Part of the key to the flag's survival is its construction from "unweighted silk." According to RareFlags.com: One of the most luxurious and expensive of all fabrics, the use of silk in American flags is typically reserved for the finest quality flags, most often for military or official use. Several qualities of silk make it an exceptionally good fabric for use in flags. The material is light-weight, exceptionally strong, tightly woven and weathers well. Its shimmering appearance is beautiful and impressive. For military standards, silk allows for large flags that are light and which dry quickly. The fineness of the material allows for the application of painted decorations, as is often seen in the painted stars and decorative cantons of flags produced for wartime use, especially those of the American Civil War. One unfortunate problem with antique silk flags is that large numbers of them, including many Civil War era battle standards, were made of "weighted silk". Sold for centuries by length, merchants shifted from selling silk by length to selling it by weight, beginning in the early 19th century (circa 1820-1830). In order to earn more money for their silk, merchants frequently soaked the silk in water laden with mineral salts. Once dried, the mineral salts remained in the silk fibers and added weight to the silk, thus bringing the merchant more money. Unfortunately, these mineral salts proved to be caustic and caused severe breakdown in the silk fibers over time. Many flags made of weighted silk are very brittle, often deteriorating under their own weight. Yet flags made of unweighted silk, some of which are decades older than later weighted silk flags, remain in a remarkable state of preservation. Thank goodness the dishonest practice of weighting hadn't begun when this flag was made! Read More: "The Grand Division Standard of the 8th Virginia" More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

0 Comments

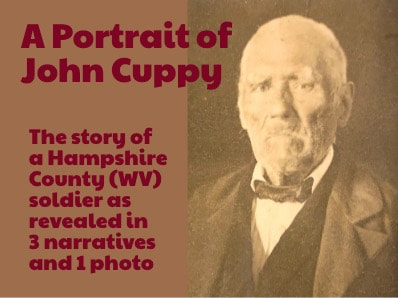

Grant was a soldier in Capt. Michael Bowyer's company of the 12th Virginia Regiment, a regiment that served alongside the 8th Virginia under Brig. Gen. Charles Scott in 1777 and 1778. Bowyer's company was raised in Augusta County, which was also the home of Capt. David Stephenson's 8th Virginia company, Grant's narrative has been important in my work compiling a history of the 8th Virginia. It is only through this record, for instance, that we know Capt. William Darke performed important service under Gen. William Maxwell at Cooch's Bridge and Brandywine. Notably, Grant calls Darke a "Dutchman," apparently assuming he was German because of his connection with the 8th Virginia. Darke wasn't German, but Sgt. Grant evidently didn't have enough direct contact with Darke to know that. The narrative also portrays both of the war's two fronts--the frontier war against the Indians and the eastern war against the British and Hessians. The frontier war is little-remembered today, but was top-of-mind to the men of the 8th and 12th Virginia regiments. The western war was begun by their fathers in the French and Indian War and would not really end until the fall of Tecumseh in the War of 1812. Grant's personal story is unique. He describes his life as a frontier Tory, too afraid to let his true inclinations be known. The narrative does, however, allow for an entirely different interpretation. It could be that he was in fact captured and was merely pretending to be a defector in the hope of getting better treatment. His story seems to be become less reliable the closer it comes to the time of his capture (or defection), at least with regard to his descriptions of American morale and logistics. Whatever his motives were, he was clearly telling the British what they wanted to hear. The entire narrative is transcribed below, with minimal corrections and added paragraph breaks for ease of reading. Sir, About the beginning of July 1776. the Cherokee Indians, excited by a number of the friends to Government, in that place commonly called Tories, who had fled from North Carolina, fell upon the Western frontiers of Virginia; whereupon the Committees of the several Counties detached severall small parties of militia to stop their progress thro’ the Country, untill such time as an army could be raised to oppose them, which at that time was very difficult, as the major part of the youth who were zealous for the cause, were already in the service against the King's troops.

He immediately assembled his new Army at Staunton, a small town in Augusta County, lying about 20 miles to the Westward of the South Mountain, from whence he marched Aug[us]t 18th and proceeded directly to Holstein [Holston], a settlement upon the frontiers where the Indians were then ravaging; but upon the approach of the army retreated with their booty. The Col. finding they would not come to a decisive engagement so far from home, determined to pursue them to their towns, to expedite which he encamped his army on an island formed in the river Holstein, generally known by the name of the Long Island, untill such time as he could be reinforced with provisions and men, upon which there were severall draughts taken out of the Militia[.] General Washington at the same time petitioning for more troops, and a draught of the Militia being granted, it fell to my lot to go as one. At that time I taught a school in Augusta County, but being zealous for government was determined not to go, but finding I was not able to withstand their power, which was very arbitrary in that part, I thought it better to enter into the service against the Indians than to go into actual service against my Countrymen. Accordingly some troops were raising at that time by Act of the Convention of Virginia (to be stationed at the different passes on the Ohio to keep the Shawneese &c in awe and to prevent their incursions) upon these terms, vizt that they should enlist for the term of two years, that they should not be compelled to leave the said frontiers or be entred into the Continental service without their own mutual consent, as also that of the legislator. Taking this to be the only method of scree[n]ing myself from being deemed a Tory and also of preventing my being forced into the Continental service, I enlisted the third of Septemb[e]r into Capt. Michael Bowyers's Company of Riflemen, to be stationed at the mouth of the Little Kennarah [Kanawha] upon the River Ohio. Soon after we marched in company with 150 militia, to the assistance of Coll. Smith, who still continued on the Long Island. We had several skirmishes with the Indians during our march, without any considerable loss on either side. Sept[embe]r 19th we joined the main body, and on the 22d decamped and proceeded towards the Cherokee towns. The enemy continued to harrass us in our march with numberless attacks, sometimes appearing on our front, sometimes upon our flank, so giving us a brisk fire for some minutes, would immediately retreat into the woods. Thus we continued our march thro' the woods the space of three weeks, about which time we received intelligence from our spies and from some prisoners that had escaped, that the Indians had removed every thing from their towns into the mountains, had cut down their corn & set fire to every thing they could not carry away which they thought might be of service to the white army. Upon the confirmation of this account Coll. Smith being persuaded they would never hazard a general engagement, and knowing that his army was but badly supplied with provisions, sent severall companys back into the different Settlements where the Savages were still making incursions and murdring the inhabitants; the Company to which I belonged was one of this number. We were sent to a place lying in the Allegany mountains (upon the banks of the River Monongalia) known by the name of Tygar's [Tygart] Valley where we were ordered during the winter, in order both to defend the Inhabitants and to make canoes to carry us down the river to the place where we were to be stationed the ensuing Spring; in which place I was made Serg' in which I continued during my stay in the army. In the mean time the Indians, finding the Virginians fully bent to search them out and an army of Carolina troops approaching on the other side, sent Deputies to Col. Smith to sue for peace, which was granted upon their delivering up the prisoners, and restoring the goods that they carried out of the Settlements. Hereupon the Militia was disbanded, and the other troops that were enlisted on the aforementioned terms were distributed amongst the frontier settlements during the winter. About this time the war was very hot in the Jerseys, and the Congress determining to recruit their army as soon as possible in the Spring, sent a remonstrance to the Convention of Virginia, alledging that they had a number of troops on their frontiers that were of very little or no service to the country, as the Indians were peacably inclined. Therefore they desired that they should be sent to the assistance of the Continental army as early in the Spring as they possibly could. The Convention immediately repealed the Act on which the troops were raised and directly entered them into the Continental service, and issued forth commissions for the raising of six new Battalions, amongst which the troops formerly raised for the defence of the back frontiers were to be distributed. Agreeable to this new Act we received orders to march to Winchester, there to join the 12th Virga Regt commanded by Col. James Wood; pursuant to which orders we marched from Tygar's Valley in the begining of Aprill and proceeded with all expedition; which march we compleated in the space of eight days; after having rested a few days at Winchester we proceeded to join the Continental Army, which at that time lay partly in Morristown, partly at Boundbrook a small town on the Rarington [Raritan] river about 6 miles from New Brunswick, where His Excellency Generall Howe had his head quarters. May 19th we joined the grand army which then consisted of 20000 foot (chiefly composed of Virginians, Carolinians, and Pennsylvanians, the major part of whom were volunteers, altho’ for the most part disaffected to the rebel cause, they being for the most part convicts and indented servants, who had entered on purpose to get rid of their masters and of consequence of their commanders the first opportunity they can get of deserting) and about 300 light horse commanded by General Washington assisted by Lord Stirling, Major Generalls Stephens, Keyn [?], Sullivan; Brigadiers Weeden, Millenberg [Muhlenberg], Scott, Maxwell, Conway, which latter is a French man. Likewise a number of French officers who commanded in the Artillery, whose names or ranks I never had an opportunity of being acquainted with. Nothing worthy of notice happened untill the 30th of that Inst on which the Continental Army decamped and retreated about 2 miles into the Blue [Watchung] Mountains and incamped at Middle Broock, where they were joined in a few days by the other part of the army that lay at Morristown. Here they lay for some considerable time, during which they were employed in training their troops who were quite undisciplined and ignorant of every military art. Their Officers in general are equally ignorant as the private men, through which means they make but very little progress in learning. Wherefore it is generally believed by the unprejudiced part of the people that the rebells never will hazard a generall engagement, unless they are so hemmed up that they cannot have an opportunity of waving it; from which reason and the deplorable state the Country in generall is now reduced to, which in many places near to the seat of war is entirely destitute of labourers to cultivate the ground, insomuch that the women are necessitated for their own support to lay aside their wonted delicacy and take up the utensils for agriculture. From these and many other weighty reasons it is generally supposed that they cannot continue the war much longer. Nothing material was transacted on either side till about the 24th of June, when a party of General Howe's army made a movement and advanced as far as Somerset, a small town lying on the Rarington betwixt Boundbroock and Princetown, which they plundered, and set fire to two small churches and several farm houses adjacent. General Washington upon receiving notice of their marching, detached 2 Brigades of Virginia troops and the like number of New Eng[lan]d to Pluckhimin, a small town about 10 miles from Somerset, lying on the road to Morristown. Here both parties lay for several days, during which time several slight skirmishes happened with their out scouts, without any considerable loss on either side. On the 29th the enemy retreated to Brunswick with their booty and we to our former ground in the Blue Mountain. Next day His Excellency General Howe marched from Brunswick towards Bonumtown with his whole army, which was harassed on the march by Col. Morgan's Riflemen. As soon as General Howe had evacuated Brunswick, Mr Washington threw a body of the Jersey militia into it, and spread a report that he had forced them to leave it. July 2d there was a detachment of 150 Riflemen chosen from among the Virginia regiments, dispatched under the command of Capt. James [William] Dark a Dutchman, belonging to the eighth Virginia Regt to watch the enemy's motions. The same day this party, of which I was one, marched to Quibbleton [Quibbletown], and from thence proceeded towards [Perth] Amboy. July 4th we had intelligence of the enemy's being encamped within a few miles of Westfield; that night we posted ourselves within a little of their camp and sent an officer with 50 men further on the road as a picquet guard, to prevent our being surprised in the night. Next morning a little before sun rise the British army before we suspected them, were upon pretty close on our picquet before they were discovered, and fired at a negroe lad that was fetching some water for the officer of sd guard, and broke his arm. Upon which he ran to the picquet and alarmed them, affirming at the same time that there was not upwards of sixty men in the party that fired at him. This intelligence was directly sent to us, who prepared as quick as possible to receive them and assist our picquet who was then engaged, in order for which, as we were drawing up our men, an advanced guard of the enemy saluted us with several field pieces, which did no damage. We immediately retreated into the woods from whence we returned them a very brisk fire with our rifles, so continued firing and retreating without any reinforcement till about 10 oClock, they plying us very warmly both with their artillery and small arms all the time; about which time we were reinforced with about 400 Hessians (who had been taken at sea going over to America & immediately entered into the Continental service) and three brass field pieces under the command of Lord Stirling. They drew up immediately in order to defend their field pieces and cover our retreat, and in less than an hour and a half were entirely cut off; scarce sixty of them returned safe out of the field; those who did escape were so scattered over the country that a great number of them could not rejoin the Army for five or six days, whilst the Kings troops marched off in triumph with three brass field pieces and a considerable number of prisoners, having sustained but very little loss on their side.

Generall Howe crossed over in Strattan [Staten] Island, at which time we returned to the Camp with scarce two thirds of the men we took away, where we remained 4 or 5 days, then decamped and marched to Morristown and lay there untill we received certain intelligence that the army had gone on board and stood out to sea bearing to the Northward. Upon this news we instantly decamped and marched toward the North River, and encamped at the Clove, about 12 miles South from King's Ferry, where Generall Sullivan left us with about 5000 men and crossed the Ferry. Soon after we again decamped and proceeded further up the River towards Albany. The weather being excessive rainy we were obliged to halt severall days during which time we rec[eive]d an account of Genl Howe's appearing in the Bay of Delaware, which caused us a very hard and fatiguing march, often marching at the rate of thirty miles per day, which killed a number of the men. It was no uncommon thing for the rear guard to see 10 or 11 men dead on the road in one day occasioned by the insufferable heat and thirst; likewise in almost every town we marched through, their Churches were converted into hospitals. Another great hurt to the army was the scarcity of salt and bread, the former of which was not to be had at any rate, for at that time in the Jerseys it sold for 20 dollars pr bushell: as to the latter they were almost in the same condition, altho’ they had plenty of flour they had not time to bake it. Thus we marched till we came to Germantown a village about 6 miles from Philadelphia, where we encamped for severall days, and we[re] reviewed by the Congress. In the interim the British fleet stood out to sea again and steering to the Northward as at first, we again removed and marched to the Cross roads in Bucks County, about 20 miles to the Northward of Philadelphia, and there we pitched our tents, expecting every day to hear of their landing at York, or in some part of the Jerseys. During our stay here we were joined by the 13th Virga Regt a small body of new raised troops to the amount of about 200. About this the Rebel army was very sickly, occasioned greatly by the scarcity of salt, and the great fatigue they had sustained, during the late hard and fatiguing march; which was soon followed by another as hard tho’ not so long. August 22d we recd an account that Generall Howe had landed in Virginia. Next day we decamped and marched 15 miles towards Philadelphia and prepared to march through the City next day, which we did in the best order our circumstances could permit, and proceeded towards Virginia with all expedition; but received soon after a true account of his being at the head of Elk in Maryland. General Washington, being determined to stop his progress towards Philadelphia, posted a body of millitia at Ironhill an eminence about three miles from General Howe's out posts. He also posted three brigades of Virginians with 6 field pieces at Christian [Christiana] Creek about 8 miles from Wilmington, from each of which they detached a party of 100 light armed men, as scouts, under the command of Col. [William] Crawford. Among this number I had the good fortune of being one, as I was determined to embrace the first opportunity of escaping, which I fortunately effected. General Washington with the remainder of his army (which in whole by his own account only consisted of 13000 men) and the artillary park, which consisted of 15 brass field pieces and severall howitts, encamped at Brandywine Creek about 12 miles from Elktown where General Howe held his head quarters. On Saturday August 30th we received intelligence by some prisoners that General Howe intended to make an attack on Ironhill next day. Accordingly next morning between two and three o'Clock, we marched over the hill, and formed our selves into an ambuscade, in which position we continued till five, when being persuaded that no attack would be made, a party of 150 men was immediately chosen and sent under the command of the aforesd Capt. Dark, to reconnoitre. In this party I went as a volunteer, fully resolved never to return unless as a prisoner. However, marching from thence, took several by roads, untill we had got past several of the Hessians posts undiscovered, and proceeding toward an iron work where they had another post, we discovered a few of the Welch fusileers cooking at a barn in the middle of a large field of Indian Corn. Capt Dark resolved to take them if possible, on which account he divided his men into 6 parties of 25 each, under the command of a Lieu[tenant] and 2 Serjeants. The party on the left to which I belonged, he ordered to surround the field, which we did, but were discovered by those whom we thought to surprise, who were only a few of a party consisting of fifty that were out foraging. They drew up immediately and marched out of the field; upon which our Lieu[tenant] and 4 of his men fired upon them, which they returned with a whole volley, and plyed us very warmly from among the trees for some considerable time, untill the other parties came up and attacked them in the rear; whom they also gallantly repulsed and put to flight. The party I belonged to upon the approach of the rest, retreated; at which time I left them, and made the best of my way to the English Camp. In my way I saw severall of the rebells lying dead, and was afterwards informed that a number more of them fell in that action; which in every probability will be the fate of the whole, if they come to a generall engagement, which of necessity they must in a short time, as it is impossible they can sustain the war much longer; the Country being entirely laid waste, the inhabitants disaffected and entirely wearied of the war, and independency; numbers of them are detained from coming to the Royal Standard only through fear of being detected by General Washington's army, the army small, undisciplined, disaffected to the cause, badly paid, in very dull spirits, being certain they are far inferior to the British troops in every point, and entirely destitute of every necessary for carrying on the war, having neither arms nor ammunition, but what they receive from the French or Dutch. From these and many other cogent reasons it is highly probable this unhappy war will soon be terminated to the honour of His Majesty and a terror to all other who may attempt to rebell in like manner for the future. Thus Sir I have given you a short narrative of the facts that came to my knowledge during my stay in the rebell army, and hope it will give your Honour the satisfaction required. I think myself happy in having the honour of serving you in this manner and of subscribing myself Your most obedient & humble Serv' Ship Queen, Indiaman William Grant. at Gravesend Novr 24th 1777 [Revised 11/23/20] More from The 8th Virginia RegimentAfter the grueling marches to and from Trenton, only a handful of Captain William Croghan’s Pittsburgh men were able to continue on to the Battle of Princeton on January 3, 1777. Princeton was a key American victory. It proved that Trenton wasn’t just a fluke, and it breathed new life into a cause that was just about exhausted. At Williamsburg, the company’s core of about 70 men had been boosted to 140 by the addition of stragglers who had missed the 8th Virginia Regiment’s rendezvous. The company, attached to the 1st Virginia for the year, was at the very center of the action at Trenton, lined up only a few yards from the commander in chief. The marches to and from Trenton were much harder on the men than the battle itself. By the time Washington crossed the Delaware again for another go at the enemy, only a fraction of the men were able to go with him. A mere 20 men from the 1st Virginia were healthy enough to join. Of them, only five can be shown from pension records to have been from Croghan’s detachment from the 8th Virginia —one twenty-third of the original 140. The rest were dead, had deserted, or were sick in camp on the other side of the river. Even Croghan seems to have been absent, leaving Lieutenant Abraham Kirkpatrick in command. Kirkpatrick was a tough, mean, and belligerent man, but also an effective soldier. With him were privates Henry Brock, Harmon Commins, Jonathan Grant, David Williams, and perhaps others who left no record of their presence. All three of the 1st Virginia's field officers were wounded or sick, leaving command to Captain John Fleming. These men, together with the remnants of three other Continental regiments and 200 Pennsylvania state (not Continental) riflemen, were Washington’s advance force, under Brigadier General Hugh Mercer’s command. Fleming’s men went first as they clambering over the icy banks of a ravine and proceeded through an orchard. On the other side of the trees they found fifty dismounted British dragoons lying prone behind a split-rail fence. The dragoons rose and fired a volley. As often happened, this first volley went over their heads—splitting the branches of the fruit trees above them. The dragoons retreated about 40 feet to reload as they were reinforced by a British infantry regiment.

Captain Fleming was killed. His lieutenant, Bartholomew Yeates, was sadistically shot, stabbed, beaten and left to die. Lieutenant Abraham Kirkpatrick was wounded too, but also fortunate enough to be carried off the field by Private Grant. The British captured a cannon, turned it around, and fired it as the Americans ran. Colonel John Haslet of Delaware, attempting to rally the men behind a farm building, was shot through the head and “dropt dead on the spot.” A unit of Philadelphia Associators (militia) arrived to help, but were also quickly forced to retreat. With the Revolution itself hanging in the balance, George Washington brought more reinforcements and daringly risked his own life rallying the troops. “At this moment Washington appeared in front of the American army,” recalled a Pennsylvania state rifleman, “riding toward those of us who were retreating, and exclaimed ‘Parade with us, my brave fellows, there is but a handful of the enemy, and [we] will have them directly.’” The American soldiers were moved, physically and emotionally. “I shall never forget what I felt at Princeton on his account,” wrote one of the Philadelphia Associators, “when I saw him brave all the dangers of the field and his important life hanging as it were by a single hair with a thousand deaths flying around him. Believe me, I thought not of myself.” In the battle that followed, Washington and his men were victorious. After the devastating losses of 1776, Washington had learned to win smaller battles fought on his own terms and to avoid major set-piece battles like those he had lost in New York. Most importantly, his countrymen believed again that they could win. The death of Hugh Mercer, a former commandant of Fort Pitt during the French and Indian War, was widely mourned. Today, eight states have counties named for him and there are countless towns, streets, and schools named in his honor. Unfortunately, the central importance of the battle in which he, Colonel Haslet, Captain Fleming, and Lieutenant Yeates gave their lives is lost on too many people today--including the people who own the ground on which they fought. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment |

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed