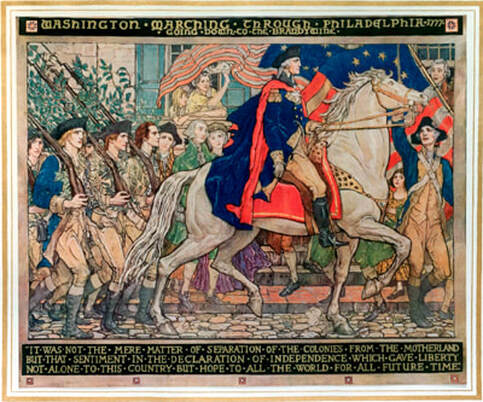

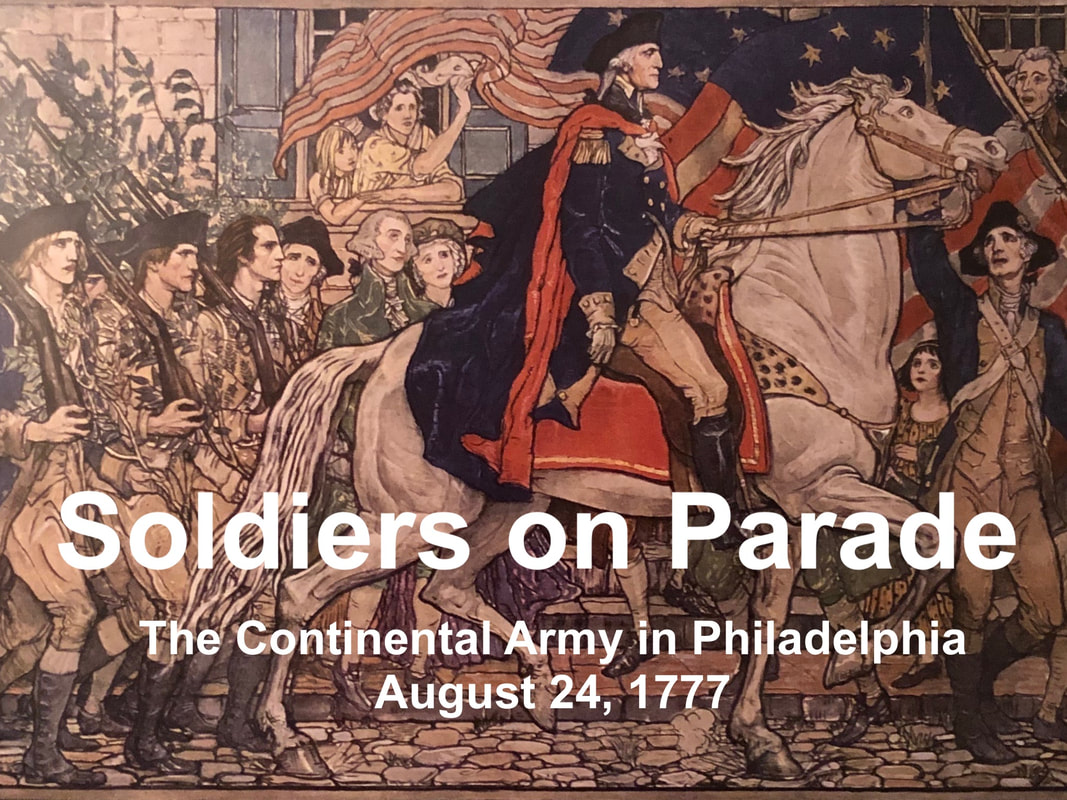

The Continental Army's August 24, 1777 parade through Philadelphia is memorialized in this painting by Violet Oakley in the Pennsylvania state capitol. (Commonwealth of Pennsylvania) The Continental Army's August 24, 1777 parade through Philadelphia is memorialized in this painting by Violet Oakley in the Pennsylvania state capitol. (Commonwealth of Pennsylvania) “The men are to be excused from carrying their Camp Kettles tomorrow,” announced General Washington in his general orders on August 23, 1777. The heavy cast-iron kettles were hated objects that often served only to mock hungry soldiers who had nothing to cook in them. They also did not add to the air of martial precision that Washington wanted his army to convey as it prepared to march through Philadelphia the next day. Congress would be watching, and Washington wanted his army to be impressive. A show of strength was also important for the city’s many loyalist, pacifist, and vacillating eyes. The men were ordered to go to bed early. No passes to leave camp were to be allowed except for urgent business. In the morning, “great attention” was to be paid by officers to ensure “that the men carry their arms well, and are made to appear as decent as circumstances will admit.” The army was ordered to be up and ready to march at four o’clock sharp. The commander in chief played choreographer, specifically arranging the units of his army. He wanted no “strollers,” but rather “strongly and earnestly enjoined” his officers to “make all their men who are able to bear arms…march in the ranks” in order to project the very best order and discipline. “There is to be no greater space between the divisions, brigades and regiments, than is taken up by the Artillery, and is sufficient to distinguish them.” The order of march was precisely arranged. Leading the parade was a subaltern officer with twelve light horsemen, followed two hundred yards behind by a complete troop of cavalry. After another hundred yards came a company of pioneers carrying their axes and shovels in proper order. Four divisions of infantry followed. Leading the way, from Green’s division, was one regiment from General Muhlenberg’s brigade. Then came the rest of Muhlenberg’s brigade followed by General Weedon’s. Adam Stephen’s division followed: Woodford’s brigade first and then Charles Scott’s. Each of these brigades was preceded by its field artillery. Col. Abraham Bowman’s 8th Virginia men, now in their second year of service, were in Scott's brigade. Behind Scott, in the center of the procession, came the artillery park and its artificers. Then Benjamin Lincoln’s division, now commanded by Anthony Wayne, and most of Lord Stirling’s division. These latter brigades were each followed by their field artillery. William Maxwell’s New Jersey brigade, from Stirling’s division, completed the procession of foot soldiers followed by the final two troops of cavalry. As they marched, drums and fifes were arranged in each brigade’s center. Washington ordered “a tune for the quick step played, but with such moderation, that the men may step to it with ease; and without dancing along, or totally disregarding the music, as too often has been the case.” The single-column parade entered the city from the north on Front Street, along the Delaware River, and then turned west on Chestnut Street where it passed the State House (Independence Hall) and the critical gaze of Congress. The soldiers continued on, exited the city, and crossed the Schuylkill River at Middle Ferry where they reunited with the baggage wagons and their cast iron camp kettles. John Adams, after watching the parade, wrote home to Abigail. “The Army, upon an accurate Inspection of it, I find to be extreamly well armed, pretty well cloathed, and tolerably disciplined. … Much remains yet to be done. Our soldiers have not yet, quite the Air of Soldiers. They don’t step exactly in Time. They don’t hold up their Heads, quite erect, nor turn out their Toes, so exactly as they ought. They don’t all of them cock their Hats -- and such as do, don’t all wear them the same Way.” Pondering what he saw, Adams observed, “Discipline in an Army is like the Laws in civil Society. There can be no Liberty, in a Commonwealth, where the Laws are not revered, and most sacredly observed, nor can there be Happiness or Safety in an Army, for a single Hour, where the Discipline is not observed. Obedience is the only Thing wanting now for our Salvation -- Obedience to the Laws, in the States, and Obedience to Officers, in the Army.” The 8th Virginia’s Captain Jonathan Clark made a much more concise record of the day’s activities: “Rain. Marched thro Philadelphia, cross’d Schuylkill and march’d to Derby & encamped.”

1 Comment

RSVP Here On June 1, 1778, Christopher Moyer and Philip Huffman escaped from the enemy. They had both been captured at the Battle of Germantown. Now free, they rejoined the 8thVirginia Regiment and continued the fight. The Virginia Convention had intended the 8thVirginia to be a German regiment, recruited on the frontier and led by German field officers: Col. Peter Muhlenberg, Lt. Col. Abraham Bowman and Maj. Peter Helphenstine. The regiment was never purely German, but the lower Shenandoah Valley (where several companies were raised) were indeed heavily German. Moyer and Huffman were from Culpeper County, adjacent to an older settlement of Germans who had come by a different Route: Germanna. Was the 8thVirginia’s Culpeper company, led by Culpeper Minutemen veteran George Slaughter, assigned to the regiment because of the Germanna settlement? Moyer was a Germanna descendent. Hufman was probably not. Slaughter might have been. Gabe Neville will tell the fascinating story of the 8thVirginia and ask “Just how German was it?” in a presentation at the Germanna Foundation’s Hitt Archeology Center on Thursday, September 12, 2019. The event is free and open to the public. From the Foundation: Mr. Gabe Neville will present on George Slaughter, a Captain of the Culpeper company of the 8th Virginia Regiment. The 8th Virginia was originally designated “the German Regiment” by the Virginia Convention. Though the 8th Virginia did not develop into a uniformly German regiment, the Convention’s intent may explain Culpeper’s inclusion in the regiment’s recruitment area and Slaughter’s commission as a captain. He will mention other Culpeper soldiers with Germanna connections and complete their stories by following them into the Tennessee and Kentucky post-war frontiers. Gabe Neville has been researching the history of the Revolutionary War’s 8th Virginia Regiment for more than 20 years. Working toward an eventual published history, he gives speeches, maintains a blog at 8thVirginia.com, and publishes essays on related subjects. He also writes occasionally on public policy issues. A former journalist and congressional staffer, he is now Senior Advisor at Covington & Burling, a Washington-based international law firm. Originally from Pennsylvania, he lives with his family in Fairfax County, Virginia. This event is FREE and open to the public and will take place in the Hitt Archaeology Center, located next to the Fort Germanna Visitor Center. There will be time available for questions after the presentation RSVP Here

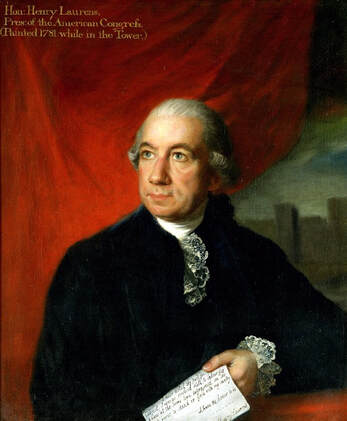

Could the abolition of American slavery have come sooner? Maybe. Slavery never existed in the New World without someone also speaking out against it, and antislavery views took a demonstrably large leap forward during the founding era. Christianity, social contract theory, and the very spirit of the Revolution led many Americans to the same conclusion. Even many slaveowners understood it was wrong. “I can only say,” wrote George Washington about slavery in 1786, “that there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it.” Thomas Jefferson memorably condemned slavery in his first draft of the Declaration of Independence. While this language was removed by Congress, Jefferson really did want to effect a change. His concurrent draft of a Virginia constitution would have decreed, “No person hereafter coming into this country shall be held in slavery under any pretext whatever.” A decade later, he wrote that“The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other. Our children see this, and learn to imitate it; for man is an imitative animal.” His concern was not just for Virginia’s children: And can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are the gift of God? That they are not to be violated but with his wrath? Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep forever: that considering numbers, nature and natural means only, a revolution of the wheel of fortune, an exchange of situation is among possible events: that it may become probable by supernatural interference! The almighty has no attribute which can take side with us in such a contest. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment |

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed