to fort Lee on the North River & thence crossed the River to Fort Washington. The enemy at that time was in New York.” Similarly, Private Henry Gaddis recalled that they traveled “to Fort Lee, then we crossed over the North river to Fort Washington.” They joined the 3rd Virginia to form a small, temporary brigade commanded by Col. George Weedon. Now part of the main arm, they were thrust into battle—first at White Plains and later at Trenton. In January, only a handful of them were still well enough to participate in the critical victory at Princeton. The site of Fort Lee and its surrounding camps and artillery emplacements have been partially preserved. Judging purely from McCarty’s account it appears that much of the camping area has been blasted away to make room for the George Washington Bridge. Some of what remains has been preserved as Fort Lee Historic Park. The visitor center and its displays date from the 1976 Bicentennial and, though a bit worn down, still tell the story well. Reconstructed buildings and artillery batteries illustrate the site’s purpose despite the massive bridge and surrounding skyscrapers that make the area look very different from they way it was in the fall of 1776. The position of the actual fort is in the middle of the town of Fort Lee and called Monument Park. An artistic monument records the presence of the fort and the events that occurred there. Fort Lee was abandoned during the retreat through New Jersey, a retreat the fort’s namesake pointedly did nothing to assist with. Lee was in fact captured by the enemy and began to advise them on how to defeat the Continentals—a story told in this earlier post. One has to wonder how many people who live in Fort Lee today have any idea that their town is named for a traitor. Read More: Fort Lee's Despicable Namesake More from The 8th Virginia RegimentAfter the grueling marches to and from Trenton, only a handful of Captain William Croghan’s Pittsburgh men were able to continue on to the Battle of Princeton on January 3, 1777. Princeton was a key American victory. It proved that Trenton wasn’t just a fluke, and it breathed new life into a cause that was just about exhausted. At Williamsburg, the company’s core of about 70 men had been boosted to 140 by the addition of stragglers who had missed the 8th Virginia Regiment’s rendezvous. The company, attached to the 1st Virginia for the year, was at the very center of the action at Trenton, lined up only a few yards from the commander in chief. The marches to and from Trenton were much harder on the men than the battle itself. By the time Washington crossed the Delaware again for another go at the enemy, only a fraction of the men were able to go with him. A mere 20 men from the 1st Virginia were healthy enough to join. Of them, only five can be shown from pension records to have been from Croghan’s detachment from the 8th Virginia —one twenty-third of the original 140. The rest were dead, had deserted, or were sick in camp on the other side of the river. Even Croghan seems to have been absent, leaving Lieutenant Abraham Kirkpatrick in command. Kirkpatrick was a tough, mean, and belligerent man, but also an effective soldier. With him were privates Henry Brock, Harmon Commins, Jonathan Grant, David Williams, and perhaps others who left no record of their presence. All three of the 1st Virginia's field officers were wounded or sick, leaving command to Captain John Fleming. These men, together with the remnants of three other Continental regiments and 200 Pennsylvania state (not Continental) riflemen, were Washington’s advance force, under Brigadier General Hugh Mercer’s command. Fleming’s men went first as they clambering over the icy banks of a ravine and proceeded through an orchard. On the other side of the trees they found fifty dismounted British dragoons lying prone behind a split-rail fence. The dragoons rose and fired a volley. As often happened, this first volley went over their heads—splitting the branches of the fruit trees above them. The dragoons retreated about 40 feet to reload as they were reinforced by a British infantry regiment.

Captain Fleming was killed. His lieutenant, Bartholomew Yeates, was sadistically shot, stabbed, beaten and left to die. Lieutenant Abraham Kirkpatrick was wounded too, but also fortunate enough to be carried off the field by Private Grant. The British captured a cannon, turned it around, and fired it as the Americans ran. Colonel John Haslet of Delaware, attempting to rally the men behind a farm building, was shot through the head and “dropt dead on the spot.” A unit of Philadelphia Associators (militia) arrived to help, but were also quickly forced to retreat. With the Revolution itself hanging in the balance, George Washington brought more reinforcements and daringly risked his own life rallying the troops. “At this moment Washington appeared in front of the American army,” recalled a Pennsylvania state rifleman, “riding toward those of us who were retreating, and exclaimed ‘Parade with us, my brave fellows, there is but a handful of the enemy, and [we] will have them directly.’” The American soldiers were moved, physically and emotionally. “I shall never forget what I felt at Princeton on his account,” wrote one of the Philadelphia Associators, “when I saw him brave all the dangers of the field and his important life hanging as it were by a single hair with a thousand deaths flying around him. Believe me, I thought not of myself.” In the battle that followed, Washington and his men were victorious. After the devastating losses of 1776, Washington had learned to win smaller battles fought on his own terms and to avoid major set-piece battles like those he had lost in New York. Most importantly, his countrymen believed again that they could win. The death of Hugh Mercer, a former commandant of Fort Pitt during the French and Indian War, was widely mourned. Today, eight states have counties named for him and there are countless towns, streets, and schools named in his honor. Unfortunately, the central importance of the battle in which he, Colonel Haslet, Captain Fleming, and Lieutenant Yeates gave their lives is lost on too many people today--including the people who own the ground on which they fought. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

Croghan commanded the remnants of a 140-man detachment that included his own company from Pittsburgh, and another seventy 8th Virginia soldiers who had missed the spring rendezvous at Suffolk, Virginia. For the year, Croghan's men were attached to the 1st Virginia Regiment. That regiment's field officers (colonel, lieutenant colonel, and major) were all sick or wounded, so a man of Croghan's own rank was in command: Capt. John Fleming from Goochland, Virginia. In a week, even Fleming would be dead. There is good reason to think that Croghan was also too sick to command his men and that Lt. Abraham Kirkpatrick (also from Pittsburgh) stepped up to lead. The crossing and the all-night march to Trenton were arduous. The bloody footprints in the snow we learned about in school were very real. Men who sat too long on the way to Trenton froze to death. But the suffering resulted in a victory over the Hessians that revived the American cause. “[B]eat the damn Hessians and took 700 and odd prisoners,” wrote Sgt. Thomas McCarty in his diary. The march back was even worse than the approach. A week later, at the battle of Princeton, only a handful of Captain Croghan's men were fit for service. At Trenton, Croghan's men fired on the enemy just yards in front of General Washington and alongside the soldiers of Colonel George Weedon's 3rd Virginia. Their victory, though small in military terms, revived a dying cause. Afterward, the overconfident British became more cautious and Washington found a tactical model for victory against an enemy that was better trained and equipped. Thereafter, Christmas would always carry a special meaning for those who were there. After the war George Weedon wrote a song that was sung each year at a large party he held at his home in Virginia. The song was remembered by the orphaned son of Gen Hugh Mercer, who died at Princeton. The younger Mercer knew Weedon as his “uncle and second father.” He recalled that for “many years after the Revolution my uncle celebrated at ‘The Sentry Box’ (his residence, and now mine) the capture of the Hessians, by a great festival—a jubilee dinner, if I may so express myself—at which the Revolutionary officers then living here and in our vicinity, besides others of our friends, were always present. It was an annual feast, a day or so after Christmas Day, and the same guests always attended. …I was young, and a little fellow, and was always drawn up at the table to sing ‘Christmas Day in ’76'…. It was always a joyous holiday at ‘The Sentry Box.’” Christmas Day in '76 On Christmas Day in seventy-six Our ragged troops, with bayonets fixed, For Trenton marched away. The Delaware ice, the boats below, The light obscured by hail and snow, But no signs of dismay. Our object was the Hessian band That dare invade fair Freedom’s land, At quarter in that place. Great Washington, he led us on, With ensigns streaming with renown, Which ne’er had known disgrace. In silent march we spent the night, Each soldier panting for the fight, Though quite benumbed with frost. Green on the left at six began, The right was with brave Sullivan, Who in battle no time lost. Their pickets stormed; the alarm was spread The rebels, risen from the dead, Were marching into town. Some scampered here, some scampered there, And some for action did prepare; But soon their arms laid down. Twelve hundred servile miscreants, With all their colors, guns, and tents, Were trophies of the day. The frolic o’er, the bright canteen In center, front, and rear, was seen, Driving fatigue away. And, brothers of the cause, let’s sing Our safe deliverance from a king Who strove to extend his sway. And life, you know, is but a span; Let’s touch the tankard while we can, In memory of the day. [Updated 12/25/20] More from The 8th Virginia Regiment On December 14, 1776, the 8th Virginia’s Sergeant Thomas McCarty wrote in his diary, “I lay in camp and the excessive cold weather made me very unwell.” He and the rest of Washington’s army lay shivering on the west bank of the Delaware River, temporarily safe from the enemy who had chased them all the way from New York. This was the Revolution’s darkest time. Washington was losing. Badly. His troops were barefoot and hungry, and most of their enlistments were about to expire. People were giving up. Richard Stockton, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, swore allegiance to the King. Many others believed the cause was lost. For the enlisted men, the immediate problem was the historically cold December weather. McCarty had frostbite. “I had great pain with my finger,” he wrote on December 9, “as the nail came clean off.” For shelter, he made a hut out of tree branches. It burned down on the thirteenth, along with nearly everything he had. McCarty and the other men in Captain William Croghan’s company of Pittsburgh men had had it rough. They were separated from the rest of the regiment by hundreds of miles because they had missed the spring rendezvous at Suffolk, Virginia. Now, freezing in the snow after being hounded across New Jersey by the enemy, things looked very bleak. In two weeks, most of the army would go home—but not Croghan's men. Soldiers from Virginia (including Pittsburgh) were on two year enlistments. On December 14, 1776, it looked like they would remain behind only to see the Revolution’s last gasp. But things were about to look very different.

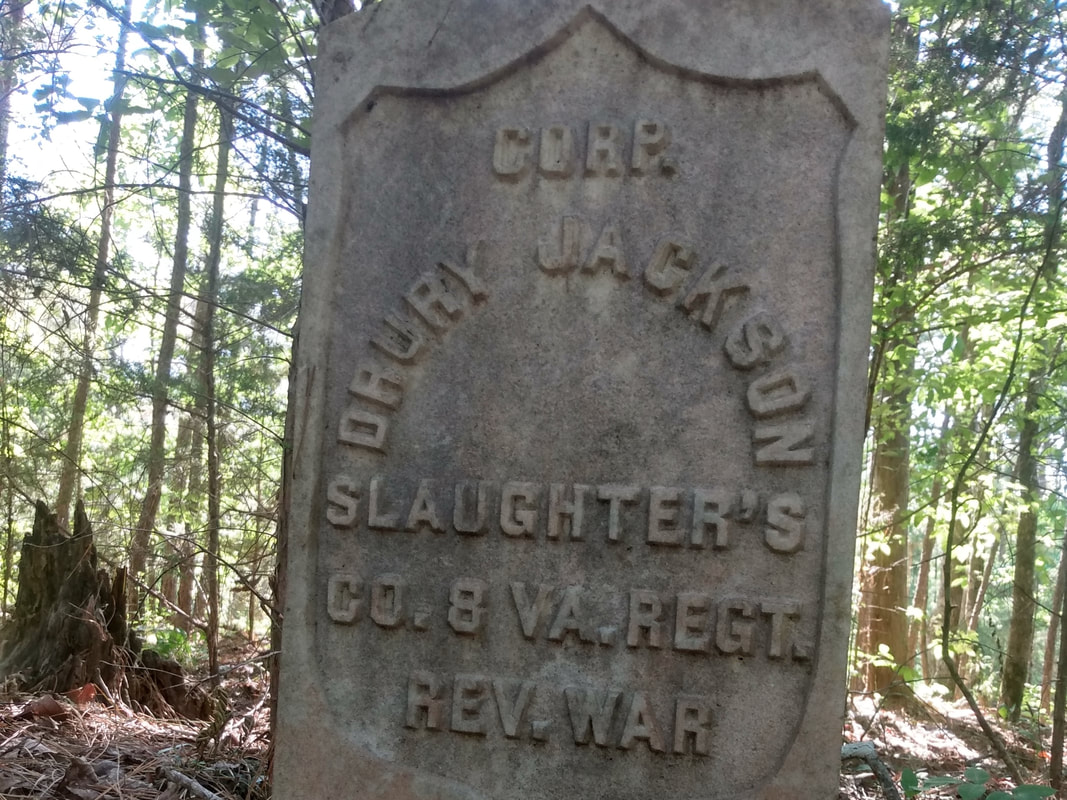

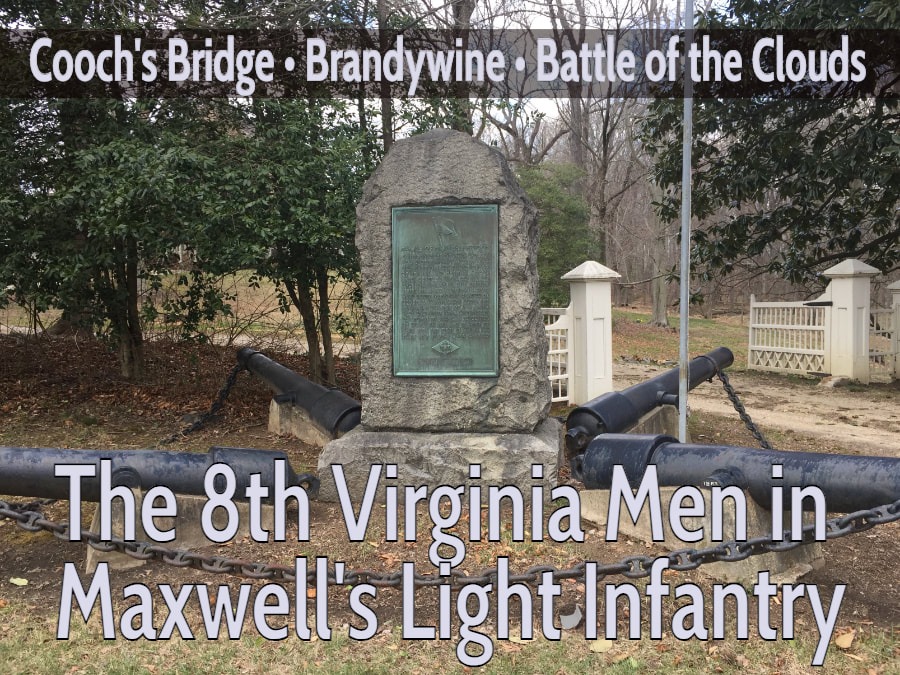

In 1777, the main body of the regiment served in Maj. Gen. Adam Stephen's division at Brandywine and Germantown. A small group of riflemen from the 8th were detached to Daniel Morgan’s Rifle Battalion under the command of Captain James Knox and participated in the Saratoga campaign. A few dozen were detached for a month to William Maxwell's Light Infantry in August and September of 1777 under the command of Captain (later and retroactively Major) William Darke, at Cooch's Bridge and Brandywine. Stephen was replaced by the Marquis de Lafayette late in the year. In 1778, with its ranks severely depleted by disease, casualties, and expired enlistments, the 8th was folded into the 4th Virginia after the Battle of Monmouth. 1776 Southern Campaign (Sullivan’s Island, Savannah, Sunbury): Gen. George Washington, Commander in Chief (not present) Maj. Gen. Charles Lee, Commander of the Southern District Brig. Gen. Andrew Lewis (Tidewater service) Brig. Gen. Robert Howe (Cape Fear, Charleston, Savannah, Sunbury) Captain Croghan Detachment attached to 1st Virginia (White Plains, Trenton, Assunpink Creek, Princeton): Maj. Gen. Joseph Spencer (White Plains) Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene (Trenton and Princeton) Col. George Weedon (temporary brigade at Fort Washington) Brig. Gen. William Alexander, Earl of Stirling (White Plains through Trenton) Brig. Gen. Hugh Mercer (Princeton) 1777 Philadelphia Campaign (Brandywine, Germantown, Valley Forge) Gen. George Washington, Commander in Chief Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln (New Jersey rendezvous) Maj. Gen. Adam Stephen (Brandywine, Germantown) Maj. Gen. Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette (Valley Forge) Brig. Gen. Charles Scott Captain Knox Detachment under Colonel Daniel Morgan (Saratoga) Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln Captain Darke Detachment in Maxwell's Light Infantry (Cooch's Bridge, Brandywine) Brig. Gen. William Maxwell 1778 Campaign (Valley Forge, Monmouth): Gen. George Washington, Commander in Chief Maj. Gen. Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette Maj. Gen. Charles Lee (at Monmouth) Brig. Gen. Charles Scott Col. William Grayson (temporary brigade commander at Monmouth) More from The 8th Virginia Regiment |

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed