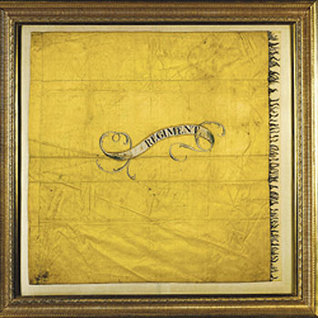

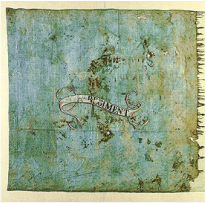

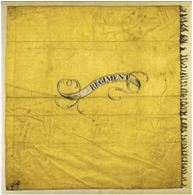

See “The Grand Division Standard” (June 20, 2022) for a corrected and updated version of this post.Here are images of all three known Virginia regimental standards, shown together apparently for the first time. All three flags are in anonymous private collections but have been exhibited publicly. The flag in the middle belonged to the 8th Virginia. One of the other flags reportedly belonged to the 3rd Virginia. The faded rectangle in the center of the 8th Virginia flag is a consequence of light damage resulting from the way in which it was displayed for many years--it was originally one consistent (salmon) color. The flags follow an apparently standard design, but in varying colors. The color was the most important distinguishing characteristic of the flags, which were used to help troops stay organized in the smoke and confusion of battle.

The scrolls on the blue and yellow flags contain only the word "regiment." This suggests that they were made at the same time, with the intention that regiment numbers would be added when the colors had been assigned to the respective units. (The word "regiment" is not centered in the scrolls; space was retained to the left of the word on both flags.) The writing in the 8th Virginia's scroll is illegible because of light damage. The writing was retouched on the reverse side of the flag to say "VIII Virg Regt." An 1847 account in the Richmond Whig says the scroll contained the words "VIII Virga Regt." This sets it apart from the other two flags. This can be explained by the history of Virginia's Continental regiments. The 1st and 2nd regiments were authorized by the Virginia convention in 1775 for one-year enlistments. Seven more regiments were authorized in December of 1775 to be formed in 1776 for two-year enlistments, with the expectation that the 1st and 2nd would also continue with new or reenlisted men. Virginia expected all of these regiments to be taken into the Continental Army. Congress, however, initially only authorized seven Virginia Continental regiments. Despite being the first regiment to leave the Commonwealth in Continental service, the 8th drew the short straw and was not recognized immediately as anything other than a provincial (after July 4, "state") regiment. (The same was true of the small 9th regiment, which was created only for Eastern Shore defense.) At the urging of General Charles Lee, Congress later increased the number of authorized Virginia Continental regiments. One consequence of this complicated history may be that the 8th Virginia's regimental standard was not made at the same time as the other banners.

1 Comment

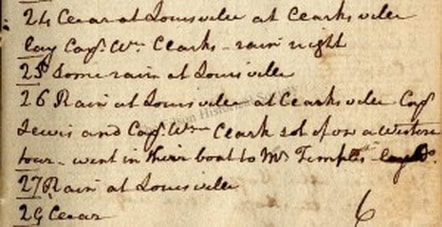

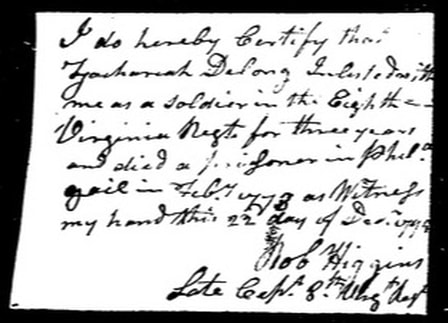

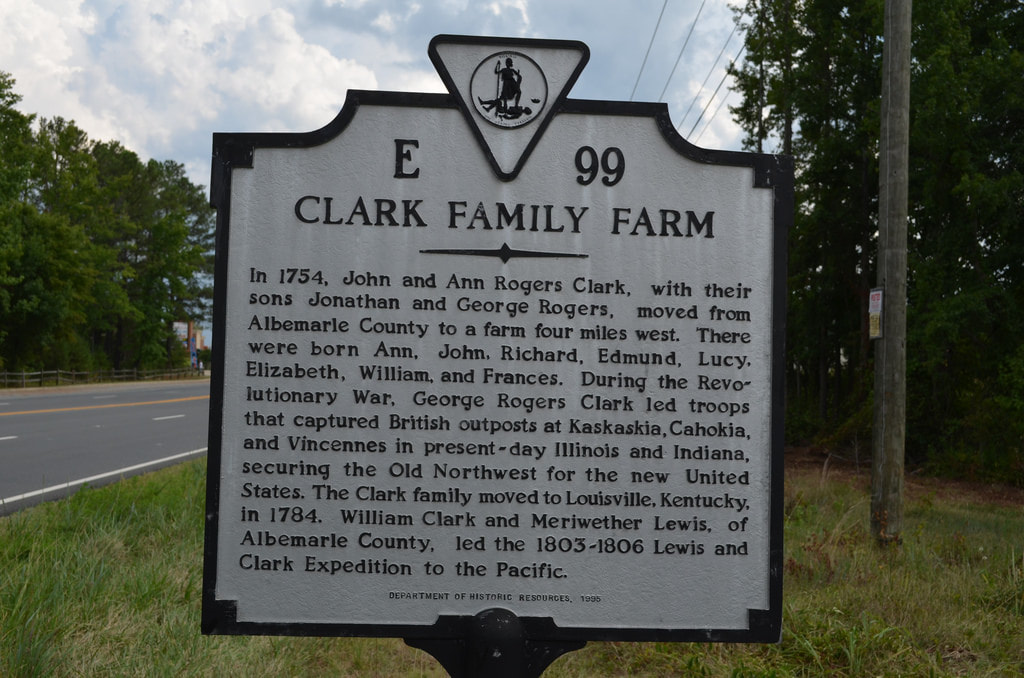

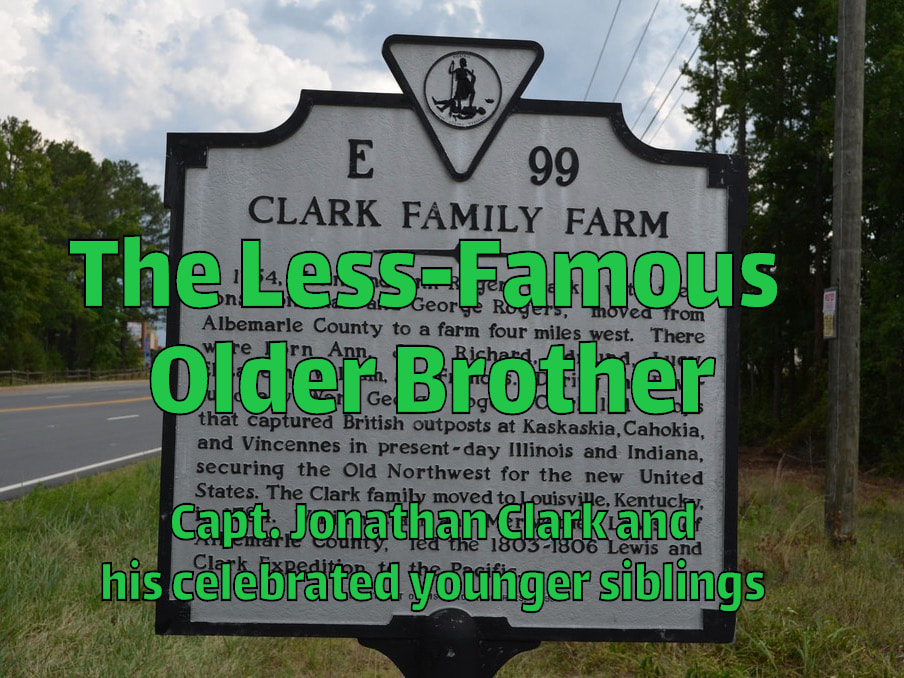

Jonathan Clark faithfully kept a diary, but it only records the weather, his location, and a few more words about each day. Jonathan Clark faithfully kept a diary, but it only records the weather, his location, and a few more words about each day. Jonathan Clark was one of the 8th Virginia’s ten company captains. He was the older brother of the explorer William Clark, famous for the Lewis and Clark expedition. He was also the older brother of George Rogers Clark, the victor of the now-obscure Battle of Vincennes, which won the old “northwest territory” from the British in the Revolution. Did you ever wonder how all the territory east of the Mississippi became American territory after the war, not just the 13 colonies? The answer is George Rogers Clark. Jonathan Clark was an important figure in his own right, and left the only comprehensive diary of the 8th Virginia’s experiences in the war. It is frustratingly concise, but also crucially important in piecing the regiment's history together. Jim Holmberg, a Kentucky historian and archivist, wrote a blog post about the eldest Clark brother four years ago on the bicentennial of his death. You can read it here. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment On February 7, 1776, John Stump was one of the earliest recruits to join the 8th Virginia. He was recruited by Captain Abel Westfall or one of his lieutenants to join their new company of Virginia provincial soldiers. The company was one of ten that would make up the 8th Virginia Regiment. John was probably the son of Michael Stump, a German who had changed his name from Hans Stumpff. John marched with the regiment to South Carolina in the summer of 1776 and was present for the Battle of Sullivan's Island. The joy of that victory was followed by a summer and fall of intense suffering. The soldiers of the 8th fell victims to malaria--a mosquito-born illness these men from the mountains were ill-prepared for. After a planned invasion of British Florida was called off, they sat sick in camp at Sunbury, Georgia--a few of them dying nearly every day. When winter came and the malarial season ended, they hobbled back to Virginia. In the spring, those who were healthy enough marched off to join Washington's "Grand Camp" in New Jersey. They walked north, crossing the Potomac at Harper's Ferry through Maryland into Pennsylvania before heading east through York, Lancaster, and Philadelphia. John Stump, however, couldn't make it much past Harper's Ferry. Muster rolls for the rest of the year report that he was "left sick in Maryland." After this, there is no further (discovered) record of him being alive. It could have been malaria, smallpox, or another disease--but John Stump probably died somewhere near Frederick, Maryland. This was the fate of many 8th Virginia soldiers. Disease was the primary killer of the war, and no regiment was hit harder by it than the 8th Virginia. The frontier cabin built by Michael Stump will be open for tours late this month. Records have not been found to prove it, but this is probably the cabin John Stump grew up in. Presumably, it was there that he shook his father's hand and kissed his mother's cheek before marching of to war, never to return. Current owners John and Beverly Buhl will open their doors during Hardy County Heritage Weekend, September 26 and 27. View their website for more information. See “Grand Division Flag” (June 20, 2022) for an updated version of this post. The 8th Virginia standard unveiled in 2012 by Rob Andrews and Erik Dorman. The 8th Virginia standard unveiled in 2012 by Rob Andrews and Erik Dorman. “The first time I heard of the 8th Virginia Standard was during an internet search on the 8th,” writes Rob Andrews, an SAR member and Revolutionary War reenactor with the 1st Virginia Regiment. What he found was an 1847 reference in the Richmond Whig. The newspaper quoted Peter Muhlenberg’s great nephew saying, “The regimental color of this corps (8th Virginia Regiment of the Line) is still in the [my] possession. It is made of plain salmon-colored silk, with a broad fringe of the same, having a simple white scroll in the centre, upon which are inscribed the words, ‘VIII Virga. Reg’t.’ The spear-head is brass, considerably ornamented. The banner bears the traces of warm service, and is probably the only revolutionary flag in existence.” After this, there was no discoverable mention of the flag anywhere. “I emailed the folks at Valley Forge and the Trappe Foundation in Trappe PA, where the Muhlenberg family lived. Emails bounced around and finally one person said he thought he knew who had it. I didn't hear anything for awhile and then one day an email from Bernard Goetz popped into my box with two pictures of the flag. It was in a frame and had a card at the bottom stating its provenance. I was appalled at the pictures and immediately advised Mr Goetz to remove the flag from the frame.” The flag had not been professionally conserved, had faded where it faced the glass, and was displayed with a card that claimed a service history that followed General Muhlenberg’s career—not that of the 8th Virginia (which he led for a year). “That was all I heard of it for several years,” says Rob. Sometime later, “Mr. Goetz passed away and [in 2012] his descendants placed all his historical artifacts up for auction at Freeman’s Auction in Philadelphia. Prior to the auction, Freeman’s brought it to Shenandoah County to be displayed. I was lucky that I found out about it just a couple of days prior to the event. I contacted my friend Erik [Dorman] who also was interested in writing about the 8th and we decided to show up in our uniforms. We caused quite a stir when we walked around the corner of the Courthouse into the square. We were immediately enlisted to "guard" the flag and unveil it during the event.” Rob also shares one important explanation about the flag’s appearance. “As someone in the past painted the flag so that 8th Virginia was visible” the opposite side of the flag is displayed “to show its original condition. And its years in the frame have led to its faded rectangle appearance.” As mentioned a few posts ago, the flag was purchased anonymously for $422,500 and is once again owned by an anonymous collector. Thanks to Rob Andrews for the information in this post.  Two posts ago, I featured the house of Captain Robert Higgins in Moorefield, West Virginia. Here is a note authored by Higgins in support of a post-war bounty land warrant issued to the heirs of one of his soldiers, Zachariah DeLong. I don't know much about DeLong, but the story we have is a sad one. In the fall of 1776, the enlistments of an entire company of the 8th expired. (This was John Stephenson's company, which was formed in 1775 when terms were just a year.) Short a company, Colonel Muhlenberg proposed his brother-in-law, Francis Swain (the regiment's adjutant), be made a captain. Washington rejected Muhlenberg's suggestion and promoted Lt. Robert Higgins instead. Higgins came from Capt. Abel Westfall's Hampshire County-raised company and may have been the senior surviving lieutenant in the regiment. That would explain his promotion. Higgins spent the next six months diligently attempting to recruit a new company from scratch. The euphoria of 1776, however, had been replaced by the cold reality that nearly half of the original regiment had already died, deserted, or become very sick from malaria. Higgins was never able to recruit more than about 15 men. Zachariah DeLong was one of the brave souls who signed up. Higgins brought his tiny company to the main army late in September of 1777 and quickly went into combat at Germantown on October 4. Higgins and many others were captured when they followed Major William Darke into the thick morning fog just before friendly fire put the rest of the army into a retreat. Unlike Higgins, who was a veteran of the 1776 campaign, DeLong was in Washington's Army for just a few days before he was captured. As an officer, Higgins was treated better by the British than enlisted men like DeLong. DeLong, like thousands of others, was held in conditions so terrible he could not survive them. Higgins signed at least three notes of this kind, attesting that soldiers like DeLong had indeed served under him before dying of rampant disease in a filthy British jail only four months after their capture. Peter Muhlenberg, by the way, became a brigadier general at about the same time Higgins became a captain. He appointed Francis Swain his brigade major. Swain was terrible at the job and eventually washed out of the army. Thanks to Tom Higgins of Shelbyville, Kentucky, for this document. (Updated 3/29/20) Read More: "Captain Higgins' House (8/30/15)"  This attack on the Chew House slowed the Continental advance during the Battle of Germantown. This and other causes of confusion led to a friendly fire incident. Zachariah DeLong and other advancing 8th Virginia men were captured along with the entire 9th Virginia Regiment when the rest of the army retreated. (Image: unknown artist after a painting by Alonzo Chappel) More from The 8th Virginia Regiment Most regimental standards have not survived. The flag of the 8th, though in private hands, is a truly rare gem. It is not, however, the only Virginia regimental flag to survive. The 3rd Virginia's flags also survive, because they were captured and taken to England as trophies. A comparison raises some interesting questions. Two other flags purchased in 2006 by an anonymous bidder but displayed at Williamsburg in 2007 look almost identical to the 8th Virginia's flag, but in different colors. This suggests that they belonged to different regiments, even though the flags displayed in Williamsburg are described as both having belonged to the 3rd Virginia. The color, rather than the image on the flag, was the most important thing on a smoky battlefield battlefield. These flags were used to help soldiers of a regiment stay together. Men of the 8th were to stay by the salmon-colored flag. Men of the 3rd, by this one (or a blue one). The two that were displayed in Williamsburg only say "regiment," without a number. This suggests that they were manufactured generically in various colors and that the regimental numbers were intended to be added later, but weren't in all cases. Images of the other flags displayed at Williamsburg can be seen at this link. If anyone knows more about this, please share! |

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed