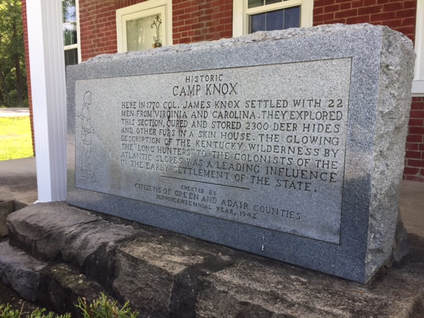

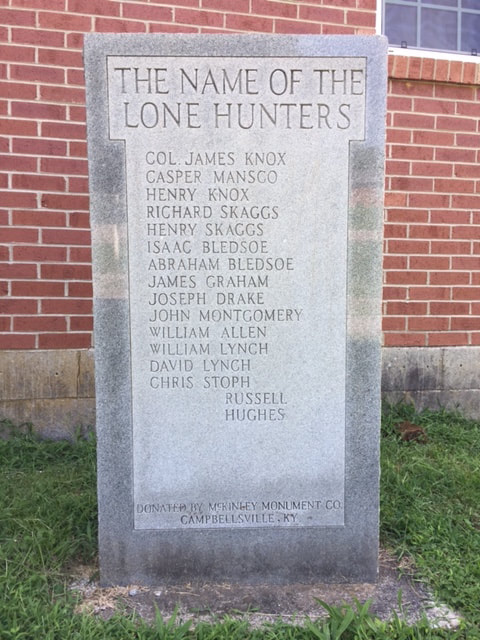

8th Virginia Captain James Knox was one of the original "long hunters," the first white men to go deep into "Kentucky country" through Cumberland Gap. 8th Virginia Captain James Knox was one of the original "long hunters," the first white men to go deep into "Kentucky country" through Cumberland Gap. The adventures of 8th Virginia Captain James Knox have been unfairly overshadowed by those of Daniel Boone. This may be true generally, but it is definitely—and literally—true at the site of a memorial marker in Greene County, Kentucky. The 8th Virginia’s recruitment area was vast—covering almost the entire Virginia frontier, which at that time stretched from Pittsburgh to the Cumberland Gap—a distance of 450 miles. Those two places were, at that time, the only practical access points to the “Kentucky Country”—all of which was, at the start of the war, part of Fincastle County, Virginia. To get there, you could float down the Ohio River from Pittsburgh, or you could travel overland through the Cumberland Gap. Few had taken the latter route, however, when James Knox led a hunting party that way in 1770. Knox was one of the original “Long Hunters,” who entered Kentucky on months-long or even years-long hunting trips, intending to return with large quantities of pelts. Daniel Boone is by far the most famous of the long hunters, but that is partly because there is only room for one of these little-remembered adventurers in public memory. In 1770, James Knox and his team established a hunting camp and pelt repository (a “skin house”) by the north bank of a creek now known as Skinhouse Branch. Years later, a church was built on the same site. Today, the 187-year old nondenominational church sits at the intersection of Skinhouse Branch and Long Hunters Camp roads—neither of which carries enough traffic to warrant painted markings. It is surrounded by farms growing corn, tobacco, and soybeans. Two stone markers were put there long ago by local citizens to memorialize James Knox and the hunting expedition of 1770. In front of them, and closer to the road, is an official Kentucky state historic marker noting that Daniel Boone was also there—a year later. Early in 1776, Knox recruited one of the 8th Virginia’s ten companies. His men were decimated by malaria during the South Carolina expedition of that summer and fall. By the spring of 1777, only a handful were left. Knox became a captain in Morgan’s Rifles and commanded a company at the victory at Saratoga. He took a few of his 8th Virginia men with him, and his 8th Virginia Regiment company ceased to exist. He was a prominent citizen of Kentucky in his later years, but has always been overshadowed by Daniel Boone. Read More: "Searching for Captain Knox" (3/29/18)

3 Comments

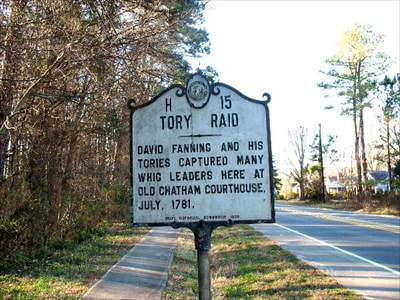

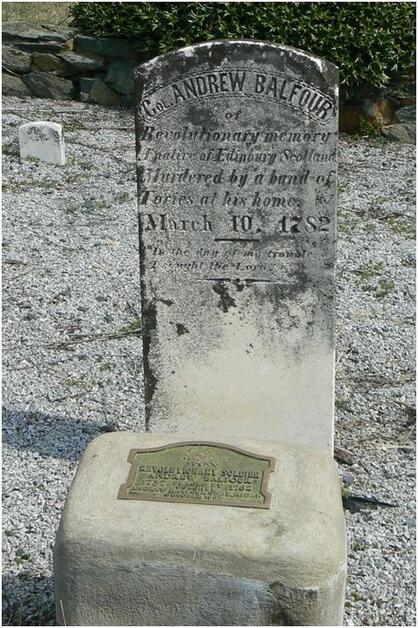

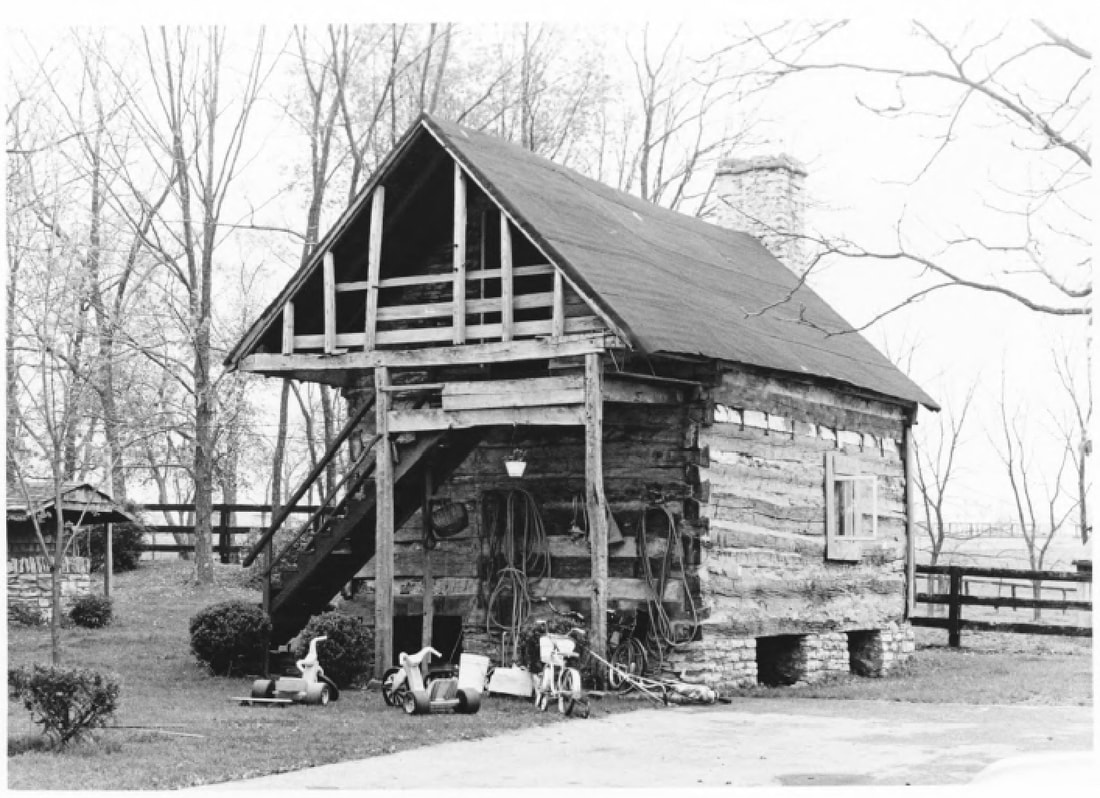

Colonel Abraham Bowman's Kentucky cabin in 2017, as restored circa 2002. Colonel Abraham Bowman's Kentucky cabin in 2017, as restored circa 2002. 8th Virginia Colonel Abraham Bowman’s frontier cabin looks better than has in 200 years. Frontier log cabins, usually built of American Chestnut on stone foundations, were very durable structures. A surprising number of them survive today, including the cabin 8th Virginia Colonel Abraham Bowman built about 1779 or 1780 when he moved to Kentucky. Nevertheless, after two centuries, the Bowman cabin showed signs of deterioration (and alteration) when images of it were submitted to the National Park Service in 1979. Bowman and his brothers are remembered as accomplished equestrians, reportedly known back in the Shenandoah Valley as the “Four Centaurs of Cedar Creek.” Appropriately, most of his land in Kentucky is now part of one of the most important equestrian facilities in the world. His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the Emir of Dubai and Prime Minister of the United Arab Emirates, is a horse enthusiast and owner of a global thoroughbred stallion operation which stands stallions in six countries. Soon after acquiring the property in 2000, Sheikh Mohammed had the Bowman cabin repaired and restored, along with other properties built long ago for Bowman’s children. The unique cabin, which features a basement and an exterior staircase to a second floor, has never looked better. The most notable change from the restoration is the reorientation of the exterior stairs, presumably to their original position and providing more headroom over the basement stairs.  David Fanning was a notoriously violent Loyalist officer. (Waymarking.com) David Fanning was a notoriously violent Loyalist officer. (Waymarking.com) Of all the Tories engaged in the brutal southern theater of the Revolution, none has a worse reputation than Colonel David Fanning. His savagery was matched only by his loyalty to the Crown. Fanning’s career and writings offer an unfamiliar perspective on the war and its aftermath. Fanning used fear and violence to keep his part of North Carolina loyal, or at least neutral. “On one occasion, Fanning and his troop called at a smithshop to get their horse shoes repaired, where he met with a young man of the name of Bland, who had for a time served under him, but had withdrawn himself with a hope that he would be permitted to live at home in peace; Fanning charged him with being a deserter, stabbed him several times with his sword, and then shot him, and after turning him over with his foot to see that he was dead, said the d—-d rascal would never deceive him again.”  "Fanning Loses the Bay Doe." (North Carolina State Archives) "Fanning Loses the Bay Doe." (North Carolina State Archives) In a better-remembered incident, “He and his raiders first rode to Col. [Andrew] Balfour's plantation. When they arrived, the Loyalists immediately opened fire. Absalom Autry fired at Col. Balfour and the shot broke his arm. Col. Balfour made his way back into the house to protect his daughter and his sister. The Loyalists rushed the house and pulled Col. Balfour away from the women, then riddled his body with bullets. Even Col. Fanning fired his pistol into Balfour's head. The women were kicked and beaten until they fled to the home of a neighbor.” Fanning left an account of his service, which includes interesting reflections of a loyalist in Canadian post-war exile. Like combatants everywhere, he had far more sympathy for his comrades than for his enemy. Reflecting on the fate of the loyalists he had commanded, he wrote, “Those people have been induced to brave every danger and difficulty during the late war, rather than render any service to the Rebels. .... As to place them in their former possessions, is impossible—stripped of all their property, driven from their Houses—deprived of their wives and children—robbed of a free and mild government—betrayed and deserted by their friends, what can repay them, for the misery? Dragging out a wretched life of obscurity and want, Heaven, only, which smooths the rugged paths, can reconcile them to misfortune. Numbers of them left their wives and children in North Carolina, not being able to send for them; and now in the West Indies and other parts of the world for refuge, and not returned to their families yet. Some of them, that returned, under the act of oblivion passed in 1783, was taken to Hillsboro, and hanged for their past services that they rendered the Government whilst under my command.” The Act of Pardon and Oblivion had been passed by the North Carolina legislature in 1783 to pardon most of the states citizens who had been Loyalists during the war. Some Loyalists were not eligible for pardon under the terms of the statute. Those who had become officers in the British Army were ineligible, as were those who had left the state with the British for more than a year. The act also made Tories who had committed "willful and deliberate murder, robbery and house-burning" ineligible. Fanning would therefore have been ineligible but, just to be sure, the law specifically excluded him and two others by name.  The grave of Andrew Balfour, murdered by Fanning in 1782 (months after the Battle of Yorktown). (randolphhistory.wordpress.com) The grave of Andrew Balfour, murdered by Fanning in 1782 (months after the Battle of Yorktown). (randolphhistory.wordpress.com) Fanning’s memoir begins with a scriptural citation. Quoting 1 Samuel 15:23, he writes, “Rebellion according to the Scripture is, as the Sin of Witchcraft; and the propagators thereof, has been more than once punished; which is dreadfully exemplified this day in the now United States of America but formerly Provinces; for since their Independence from Great Britain, they have been awfully and visibly punished by the fruits of the earth being cut off; and civil dissention every day prevailing among them; their fair trade, and commerce almost totally ruined; and nothing prospering so much as nefarious and rebellious Smuggling.” Indeed, the first years of Independence were messy. Even as Fanning was completing his memoir, the First Congress was meeting in New York under the new Constitution and working with the nation's first president to craft a more perfect union. A close read of 1 Samuel 15 puts Fanning’s scripture quote in context, providing food for thought. The full verse reveals that it is a king (Saul, the predecessor of King David) who has rebelled against the will of God. (I quote here from the King James version, the version Fanning would have read.) “For rebellion is as the sin of witchcraft, and stubbornness is as iniquity and idolatry. Because thou hast rejected the word of the LORD, he hath also rejected thee from being king.” This, at least to modern minds, turns the meaning of the verse on its head. However, Saul’s confession turns the meaning around one more time. “And Saul said unto Samuel, I have sinned: for I have transgressed the commandment of the LORD, and thy words: because I feared the people, and obeyed their voice. (1 Samuel 15:24) Kings owe their allegiance to God, not to the people. To Fanning, evidently, that was an important distinction. (Revised September 16, 2020) More from The 8th Virginia Regiment |

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed