More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

0 Comments

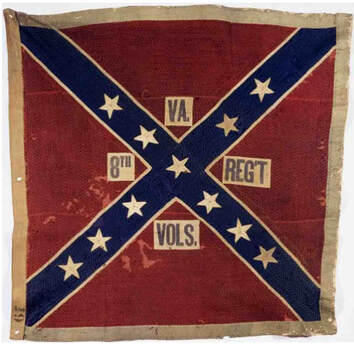

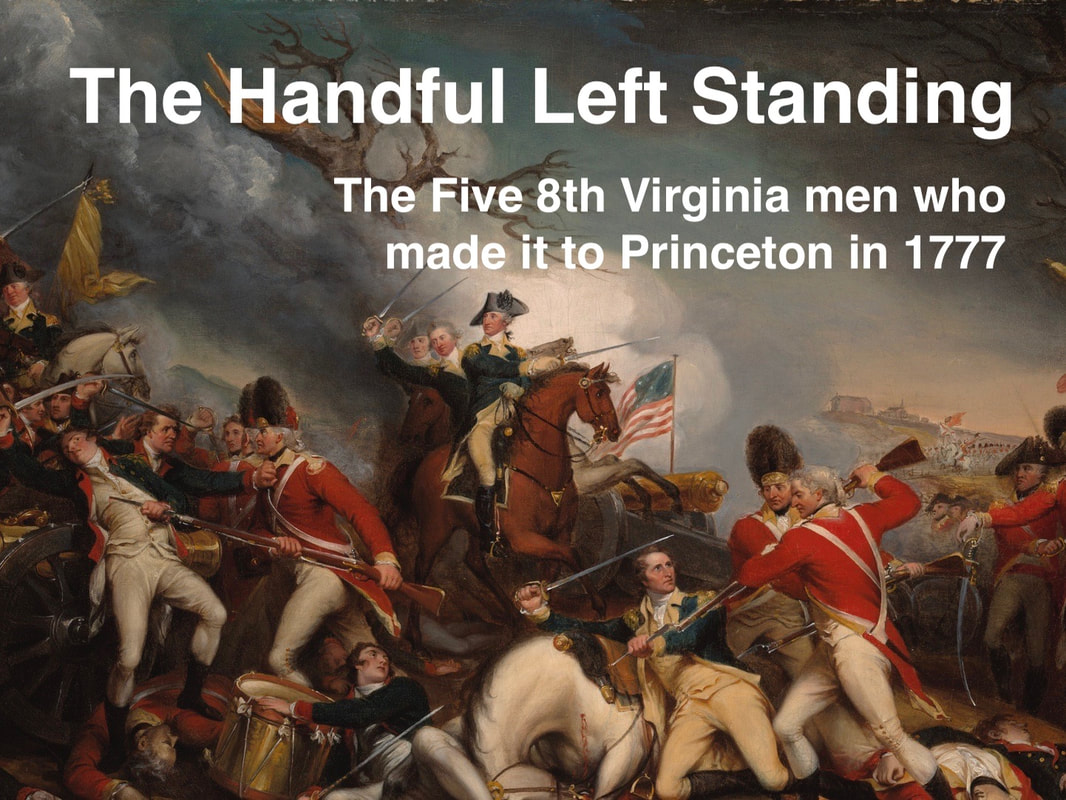

Battle flag of the "Bloody Eighth," also knows as the "Berkeley Regiment." Battle flag of the "Bloody Eighth," also knows as the "Berkeley Regiment." The designation “8th Virginia Regiment” was used three times in two wars for non-militia units: twice in the Revolution and once in the Civil War. The existence of three regiments of the same name sometimes causes confusion for researchers and genealogists. This confusion is exacerbated by the fact that two of them were recruited in overlapping territory and the third was recruited nearby. This post is intended to make it easy to distinguish among them, and to provide a little bit of service history. In the French and Indian War, Virginia had one "Virginia Regiment," notably commanded for part of the war by George Washington. The was (briefly) a 2nd Virginia Regiment, as well. In the Revolution, the Old Dominion had 15 numbered regiments. In the Civil War it had 64. The Original 8th Virginia, 1776-1778

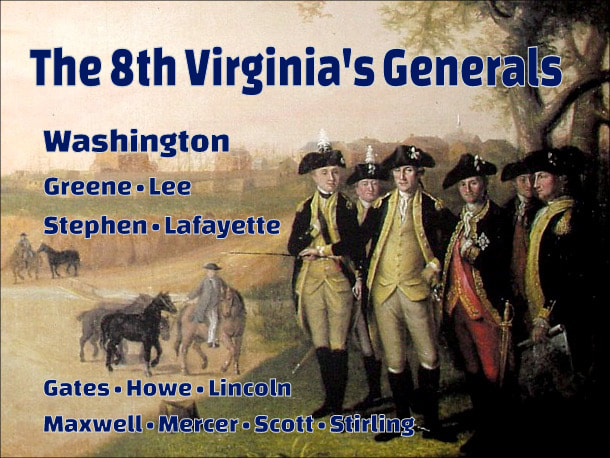

Most of the men in the original regiment signed up for two-year enlistments that ended in the spring of 1778 at Valley Forge. That, combined with casualties and weak recruiting, left the regiment significantly understrength when it marched out of Valley Forge. At the Battle of Monmouth, it was provisionally combined with the 4th and 12th regiments, which were also understrength, as the “4th-8th-12th Virginia Regiment.” The 4th, the 8th, and the 12th had all served together in Charles Scott’s brigade since the spring of 1777. The “New” 8th Virginia of 1778-1779

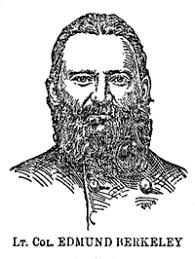

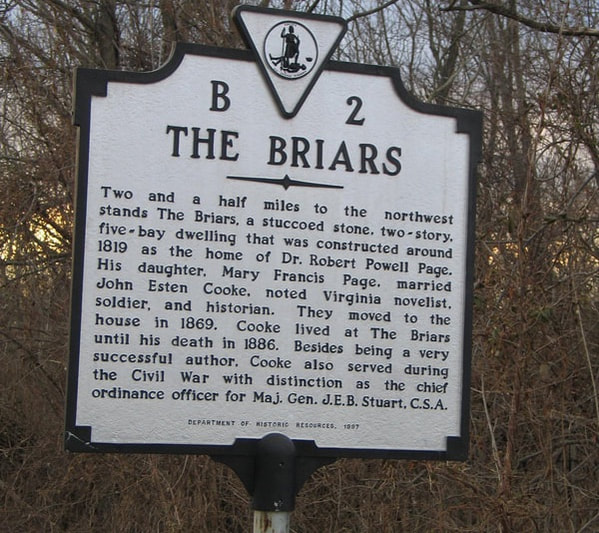

In October of 1777, after Germantown but before the Valley Forge encampment, George Slaughter was promoted to become the new major of the 12th Virginia. He had, up until that time, been a captain in the original 8th Virginia. He resigned in November to deal with a family emergency. In January, he was succeeded by Jonathan Clark, who likewise had until that time been a captain in the original 8th Virginia. When the 12th was redesignated in September of 1778, it’s field officers were Col. John Neville, Lt. Col. Charles Fleming, and Maj. Jonathan Clark. It continued in service until 1779 when the line was reorganized again. The Confederate 8th Virginia Another 8th Virginia Regiment was authorized by the Governor of Virginia in May of 1861 for service in the Confederate Army. It was led by Col. Eppa Hunton, Lt. Col. Charles Tebbs, and Maj. Norborne Berkeley. Major Berkeley was named in honor of Gov. Norborne Berkeley (1718-1770), a popular late-colonial governor. Berkeley, the regiment's best-remembered commander, was a graduate of VMI from Aldie, Loudoun County. Three of his brothers also served as officers in the regiment, leading it to sometimes be called the “Berkeley Regiment.” (It did not recruit in Berkeley County (named for the governor), as is sometimes assumed.) It was also called the “Bloody Eighth” because of its hard service. The Civil War 8th Virginia’s original companies and captains were Company A, the “Hillsboro Border Guards,” raised in Loudoun County and led by N.R. Heaton; Company B, the “Piedmont Rifles,” raised at Rectortown in Fauquier County and led by Richard Carter; Company C, the “Evergreen Guards,” raised in Prince William County and led by Edmund Berkeley; Company D, “Champe’s Rifles,” raised at Haymarket in Prince William County and led by William Berkeley; Company E, “Hampton’s Company,” raised at Philomont in Loudoun County and led by Mandley Hampton; Company F, the “Blue Mountain Boys,” raised at Bloomfield in Loudoun County and led by Alexander Grayson; G Company, “Thrift’s Company,” recruited at Dranesville in Fairfax County and led by James Thrift; H Company, the “Potomac Grays,” raised at Leesburg in Loudoun County and led by Capt. Morris Wampler; Company I, “Simpson’s Company,” raised at Mount Gilead and North Fork in Loudoun County and led by James Simpson, and Company K, “Scott’s Company,” raised in Fauquier County and led by Robert Scott.

In 1905, Edmund Berkeley wrote a poem to welcome Union veterans to a reunion at the Manassas Battlefield that is notable for the grace shown to men who had fired at him on that very field. It was published by the Society of the Army of the Potomac in the report on its fortieth reunion.

O Lord of love, bless thou to-day This meeting of the Blue and Gray. Look down, from Heaven, upon these ones, Their country's tried and faithful sons. As brothers, side by side, they stand, Owning one country and one land. Here, half a century ago, Our brothers' blood with ours did flow; No scanty stream, no stinted tide, These fields it stained from side to side, And now to us is proved most plain, No single drop was shed in vain; But did its destined purpose fill Of carrying out our Master's will, Who did decree, troubles should cease And his chosen land have peace; And to achieve this glorious end We should four years in conflict spend; Which done the world would plainly see Both sides had won a victory. And then this reunited land In the first place would ever stand Of all the nations, far and near, Or East or Western hemisphere. Brothers, to-day in love we've met, Let us all bitterness forget, And with true love and friendship clasp Each worthy hand in fervent grasp And in remembrance of this day Let one and all devoutly pray: That when our earthly course is run And we, our final victory won, Together we'll pass to that blessed shore That ne'er has heard the cannon's roar; And where our angel comrades stand To welcome us to Heaven's bright strand.

The Parrot family were, according to genealogies, among the earliest German-speaking settlers of the Shenandoah Valley in 1734. They are believed to have been Swiss, which would make Jacob and his brothers Joseph and George three of several Swiss-descended soldiers in the 8th Virginia, alongside Chaplain Christian Streit, Lt. Jacob Rinker, and private soldier Joachim Fetzer. The name was originally spelled "Parett" or possibly "Barrett."

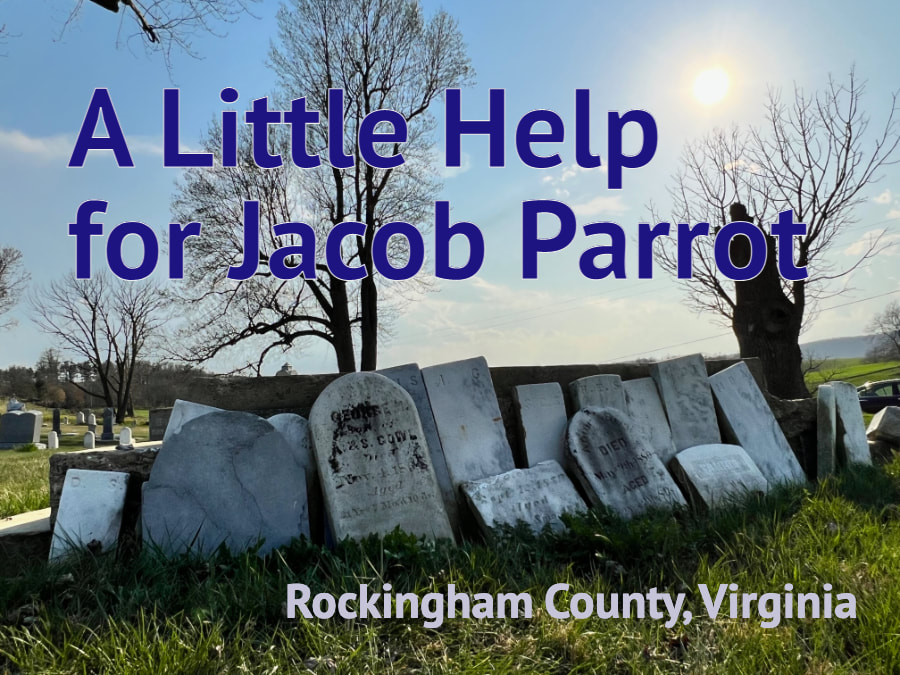

What Lieutenant Parrot did when he "left his detachment" is not clear, though the term "detachment" hints that it happened before the regiment was united in the spring of 1777. A fair guess is that he went home sick from the south without permission. After the ignominious end to his military service, he returned to the Shenandoah Valley and remained there until his death in 1829. He is buried next to his wife in a small cemetery northwest of Harrisonburg, several miles south of his old home in Shenandoah County. Though the stones match, it should be noted that one genealogy states that Jacob was never married.

Pat Kelly lives on the east side of the Blue Ridge in Albemarle County, about thirty miles south of Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and more than an hour southeast of Jacob Parrot’s resting place. He descends from Jacob’s brother John, making him a 7th great-nephew. He grew up in East Tennessee (where his ancestor founded Parrottsville), but moved to Virginia in 1978 when he retired from the Navy. He has several Revolutionary War ancestors and has been researching Henry to see if he also fought in the war. Henry is listed in the Capt. John Tipton's company of activated Dunmore County Militia during Lord Dunmore’s War (1774), but he was not in the 8th Virginia and further service has not yet been demonstrated.

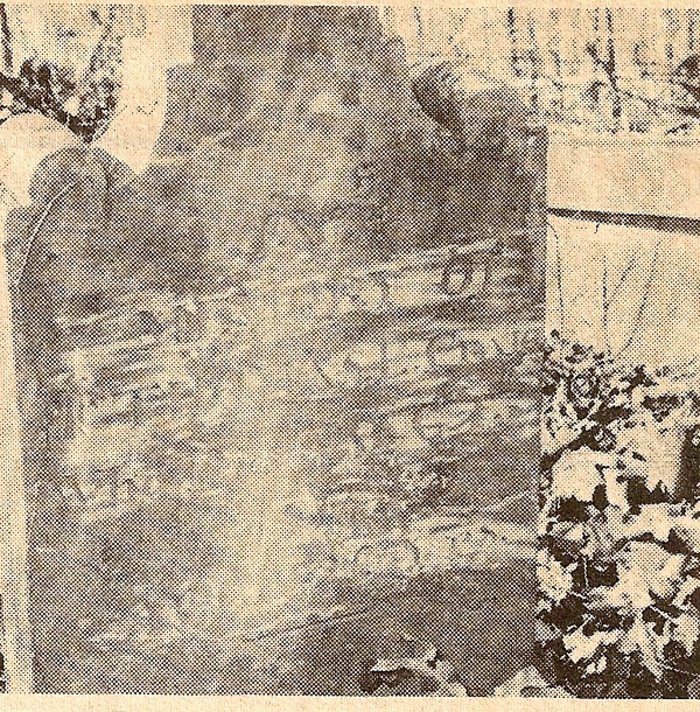

Fortunately, a search of the cemetery found his marker leaning with more than a dozen others against a concrete riser off to the side of the cemetery and not visible from the other graves. It is severely eroded, but its inscription is intact. It is broken at its base and could not be placed back in the ground in its current state. The stone for Jacob’s wife, Rachel, is still in the ground and is of identical design. Though intact, Jacob’s and Rachel’s inscriptions are too eroded to be easily legible. Only a few letters can be made out in photographs taken of them in 2013. Pouring water on Jacob’s stone made it only slightly more legible. The full inscription therefore seemed to be lost before a trick of nature revealed the full wording. Very carefully turning the stone to obliquely face the light of the late afternoon sun illuminated the edges of the letters and brought them back to almost full visibility. It reads TO THE MEMORY OF JACOB PArrIT Departed this Life May th[e?] 12 1829 Age[d?] [7?]2 Years 6 mo 19 d[ays?] The letters are carefully and somewhat formally executed, the odd mix of capital letters, the variant spelling of "Parrit," the small capital “H” in the second word, and the off-center placement of the fourth and fifth lines indicate that the marker was not made by a professional stone carver. If anything, this makes the memorial even more valuable as a relic of Jacob Parrot’s life. Someone who dearly loved him and his wife appears to have worked the stones to honor them. What at first look like scratches near the top of Jacob’s marker seem on closer inspection to be a decoration of some kind, perhaps a flower.

In Parrot’s case, it may be possible to craft a facsimile of the original stone. Then he and Rachel could continue to have matching stones as they have for two centuries. A repaired original could be reset upright at the correct angle to catch the rays of the late-day sun. Or it could be taken to the Harrisonburg-Rockingham Historical Society’s museum. At all costs, it should not disappear into someone’s garage. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

Cooper was the lieutenant commandant, or “captain lieutenant,” of Col. John Neville’s company of the 4th Virginia Regiment. This was a new rank for the Continental Army modeled on British practice that resulted from a cost-saving reduction in the number of officers. As the regiment’s senior lieutenant, Cooper led a company nominally under the direct command of the colonel. Perhaps Abraham Kirkpatrick, the man who shot him, thought Cooper was putting on airs. Whatever his reason, Kirkpatrick was clearly the aggressor. He attacked Cooper with a stick. Cooper apparently had a more peaceful temperament and showed no “disposition to demand satisfaction.” The era’s code of honor, however, required him to make the challenge. His peers could not abide Cooper’s reluctance to stand up for himself and told him that “unless he did, he must leave the Regiment, as they were Determined he should not rank as an Officer.” Cooper reluctantly complied. He and Kirkpatrick faced off with pistols and the hapless lieutenant took a ball of lead to his leg. The limb was amputated and he was transferred to the Corps of Invalids. He was one of the very last men discharged from the army at the end of the war. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

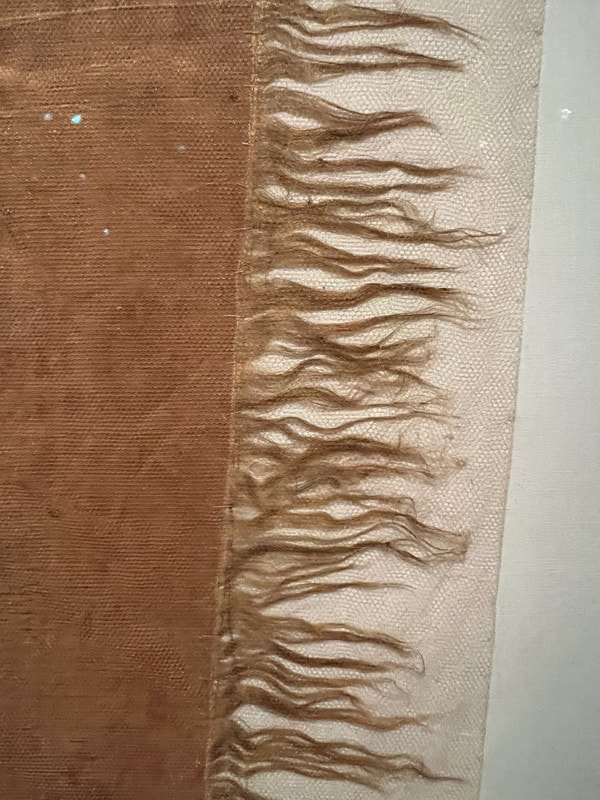

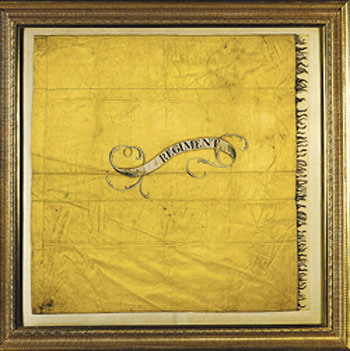

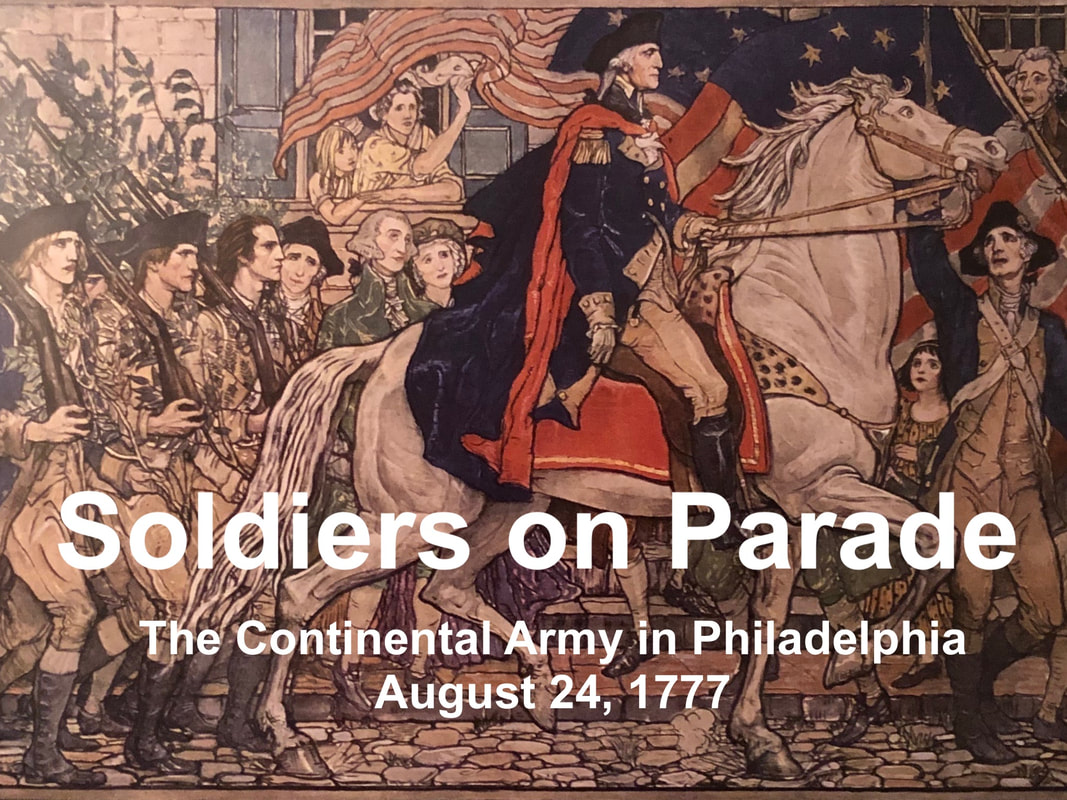

While the Grand Union flag and the Stars and Stripes may have appeared on some battlefields, they were more likely to be seen on forts and ships. Virginia had no state flag until the Civil War. Every regiment, however, had a flag that served important symbolic and battlefield purposes. Regimental flags were unique works of art, often featuring symbols from antiquity or popular culture with mottos in English or Latin. The flags of the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment and Connecticut’s 2nd Continental Light Dragoons are among the very few that survive. There is, however, an 8th Virginia flag that still exists—but it is not the regimental banner. It is a “grand division standard,” one of two that were used to direct halves of the regiment on the battlefield. These were utilitarian devices with little ornamentation. The most important thing about them was their color.

Henry A. Muhlenberg was at that time preparing to publish a biography of his great uncle, the still-useful (but occasionally inaccurate) Life of Major-General Peter Muhlenberg of the Revolutionary Army. The younger Muhlenberg was a member of Congress and quite knowledgeable about his pedigree, but his description of the flag as “the regimental color” was wrong.

"In 2012, the flag was sold at Freeman’s Auction in Philadelphia. Prior to the auction, Freeman’s brought it to Shenandoah County to be displayed. I was lucky that I found out about it just a couple of days prior to the event. I contacted my friend Erik [Dorman] who also was interested in writing about the 8th and we decided to show up in our uniforms. We caused quite a stir when we walked around the corner of the Courthouse into the square. We were immediately enlisted to "guard" the flag and unveil it during the event.”

With it were two smaller, plainer flags of identical design but different colors. The 3rd Detachment was an ad hoc unit cobbled together under Col. Abraham Buford in 1780 from new recruits and soldiers who had avoided capture at Charleston earlier that year. The flags were used at the Waxhaws in South Carolina on May 29 when Tarlton defeated Buford there. It is unlikely that the flags were made specifically for the detachment. The regimental flag is described in detail in a 1778 inventory of then-new flags known as the “Gostelowe Return.” The flags were probably, therefore, inherited from a regiment that was folded into Buford’s detachment. Buford had been colonel of the 11th Virginia, and a number of the men in his detachment were reportedly from the 2nd Virginia. The flag could have come from either of those, or from another. The two “grand division” flags from the Buford detachment are almost identical, except for their colors, to the Muhlenberg flag. Buford’s maneuvering flags are blue and yellow. The Muhlenberg flag is a beige color today and was described as a “salmon” color in 1847. A fabric expert advises that the original color was red. The flag has faded considerably just from its time in the frame. It is not hard to imagine it having faded from red to a salmon color over the century or so before it put under glass. The scrolls on the blue and yellow flags contain only the word "regiment." The word is not centered in the scroll, suggesting that a space was retained to the left on both flags to be filled in when they were assigned to a specific regiment. The writing in the 8th Virginia's scroll is illegible now. It was retouched on one side by Mr. Goetz or a previous owner to say "VIII Virg Regt." The 1847 account in the Richmond Whig says the scroll was styled a bit differently as "VIII Virga Regt."

More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

James Kay enlisted in the 8th Virginia on February 20, 1776. This was four days after someone named John Kay enlisted in the same company. Recruiting and enlisting were family and community affairs in those days. John may have enlisted and then talked James into joining him. John was promoted to sergeant and then became an officer, so he was almost certainly older—probably James’s brother, but maybe his father, an uncle, or a cousin. James was only seventeen.

Captain Berry grew up in King George, at the family plantation known as Berry Plain. Like so many others, his great grandfather had come to Virginia in 1650 as an indentured servant. From that humble start, the family did well. Berry Plain was built about 1720. Thomas and his older brother Benjamin moved to Frederick County sometime before the war and settled near Battletown, the tavern village famous for street brawls sometimes featuring future general Daniel Morgan. Berry Plain is still standing, has been restored, and was up for sale in 2007. (Some of the plantation’s valuable and ancient boxwoods were sold to Colonial Williamsburg in the 1930s, providing much needed funds to “save the farm.”) Battletown, meanwhile, is now known as Berryville and is the county seat of Clarke County (created in 1836). Benjamin is recognized at the town's founder. When Berry and Jolliffe were appointed by the Frederick County Committee of Safety, they had recruiting quotas to fill. It appears that Berry's ties to King George County were still so strong that he made a trip home to recruit among his old friends and neighbors. That, at any rate, would explain Kay’s enlistment. Berry’s company was assigned to the 8th Virginia Regiment, which was brought south into the Carolinas in the spring of 1776. Berry and Kay were present in Charleston for the Battle of Sullivan’s Island, though most 8th Virginia men were not in combat. We know Private Kay was at Sunbury, Georgia that summer when many of his comrades succumbed to malaria. Having grown up near the Chesapeake, he may have had some resistance to the mosquito-borne disease. The soldiers were given furloughs after returning to Virginia that winter and then marched to Philadelphia where they were inoculated for smallpox. Lieutenant Jolliffe was quarantined with smallpox that spring in Winchester, either naturally contracted or from inoculation, and died from it.)

After the war, thousands of Virginia veterans moved to Kentucky. Kay settled in Fayette County, named for the Marquis de Lafayette. By 1826 he lived in Boone County, named for Daniel Boone, but since Boone had originally been part of Fayette that doesn't necessarily mean he moved. He applied for a veteran’s pension in 1833 to supplement a wounded veteran’s benefit he was already receiving and died soon after. He was buried at Salem Baptist Church, then a log church built by a congregation formed in 1827. The church has since been known as Salem Predestinarian Baptist Church and as Salem Creek United Baptist Church.

They found Private Kay’s marker intact but lying flat on the ground in the Salem Baptist Church cemetery. Because the stone is worn and hard to read, they plan to replace it with a new one. The ground is frozen, however, so they are leaving it alone until after the ground thaws. For now, they are working on the application for a government-issued headstone and searching for relatives who might attend a ceremony this summer or fall. If you are a descendant or relative of James Kay, please reach out to the Simon Kenon Chapter, SAR.

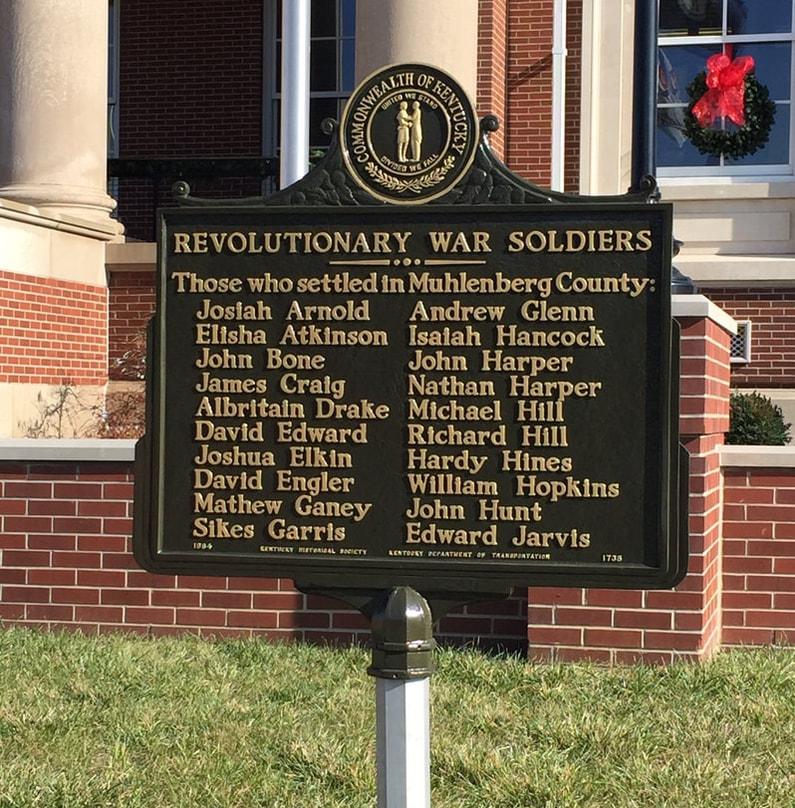

More from The 8th Virginia RegimentGOOD NEWS: As reported in the comment below by Gary Tunget, the Findagrave.com images that formed the basis for this post were are inaccurate. "The Muhlenburg County History group visited the Craig Cemetery This afternoon March 27th with the property owners and two members of the SAR the photo above is not the Craig Cemetery Capt. Craig's grave stone is still standing. and not trampled by cattle . The group is going to clean the cemetery and fence the property and afterwards the Local DAR and SAR will host a Patriot Grave marking ceremony." Apologies are due, particularly to the property owner, for repeating bad information. The Findagrave.com page appears to have been corrected. --Gabe Neville James Craig deserves better. He was a Continental officer who signed on early for the Revolutionary cause and took part in its first major victory. Despite this important service to his country his grave site is now a shambles. Even before there were any Virginia Continental regiments, Craig signed on to help lead one of the Old Dominion’s independent frontier companies. He was a lieutenant under Capt. William Russell in a company that ranged the southwest Virginia frontier from 1775 to 1776. In 1776 he joined Capt. James Knox in forming a Fincastle County company assigned to the 8th Virginia Regiment. After a year serving in the south, he and Knox were selected to lead a company in Daniel Morgan’s elite rifle battalion. With Morgan and Knox, he played a key role in the defeat of Gen. John Burgoyne at Saratoga—the first major American victory and the event that persuaded the French to openly support the cause. After the war Craig settled in Kentucky like thousands of other veterans. He was appointed by the Commonwealth to be one of the first justices of Muhlenberg County, when it was created in 1799. The county, of course, was named in honor of Peter Muhlenberg, under whom Craig had served in the war. Though never famous on the national stage, Craig led a consequential and locally important life. He died in 1816 at the age of 81 after marrying twice and having many children. He is buried in Craig Cemetery in Rosewood, a rural Muhlenberg County community about forty miles west of Bowling Green. According to a Find-a-Grave page maintained by Liz Gossett, Craig’s headstone is in “very bad shape.” The featured image of it appears to be an old one taken from a newspaper. Three pictures of the Cemetery show a progressive decline. The first image, said to be from the late 19th century, shows a tidy, well-kept site. The second, from 2004, shows fallen headstones interspersed with clumps of weeds. A third photo (the first one shown above) shows cattle roaming among the fallen markers, the dirt churned up by their hooves. Ms. Gossett indicates that the cemetery was maintained by descendant Luther Craig until his death in 1960 and has since been abandoned. Someone—the DAR, the SAR, the property owner, or descendants—should restore this cemetery and see to it that James Craig and those buried around him can rest with the dignity they deserve. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

Philadelphia's recently defaced Tomb of the Unknown Soldier is not a memorial for George Washington (though it is located in Washington Square). It is a memorial for the two or maybe three thousand penniless soldiers who are buried there in mass graves. Each was fighting for freedom at a time when a better understanding of freedom and equality was only just dawning on humanity. The evident majority who died of smallpox suffered more than most modern people can comprehend. They died for the principle that "all men are created equal" (the Declaration of Independence, written in 1776) and so that we might have the right "peaceably to assemble" and to "petition the Government for redress of grievances" (the 1st Amendment, written in 1791). "Black lives matter" has essentially the same meaning as "all men are created equal." Both are true statements. The newer slogan, however, is also a Declaration that the "arc of history" has farther to bend until it achieves justice. That is also true. Ask any member of "Mother Emanuel" AME Church in Charleston or the families of Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd. We have a better understanding of freedom and equality today than America's founding generation had. But you have to walk before you can run, and the men buried in Washington Square were among the very first common people on Earth to walk upright and proudly in defense of human and civil rights. Today, most of the world is still trying to catch up. We can't let up now, however. We have farther to go. Read More: "The Tragedy of Henry Laurens" (August 1, 2019) More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

William Croghan has never been famous, but his life illustrates the aspirations and achievements of America’s early frontiersmen. He fought for national expansion and then played an important role in that expansion by moving to Kentucky and running the office that parceled out bounty land to veterans. This was a lucrative position. Croghan prospered and built a stately home, which he called Locust Grove. ...continue to The Journal of the American Revolution. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

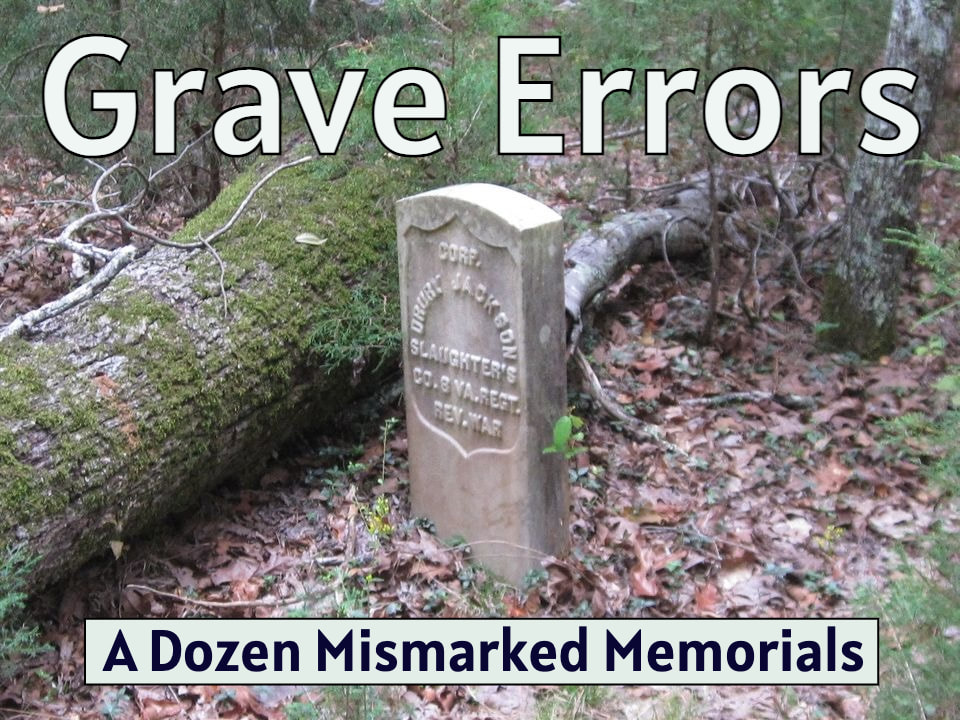

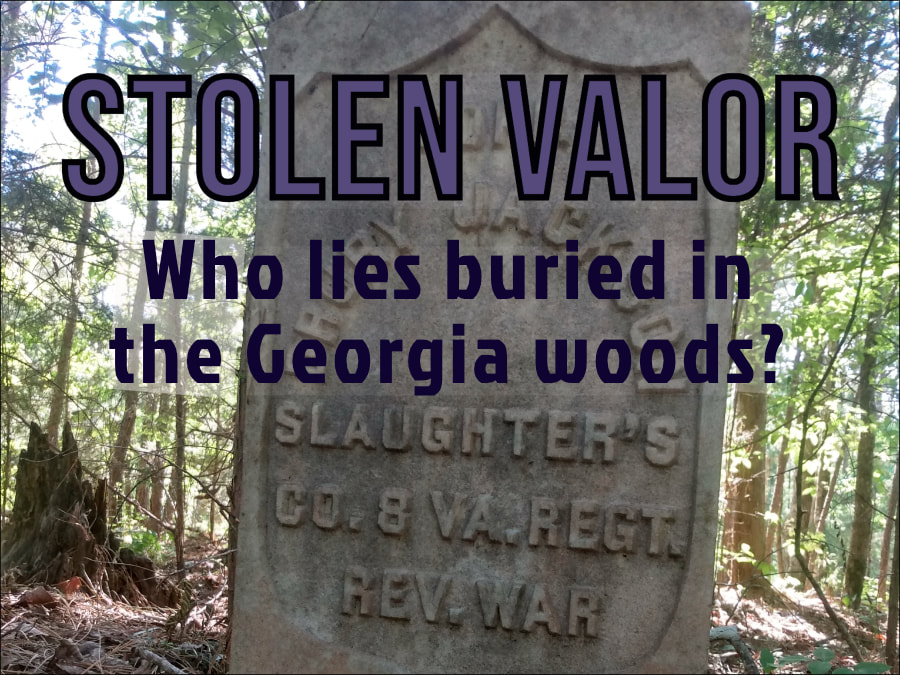

Time changes things. Neither the lake nor the woods were there when Drury Jackson died. Back then the grave was on cleared ground overlooking the Oconee River. Depressions in the soil still reveal to the trained eye that Drury was buried in proper cemetery. The river became a lake in 1953 when it was dammed up to create a 45,000-kilowatt hydroelectric generating station. When Dutch found the grave, the cemetery had been neglected and reclaimed by nature. Today it is in a copse of trees surrounded by vacation homes. Dutch spends his free time studying local history and conducting archeology. He has made some important finds, including a string of frontier forts along what was once the “far” side of the Oconee. He’s pretty sure that Drury’s burial in that spot is an important clue to his life in the years following the Revolutionary War. From there, however, things get complicated. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment |

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed