Morgan accepted to assignment and set about trying to raise three troops of light cavalry. He appointed a trio of men to lead and recruit, and sent letters himself urging local leaders to help. He wrote to Taverner Beale, a former 8th Virginia officer and now a local official in Shenandoah County. "Colo. Triplett I have appointed to raise a Brigade below the Ridge in Fauquier and Loudon," he wrote, " Colo. Darke in Berkeley and Hampshire, Colo Smith in Frederick and Shendooe, will you undertake to raise what men you can in your County and join Colo. Smith[?] The matter is just this, if we do not make head and oppose the enemy they will destroy us." Below is a letter written by General Morgan on June 26th to Virginia's new governor, Thomas Nelson. Nelson had just written him urging him to hurry up. The original is in the collection of Haverford College. It is transcribed without alteration but annotated at the end of each paragraph in italic text. Daniel Morgan to Thomas Nelson, June 26, 1781Sir, I recd the letter you did me the honor to write me by Colo Rootes and in compliance therewith shall March with what Volunteers I have in a day or two. I flatter my self you, Sir, will not think my time has been mispent, when I asure You I have been exerting every nerve to get Men into the field who would be of service when there. ◊ "Colo Rootes" may be George Rootes, who represented Frederick County in the First Virginia Convention in 1776. Nelson succeeded Jefferson as governor on June 12th. He wrote to Morgan from Staunton (where the state government had retreated). You, Sir, are well acquainted with the Enemy’s superiority in Cavalry and the absolute necesity there is for as many horse as We can mount; this has induced me to endeavour to raise three troops mounted on the best horses these Counties can produce; such a reasonable supply will be of the utmost consequence, and their remaining three months will give time for a more permanent establishing of Dragoons, the part of an army not to be dispensed with; to attain this desirable purpose, my self with a number of other Gentlemen, have engaged our selves to some people in Frederick Town in Maryland, for such accoutrements as could be hastily furnished, for payment whereof, we make no doubt, provision will be made, when the accounts are rendered; such necessaries are allways greatly wanted, and when the volunteers times have expired, they will remain to equip future Dragoons; The horses will be an acquisition, the Country will find very beneficial. ◊ This appears to be the point of contention between Morgan and the governor. Morgan had invested time and effort into raising cavalry, but Nelson wanted men of any sort to come as soon as possible. You can’t conceive how reluctantly the people leave their homes at this season of the year, and it was the general opinion if I left the Country before they were imbodied, they would not be prevailed upon to March; small parties have been pushed on and a few days, will produce the wished for march of the whole. ◊ Wheat, grown as what is now sometimes called "winter wheat," was planted in the fall and harvested in June and July. After Saratoga and especially Cowpens, Morgan was a hero. The legislature was counting on his reputation and charisma to inspire men to enlist. Give me leave to press the forming magazines at the places mentioned in my last, from whence the army may be supplyd without delay: and I am of opinion too many workmen can not be imployd in making and repairing warlike instruments—many hands may be set at work in this part of the Country. For want of storehouses we are obliged to pick up provisions in such quantities as it can be found, this frequently subjects us to scantiness and is very disgusting to the people, both which, I humbly apprehend, may be obviated by the recommended magazines. I shall immediately march my voluntiers and what Militia are ready, the remainder will follow with the greatest dispatch. ◊ Morgan is being argumentative here. In the close of Nelson's June 20 letter to Morgan, he explicitly said they had no time for devising complex supply schemes, but indicated they might turn to Morgan's ideas later. Had I known my presence in the Army was so immediately expected, I would have joined it on the earliest notice, but I had gone too far in the Voluntier s[c]heme to recede; it was and still is my opinion they will be extremly usefull—many of the officers I have appointed, have seen service, and the rest, Gentlemen who may be depended on. However sanguine some Gentlemen may be in a hasty gathering of the Militia, You, Sir, who have seen service know, so well an appointed Army as the Brittish, Commanded by so experienced an officer as Lord Cornwallis, is not to be beaten but by well furnished troops, especialy with proper arms and well equipped horse. Could I have properly completed my Volunteer corps of two thousand, I flatter my self we should have done honor to our selves, and distinguished services to our Country. ◊ Morgan is apparently inoculating himself from blame, implying that if his recruits did not perform well, insufficient time to recruit, equip, and train them would be the cause. Morgan joined General Lafayette with the men he was able to raise on July 7th, the day after the Battle of Green Spring. He was unable to continue more than a few days and returned home. I have the honor to be Sir Your most obedt hum Servt 26th June 1781 Danl Morgan More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

0 Comments

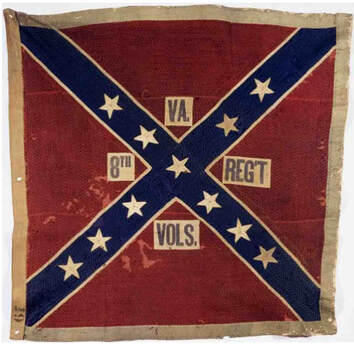

More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

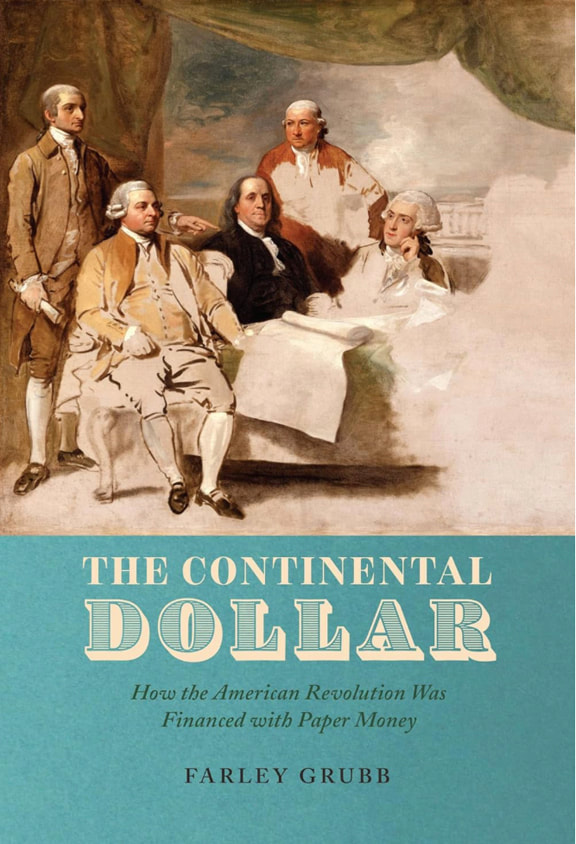

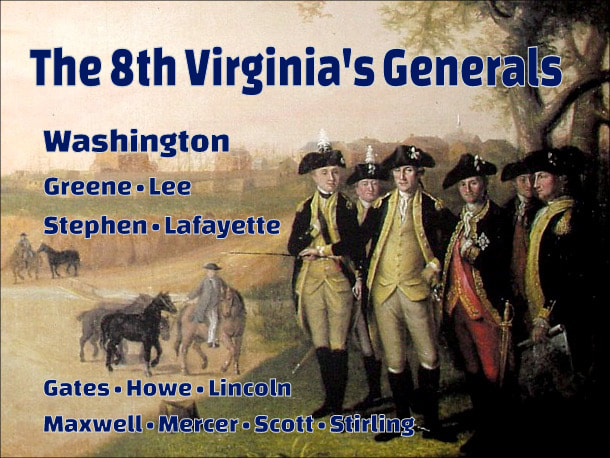

Farley Grubb, an economics professor at the University of Delaware, used the pandemic to complete his quest to set the record straight on Continental currency. “For 230 years,” he writes, “traditional historiography has told us that the Continental dollar was a fiat currency — an unbacked paper money.” We have been told, “Congress printed and spent an excessive number of these paper dollars from 1775 through 1780,” driving their value almost to nothing and producing the phrase, “Not worth a Continental.” The old story is appealing in its simplicity, he concedes, but also requires us to believe the Founding Fathers were “either crazy, deceptive, ignorant, evil, or stupid.” Moreover, the old story falls apart under close examination (page 6-7). Grubb’s book, The Continental Dollar: How the American Revolution Was Financed with Paper Money, is an interesting and valuable contribution to our understanding the Revolutionary War. It is an academic work that includes mathematical formulas that will make many readers’ eyes glaze over, but the vast majority of it is easily understood. It should be required reading for any author tempted to repeat the timeworn accusation that the states and Congress refused to give the Continental Army the support it needed. At least when it came to financing, Congress bled itself dry and pushed the states beyond the limit of what they could possibly do. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment Battle flag of the "Bloody Eighth," also knows as the "Berkeley Regiment." Battle flag of the "Bloody Eighth," also knows as the "Berkeley Regiment." The designation “8th Virginia Regiment” was used three times in two wars for non-militia units: twice in the Revolution and once in the Civil War. The existence of three regiments of the same name sometimes causes confusion for researchers and genealogists. This confusion is exacerbated by the fact that two of them were recruited in overlapping territory and the third was recruited nearby. This post is intended to make it easy to distinguish among them, and to provide a little bit of service history. In the French and Indian War, Virginia had one "Virginia Regiment," notably commanded for part of the war by George Washington. The was (briefly) a 2nd Virginia Regiment, as well. In the Revolution, the Old Dominion had 15 numbered regiments. In the Civil War it had 64. The Original 8th Virginia, 1776-1778

Most of the men in the original regiment signed up for two-year enlistments that ended in the spring of 1778 at Valley Forge. That, combined with casualties and weak recruiting, left the regiment significantly understrength when it marched out of Valley Forge. At the Battle of Monmouth, it was provisionally combined with the 4th and 12th regiments, which were also understrength, as the “4th-8th-12th Virginia Regiment.” The 4th, the 8th, and the 12th had all served together in Charles Scott’s brigade since the spring of 1777. The “New” 8th Virginia of 1778-1779

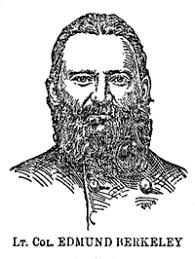

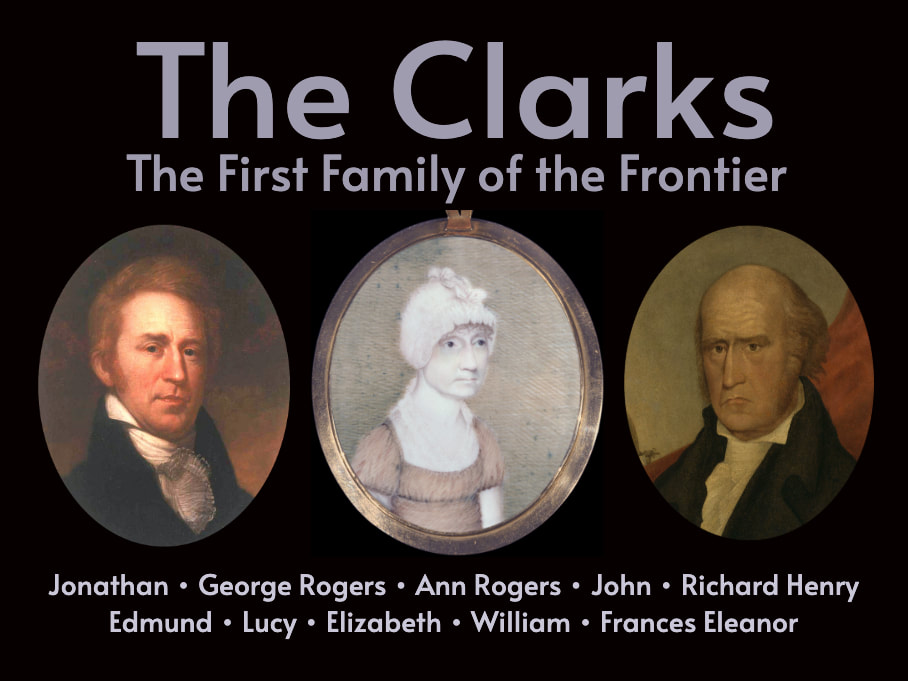

In October of 1777, after Germantown but before the Valley Forge encampment, George Slaughter was promoted to become the new major of the 12th Virginia. He had, up until that time, been a captain in the original 8th Virginia. He resigned in November to deal with a family emergency. In January, he was succeeded by Jonathan Clark, who likewise had until that time been a captain in the original 8th Virginia. When the 12th was redesignated in September of 1778, it’s field officers were Col. John Neville, Lt. Col. Charles Fleming, and Maj. Jonathan Clark. It continued in service until 1779 when the line was reorganized again. The Confederate 8th Virginia Another 8th Virginia Regiment was authorized by the Governor of Virginia in May of 1861 for service in the Confederate Army. It was led by Col. Eppa Hunton, Lt. Col. Charles Tebbs, and Maj. Norborne Berkeley. Major Berkeley was named in honor of Gov. Norborne Berkeley (1718-1770), a popular late-colonial governor. Berkeley, the regiment's best-remembered commander, was a graduate of VMI from Aldie, Loudoun County. Three of his brothers also served as officers in the regiment, leading it to sometimes be called the “Berkeley Regiment.” (It did not recruit in Berkeley County (named for the governor), as is sometimes assumed.) It was also called the “Bloody Eighth” because of its hard service. The Civil War 8th Virginia’s original companies and captains were Company A, the “Hillsboro Border Guards,” raised in Loudoun County and led by N.R. Heaton; Company B, the “Piedmont Rifles,” raised at Rectortown in Fauquier County and led by Richard Carter; Company C, the “Evergreen Guards,” raised in Prince William County and led by Edmund Berkeley; Company D, “Champe’s Rifles,” raised at Haymarket in Prince William County and led by William Berkeley; Company E, “Hampton’s Company,” raised at Philomont in Loudoun County and led by Mandley Hampton; Company F, the “Blue Mountain Boys,” raised at Bloomfield in Loudoun County and led by Alexander Grayson; G Company, “Thrift’s Company,” recruited at Dranesville in Fairfax County and led by James Thrift; H Company, the “Potomac Grays,” raised at Leesburg in Loudoun County and led by Capt. Morris Wampler; Company I, “Simpson’s Company,” raised at Mount Gilead and North Fork in Loudoun County and led by James Simpson, and Company K, “Scott’s Company,” raised in Fauquier County and led by Robert Scott.

In 1905, Edmund Berkeley wrote a poem to welcome Union veterans to a reunion at the Manassas Battlefield that is notable for the grace shown to men who had fired at him on that very field. It was published by the Society of the Army of the Potomac in the report on its fortieth reunion.

O Lord of love, bless thou to-day This meeting of the Blue and Gray. Look down, from Heaven, upon these ones, Their country's tried and faithful sons. As brothers, side by side, they stand, Owning one country and one land. Here, half a century ago, Our brothers' blood with ours did flow; No scanty stream, no stinted tide, These fields it stained from side to side, And now to us is proved most plain, No single drop was shed in vain; But did its destined purpose fill Of carrying out our Master's will, Who did decree, troubles should cease And his chosen land have peace; And to achieve this glorious end We should four years in conflict spend; Which done the world would plainly see Both sides had won a victory. And then this reunited land In the first place would ever stand Of all the nations, far and near, Or East or Western hemisphere. Brothers, to-day in love we've met, Let us all bitterness forget, And with true love and friendship clasp Each worthy hand in fervent grasp And in remembrance of this day Let one and all devoutly pray: That when our earthly course is run And we, our final victory won, Together we'll pass to that blessed shore That ne'er has heard the cannon's roar; And where our angel comrades stand To welcome us to Heaven's bright strand.

Battlefields and Historic Sites

History

Living History Units

Museums and Historical Societies

Patriotic Societies Society of the Cincinatti Daughters of the American Revolution

Sons of the Revolution

Sons of the American Revolution

Reference

Reference and General

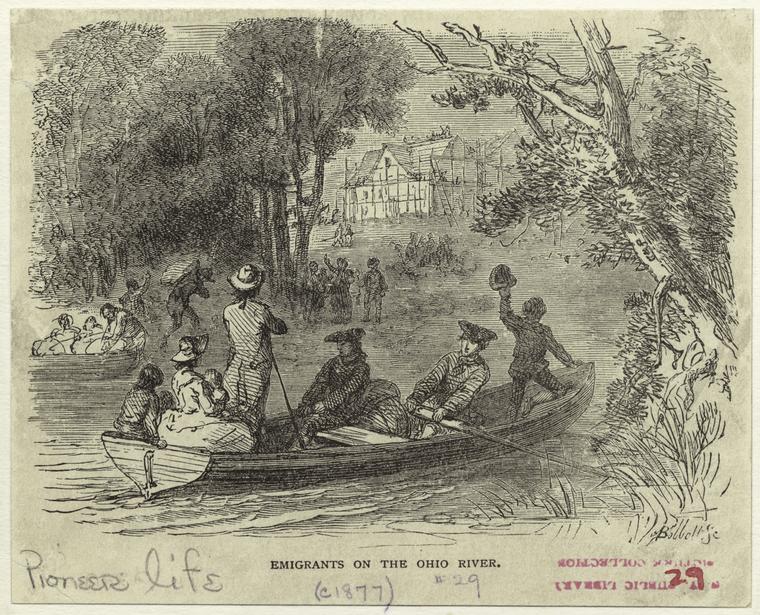

Colonial Pennsylvania and VirginiaThe Shenandoah Valley and backcountry Virginia had close ties to Pennsylvania. The two colonies even overlapped in the territory around Pittsburgh—a dispute that was not settled until 1780. The vast majority of Virginia's western settlers were Protestant Irish and German immigrants who came from Philadelphia via the Great Wagon Road, either immediately or over the course of one or two generations.

Pre-War Political and Indian Conflict

New England and Canada (1775-1776)The first truly Continental soldier were Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania frontier riflemen who were recruited to support the 1775 siege of Boston. Some, including Daniel Morgan, participated in the invasion of Canada.

The Ouster of Lord Dunmore (1775-1776)

The 8th Virginia Regiment

Virginia Continentals

The First Southern Campaign (1776)

The Mid-Atlantic Campaign (1776-1777)

The Philadelphia Campaign (1777)

The Saratoga Campaign (1777)About 400 Virginia and Pennsylvania marksmen reinforced the northern army late in the summer of 1777 and participated in the battles at Freeman's Farm and Bemis Heights leading to the surrender of British Gen. John Burgoyne.

The Western War

The Second Southern Campaign (1780-1781)

The Yorktown Campaign (1781)

The Late War (1782-1783)

The Constitution and Western Settlement

For American purposes, the best definition of "frontier" is the westward-moving zone of conflict between Indian life and encroaching white settlement. Though gunfights and broken treaties are best remembered, life on the frontier also involved now hard-to-conceive cultural role reversals. White men sometimes dressed like Natives and Indians sometimes dressed like white men. There were Christian Indians and white-skinned Indian warriors. Time, disinterest and fear of political incorrectness have erased most vestiges of Indian influence from mainstream American life, but those influences and interactions were once quite strong and sometimes had tragic consequences. Here, with all of its political incorrectness preserved, are the "reminiscences of a Western traveler" published in the Southern Literary Messenger. Though published anonymously, the author is believed to be Nathaniel Beverley Tucker, a Virginia aristocrat and literary light of the antebellum South who collaborated with Edgar Allen Poe. Tucker lived in the west for a time before returning to Virginia. From the Reminiscences of a Western Traveler

The speaker was a tall, handsome man, uncommonly stout, with an appearance of great strength, perfect health, and a quiet good humor, which disposed him to be communicative, merely by way of obliging. Though by no means garrulous, I had discovered that he was ready to tell whatever another might be desirous of hearing. He spoke with that strong accent, and deliberate tone, which characterize the Scotch Irish race, and which always, to my ear, conveys a promise that what is said will be said distinctly and clearly. Here then was the very man I wanted. I had left the peaceful scenes of the Atlantic coast, expecting, not indeed to "roam through anters vast and deserts wild," in my western tour, (for my maps and gazetteer had taught me better,) but to find some traces of the scenes, which but a few years before, had made it dangerous for a white man to set his foot where we now rode along securely. My eye had eagerly scanned every object which afforded promise of food to my young and eager imagination; but as yet I had found none. The soft beauty and exuberant fertility of the country, need only the touch of civilization to take from it every appearance of wildness, and I could hardly bring myself to believe that it had been so lately the haunt of the prowling savage. My enthusiasm was consequently much damped; but it was not extinguished, and these last words of my companion blew it into a flame. A well directed question soon drew him out. "I was born," said he, "among the mountains of Virginia. I never saw my father. He was killed at the battle of Point Pleasant, just before I came into the world. That is the reason why I said that Indian fighting had to do with me before I was born. But that was not all; many years before that, the Indians made a break on our settlement, and carried off my oldest brother, and kept him." "Did you never see him again?" "I suppose I have, but I did not know it at the time." As he said this, a gloom came over his countenance, which checked my inquisitiveness, and he rode on, perhaps a mile, in moody silence. At length his brow cleared, and he again spoke, but in a somewhat saddened tone. "It is something strange; I am not superstitious, and yet it seems to me, as if at times, when people are in great distress of mind, they are apt to say things that turn out almost like a prophecy. It was a great grief to my mother, the loss of her child, and the longer she lived the more she mourned after him. He was quite small when they took him; and they carried him away over the lakes, so far, that they never heard where he was, until he was almost grown up, a perfect wild man. My mother was a religious woman; and the thought of his being brought up among savages, where the word of God could never reach him, went to her heart. She said, it was always borne upon her mind that he was not dead, and that he would grow up among those vile wretches, to be the death of his own father, and perhaps to die at last by the hand of one of his own brothers. When they raised a party to follow the Indians, she would go with them, and all the way, she said, she looked and looked, in hopes to see where they had dashed out her poor child's brains against a tree. It was the only comfort she hoped for, and that was denied her. "As I told you, they never heard of him till he was near or quite a man; and that was just before Dunmore's war. There was no chance to do any thing towards getting him home at that time, for it was dangerous to go near the Ohio. Indeed, all they knew was, that there was a white man of about his age among the Indians, who answered to his name. It was not until after the peace that we knew certainly all about him. "Well! he was at the battle of the Point, fighting among the Shawanees; and there my father was killed. When my mother heard that he had been there, you may be sure her own words came back to her. No body knew who killed my father. But why not he as well as another? Flesh and blood could not have made her believe that it was not he. "Just after that I was born, and then again my mother took it into her head that I had come into the world to revenge my father's death. There was no great comfort in that thought, you may be sure; so as soon as the war was over, they tried all they could to get my brother back. He was told that my father was dead, and had left a good estate; and that he was the heir at law; (for you know that my father died under the old law,) but it all would not do. He was a complete Indian, and had an Indian wife and children that he would not leave. But he had kind feelings for us all, and sent us word to take the estate; for he wanted nothing but his rifle. "Well! my mother died; and I and a brother a little older than me, sold out and went to Kentucky. Where we settled was a dangerous frontier near the Ohio, and the Indians once or twice every year, would come over and strike at us. Then we would raise a party, and follow them away almost to the lakes; and after we got strong enough, we commonly kept a smart company ranging about on that side of the river. Sometimes we volunteered; sometimes we were drafted; sometimes one went; sometimes another. One year my brother went, and had a fight with the Indians. Afterwards we heard that our wild brother was in that fight, and was badly wounded. The next year I went out, and we had a fight, and my poor brother was there again, and he was killed." He ceased speaking, and again sunk into a gloomy silence, which none of us were disposed to interrupt. At length he said, in a softened voice, "Thank God! I was spared one thing. I never think of it, that it does not make the cold chills run over me. It was the night before the battle. We had been following hard upon the trail all day, and just before night we came up with them. But we did not let them see us, and lay back till they had camped for the night. We knew we could find them in the dark by their fires. Sure enough we soon saw the light, and crawled towards it. The word was to attack at day light. In the meantime every man was to keep his eye skinned, and his gun in his hand, and not to fire on any account till the word was given. But in this sort of business every man fights, more or less, on his own hook; and if a fellow only kills an Indian, they never blame him. There they were, all dead asleep, around their fire; and we standing looking at them, almost near enough to hear them snore. You may be sure we did not breathe loud. Well! while I was standing off on one flank, watching them with all my eyes, up gets one, and stands right between me and the light. Up came my rifle to my face. It was against orders, but I never had shot at an Indian, and how could I stand it? My hand was on the trigger, when the figure turned, and I saw the breasts of a woman. You may be sure I did not shoot. It was my brother's daughter, as I afterwards learned." This story required no comment. It admitted of none. The ideas it suggested was such as reason could neither condemn nor justify. We could only muse on it in silence. At length, the other stranger, who, like myself, had listened attentively, said, "I too was once within an ace of shooting a woman." I started at this, and turned to reconsider the speaker. I had already scrutinized him pretty closely, and had formed a judgment concerning him, which these words quite unsettled. The idea that he had been familiar with scenes, where every man must make his hand guard his head, had never entered my mind. He was indeed formidably armed, carrying a brace of pistols in his belt, and another in his holsters. The handle of a dirk peeped through the ruffle of his shirt, and a rifle on his shoulder completed his armament. I had been of course struck with an equipment so warlike, but attributed it to excess of caution. The mildness and elegance of his manners had fixed him in my mind, as one bred up in the scenes of peaceful and polished life, where, in youth, he had heard so much of the perils of the country he was now traversing, as to suppose it unsafe to visit it without this load of weapons. I certainly had never seen a man of more courteous and gentlemanlike demeanor; and though his countenance gave no token of one "acquainted with cold fear," I had nevertheless, emphatically marked him as a man of peace. He was the oldest man in company, but deferential to all, accommodating, obliging, and, on all occasions, modestly postponing himself, even to such a boy as I was. He seemed now to have spoken from a wish to divert the painful thoughts of our companion, and, in answer to an inquiring look from me, went on with his story. "It was nearly thirty years ago," said he, "I was travelling from Virginia through the wilderness of Kentucky, then much infested by Indians. I had one companion, an active, spirited young man, and we were both well mounted and well armed. Vigilance alone was necessary to our safety, and as we had both served a regular apprenticeship to Indian warfare, we were not deficient in that. We soon overtook a company of moving families, who had united for safety. The convenience of the axes of the men, in making fires, and of the women in cooking, determined us to join them. We camped together every night; and as we derived great advantage from the association, we tried to requite it by our activity and diligence as scouts and flankers. We commonly rode some distance ahead, so as to give them time to prepare in case of attack; depending on our own diligence and skill to guard against surprise. "Riding thus one day, a mile or two in advance, we were suddenly startled by an outcry from behind, which was not to be mistaken. We immediately drew up, and presently saw our party hurrying towards us, in great confusion and alarm, whipping up their teams, and only stopping long enough to say that they were pursued. The rear was therefore now our post, and, waiting till they had all passed, we dismounted,—hid our horses, took trees, and awaited the enemy. I did not wait long, until I saw the head and shoulders of a figure above the undergrowth, rushing at full speed towards me. My rifle was at my cheek, and a steady aim at the advancing figure made me sure of my mark, when an opening in the brushwood showed me the dress of a female. She was the wife of one of the wretches who had just passed us, completely spent and sinking with fatigue. Had there been Indians she must have perished. As it was, her appearance showed the alarm to be false; so I took her up behind me, and we went quietly on, in pursuit of her dastard husband, to whose protection I restored her." In speaking these last words, the face of the speaker underwent, for a moment, a change, which told more than his story. The tone of scornful irony too, which accompanied the word protection, gave a new face to his character. As I marked the slight flush of his pale and somewhat withered cheek, the flash of his light blue eye, the curl of his lip, and a peculiar clashing of his eye-teeth as he spoke; I thought I had rarely seen a man, with whom it might not be as safe to trifle. The day was now far spent; and as the sun descended, we had the satisfaction to observe that he sank behind a grove, that marked the course of a small branch of the Wabash, on the bank of which stood the house where we expected to find food and rest. None but a western traveller can understand the entire satisfaction with which the daintiest child of luxury learns to look forward to the rude bed and homely fare, which await him, at the end of a hard day's ride, in the infant settlements. There is commonly a cabin of rough unhewn logs, containing one large room, where all the culinary operations of the family are performed, at the huge chimney around which the guests are ranged. The fastidious, who never wait to be hungry, may turn up their noses at the thought of being, for an hour before hand, regaled with the steam of their future meal. But to the weary and sharp set, there is something highly refreshing to the spirits and stimulating to the appetite. The dutch oven, well filled with biscuit, is no sooner discharged of them, than their place is occupied by sundry slices of bacon, which are immediately followed by eggs, broken into the hissing lard. In the mean time, a pot of strong coffee is boiling on a corner of the hearth; the table is covered with a coarse clean cloth; the butter and cream and honey are on it; and supper is ready. "Then horn for horn they stretch and strive." It makes me hungry now to think of it; and I am tempted to take back my word and eat something, having just told my wife I wanted no supper. But it will not do. I have not rode fifty miles to-day, and my table is so trim and my room so snug that I have no appetite. But it is only in the first stage of a settlement, that these things are found. By and by, mine host, having opened a larger farm, builds him a house, of frame-work or brick, the masonry and carpentry of which show the rude handy-work of himself and his sons. He now employs several hands, and the leavings of their dinner will do for the supper of any chance travellers in the evening. A round deep earthen dish, in which a bit of fat pork or lean salt beef, crowns a small mound of cold greens or turnips, with loaf bread baked a month ago, and a tin can of skimmed milk now form the travellers supper. It is vain to expostulate. Our host has no fear of competition. He has now located the whole point of wood land crossed by the road, and no one can come nearer to him, on either hand, than ten miles. Besides, he is now the "squire" of the neighborhood, with "eyes severe," and "fair round belly with fat bacon lined;" and why should not the daily food of a man of his consequence be good enough for a hungry traveller? It was to a house of this latter description that we now came. No one came out to receive us. Why should they? We took off our own baggage, and found our way into the house as we might. On entering, I was struck with the appearance of the party, as their figures glimmered through the mingled lights of a dull window and a dim fire. Each individual, though seated, (and no man moved or bad us welcome) wore his hat, of shadowy dimensions; a sort of family resemblance, both in cut and color, ran through the dresses of all; and a like resemblance in complexion and cast of countenance marked all but one. This one, as we afterwards found, was the master of the mansion, a man of massive frame, and fat withal, but whose full cheeks, instead of the ruddy glow of health, were overcast with an ashy, dusky, money-loving hue. In the appearance of all the rest there was something ascetic and mortified. But landlord and guest wore all one common expression of ostentatious humility and ill-disguised self-complacency, which so often characterizes those new sects, that think they have just made some important discoveries in religion. Mine host was, as it proved, the Gaius of such a church, and his guests were preachers of the same denomination. I have forgotten the name; but they were not Quakers. I have been since reminded of them, on reading the description of the company Julian Peveril found at Bridgnorth's. When we entered, our landlord was talking in a dull, plodding strain, and in a sort of solemn protecting tone, to his respectfully attentive guests. Our appearance made no interruption in his discourse; and he went on, addressing himself mainly to a raw looking youth, whose wrists and ankles seemed to have grown out of his sleeves and pantaloons since they were made. Where the light, which this young man was now thought worthy to diffuse, had broken in upon his own mind, I did not learn, but I presently discovered that he came from "a little east of sunrise," and had a curiosity as lively as my own, concerning the legends of the country. "I guess brother P——," said he, "you have been so long in these parts, that it must have been right scary times when you first came here." "Well! I cannot say," replied the other, "that there has been much danger in this country, since I came here. But if there was, it was nothing new to me. I was used to all that in Old Kentuck, thirty years ago." "I should like," said the youth, "to hear something of your early adventures. I marvel that we should find any satisfaction in turning from the contemplation of God's peace, to listen to tales of blood and slaughter. But so it is. The old Adam will have a hankering after the things of this world." "Well!" replied our host, "I have nothing very particular to tell. The scalping of three Indians, is all I have to brag of. And as to danger; except having the bark knocked off of my tree into my eyes, by a bullet, I do not know that I was ever in any mighty danger, but once." "And when was that?" "Well! It was when we were moving out along the wilderness road. You see it was mighty ticklish times; so a dozen families of us started together, and we had regular guards, and scouts, and flankers, just like an army. The second day after we left Cumberland river, a couple of young fellows joined us, one by the name of Jones, and I do not remember the other's name. I suppose they had been living somewhere in Old Virginia, where they had plenty of slaves to wait on them; and it went hard with them to make their own fires, and cook their own victuals; so they were glad enough to fall in with us, and have us and our women to work and cook for them. But a man was a cash article there; and they both had fine horses and good guns; and, to hear them talk, (especially that fellow Jones,) you would have thought, two or three Indians before breakfast, would not have been a mouthful to them. We did not think much of them, but we told them, if they would take their turn in scouting and guarding, they were welcome to join us." At this moment, our landlady, who was busy in a sort of shed, which adjoined the room we sat in, and served as a kitchen, entered, and stopping for a moment, heard what was passing. She was a good-looking woman, of about forty-five, with a meek subdued and broken hearted cast of countenance. I saw her look at her husband, and as she listened, her face assumed an expression of timid expostulation, mixed with that sort of wonderment, with which we regard a thing utterly unaccountable, but which use has rendered familiar. Her lord and master caught the look, and bending his shaggy brow, said, "I guess the men will want their supper, by the time they get it." She understood the hint, and stole away rebuked; uttering unconsciously, in a loud sigh, the long hoarded breath which she had held all the time she listened. Her manner was not intended to attract notice; but there was something in it, which disposed me to receive her husband's tale with some grains of allowance. He went on thus: "The day we expected to get to the crab-orchard, it was their turn to bring up the rear. By good rights, they ought to have been a quarter of a mile or so behind us; and I suppose they were; when, all of a sudden, we heard the crack of a rifle, and here they come, right through us, and away they went. I looked round for my woman and I could not see her. The poor creature was a little behind, and thought there was no danger, because we all depended on them two fire eaters in the rear, to take care of stragglers. But when they ran off, you see, there was nobody between her and the Indians; and the first thing I saw, was her, running for dear life, and they after her. I set my triggers, and fixed myself to stop one of them; and just then, her foot caught in a grape vine, and down she came. I let drive at the foremost, and dropped him; but the other one ran right on. My gun was empty; and I had no chance but to put in, and try the butt of it. But I was not quite fast enough. He was upon her, and had his hand in her hair; and it was a mercy of God, he did not tomahawk her at once. He had plenty of time for that;—but he was too keen after the scalp; and, just as he was getting hold of his knife, I fetched him a clip that settled him. Just then, I heard a crack or two, and a ball whistled mighty near me; but, by this time, some of our party had rallied, and took trees; and that brought the Indians to a stand. So I put my wife behind a tree, and got one more crack at them; and then they broke and run. That was the only time I ever thought myself in any real danger, and that was all along of that Jones and the other fellow. But they made tracks for the settlement." "Have you never seen Jones since?" said the mild voice of the courteous gentleman I have mentioned. "No; I never have; and it's well for him; though, bless the Lord! I hope I could find in my heart now to forgive him. But if I had ever come across him, before I met with you, brother B——;" (addressing a grave senior of the party who received the compliment with impenetrable gravity;) "I guess it would not have been so well for him." "Do you think you would know him again, if you were to see him?" said my companion. "It's a long time ago," said he, "but I think I should. He was a mighty fierce little fellow, and had a monstrous blustering way of talking." "Was he any thing like me?" said the stranger, in a low but hissing tone. The man started, and so did we all, and gazed on the querist. In my life, I never saw such a change in any human face. The pale cheek was flushed, the calm eye glowed with intolerable fierceness, and every feature worked with loathing. But he commanded his voice, though the curl of his lip disclosed the full length of one eye tooth, and he again said, "look at me. Am not I the man?" "I do not know that you are," replied the other doggedly, and trying in vain to lift his eye to that which glared upon him. "I do not know that you are?" muttered he. "Where is he? where is he," screamed a female voice; "let me see him. I'll know him, bless his heart! I'll know him any where in the world." Saying this, our landlady rushed into the circle, and stood among us, while we all rose to our feet. She looked eagerly around. Her eye rested a moment on the stranger's face; and in the next instant her arms were about his neck, and her head on his bosom, where she shed a torrent of tears. I need not add, that the subject of the Landlord's tale, was the very incident which my companion had related on the road. He soon made his escape, cowed and chop-fallen; and the poor woman bustled about, to give us the best the house afforded, occasionally wiping her eyes, or stopping for a moment to gaze mutely and sadly on the generous stranger, who had protected her when deserted by him who lay in her bosom. The grave brethren looked, as became them, quite scandalized, at this strange scene. It was therefore promptly explained to them; but the explanation dissipated nothing of the gloom of their countenances. Their manner to the poor woman was still cold and displeased, and they seemed to forget her husband's fault, in their horror at having seen her throw herself into the arms of a stranger. For my part, I thought the case of the good Samaritan in point, and could not help believing, that he who had decided that, would pronounce that her grateful affection had been bestowed where it was due. Originally Published in the Southern Literary Messenger, 1:7 (1835), pp.336-340. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

Introductions to the Revolutionary War

Late Colonial Virginia

Virginia in the Revolution

The War in 1776

The War in 1777

The War in 1778

The Later War and the Western Theater

Officer Biographies

After the War

Battlefield Guides

Reference

More from The 8th Virginia RegimentThe homes of several 8th Virginia veterans survive in Virginia, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and Indiana. Some were the houses they grew up in and others were built in their final years of life. Some survive only in photographs. If you know of others, please let us know so we an include them here.

Though still insufficiently covered in classrooms, the Battle of Kings Mountain is recognized as the key event in the demonstration of popular southern refusal to submit to Loyalist rule. Even less well-remembered is the smaller Battle of Musgrove’s Mill, without which there may have been no Kings Mountain. It was a little encounter in which just 200 Patriot militiamen faced off against 264 Loyalist regulars and militia. Though small, it sent a strong signal that backcountry Americans simply would not be ruled any longer by a foreign king. Giving such small battles their due is the purpose of Westholme Publishing’s “Small Battles” series. The Battle of Musgrove’s Mill, 1780 comes from the pen of John Buchanan, the undisputed dean of southern Revolutionary War history. Now in his 90s, Buchanan writes as well as ever. In fewer than a hundred pages, he puts the story in context; explains the British, Tory, Indian, and Patriot perspectives; tells us about the key commanders on both sides; narrates the battle; and tells us why it matters. That is a lot to put into eighty-eight pages of text, but he has done it masterfully. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment |

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed