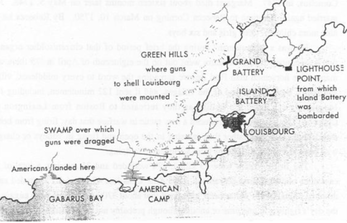

Multiple conflicts occurred in the pre-Revolutionary northeast, including such little-remembered wars such as King William's War, Queen Anne’s War, and Father Rale’s War. Louisbourg was (and is) positioned on the east coast of Cape Breton and directly east of the modern state of Maine, which was then part of Massachusetts. Louisbourg itself was a threat to New England: it was a center for privateering and well positioned to interfere with New England’s economically crucial fishing industry. At the start of King George’s War (known in Europe as the War of Austrian Succession) in 1744, a Franco-Indian force raided and destroyed the British fishing village at Canso, in nearby Nova Scotia. In 1745, Massachusetts Governor William Shirley organized a response. Militia from Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire set off on an expedition supported with funds and supplies from Rhode Island, New York, and Pennsylvania. While there were no professional soldiers involved, the force did have support from the British Navy. The Fortress of Louisbourg was thought to be impenetrable from the sea. A land approach, however, provided hilly terrain that allowed for the erection of siege batteries. After a siege of several weeks and a number of raids and skirmishes, the fortress surrendered on June 27, 1745. While the French forces had suffered from poor morale and other issues, the stark fact remained that American militia had taken on and defeated a professional army sheltered in a major fortification. This was well enough remembered that in 1774, the First Continental Congress noted in its Address to the People of Great Britain that it was "chiefly by" the "vigorous efforts" of the people of Massachusetts that "Nova-Scotia was subdued in 1710, and Louisbourg in 1745."

While the British army was humiliated, Washington’s own reputation for heroism was bolstered, in part because of his own reports. “I luckily escaped without a wound,” he wrote, “though I had four bullets through my coat, and two horses shot under me.” Louisbourg (1745), Monongahela (1755), and the outbreak of the Revolution itself in 1775 are milestones in the colonists’ increasing confidence in their own military capabilities. Though Louisbourg was remote from Virginia, it was not remote from those who began the war in Massachusetts. Braddocks’ defeat was very much front-of-mind to all Virginians at the start of the war. This must have been especially true for men like the 8th Virginia's Maj. Peter Helphenstine and Capt. Thomas Berry of Winchester (Washington's headquarters during the French and Indian War) and Captains John Stephenson and William Croghan who filled their companies with men from the settlements near the site of the general’s failure.

This elevated view of their militias’ capabilities must be viewed as an important factor in the colonists’ decision to take up arms against the Crown. It is even more important in view of the prevalent Anglo-American dislike of standing or “regular” armies. Oliver Cromwell had used his “New Model” army to rule by martial law. King James II had attempted to use a standing, professional army to restore the monarchy’s supremacy over parliament. For this is he was deposed and replaced by William and Mary, who accepted a Declaration of Rights (enacted as a “Bill of Rights” in 1689) that specifically forbade standing armies on British soil in peace time.

"Also we do ... DECLARE ... that all and every the Persons being our Subjects, which shall dwell and inhabit within every or any of the said several Colonies and Plantations, and every of their children, which shall happen to be born within any of the Limits and Precincts of the said several Colonies and Plantations, shall HAVE and enjoy all Liberties, Franchises, and Immunities, within any of our other Dominions, to all Intents and Purposes, as if they had been abiding and born, within this our Realm of England, or any other of our said Dominions." Among the 27 indictments against the King in the Declaration of Independence was the charge that “He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.” When the war began, it was a war between American militia and British regulars. While some might have seen this as an uneven fight, many more saw it as proof of the justice and moral superiority of the American cause.

More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

1 Comment

Al Underwood

4/24/2022 12:42:21 pm

Great work!!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed