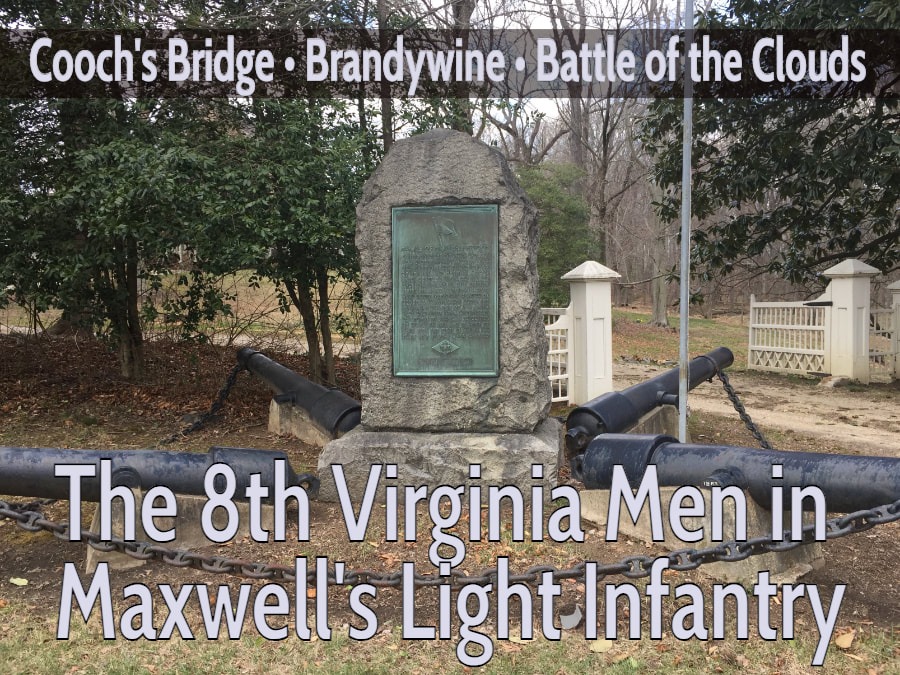

In 1777, the main body of the regiment served in Maj. Gen. Adam Stephen's division at Brandywine and Germantown. A small group of riflemen from the 8th were detached to Daniel Morgan’s Rifle Battalion under the command of Captain James Knox and participated in the Saratoga campaign. A few dozen were detached for a month to William Maxwell's Light Infantry in August and September of 1777 under the command of Captain (later and retroactively Major) William Darke, at Cooch's Bridge and Brandywine. Stephen was replaced by the Marquis de Lafayette late in the year. In 1778, with its ranks severely depleted by disease, casualties, and expired enlistments, the 8th was folded into the 4th Virginia after the Battle of Monmouth. 1776 Southern Campaign (Sullivan’s Island, Savannah, Sunbury): Gen. George Washington, Commander in Chief (not present) Maj. Gen. Charles Lee, Commander of the Southern District Brig. Gen. Andrew Lewis (Tidewater service) Brig. Gen. Robert Howe (Cape Fear, Charleston, Savannah, Sunbury) Captain Croghan Detachment attached to 1st Virginia (White Plains, Trenton, Assunpink Creek, Princeton): Maj. Gen. Joseph Spencer (White Plains) Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene (Trenton and Princeton) Col. George Weedon (temporary brigade at Fort Washington) Brig. Gen. William Alexander, Earl of Stirling (White Plains through Trenton) Brig. Gen. Hugh Mercer (Princeton) 1777 Philadelphia Campaign (Brandywine, Germantown, Valley Forge) Gen. George Washington, Commander in Chief Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln (New Jersey rendezvous) Maj. Gen. Adam Stephen (Brandywine, Germantown) Maj. Gen. Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette (Valley Forge) Brig. Gen. Charles Scott Captain Knox Detachment under Colonel Daniel Morgan (Saratoga) Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln Captain Darke Detachment in Maxwell's Light Infantry (Cooch's Bridge, Brandywine) Brig. Gen. William Maxwell 1778 Campaign (Valley Forge, Monmouth): Gen. George Washington, Commander in Chief Maj. Gen. Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette Maj. Gen. Charles Lee (at Monmouth) Brig. Gen. Charles Scott Col. William Grayson (temporary brigade commander at Monmouth) More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

5 Comments

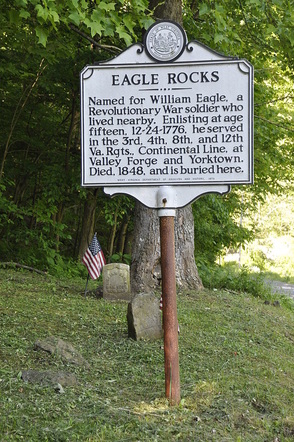

Watching news of the coordinated terrorist attacks in Paris, I'm thinking about the longstanding alliance America has with France. France was our first important ally--we may not have won the Revolution with out her. The Statue of Liberty, a gift from France, is a great symbol of our friendship. In 1777, the 8th Virginia fought at Brandywine alongside a 19 year-old French volunteer named Lafayette. After the Battle of Germantown, Lafayette was given his own Division, and the 8th was part of it. In 1921 Frank Schoonover depicted Lafayette encouraging the men in front of the regiment's banner in this painting. Many years later, America honored the alliance by sending soldiers across the Atlantic to save France. On July 4, 1917 American Colonel Charles Stanton went to Lafayette's tomb and said, "America has joined forces with the Allied Powers, and what we have of blood and treasure are yours. Therefore it is that with loving pride we drape the colors in tribute of respect to this citizen of your great republic. And here and now, in the presence of the illustrious dead, we pledge our hearts and our honor in carrying this war to a successful issue. Lafayette, we are here." The words "Lafayette, we are here!" ("Lafayette, Nous Voila!") were once famous. Ninety-eight years ago, they gave hope to France--even to those behind enemy lines. They gave meaning to the service of that war's late-arriving American troops and to the sacrifice of those who stormed the beaches of Normandy 27 years later. The World War I generation is gone, and the currency of the phrase has largely gone with them. Today is a good day to revive it.  In my October 29 post about William Eagle, I wrote that he "enlisted in the 8th Virginia on Christmas Eve, 1776" and that he "was one of the first to sign up when the regiment came limping back to Virginia from its encounters with redcoats and ... malaria in South Carolina and Georgia." I gave him credit for being "one of the few who enlisted during the Revolution’s darkest hour." Well, it's not true. His pension says it's true and the West Virginia historic marker that stands next to his grave says it's true. But they are both wrong. First, His name appears nowhere in the muster or pay rolls for 1777, and the "commencement of pay" date for on his first pay roll entry is February 1, 1778. Second, His pension affidavit claims that he "enlisted for the term of three years, on or about the 24th day of December in the year 1776, in the state of Virginia in the Company commanded by Captain Stead or Sted or Steed, in the Regiment commanded by Colonel Nevil or Neville." Colonel John Neville (no known relation to me) commanded the regiment after it was folded into the 4th Virginia in the fall of 1778. Had Eagle enlisted in the regiment in December of 1776 and joined it in January of 1777 he would certainly have mentioned Colonel Abraham Bowman, who became a "supernumerary" officer when the regiment was folded into others in the summer of 1778 and released from service in the fall. Eagle served under Bowman only for a little while and, consequently, did not mention him. Eagle got the names right (Neville and Steed), but the year wrong. Third, the term of his enlistment is consistently recorded as for 3 years or the length of the war (which ever was shorter). Soldiers who enlisted in 1777 or later enlisted under these terms. Virginia soldiers who enlisted in 1776 signed up for two years. (Someone might argue that a date so late in the year might have been treated differently, but I'm not aware of any examples of this.) The date of his enlistment is not recorded anywhere in the surviving official records. From the evidence, however, it seems certain that he in fact enlisted "on or about the 24th day of December" in the year of 1777 (not 1776), and joined the regiment at Valley Forge about a month later. Eagle is not the only veteran who got the dates of his service wrong when applying decades later for a pension. It is an understandable error. The State of West Virginia might, however, want to invest in an updated marker.  Mosquitos were an unrecognized but deadly enemy in the Revolutionary War, and no troops suffered more from them than the 8th Virginia. The current plague of mosquitos in South Carolina is a reminder of what Colonel Peter Muhlenberg and his men had do deal with in the summer and fall of 1776. After record October rainfalls, South Carolina is presently experiencing record numbers of mosquitos, and citizens are calling for state or even federal action to combat the bugs. Tony Melton of Florence, S.C., told a reporter this week that mosquitos were “eating me alive” the last time he tried to ride his tractor through his sweet potato field. “People are stayng inside; that’s the bottom line.” Mosquitos are nothing new to South Carolina. In 1774 a resident called them “devils in miniature.” In May of 1776, The 8th Virginia Regiment rushed south from Virginia to help defend Charleston, South Carolina. On their arrival, Captain Jonathan Clark spent much of the first week staying at the home of Christopher Gadsden. He initially camped in Gadsden’s garden, but recorded that upon the “arr[ival] of [the] Moschetto” he got up and moved “in the House.” Enlisted men didn't have the option. The Battle of Sullivan’s Island on June 28 was a major early victory for the Americans, and the successful defense by South Carolina provincial troops of the Island’s half-finished fort was regarded as a virtual miracle. About three companies of the 8th Virginia (Continental troops) were posted at the opposite end of the island blocking a cross-channel infantry attack. Major General Lee praised his Continentals after the battle. “I know not which Corps I have the greatest reason to be pleased with Muhlenberg’s Virginians, or the North Carolina troops—they are both equally alert, zealous, and spirited.” Though they fended off the British, many of them lost their battle with the mosquitos. Unlike the mosquitos bothering Tony Melton, the mosquitos of 1776 carried malaria. By August, 150 8th Virginia men were sick. By fall, a few were dying every day. Muhlenberg got it and would never fully recover. Major Peter Helphinstine got it and was so sick he was forced to resign his commission and died a slow death at home in Virginia. As measured by death and illness, malaria was the 8th Virginia's number one enemy in the war--and nobody knew what caused it. Most people thought it was bad air ("mal aria") hovering over swamps and other areas. In fact, it was the mosquitos that breaded in such places.Today, malaria has been eradicated in South Carolina, Georgia and other warm, wet areas of the United States. It continues to kill millions every year in Africa and other developing parts of the world. |

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed