Philadelphia and the nearby towns of Lewes and New Castle, Delaware were collectively the “Ellis Island” of the 18th century. Shiploads of German and Scotch-Irish immigrants docked at these towns. Under the care of Lutheran, Reformed, and Presbyterian churches the immigrants headed west toward the Pennsylvania frontier, passing through Downingtown, Lancaster and York on the road that is now (in most places) U.S. Route 30. It was typically in Lancaster, along the Conestoga Creek, that they were outfitted for the long trip. Lancaster’s German craftsmen provided “Conestoga” wagons and “Pennsylvania” rifles along with other supplies. (Wagon drivers frequently smoked cigars, hence the slang "stogie" from "Conestoga.")  The remains of "Fort Gaddis" in Fayette County, Pa. have been left to deteriorate. It was built about 1770 by Thomas Gaddis, the uncle of two 8th Virginia soldiers who lived nearby. William and Henry Gaddis served in Capt. Croghan's company. William died in service in 1777. The house was called a "fort" because Thomas was a militia leader and the house served as a rallying point. A liberty pole was erected here during the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion in defiance of federal power. A family property dispute has prevented the building's conservation. Despite its appearance, it is not too late to save it. (Wikimedia Commons) After Carlisle, the road turned south into the Cumberland Valley, through Western Maryland and into Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. From there it continued south all the way through Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina before terminating at Augusta, Georgia.

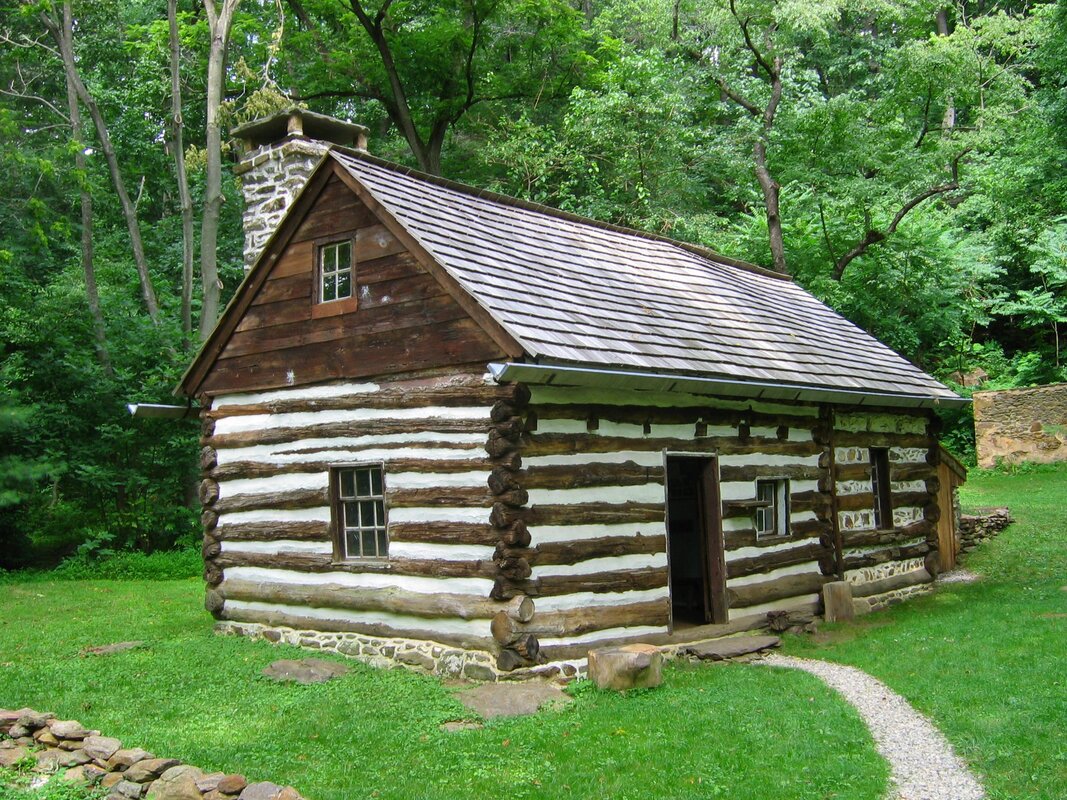

The settlers brought more than Conestoga wagons and Pennsylvania rifles with them. Perhaps the most enduring symbol of frontier life is the log cabin. This architectural marvel was first brought to America by the settlers of New Sweden—the short-lived colony of the Swedish Empire that preceded William Penn’s colony along the lower Delaware River. Many of the colonists were Finns (Finland was part of Sweden for centuries) who had grown up in log houses in the forests of Scandinavia. They were more comfortable in the forest than other early New World colonists and were among the first to venture inland. The log house is their contribution to American culture.

Read more: "A Frontier Cabin Restored" (8/15/17)

2 Comments

|

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed