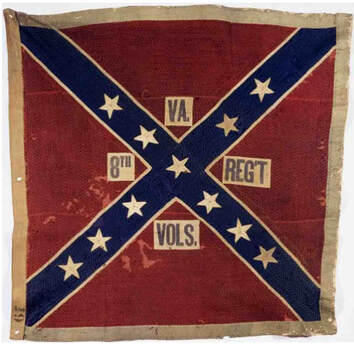

Battle flag of the "Bloody Eighth," also knows as the "Berkeley Regiment." Battle flag of the "Bloody Eighth," also knows as the "Berkeley Regiment." The designation “8th Virginia Regiment” was used three times in two wars for non-militia units: twice in the Revolution and once in the Civil War. The existence of three regiments of the same name sometimes causes confusion for researchers and genealogists. This confusion is exacerbated by the fact that two of them were recruited in overlapping territory and the third was recruited nearby. This post is intended to make it easy to distinguish among them, and to provide a little bit of service history. In the French and Indian War, Virginia had one "Virginia Regiment," notably commanded for part of the war by George Washington. The was (briefly) a 2nd Virginia Regiment, as well. In the Revolution, the Old Dominion had 15 numbered regiments. In the Civil War it had 64. The Original 8th Virginia, 1776-1778

Most of the men in the original regiment signed up for two-year enlistments that ended in the spring of 1778 at Valley Forge. That, combined with casualties and weak recruiting, left the regiment significantly understrength when it marched out of Valley Forge. At the Battle of Monmouth, it was provisionally combined with the 4th and 12th regiments, which were also understrength, as the “4th-8th-12th Virginia Regiment.” The 4th, the 8th, and the 12th had all served together in Charles Scott’s brigade since the spring of 1777. The “New” 8th Virginia of 1778-1779

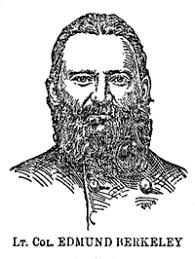

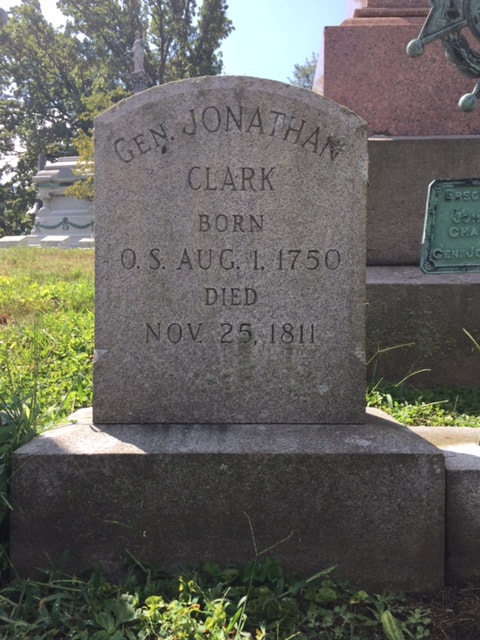

In October of 1777, after Germantown but before the Valley Forge encampment, George Slaughter was promoted to become the new major of the 12th Virginia. He had, up until that time, been a captain in the original 8th Virginia. He resigned in November to deal with a family emergency. In January, he was succeeded by Jonathan Clark, who likewise had until that time been a captain in the original 8th Virginia. When the 12th was redesignated in September of 1778, it’s field officers were Col. John Neville, Lt. Col. Charles Fleming, and Maj. Jonathan Clark. It continued in service until 1779 when the line was reorganized again. The Confederate 8th Virginia Another 8th Virginia Regiment was authorized by the Governor of Virginia in May of 1861 for service in the Confederate Army. It was led by Col. Eppa Hunton, Lt. Col. Charles Tebbs, and Maj. Norborne Berkeley. Major Berkeley was named in honor of Gov. Norborne Berkeley (1718-1770), a popular late-colonial governor. Berkeley, the regiment's best-remembered commander, was a graduate of VMI from Aldie, Loudoun County. Three of his brothers also served as officers in the regiment, leading it to sometimes be called the “Berkeley Regiment.” (It did not recruit in Berkeley County (named for the governor), as is sometimes assumed.) It was also called the “Bloody Eighth” because of its hard service. The Civil War 8th Virginia’s original companies and captains were Company A, the “Hillsboro Border Guards,” raised in Loudoun County and led by N.R. Heaton; Company B, the “Piedmont Rifles,” raised at Rectortown in Fauquier County and led by Richard Carter; Company C, the “Evergreen Guards,” raised in Prince William County and led by Edmund Berkeley; Company D, “Champe’s Rifles,” raised at Haymarket in Prince William County and led by William Berkeley; Company E, “Hampton’s Company,” raised at Philomont in Loudoun County and led by Mandley Hampton; Company F, the “Blue Mountain Boys,” raised at Bloomfield in Loudoun County and led by Alexander Grayson; G Company, “Thrift’s Company,” recruited at Dranesville in Fairfax County and led by James Thrift; H Company, the “Potomac Grays,” raised at Leesburg in Loudoun County and led by Capt. Morris Wampler; Company I, “Simpson’s Company,” raised at Mount Gilead and North Fork in Loudoun County and led by James Simpson, and Company K, “Scott’s Company,” raised in Fauquier County and led by Robert Scott.

In 1905, Edmund Berkeley wrote a poem to welcome Union veterans to a reunion at the Manassas Battlefield that is notable for the grace shown to men who had fired at him on that very field. It was published by the Society of the Army of the Potomac in the report on its fortieth reunion.

O Lord of love, bless thou to-day This meeting of the Blue and Gray. Look down, from Heaven, upon these ones, Their country's tried and faithful sons. As brothers, side by side, they stand, Owning one country and one land. Here, half a century ago, Our brothers' blood with ours did flow; No scanty stream, no stinted tide, These fields it stained from side to side, And now to us is proved most plain, No single drop was shed in vain; But did its destined purpose fill Of carrying out our Master's will, Who did decree, troubles should cease And his chosen land have peace; And to achieve this glorious end We should four years in conflict spend; Which done the world would plainly see Both sides had won a victory. And then this reunited land In the first place would ever stand Of all the nations, far and near, Or East or Western hemisphere. Brothers, to-day in love we've met, Let us all bitterness forget, And with true love and friendship clasp Each worthy hand in fervent grasp And in remembrance of this day Let one and all devoutly pray: That when our earthly course is run And we, our final victory won, Together we'll pass to that blessed shore That ne'er has heard the cannon's roar; And where our angel comrades stand To welcome us to Heaven's bright strand.

8 Comments

Though still insufficiently covered in classrooms, the Battle of Kings Mountain is recognized as the key event in the demonstration of popular southern refusal to submit to Loyalist rule. Even less well-remembered is the smaller Battle of Musgrove’s Mill, without which there may have been no Kings Mountain. It was a little encounter in which just 200 Patriot militiamen faced off against 264 Loyalist regulars and militia. Though small, it sent a strong signal that backcountry Americans simply would not be ruled any longer by a foreign king. Giving such small battles their due is the purpose of Westholme Publishing’s “Small Battles” series. The Battle of Musgrove’s Mill, 1780 comes from the pen of John Buchanan, the undisputed dean of southern Revolutionary War history. Now in his 90s, Buchanan writes as well as ever. In fewer than a hundred pages, he puts the story in context; explains the British, Tory, Indian, and Patriot perspectives; tells us about the key commanders on both sides; narrates the battle; and tells us why it matters. That is a lot to put into eighty-eight pages of text, but he has done it masterfully. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

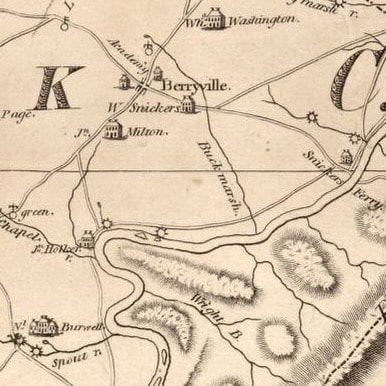

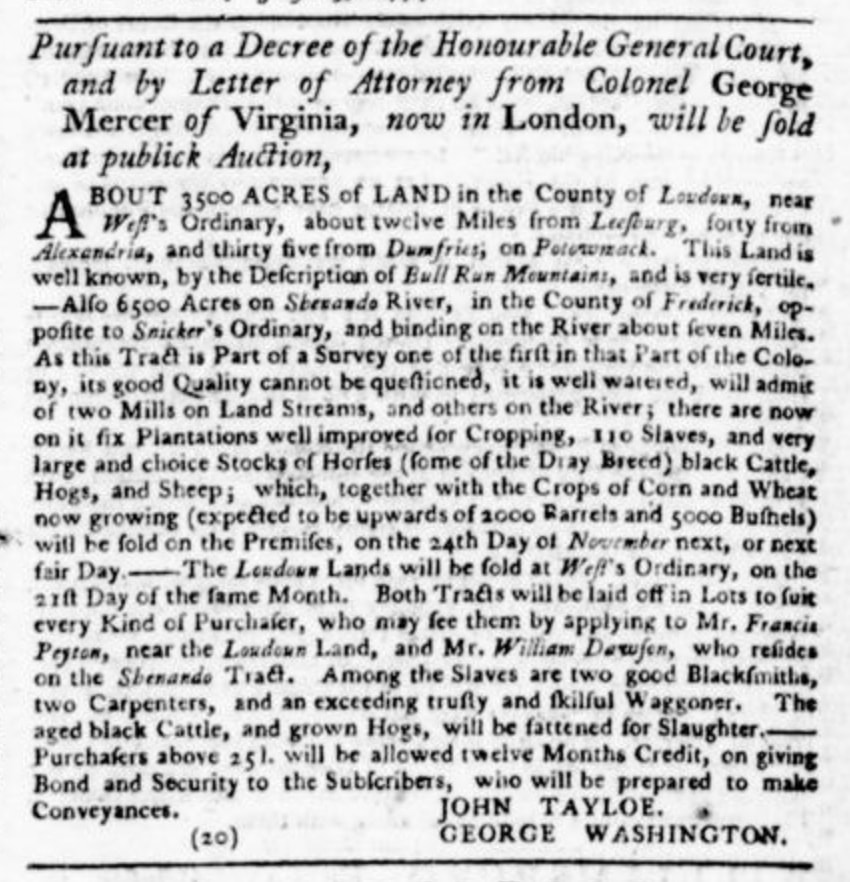

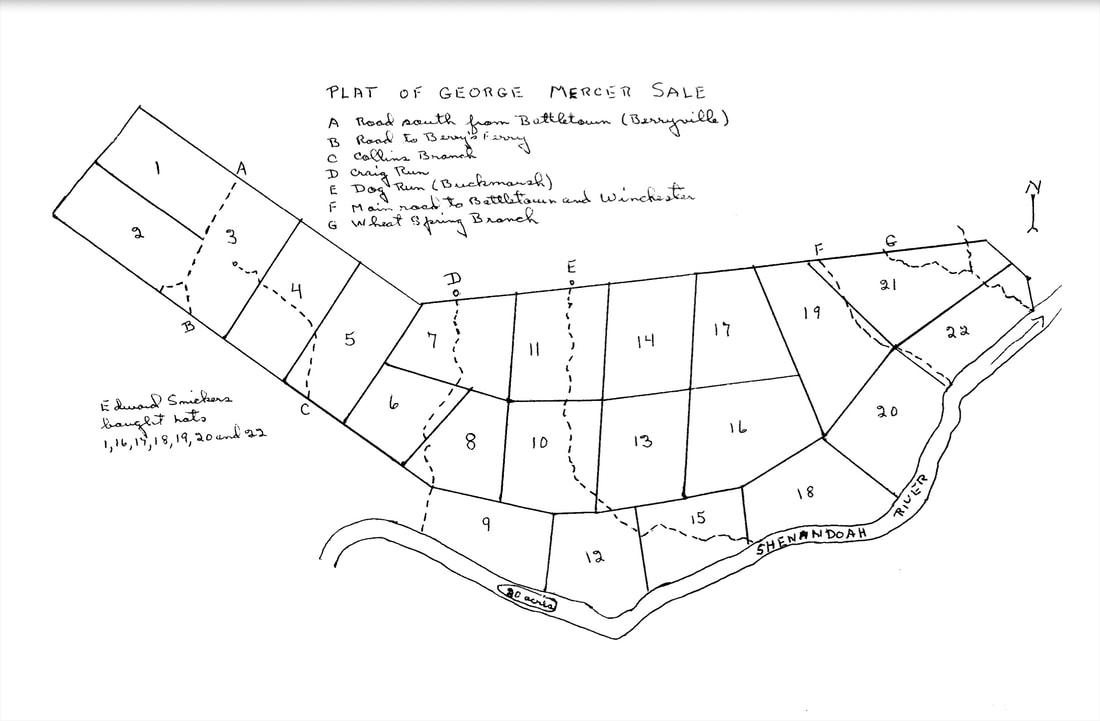

At the peak of his career, Mercer was selected by the Ohio Company of land speculators to represent their interests in London. The hated 1765 Stamp Act was enacted by Parliament while he was traveling. Not fully aware of sentiments at home, he accepted an appointment as Stamp Master for Virginia. He was overtaken by a mob and forced to resign when he returned to Virginia. Though the cheering crowd carried him out of the capitol in Williamsburg in celebration, Mercer soon left the colony for good.

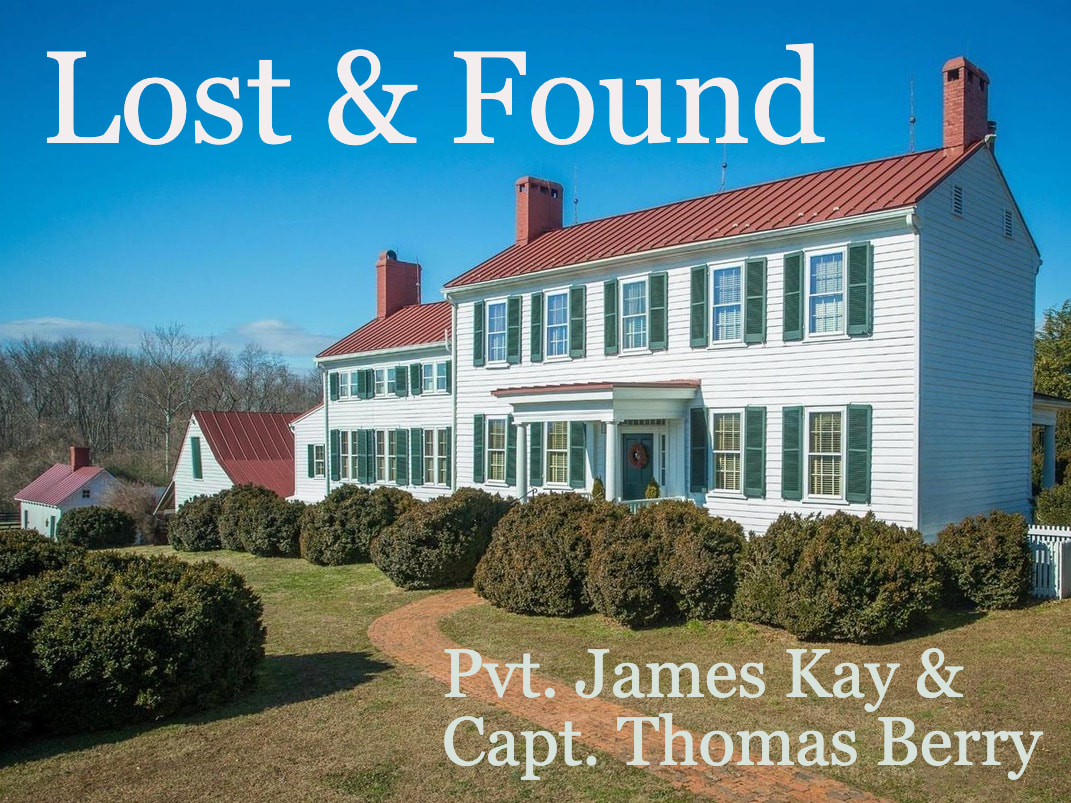

Less than two years later, the Frederick Committee of Safety chose Thomas to lead a new company of Provincial soldiers, which was then assigned to the 8th Virginia Regiment. He continued to lead his men until their enlistments expired at Valley Forge in April of 1778 and then returned home to lead what appears to have been a quiet life. He died in 1818. Benjamin, the older brother, was the founder of Berryville—a town just north and west of the old Mercer property. Benjamin is better remembered because of his namesake town, but Thomas’s military service deserves to be remembered as well. Read More: "Lost & Found: James Kay & Thomas Berry" More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

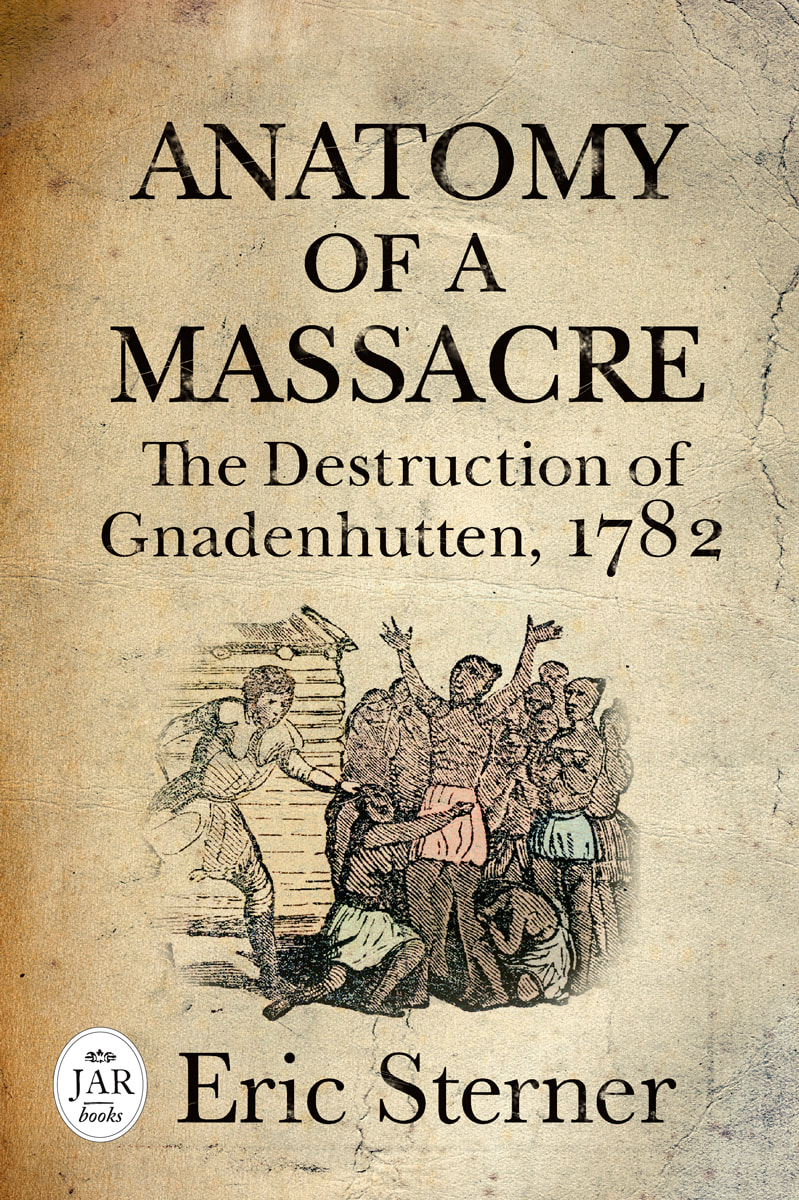

Lord de la Warr’s name appears frequently in Mr. Sterner’s story. His name was given to the Delaware River, which in turn lent its name to the Lenape people who have long been known to English speakers as the Delaware Tribe. Mr. Sterner has provided the definitive account of the worst atrocity of the Revolutionary War. In 1782 more than eighty white settlers clubbed, killed, and scalped ninety-six peaceful, Christian Indians as they prayed and sang hymns. The attack on the Moravian mission town of Gnadenhutten (Ohio) was intended as both a punitive and preemptive strike, conducted by settlers whose families and farms had been targeted by other Indians acting as proxies of the British. It is a horrific story that has defied understanding until now. ...continue to Emerging Revolutionary War Era. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

Washington was born on February 11, 1731…under the Julian Calendar. This was the old calendar established under Julius Caesar. Pope Gregory moved the Catholic world to a more accurate calendar in 1582, but Protestant England, under Queen Elizabeth, wasn’t bound by the change. Leap year differences put Britain and the America colonies eleven days behind the rest of the western world. Moreover, New Year’s Day was March 25 under the old calendar, not January 1. Consequently, when the British Empire finally changed to the Gregorian Calendar in 1752, Washington’s birthday changed from February 11, 1731 to February 22, 1732. Both dates are correct, but the proper way to note the Julian date is “February 11, 1731 (O.S.).” The abbreviation stand for “old style.” Washington’s Birthday was declared a holiday by Congress in 1879. Many people don’t realize that Congress has no authority to declare holidays (days off) for anyone other than federal employees and residents of the District of Columbia. States, however, followed the federal government’s lead and Washington’s Birthday was celebrated for decades on February 22. Abraham Lincoln’s birthday was never a federal holiday, but was celebrated by many states on February 12—just ten days before Washington’s birthday. In the 1950s, there was an effort to establish a third holiday, President’s Day, to honor “the office of the presidency” on March 4 – the original day of quadrennial inaugurations. Though some states adopted the new holiday, Congress declined to in the belief that three holidays in rapid succession were too many.

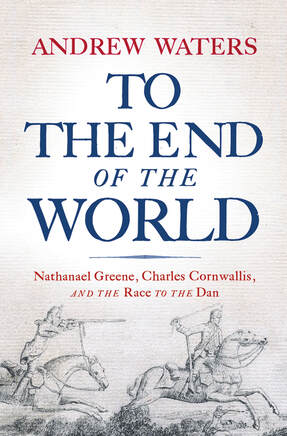

Under our present Constitution, the United States has had forty-five presidents. Some have been great and some have not. Reputations have waxed and waned as attitudes change and new biographies are written. Celebrating “President’s Day” seems to make no more sense that celebrating “Congress Day” or “Supreme Court Day.” In the fact, the notion of a “President’s Day” has vaguely monarchist overtones. Surely, we can all think of several presidents who don’t deserve the honor. Washington, however, stands high above the rest. He is rightly known as the father of the country. He effectuated a great break with the past, establishing durable and free government in part by repeatedly declining to cling to power. Only one other president rivals his claim to greatness. Holidays have always been the subject of civic activism. Veterans Day was moved back to November 11 in 1975 to align with the World War I armistice. Columbus Day has been replaced by “Indigenous People’s Day” in Florida, Hawaii, Alaska, Vermont, South Dakota, New Mexico, and Maine. If you live in a place (such as, believe it or not, Washington State) that celebrates “President’s Day,” you might want to call your state legislator and point out that Chester Arthur doesn’t belong on the same holiday stage as George Washington. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment “In a place like Salisbury,” writes Andrew Waters of the North Carolina town that witnessed the 1781 Race to the Dan, “you can live among its ghosts and still not know it’s there.” Enthusiasts know that this is true of many Revolutionary War sites, including some of real importance. Mr. Waters complains in his book To the End of the World: Nathanael Greene, Charles Cornwallis, and the Race to the Dan of the simplified understanding most Americans have of the Revolutionary War. “For most of us, the story of the American Revolution is of George Washington and the minutemen, Valley Forge and Yorktown.” In our Cliffs Notes version of history, many places, heroes, and even whole campaigns are left out. Like most of the war in the south, the Race to the Dan is overshadowed by Yorktown. The mere fact that George Washington was not a participant relegates the story to a second-tier status. The Race, however, holds unique challenges for the historian and the storyteller. It occurred over more than two hundred miles, depending on how you count it, rather than at one identifiable spot. Nathanael Greene’s genius is to be found in his mastery of logistics and strategy, which are subjects that make many people’s eyes glaze over. Though heroic and difficult, it was still a retreat and retreats don’t lend themselves to celebration. Its significance is not so much in what it achieved but rather in what it made possible, which requires detailed explanation. Consequently, the Race to the Dan has been given short shrift for more than two centuries. It is mentioned in the war’s histories, but almost never in detail. In writing this book, Mr. Waters was determined to correct that and he has succeeded. One can’t resist noting the appropriateness his name: the waterways of the Carolinas play a central role in the story. He makes plain from the beginning that the story is personal to him. He is a conservationist and doctoral candidate in South Carolina who has made a career of conserving the Palmetto State’s watersheds. “Rivers are my business,” he says at the very beginning of the book. He also plainly declares, “We all need heroes, and . . . Greene has become one of mine.” ...Continue to The Journal of the American Revolution. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

William Croghan has never been famous, but his life illustrates the aspirations and achievements of America’s early frontiersmen. He fought for national expansion and then played an important role in that expansion by moving to Kentucky and running the office that parceled out bounty land to veterans. This was a lucrative position. Croghan prospered and built a stately home, which he called Locust Grove. ...continue to The Journal of the American Revolution. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

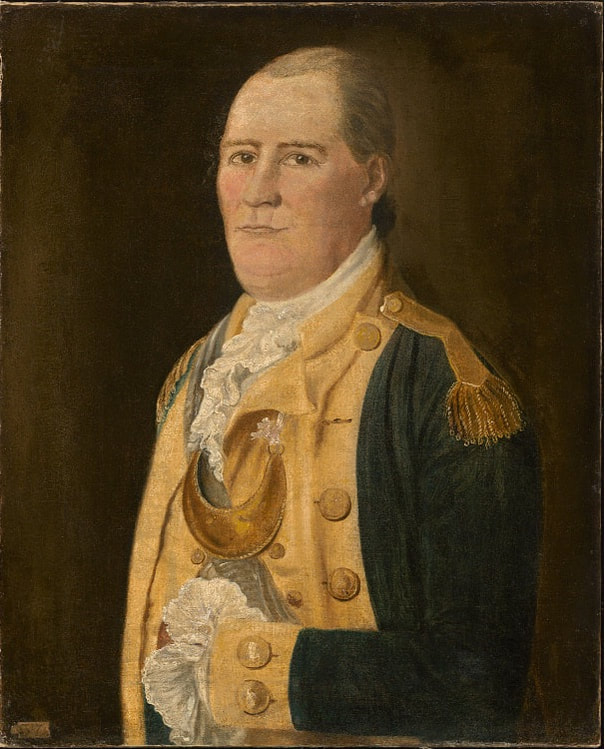

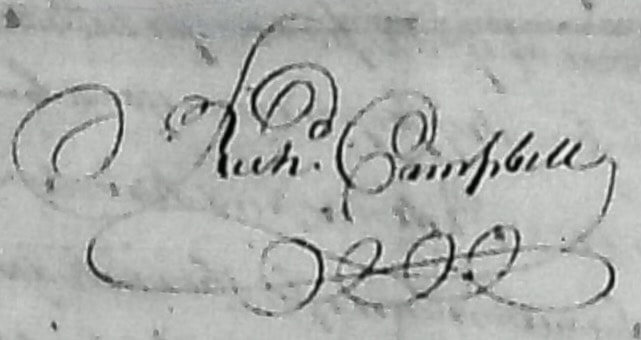

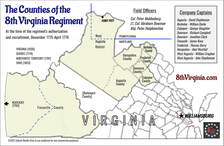

Cuppy was born near Morristown, New Jersey on March 11, 1761. While still an infant, he was brought to Hampshire County, Virginia by his German parents. Their new home was on the South Branch of the Potomac River near the town of Romney, which is now in West Virginia. About forty miles west of the Shenandoah Valley, this was the very edged of settled Virginia territory. John was just fourteen years old when the war began—too young to be a candidate for service when Hampshire was directed to raise a rifle company in July of 1775. He was still too young when Dutch-descended Capt. Abel Westfall recruited a company there that winter for Col. Peter Muhlenberg’s new 8thVirginia Regiment. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment (Image: Randy Steele) (Image: Randy Steele) As an old man, Daniel Anderson wanted to spend his last years in prayer. He said he would “ever pray for the success and prosperity of his native state and country.” He would pray “to secure the liberties of which in his younger days he voluntarily encountered the perils of war and shed his blood in her service.” These were not platitudes. The bloodshed was real and there is no reason to doubt that his prayers were just as authentic. He was a humbled man. He was disabled by his war wounds and obliged to use the few resources he had caring for his wife and three physically and mentally handicapped adult children. Surprisingly, the unique contours of Anderson’s war service resolve a persistent question. The men of the 8th Virginia fought almost everywhere during the Revolution. I have sometimes described them as having served “from New York to Georgia,” but wished I could say “from Canada to Florida.” The regiment didn't range that far, but I have long suspected that some of its men did over the course of the war. The Florida question remains unsolved. In 1776, Maj. Gen. Charles Lee took the regiment south to attack the Tory haven at St. Augustine. They made it to Sunbury, Georgia before the expedition was called off. The malaria-stick regiment was posted there at Fort Morris, on the Medway River, for some time. Did they ever cross the St. Mary’s River into what was then the colony of East Florida? The governor of Florida reported in October of 1776 that “depredations were made by the Rebels as far [across the border] as Saint John River,” forcing him to commandeer a boat for defense. The main body of the 8th Virginia was probably gone by then, but had any of them gone scouting across the river before the raid? Quite a few men also remained behind to recover from sickness and some--like William Gillihan and Collin Mitchum--transferred to the 5th South Carolina Regiment. Did any 8th Virginia men participate in the foray to the St. John’s River that summer or fall? Probably. Maybe. We may never know.  Daniel Anderson enlisted twice under Daniel Morgan, portrayed here in an anonymous portrait from about 1780. Daniel Anderson enlisted twice under Daniel Morgan, portrayed here in an anonymous portrait from about 1780. The Canada question, on the other hand, is now settled. The very first companies of Congress-authorized “Continental” troops included two companies of riflemen raised in the Shenandoah Valley in July of 1775. I have hoped to find just one 8th Virginia soldier who was in Capt. Daniel Morgan’s Frederick County company. But was there one? Yes. Daniel Anderson enlisted in Morgan’s rifle company in July of 1775 and was with him at Boston and the attack on Quebec. He was wounded at Quebec in the chest and the right arm, captured, and held prisoner for months. He was eventually exchanged and then discharged at Elizabeth, New Jersey. In February 1777 he enlisted again under Morgan, who was now the colonel of the 11th Virginia. There is no record of Anderson in the 11th Virginia rolls, however, because he was promoted to sergeant and transferred into Capt. Thomas Berry’s company of the 8th Virginia. Anderson was with the 8th through Germantown, Whitemarsh, Valley Forge, and Monmouth. He was discharged on February 2, 1779. He then received a state commission as a lieutenant in the Western Battalion of Virginia state troops (state regulars—not militia and not Continentals), probably fighting Indians as far west as Indiana under Col. Joseph Crockett. Other 8th Virginia men were on the frontier as well, serving as far west as Illinois. After the war, Anderson settled in Shenandoah County, Virginia and lived the rest of his life there. So what can we claim for the length and breadth of the regiment’s service? “From Canada to Florida” is still a stretch beyond what we can prove. To the Florida line? Still too far. Until we can prove more, we’ll have to settle for “From Canada nearly to Florida.” Can we also say, “From the Atlantic to the Mississippi?” Not yet, but it’s entirely plausible. Regardless, the range of the 8th Virginia’s men is impressive. Almost all of that movement was covered on foot. In retirement, Daniel Anderson’s wounds kept him from performing hard labor—even the work of a subsistence farmer. Still, he somehow had to support his wife and three disabled children. “I am by occupation a farmer,” he said in 1820, “but owing to wounds and age I am unable to follow it. I have my wife living with me, aged 57 years; 1 daughter, aged 23 years, a cripple; and two dumb children, both simple, one a girl aged 14 the other a boy aged 27. The reason for his older daughter’s disability was her being “so much afflicted with Cancers that she has not been out of the house for 16 months.” The word "dumb" in those days still meant "mute." "Simple" meant intellectually disabled. There were no federal pensions yet, but he applied to the Virginia legislature for pension on the basis of his own service-connected disability. He made his case before a judge. His conclusion was recorded by the court in the third person: “The prayer of your petitioner therefore is that your honorable body will pass an Act allowing such pension as in your wisdom you may deem sufficient to enable him to end his few remaining days in praying, as he will ever pray for the success and prosperity of his native state and country to secure the liberties of which in his younger days he voluntarily encountered the perils of war and shed his blood in her service.” The date of his petition isn’t shown, but it was supported by notes from doctors and a letter from Daniel Morgan in 1796: “The bearer of this Dan’l. Anderson Inlisted a soldier with me in the year 1775 march’d with me to Boston & from thence to Quebec – was with me in the storm of the garison, on the last Day of Dec’r. when Gen;l Montgomery fell. He Rec’d two wounds in the action, one in the Breast & one in his Arm which Doctor senseny & Doctor Balwin certyfies that said wounds has so disabled him as to Rendered unfit for Hard Labour & thinks Him a proper object for a Pension.” "Doctor Balwin" was Cornelius Baldwin, the former surgeon of the 8th Virginia. Anderson received his state pension and later received federal support as well. He died on November 6, 1840. UPDATE: Thanks to Carolyn Brown Butler who alerted us to the pension of her ancestor William Smith. Smith, after his time in the 8th, served under George Rogers Clark and (former 8th VA captain) George Slaughter. He was sent by Clark as an express rider to the Iron Banks, six miles below the mouth of the Ohio on the Mississippi. So now we can say that at least one 8th Virginia man served from "the Atlantic to the Mississippi." More from The 8th Virginia RegimentThere is no dignity in being forgotten. A case in point is Virginia Lt. Col. Richard Campbell, a Continental officer who died bravely for his country but lies today in an unmarked grave far from his home. “Killed near the end of the battle at Eutaw Springs,” wrote the authors of a 2017 study of that battle, “he is virtually unknown today.” In his own day, however, Nathanael Greene called him a “brave, active, and intrepid Soldier.” Light Horse Harry said he was an “excellent officer” who was “highly respected and beloved.” In 1832 one of his soldiers still remembered him as “the brave Col. Campbell.” Dick Campbell, as he was known, deserves to be remembered. Little is known of his early life. Historian Louise Phelps Kellogg asserted a century ago that he was “a distant relative of the Campbell family of southwest Virginia.” This would tie him to militia Gen. William Campbell, a leader at the Battle of King’s Mountain. He was evidently born in Virginia about 1730 and raised in Dunmore (now Shenandoah) County, where he was appointed a sheriff’s deputy in 1772 and reappointed in 1774. The Shenandoah Valley was culturally distinct from the eastern parts of Virginia. Many of Campbell’s neighbors were Germans who had migrated from Pennsylvania.

More from The 8th Virginia Regiment |

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed