Recovering an Amazing, Never-Told Story.

|

The 8th Virginia Regiment was a unique unit in the Continental Army, and its story has never really been told. Most of its men pointed west, not east, to explain their reason for fighting. They were the sons and grandsons of immigrants from northern Ireland and southwest Germany who fled violence, oppression, and poverty to find freedom and opportunity in America. Economically and socially unable to realize their dreams in the settled east, their families turned to the frontier for land on which to establish communities they could call their own.

"I fought in our Revolutionary War for liberty." |

|

Many of them were Indian fighters. It was Shawnee and Cherokee land, after all, that they wanted. When the King forbade settlement beyond the Allegheny Mountains at the end of the French and Indian War, many of them were more than disappointed. King George denied them the very thing they or their fathers had fought for. The scalping, kidnapping, property destruction, and torture that happened during and after the French and Indian War made many of them feel like they had a score to settle.

|

When the Revolution began, most of them were not fighting over a tax on tea. They were fighting for the right to head west into Kentucky and Ohio. Many of them, in fact, spent more years fighting Indians than they spent fighting Hessians and Redcoats. They were the original pioneers, setting cultural precedents that would later become fixtures in western movies: fringed shirts, long rifles, long migration trails, Conestoga wagons, Indian fighting, dueling, and buffalo hunting (...yes, all of this in Virginia).

"...one of the most perfect battalions of the American Army." To realize their dreams of going west, they first had to fight in the east. Ten companies were recruited during the winter of 1775 and 1776 under Peter Muhlenberg, a 30 year-old pastor from Pennsylvania. Muhlenberg's Woodstock farewell sermon is legendary but weakly documented. Strangely, it has become fodder for the 21st century's culture wars. Some call him a heroic example of Christian civic engagement while others say his story is a fantasy clung to by religious conservatives.

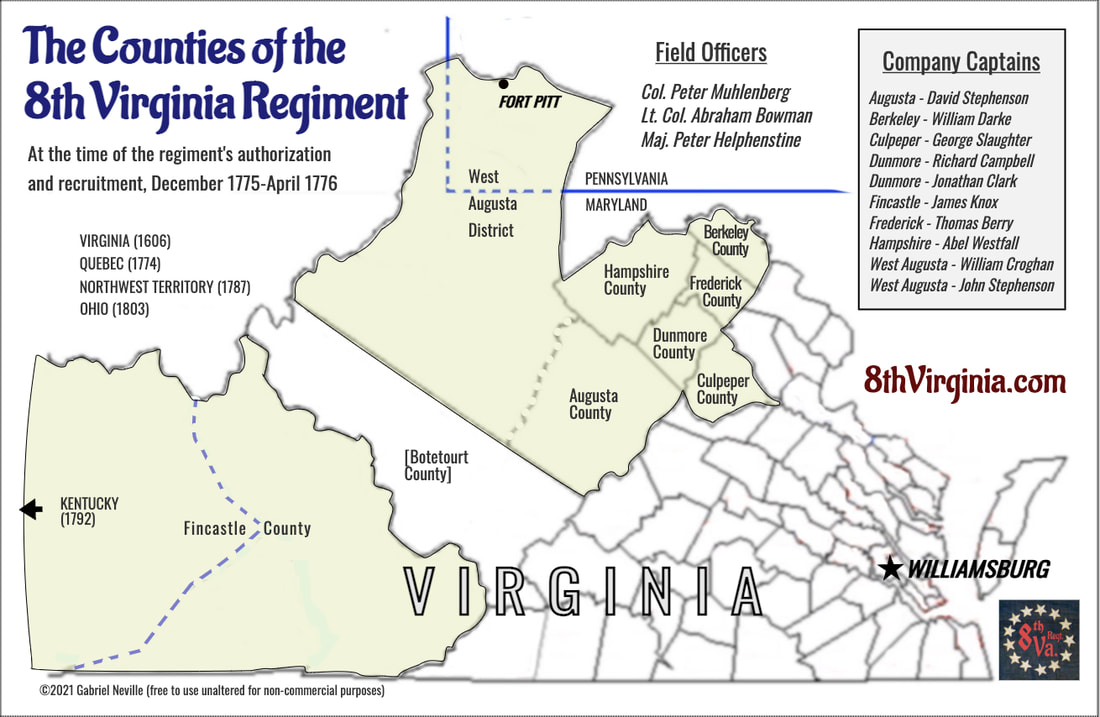

The 8th Virginia was initially intended by the Virginia Convention to be a "German Regiment." It raised several companies in the lower (northern) Shenandoah Valley, to where thousands of Germans had migrated along the Great Wagon Road from Pennsylvania. Culpeper County, on the east side of the Blue Ridge, was also instructed to raise a company. Its Germans had come by a different path. Protestant Irish strongholds in Augusta County, the West Augusta District, and Fincastle County also raised companies. The Virginia Convention's real goal in calling the regiment "German" may have been to ensure that it was German-led. The Irish were regarded as wild, insubordinate, and radical. Their Presbyterianism was synonymous with dissent. Lutheranism, on the other hand, was hardly distinguishable from Anglicanism. The King himself, after all, was German. |

Peter Muhlenberg was the colonel of the regiment and Abraham Bowman the Lt. Colonel. They were from Woodstock and Strasburg in Dunmore (now Shenandoah) County. Peter Helphenstine, of Winchester (Frederick County), was the major. All three were German. Helphenstine had immigrated as an adult. Though the field officers were German, many of the company-level officers were English, Irish, Scottish, Swedish, Welsh, Dutch and maybe Jewish.

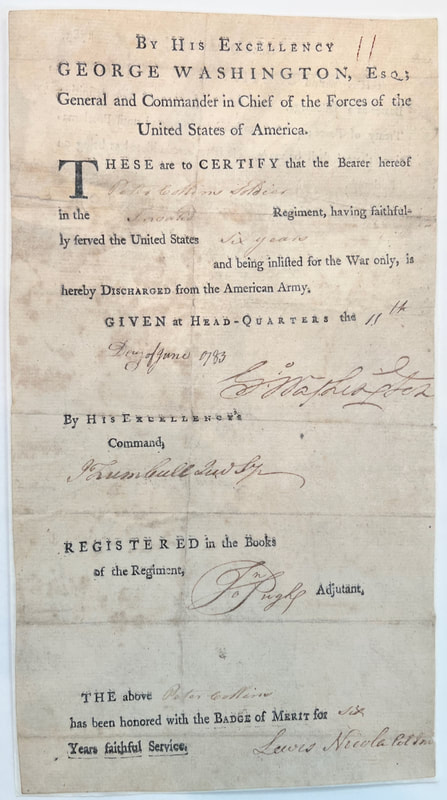

The men who enlisted signed up for two years and came from a vast western territory stretching from the North Carolina line to Pittsburgh (then claimed by Virginia). Their service over those two years was so harsh that only a few dozen of the original 680 enlisted men persevered to the end of their terms when they were discharged at Valley Forge. Frequently divided and detached, they seem to have served everywhere: Charleston, White Plains, Trenton, Princeton, Short Hills, Cooch's Bridge, Brandywine, Saratoga, and Germantown. They shivered through the winter at Valley Forge where they were discharged in the spring. Some reenlisted, but most did not. Many of the original recruits, in fact, were by then dead or severely debilitated from two years of frost-bite, malaria, smallpox, malnourishment, musket balls, bayonets, and imprisonment after capture. A contingent of reenlisted veterans and new recruits served at the Battle of Monmouth before the regiment was folded into the 4th Virginia and ceased to exist. The "8th Virginia" designation was used again, but in reference to a different set of soldiers (the former 12th Virginia). Some of the regiment's best veterans continued to serve in the Continental Army all the way to the end of the war. Others reentered service a militiamen when Cornwallis invaded Virginia in 1781 and helped defeat him at Yorktown.

The men who enlisted signed up for two years and came from a vast western territory stretching from the North Carolina line to Pittsburgh (then claimed by Virginia). Their service over those two years was so harsh that only a few dozen of the original 680 enlisted men persevered to the end of their terms when they were discharged at Valley Forge. Frequently divided and detached, they seem to have served everywhere: Charleston, White Plains, Trenton, Princeton, Short Hills, Cooch's Bridge, Brandywine, Saratoga, and Germantown. They shivered through the winter at Valley Forge where they were discharged in the spring. Some reenlisted, but most did not. Many of the original recruits, in fact, were by then dead or severely debilitated from two years of frost-bite, malaria, smallpox, malnourishment, musket balls, bayonets, and imprisonment after capture. A contingent of reenlisted veterans and new recruits served at the Battle of Monmouth before the regiment was folded into the 4th Virginia and ceased to exist. The "8th Virginia" designation was used again, but in reference to a different set of soldiers (the former 12th Virginia). Some of the regiment's best veterans continued to serve in the Continental Army all the way to the end of the war. Others reentered service a militiamen when Cornwallis invaded Virginia in 1781 and helped defeat him at Yorktown.

|

The Revolutionary War seems distant and hard to relate to for many Americans today. The slavery and powdered hair of America's eastern coastal communities seem like an alien culture now and many of the era's leaders are treated like caricatures of patriotism or racism. The rawness of the 8th Virginia's story is different. In many ways these soldiers were the creators of the pioneer spirit (warts and all) that built the America to come. Yet, their story has never been accurately or completely told. No book-length history of the regiment has ever been written. Muhlenberg, Bowman, and others in the regiment have been celebrated for their accomplishments in statues, biographies, place names, songs, and stained glass windows--but much of that history is wrong, romanticized, overly debunked, or told without enough context to make it meaningful.

|

I've spent years researching this fascinating story. I'm piecing it together like a big jigsaw puzzle. Eventually, I'll share my work. For now, I'm offering parts of the story here. Enjoy!

Gabe Neville

Springfield, Virginia

August 29, 2015

Gabe Neville

Springfield, Virginia

August 29, 2015