|

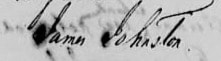

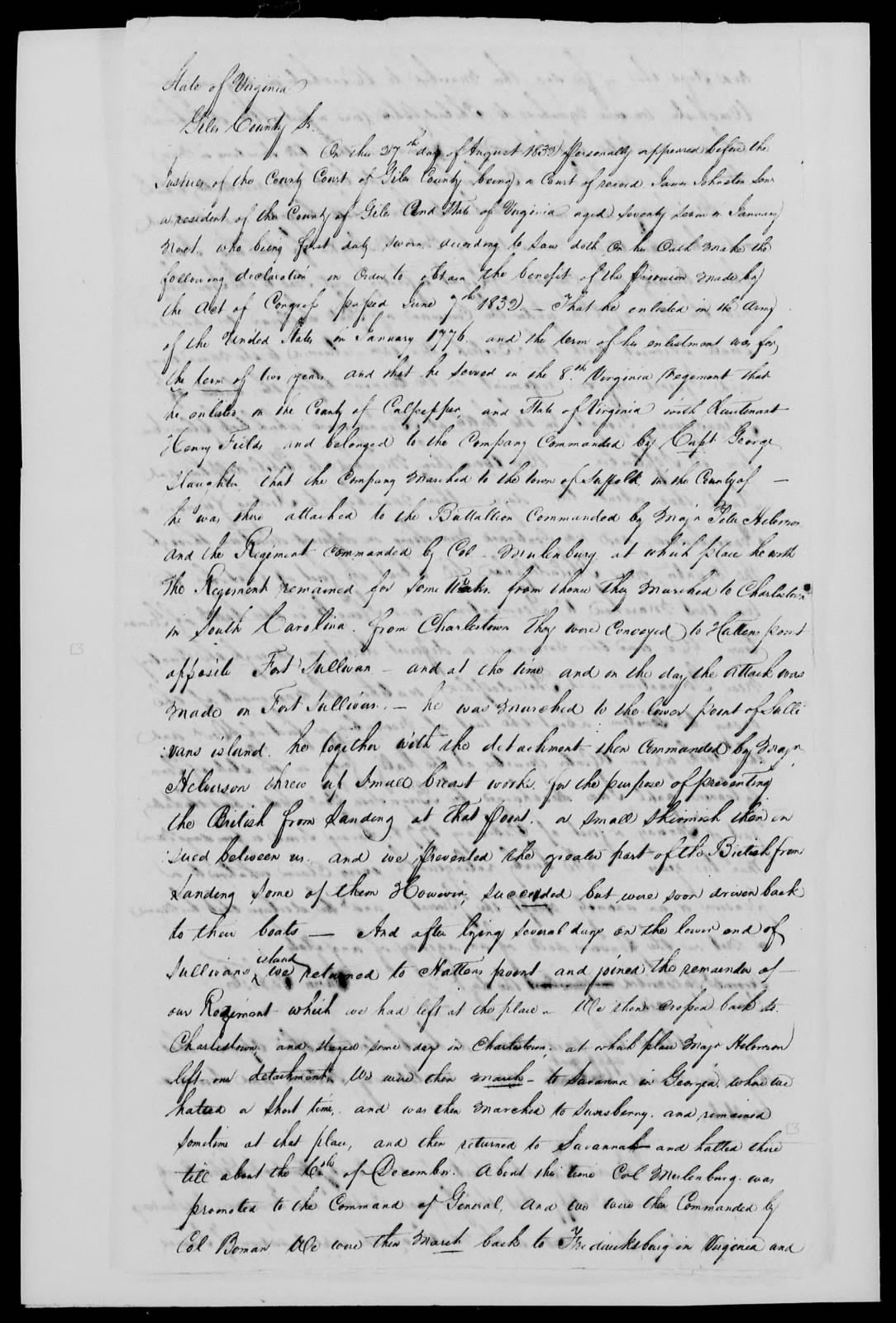

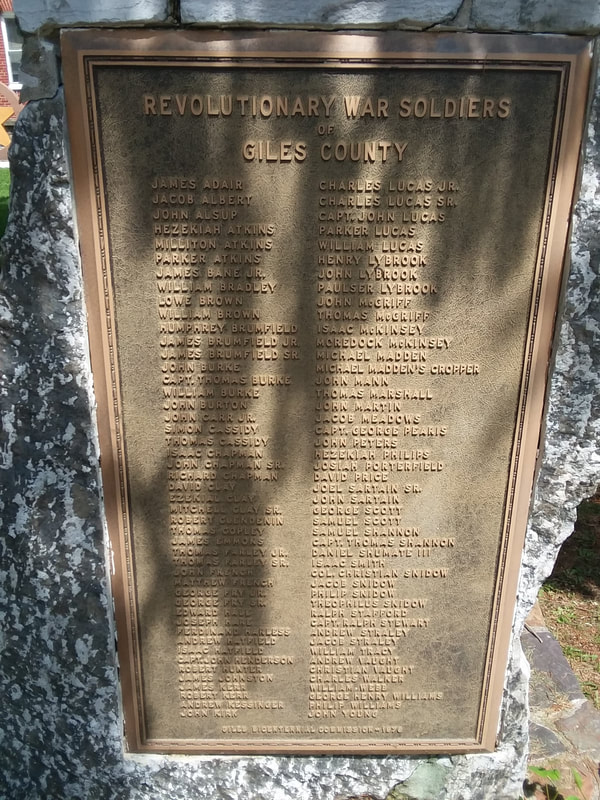

The narrative that was submitted with veteran James Johnston’s 1832 pension application provides a uniquely clear summary of the 8th Virginia Regiment’s service. The text of it, as transcribed by C. Leon Harris, is presented below with the Harris annotations removed and new explanatory notes by Gabe Neville inserted in italics. New paragraph breaks have been introduced along with a handful of changes to capitalization and punctuation for clarity. Otherwise, the complete text is presented unaltered. Pension Application of James JohnstonState of Virginia Giles County Ss.

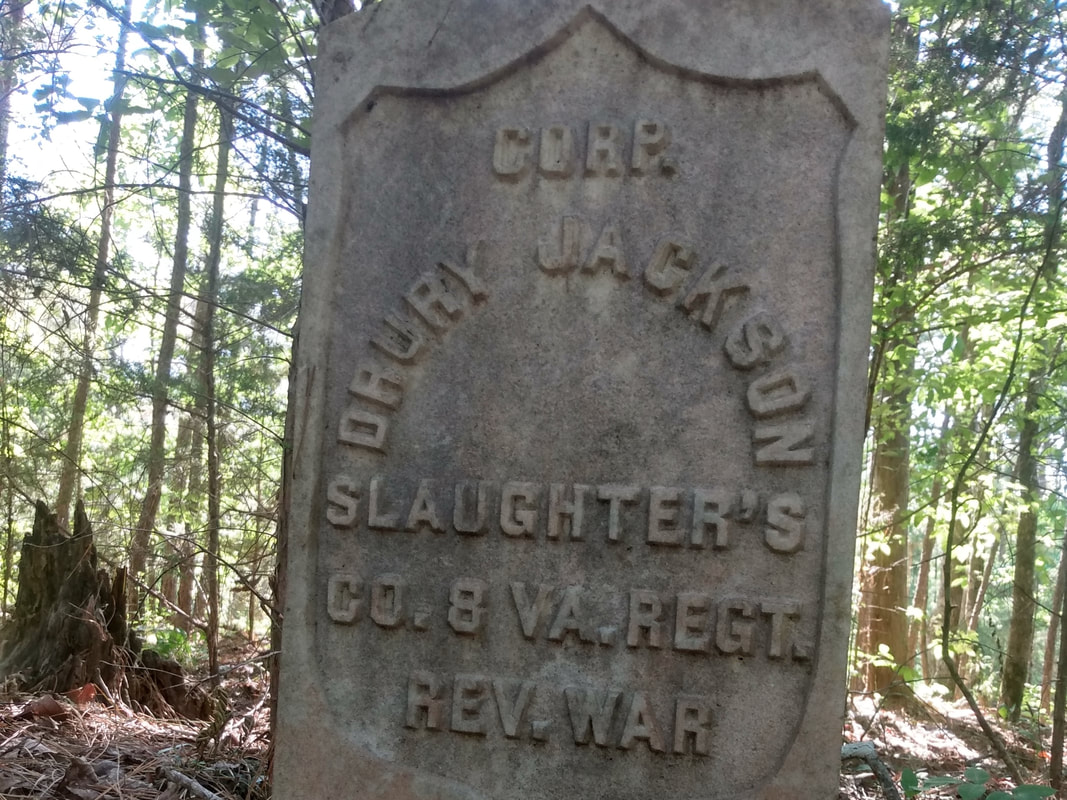

That he enlisted in the County of Culpepper and State of Virginia with Lieutenant Henry Fields and belonged to the Company Commanded by Capt George Slaughter. ◊ Each company officer had an enlistment quota to meet in order to get his commission. Family and friends made the best prospects. Lt. Field was Capt. Slaughter’s wife’s cousin. Her brother and two other cousins were also in the regiment, as was Capt. Slaughter’s nephew, Lawrence Slaughter. The five men from the Abbott family who enlisted in the company were probably Johnston’s cousins. That the Company marched to the town of Suffolk in the County of ______. He was there attached to the Battallion Commanded by Maj’r Peter Helverson and the Regiment commanded by Col Mulenburg at which place he with The Regiment remained for some weeks. ◊ Suffolk, a little west of Norfolk, was the designated rendezvous point for the regiment. Suffolk was then in Nansemond County. Battalions were sometimes divisions of regiments, but in the Continental Army were almost always functionally synonymous with regiments. Johnston was detached at least once with Helphenstine, which probably explains his characterization. From thence they marched to Charleston in South Carolina. From Charleston they were conveyed to Hattens point opposite Fort Sullivan—and at the time and on the day the attack was made on Fort Sullivan, he was marched to the lower point of Sullivans island. He together with the detachment then commanded by Maj’r Helverson threw up small breast works for the purpose of preventing the British from Landing at that point. A small skirmish then ensued between us and we prevented the greater part of the British from Landing. Some of them, however, succeeded but were soon driven back to their boats. And after lying several days on the lower end of Sullivans island we returned to Hattens point and joined the remainder of our Regiment which we had left at the place. ◊ The regiment left with Maj. Gen. Charles Lee for South Carolina in May, arriving in June. “Hattens Point” is Haddrell’s Point between Charleston and Sullivan’s Island. A number of 8th Virginia men reinforced South Carolina troops on the north end of Sullivan’s Island to fend off an enemy crossing of the “Breach Inlet” while enemy warships bombarded Fort Sullivan (later Fort Moultrie) on the south end. Most accounts discount the action at the Breach Inlet as insignificant, summarizing that the British had misgauged the depth of the water and failed to cross. Johnston, however, indicates that the enemy made a concerted effort to cross and that some succeeded before being driven back.

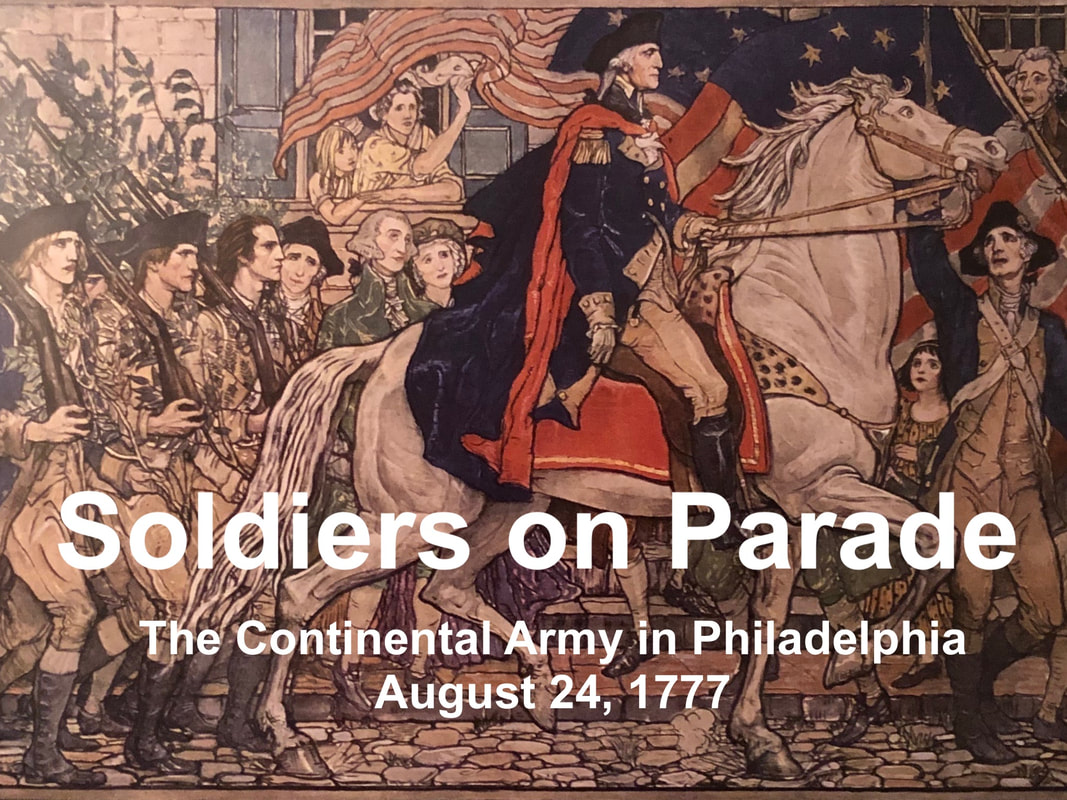

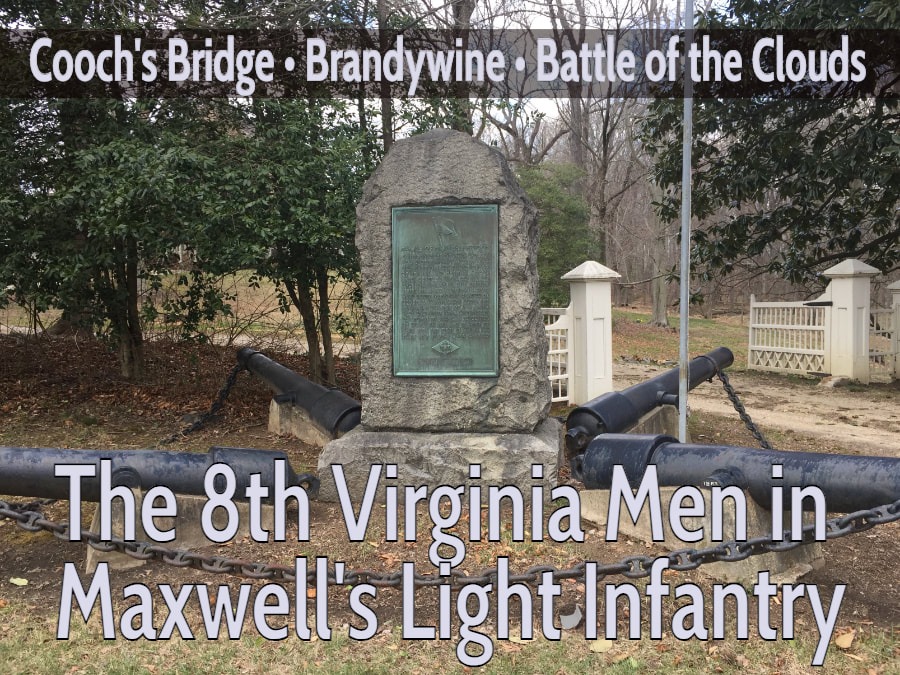

About the time Col Mulenburg was promoted to the command of General, and we were then Commanded by Col Boman We were then march back to Fredericksburg in Virginia and stayed there a few days then marched to Winchester in Virginia. ◊ Col. Peter Muhlenberg was promoted to brigadier general in February 1777, after which Lt. Col. Abraham Bowman was promoted to colonel. The return to Winchester allowed most of the soldiers an opportunity to visit their families. From Winchester we were marched to Philadelphia (and a part of the detachment who was inoculated for the small pox remained there till sometime in May). ◊ The entire Continental Army was inoculated early in 1777. Soldiers who had previously had the disease were exempt. We were then marched to Bonbrook or Middlebrook not recollected which in New Jersey and was attached to Gen’. Scotts brigade, and continued with the Main Army commanded by Gen’l Washington for some time. ◊ The regiment began collecting together at Boundbrook, N.J. in April and then moved to the camp at Middlebrook on May 25. It was assigned to Brig. Gen. Charles Scott’s brigade, along with the 4th Virginia, the 12th Virginia, Grayson’s Additional, and Patton’s Additional regiments. Scott’s brigade was one of two that made up Maj. Gen. Adam Stephen’s division. I was then attached to a Company of Light infantry and sent to the Iron hills near the head of Elk under the Command of Genl. Sullivan we had a small skirmish with the British. We then returned to the main army and I joined my own regiment on the Evening before the battle of Brandywine. I fought in the battle of Brandywine which took place some time in September. ◊ On August 28, each brigade sent picked men to form a light infantry battalion under Brig. Gen. William Maxwell, who Johnston misidentifies as John Sullivan. Maxwell’s Light Infantry existed for one month and fought in Delaware at Cooch’s Bridge (Iron Hill) on Sept. 3 and Brandywine in Pennsylvania on Sept. 11. “Head of Elk” is now Elkton, Maryland. Johnston reports that he returned to Capt. Slaughter’s company before Brandywine, but does not state the reason. We were then marched to Philadelphia and stayed there about two days – then marched to Riding furnace in Pennsylvania and was continued marching in different directions through the country near Philadelphia til about the first of October. ◊ After Brandywine, the army retreated to Chester, Pa. and then crossed the Schuylkill to Philadelphia before heading west along the river to block the enemy from crossing it. The Schuylkill was the last natural barrier between the British and Philadelphia, the seat of Congress. After the “Battle of the Clouds” ended in a torrential downpour, Washington’s army was rested and re-equipped at Reading Furnace, in northwest Chester County (not to be confused with the city of Reading, which is twenty miles to the north). After a feint, the British made it across and took Philadelphia. We were then marched to Germantown and I fought in the battle of German town. ◊ The Battle of Germantown occurred on October 4. A chance for victory was ruined in part because of a friendly fire incident between General Scott’s brigade and Anthony Wayne’s Pennsylvania brigade. Maj. Gen. Adam Stephen was blamed for it. Stephen was cashiered and replaced with the Marquis de Lafayette. We were then marched in different directions through the country near Germantown and Philadelphia watching the movements of the enemy til sometime about the last of November or first of Dec’r and then took up our Winter quarters at the Vally forge in the state of Pennsylvania until I was discharged by Brigadier Gen’l Scott about the Latter part of January or first of February 1778. having served a few days more than two years. ◊ After Germantown, the army camped at three different places northwest of Philadelphia before a series skirmishes known as the Battle of Whitemarsh early in December. The army then went into winter encampment at Valley Forge on December 19. Johnston’s two-year enlistment expired on January 26, 1778 but he reports remaining a little longer. He hereby relinquishes every claim whatever to a pension or an annuity except the present and he declares that his name is not on the pension roll of an agency of any state.  James Johnston Except for those who had reenlisted, all of the remaining original 1776 recruits left the regiment during the Valley Forge encampment. Efforts to recruit back to full strength after the southern expedition had fallen short and the regiment was never again back to even half strength. The three Virginia regiments in Scott’s brigade were merged into one unit known as the “4th-8th-12th Regiment” for the Battle of Monmouth in June, 1778. In September, the regiment was folded into the 4th Virginia and ceased to exist. The 12th Virginia was then renumbered and became the “new” 8th Virginia, which causes confusion for genealogists, particularly because many of the men came from the same parts of Virginia. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

1 Comment

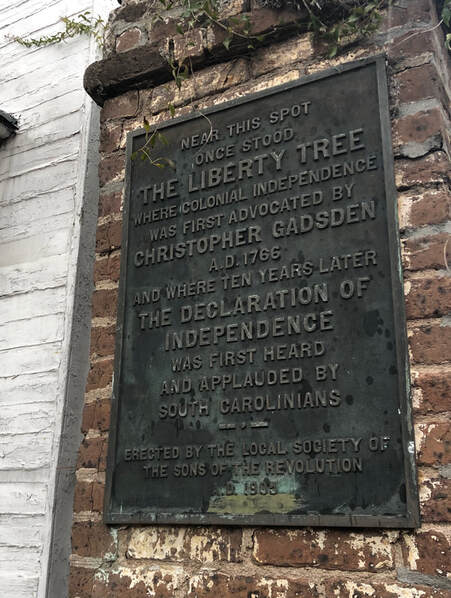

Mosquitos are nothing new to South Carolina. In 1774 a resident called them “devils in miniature.” In 1776, Col. Peter Muhlenberg's soldiers had to contend with them and didn't have the option of going indoors. In May of that year, the regiment rushed south from Virginia to help defend Charleston. They were part of a small army led by the strict and sardonic Maj. Gen. Charles Lee. On their arrival, Capt. Jonathan Clark spent much of the first week staying at the home of Christopher Gadsden. Gadsden was a prominent South Carolina Patriot and an early champion of Independence. Clark initially camped in Gadsden’s garden, but recorded that upon the “arr[ival] of [the] Moschetto” he got up and moved “in the House.” Enlisted men didn't have the option.

Though they fended off the British, many of them lost their battle with the mosquitos. Unlike the mosquitos bothering Tony Melton in 2015, the mosquitos of 1776 were active malaria vectors. By the start of August, nearly one hundred and fifty 8th Virginia men were too sick to continue south with General Lee into Georgia for a planned attack on West Florida. Most of the men who did continue were soon also sick. The army stopped its march in Sunbury, Georgia. South Carolina's Col. William Moultrie recorded that several men were buried there each day. The mosquitos paid no attention to rank. Colonel Muhlenberg got it and would never fully recover. Major Peter Helphinstine got it and was so sick he was forced to resign his commission and died a slow death at home in Virginia. The regiment was ordered back to Virginia in the fall, significantly depleted. Malaria was endemic to South Carolina and neighboring states until the 1950s. Its eradication is something of a mystery but may be connected to the invention of air conditioning, which prompted people to spend more time inside during the summer. Still, it continues to kill millions every year in Africa and other developing parts of the world. (Based on an earlier post.) More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

Time changes things. Neither the lake nor the woods were there when Drury Jackson died. Back then the grave was on cleared ground overlooking the Oconee River. Depressions in the soil still reveal to the trained eye that Drury was buried in proper cemetery. The river became a lake in 1953 when it was dammed up to create a 45,000-kilowatt hydroelectric generating station. When Dutch found the grave, the cemetery had been neglected and reclaimed by nature. Today it is in a copse of trees surrounded by vacation homes. Dutch spends his free time studying local history and conducting archeology. He has made some important finds, including a string of frontier forts along what was once the “far” side of the Oconee. He’s pretty sure that Drury’s burial in that spot is an important clue to his life in the years following the Revolutionary War. From there, however, things get complicated. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

Could the abolition of American slavery have come sooner? Maybe. Slavery never existed in the New World without someone also speaking out against it, and antislavery views took a demonstrably large leap forward during the founding era. Christianity, social contract theory, and the very spirit of the Revolution led many Americans to the same conclusion. Even many slaveowners understood it was wrong. “I can only say,” wrote George Washington about slavery in 1786, “that there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it.” Thomas Jefferson memorably condemned slavery in his first draft of the Declaration of Independence. While this language was removed by Congress, Jefferson really did want to effect a change. His concurrent draft of a Virginia constitution would have decreed, “No person hereafter coming into this country shall be held in slavery under any pretext whatever.” A decade later, he wrote that“The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other. Our children see this, and learn to imitate it; for man is an imitative animal.” His concern was not just for Virginia’s children: And can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are the gift of God? That they are not to be violated but with his wrath? Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep forever: that considering numbers, nature and natural means only, a revolution of the wheel of fortune, an exchange of situation is among possible events: that it may become probable by supernatural interference! The almighty has no attribute which can take side with us in such a contest. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

This was evidently true despite the absence of two complete companies. Lee may have extrapolated to account for the absent companies. Alternately, at least one of the present companies (Captain Jonathan Clark’s) appears to have enlisted numbers beyond its quota. When Muhlenberg set off on May 13, Capt. James Knox’s southwest (Fincastle County) company had not yet arrived. It was close, though—probably at Williamsburg. Or perhaps it had just arrived and needed to rest. Lee wrote, “Capt[ai]n Knox will follow the Regiment, so the Colonel must not wait for him.” Capt. William Croghan’s Pittsburgh (West August District) company, however, was even farther behind. Lee took the regiment anyway. There was no time to spare. Consequently, it would be an entire year until Croghan’s men joined the regiment. Lee wrote to John Hancock, “As the Enemy’s advanced Guard…is actually arrived—I must, I cannot avoid detaching the strongest Battalion we have to [North Carolina’s] assistance; but I own, I tremble at the same time, at the thoughts of stripping this Province of any part of its inadequate force.” Battalions and regiments were essentially synonymous at this time. Lee was, in fact, calling the 8th Virginia the “strongest” of the province’s nine regiments. He would later confirm this assessment when he wrote to Muhlenberg, “You were ordered not because I was better acquainted with your Regiment than the rest--but because you were the most compleat, the best arm’d, and in all respects the best furnish’d for service.” To Congress he reported, “Muhlenberg’ s regiment wanted only forty at most. It was the strength and good condition of the regiment that induced me to order it out of its own Province in preference to any other.”

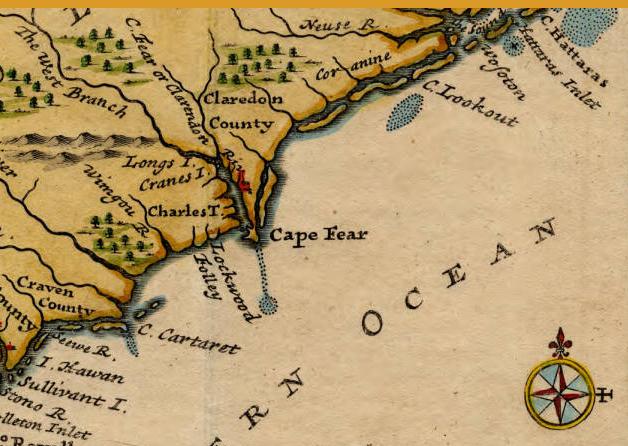

Meanwhile, the British commanders were learning that the Patriot victory at Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge had quelled their hoped-for Tory uprising. They opted, therefore, for an alternate target. Just as the 8th Virginia arrived at Cape Fear, the enemy was sailing off for Charleston, South Carolina. Muhlenberg’s men continued the chase, now at a forced-march pace. A very difficult and deadly summer lay ahead of them. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

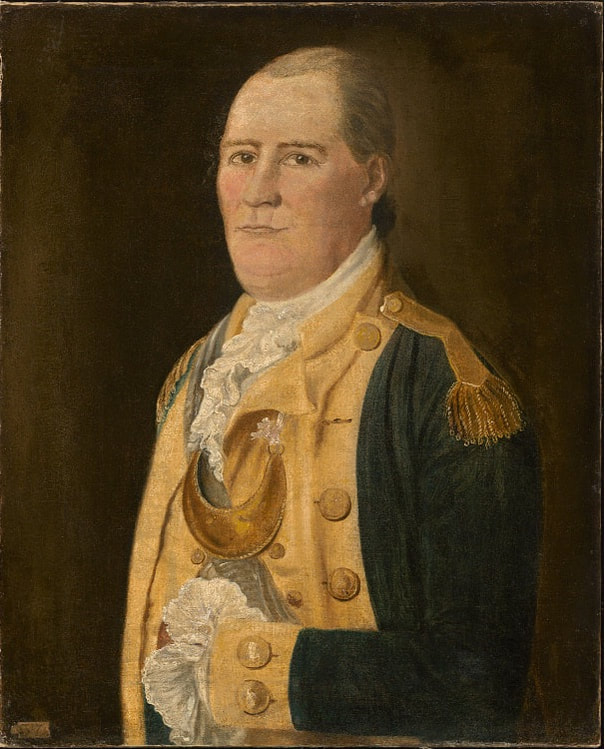

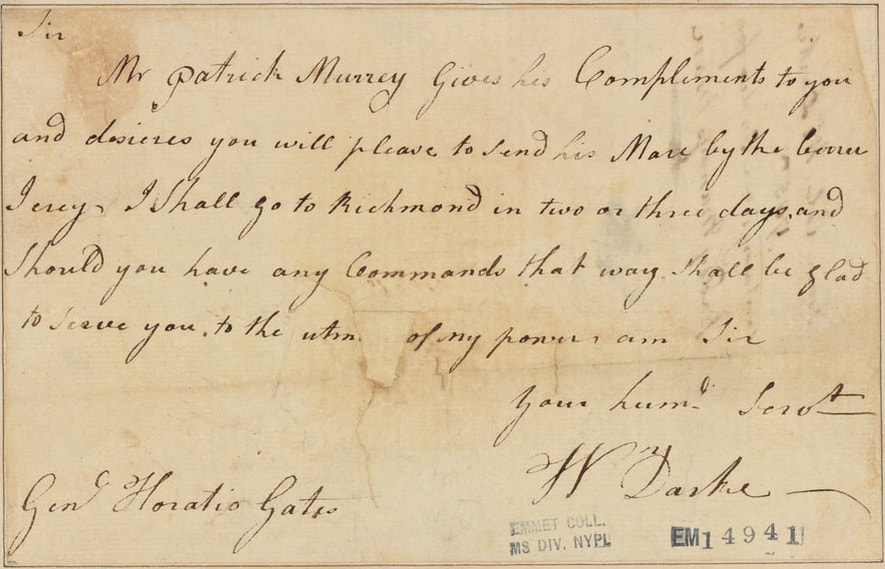

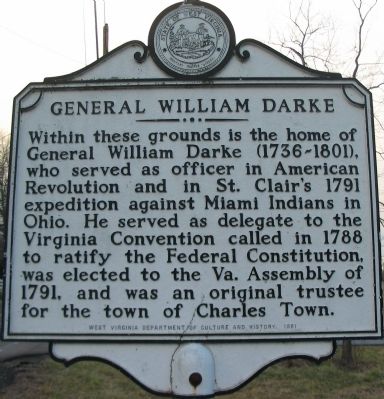

Darke and Washington had much in common. They both grew up in Virginia on the south bank of the Potomac River in Lord Fairfax’s vast proprietary lands. They were both physically large men and belonged to the same generation, born just four years apart. They were both veterans of the French and Indian War and they both committed themselves to the War for Independence in 1775.[2] There was much that separated them as well, including seventy-five miles of river between their homes. Wealth, education, social standing, and military rank all put the colonel below the future president. Their personalities were almost opposite—Darke had that “fire and rashness” while Washington was famously patient and reserved. Washington was refined, while Darke was described as having “unpolished manners.” Nevertheless, war, business, and politics bound them together off and on throughout their adult lives.[3] The French and Indian War They first encountered each other during the French and Indian War. Washington established his military reputation in Major General Edward Braddock’s disastrous expedition to Fort Duquesne in 1755. Darke’s earliest biographer dedicated nearly a fifth of his 1835 essay to describing the expedition and its outcome, asserting that in “the nineteenth year of his age” Darke “united himself to the army under the ill-fated Braddock.” The biographer, who is identified only as “a Citizen of Frederick County, Maryland” may have known Darke. A Charlestown Free Press account cited in (and published sometime before) an 1858 Harpers New Monthly Magazine article asserted that Darke “was one of the Rangers of 1755 (then nineteen years old), serving under Washington, in Braddock’s ill-managed march toward Fort Duquesne.” The idea that Darke was with Washington under Braddock has been doubted by some, including Shepherdstown historian Danske Dandridge. She, in 1910, acknowledged the tradition but made a point of saying she had “seen no proof.” Supporting the tradition, however, is Darke’s own statement in a 1791 letter to President Washington that he had “bean in the Service of my Country in allmost all the wars Since the year 1755 in one Capassoty or other.”[4]

Darke’s French and Indian War service evidently concluded in 1759; Washington’s ended the year before. They had both gained valuable military experience. Still in their twenties, they now focused on their domestic lives. Washington married Martha, the widow of Daniel Parke Custis, in January of 1759 and spent the next fifteen years at Mount Vernon. Darke also married a widow, Sarah Deleyea, whose husband had been scalped and killed by Indians while sleeping under an elm tree. Darke and Washington both raised the sons of other men. Unlike the Washingtons, however, the Darkes also had four children of their own. Nothing else is known of Darke’s life in the 1760s other than an unsupported 1888 assertion that he “was engaged in defending the Virginia frontier against the incursions of the savages.”[7] The Revolution The Upper Potomac region responded enthusiastically to the call for troops in 1775. Among the first units to be authorized by Congress was Hugh Stephenson’s company of riflemen from Berkeley County, which competed with Daniel Morgan’s Frederick County company in a race to Boston. Two more companies were raised across the river in Frederick County, Maryland. At the same time Virginia organized two regiments of provincial regulars, some independent companies for the defense of the frontier, and a network of minute battalions. When six more regiments were authorized by the Commonwealth in December, Darke was ready to go with a company of men. It became the first newly-created company of the 8th Virginia Regiment of provincial regulars and he was commissioned to be its captain.[8]

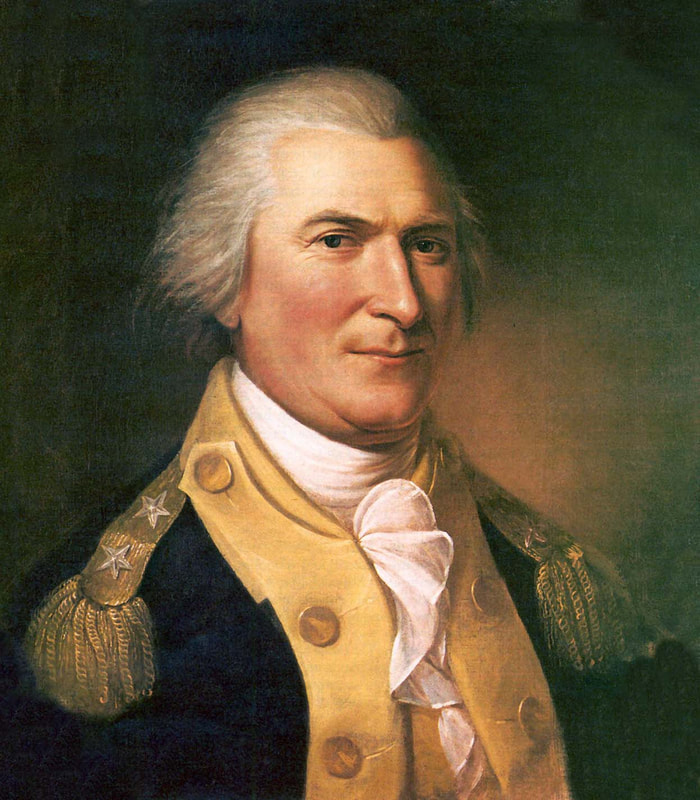

The regiment’s rendezvous point was Suffolk, a choke point in Virginia’s terrain between Williamsburg and Tory-dominated Norfolk. In the spring of 1776, they kept watch over Tories and stopped slaves from joining Governor Dunmore’s army of Loyalists. After the arrival of Major General Charles Lee, commander of the Southern Department, they marched south to protect Charleston, South Carolina. Darke’s men were present for (but probably not directly engaged in) the Battle of Sullivan’s Island on June 28. Other 8th Virginia men helped fend off an enemy landing on the north end of the island but they were not involved in the famous defense of Fort Moultrie at the island’s southern end. After they fended off the British a greater danger appeared: malaria. Most of Muhlenberg’s men had no resistance to it. As he headed farther south to attack Florida, Lee left a large group of sick men behind in Charleston. The advance never made it past Sunbury, Georgia. According to an 1802 account, “The troops that went to Georgia, suffered exceedingly by sickness; at Sunberry, 14 or 15 were buried every day, till they were sent to the sea Islands, where they recruited a little.” Darke lost nearly half his company to the disease.[9] Among the first to get sick was 8th Virginia major Peter Helphinstine, who returned home to Winchester and died. On the day the army marched south from Charleston, Lee appointed Captain Richard Campbell to replace Helphinstine. In doing so, he passed over Darke, who was the senior eligible captain. No reason is given in the record, but the best explanation is that Darke was sick, left behind, and perhaps not expected to recover. Congress confirmed Campbell’s new rank.[10] The promotion became a source of controversy when the regiment returned to Virginia and Campbell began to oversee recruitment for the 1777 campaign. Unable to address the matter himself, Muhlenberg appealed to Washington for help. An aide de camp responded to him, writing, “Congress having confirmed Majr Campbell in his Office, leaves his Excellency no power to remove him, but for the Commission of some Offence.”[11] Controversies related to rank and promotion were common in the Continental Army. Muhlenberg himself was made a brigadier general at this time, which caused problems of its own. Darke’s case was handled delicately. On May 13, Congress gave Washington the authority to look into Darke’s case and resolve it. Explicitly authorized to make the decision, Washington promoted Darke to major. For purposes of seniority, the promotion was made retroactive to January 4, but its effective date was delayed until the end of September. This was evidently Washington’s way of looking out for a trusted soldier and compensating Darke for an injustice. Major Campbell kept his rank but was transferred to another regiment.[12] While the controversy was sorted out, Darke was put on detached duty, sometimes performing jobs that might have been assigned to a major. In June, Washington put Darke in command of 150 Virginia riflemen alongside General Anthony Wayne and Colonel Daniel Morgan. They harassed the enemy as Howe withdrew from New Jersey and they were centrally engaged in the Battle of Short Hills.[13] When Howe’s army sailed away, Washington sent Morgan’s Rifles, an elite unit, north to join the forces under Major General Horatio Gates opposing British General John Burgoyne. Howe, however, was headed in the opposite direction. When that was discovered, Washington rushed his army south and on August 28 ordered his brigades to each supply 117 of their most capable men to form a new light infantry force under the command of New Jersey’s General William Maxwell. Specifically, each brigade was to provide“one Field Officer, two Captains, six Subalterns, eight Serjeants and 100 Rank & File.” William Darke was chosen for this service by General Charles Scott, his brigade commander, possibly at Washington’s direction. Maxwell’s Light Infantry was the sole Continental unit at the Battle of Cooch’s Bridge and played an important role on both sides of the river at Brandywine a week later.[14]

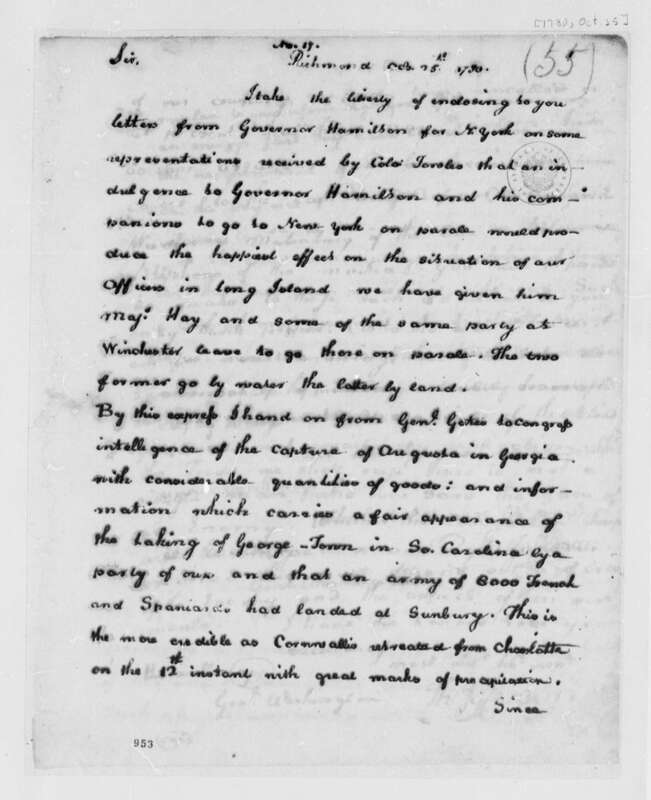

In May of 1780, Darke and other captive officers wrote to Governor Thomas Jefferson asking for financial support. The only thing of real value Virginia could offer them was tobacco, which the prisoners could barter with or sell. Jefferson wrote to Washington, who was encamped near New York, advising him that the Virginia legislature had authorized a shipment of tobacco for the prisoners and asked him to see if the British would allow it. If not, the tobacco was to be sold for hard money, which would then be sent to the men. Washington advised that the latter course would have to be followed. [17] The general and the governor were both interested in getting Darke and his comrades home, perhaps on parole (honor bound not to fight) or properly exchanged (free to take up arms again). Jefferson had the necessary leverage. In February, 1779 Virginia state troops had captured Henry Hamilton, the lieutenant governor of Quebec and the Crown’s superintendent of Indian affairs. Based at Fort Detroit, Hamilton had been in command of British military efforts in the northwest and was hated by Virginia frontiersmen. On October 25, 1780 Jefferson played this valuable card. Hamilton and a few other British prisoners were traded for several American officers on Long Island. At last, Darke was free. Washington wrote to Congress that a total of fifteen American officers were on their way home. “The Military Chest being totally exhausted,” he wrote, “they will with difficulty be enabled to get as far as Philada. I must solicit you to procure them a supply there, sufficient to carry them home. Their long and patient sufferings entitle them to attention and to every assistance in getting themselves and Baggage forward.”[18]

Things escalated significantly in May when Lord Charles Cornwallis invaded Virginia and occupied Richmond with a large army. The Virginia legislature fled to Charlottesville, but was pursued by Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarlton’s dragoons. The alarmed legislature appealed to the recently-promoted General Daniel Morgan for help. The hero of the Battle of Cowpens (January 17, 1781) had returned home to Winchester suffering from sciatica and other ailments. Governor Jefferson wrote to him on June 2, urging him to raise an army in the Shenandoah Valley and come to the commonwealth’s rescue. Morgan agreed, but found men reticent to leave home as the harvest season approached. This led him to “call on the best aid I could possibly get” in convening a group of “Gentlemen who I esteem of most influence.” This group met on June 15 to plan and prepare. Among them were General Gates, Lieutenant Colonel Darke, and a handful of other prominent military men from Frederick and Berkeley counties. [20] They set about recruiting men to defend the Commonwealth, urging the legislature to “provide some decisive measure for procuring the number necessary.” Properly equipping the recruits also proved challenging. At last, Morgan and Darke arrived with reinforcements on July 7, the day after the Battle of Green Spring. Morgan’s health, however, soon forced him to return home again. For the time being, the Americans remained in camp near Williamsburg while Cornwallis established a base at Yorktown. Meanwhile, the French persuaded Washington that there was an opportunity in Virginia, and they proceeded south with the main army from New York.[21] Washington arrived in Williamsburg on September 14. The troops formed up so he could review them. Many or most of these soldiers had never seen the great general before. The following day the officers lined up to greet Washington at a reception. It may have been at this event that Darke inappropriately “made the first motion” to the commander-in-chief. It was George Bedinger, one of Darke’s captains, who wrote, “I have never been able to account for such a motion. I suppose it was the Colonel’s usual fire and rashness, and, that Washington perhaps had a desire to know what the enemy would do on such an occasion. It was in my opinion an extraordinary and, I think unnecessary temerity.” Darke may simply have been eager to express his gratitude for his freedom.[22]

Business and Politics After the war, Colonel Darke focused on his home and his family. He and his wife raised their own four children, an older son from Sarah’s first marriage, and a local orphan. In addition to whatever farming he engaged in, Darke made forays into both business and politics. He was now a man of stature in his community.[24] He became deeply involved in America’s first interstate public works project, working closely with (and for) Washington. As the Kentucky country filled up with settlers, it became apparent that there were economic, political, and strategic imperatives for connecting the Ohio watershed with the east. For Kentuckians, it was significantly easier to transport goods down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers to Spanish New Orleans than it was to transport them upstream and overland to ports on the Atlantic coast. To counteract this, there was intense interest in creating a junction between the Ohio and Potomac Rivers via the Monongahela and Youghiogheny rivers. Success would keep Kentucky tied to the United States and keep the value of its produce headed east.[25]

In 1789, the river was sufficiently clear for Darke to make news in Richmond’s Virginia Gazette and Weekly Advertiser. We cannot but congratulate our readers on the fair prospect of Patowmack, becoming soon the common channel of conveyance for the produce of the fertile country through which it runs. The water carriage is already so far established, that five wagons are kept constantly plying between waters’s branch, the common landing, of George-Town. Colonel Darlk’s boat last week, brought down a load of 262 barrels of flour from Shepherds-Town, in Virginia, and passed Shanandoah and Seneca Falls, with safety and ease.[27] Ultimately, the project was unsuccessful. Dry weather left the river impassible while too much rain flooded the bypass “canals.” The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal was later built to replace it (on the other side of the river). Even that canal never connected the Potomac and Ohio rivers.[28] Washington’s other great project during this period was the drafting and ratification of the United States Constitution. The proposal was controversial in Virginia, with leading figures like Patrick Henry and George Mason opposed to it. A convention was called to ratify (or reject) the document and Darke was elected to be one of two delegates from Berkeley County. His partner was retired Major General Adam Stephen, who had ordered Darke into the fog at Germantown. Both of them supported the Constitution, prevailing in an 89 to 79 vote.[29]

After taking office, President Washington signed legislation authorizing the location of a new capital city on the Potomac River “at some place between the mouths of the Eastern-Branch and Conogocheague.” In other words: somewhere between Georgetown (then in Maryland) and Williamsport (still in Maryland), an 85-mile stretch of river. In October of 1790, Washington visited Shepherdstown and met with Darke and other locals to discuss the possibility of locating the capital at Sharpsburg—just across the river. He also visited Hagerstown and Williamsport, but ultimately selected the Georgetown location.[31] War with the Indians In 1791, Darke was elected to the Virginia General Assembly. His time in that office was short, however, because Washington had other plans for him. Rapid settlement of Kentucky had enraged Indians in Ohio who used Kentucky as their hunting grounds. By one account, as many as 1,500 settlers were killed over a period of just a few years. A campaign against the Indians in 1790, led by Brigadier General Josiah Harmar, had been a failure. An earlier campaign under Colonel William Crawford had resulted only in the colonel’s capture, brutal torture, and execution. Shortly after Darke’s election, he received a letter from President Washington asking him to lead a regiment of “levies” in a major new campaign. Levies were federal soldiers on short-term (six month) enlistments. Washington asked Darke to “appoint from among the Gentlemen that are known to you, and who you would recommend as proper characters, and think likely to recruit their men, three persons as Captains, three as Lieutenants, and three as Ensigns in the Battalion of levies to be raised in the State of Virginia, for the service of the United States.”[32]

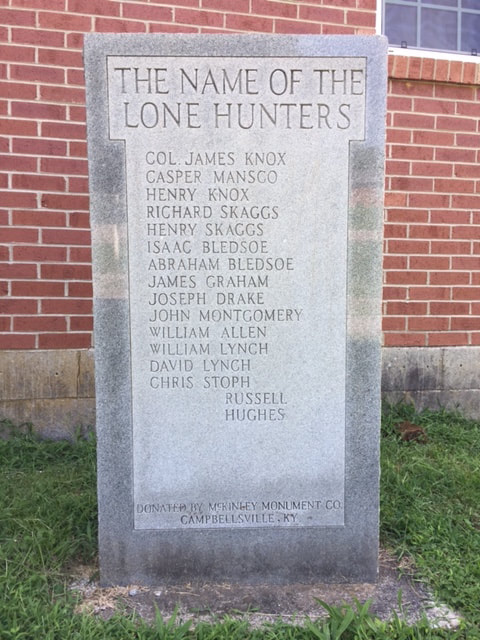

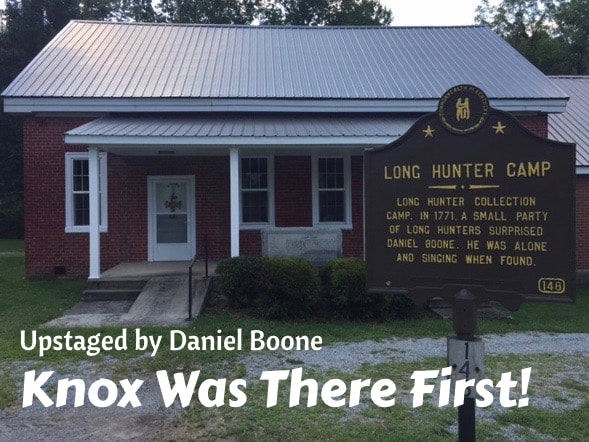

The advance looked much like General Braddock’s march of 1755, and concluded much the same way. They cut a road through the wilderness as they went, needing it to run a supply train. Insufficient supplies, poor morale, expiring enlistments, bad weather and bickering officers all contributed to a horrific defeat on November 4. Surrounded, General St. Clair’s army—camp followers included—was sniped at and then butchered to pieces by the Indians as men fled in panic back down the road. Their flight was made possible by a desperate charge through the Indian lines led by Colonel Darke. General Butler and Darke’s son were both among the hundreds of dead who made up the largest loss for any U.S. Army in any war before the Battle of Shiloh in 1862.[34] Though painfully wounded in the leg, Darke was the only senior officer to survive the massacre with both his life and his reputation intact. This was in part because of his conduct and in part because he sent his own report on the battle to the President in a letter he made sure was public. This enabled him to influence public perception of the disaster before any investigations or recriminations began. In his letter to Washington Darke was critical of General St. Clair but placed the greatest blame on Major John Hamtramck of the 1st U.S. Regiment, whom he openly accused of cowardice. Two months later, on his way home, he sent a blistering criticism of St. Clair to a member of Congress who leaked the letter to the press.[35] Darke wasn’t just playing the blame game. He was angry and he was grieving. His son, Joseph, died “after twenty-seven days of unparalleled suffering.” Another of Darke’s three sons, John, died shortly after the colonel returned home from the battle. John’s death was probably a coincidence, but at least one historian seems to have interpreted it as another battle casualty. Darke’s old French & Indian War commander, Robert Rutherford, reported the second death to President Washington in March. “I Indeed sympathize Very tenderly with him on the death of his sons,” he wrote, “as that of his youngest was followed by the death of his eldest son, a few days after his return home and who left a small family.”[36] St. Clair’s terrible defeat was the subject of the first Congressional oversight investigation. Darke left home for Philadelphia in mid-March and testified against St. Clair. The general was exonerated, but his reputation never fully recovered. Darke also visited the president during this trip and had a private conversation with him about the next campaign. Washington asked Darke for his views on who should command. Darke recommended Daniel Morgan, Charles Scott, and Henry Lee—all Virginians. Darke did not realize, and Washington did not say, that for political reasons the commander could not be a Virginian. Lee, known as “Light Horse Harry” from his service in the Revolution, was well regarded but had only been a lieutenant colonel in the Revolution. Washington said he was concerned that officers, including Darke, who had outranked Lee would refuse to serve under him. Washington pressed Darke on the question. Darke does not seem to have given a clear answer, which apparently confirmed the president’s view. Washington, however, told Darke that he had a high opinion of Lee, and Darke left with the impression that Lee was going to get the job.[37] Darke then spoke separately with Secretary of War Henry Knox, who was less guarded and told Darke that Lee would not get the job. Darke thought he knew otherwise and that Knox was wrong. Darke later admitted to Lee that he didn’t give a clear answer to Washington about the rank issue. “I did not answer though I Confess I think I Should,” he wrote in a letter. He blamed it on “being so distressed in mind for Reasons that I need not Mention to you,” but said he “Intended to do it before I left town.” Instead, on his way home from Philadelphia, Darke wrote to the President, saying, “I wanted much to have seen you before I left the City but judging you were much ingaged in business of grate importance, did not wish to intrude. I wanted to know who would Command the army the insuing Campaign and I am informed Genl St. Clear has resigned…. Should you think me worthy of an appointment in the army I should want to know who I was to be Commanded by.”[38] Washington chose General Anthony Wayne, of Pennsylvania. Wayne was a controversial choice, especially in Virginia, and Darke was surprised. He said so to Lee, telling him that Washington had expressed a high opinion of him. He also noted that Knox had indicated Lee would not get the job. Lee took that to mean that Knox had undercut him, and complained to the President in a letter that Knox had “exerted himself to encrease certain difficultys which obstructed the execution of” Washington’s wishes.[39] Read together, the letters can be interpreted to indicate compounding misunderstandings and perhaps an overreaction on Lee’s part. Nevertheless, Washington was clearly annoyed with Darke. He told Lee that it was all nonsense and “declared” that “the conduct of Colo. D___ is uncandid, and that his letter is equivocal.” Wayne went on to achieve a major victory against the Indians at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. Darke was not asked to serve.[40] The Whiskey Rebellion He did, however, get a chance to serve under Henry Lee. While Wayne’s campaign was the largest military enterprise of 1794, it was not the only one. Darke and Washington were both more directly involved in another: the Whiskey Rebellion. A new federal excise tax on distilled spirits was seen as unfair by western farmers, who found whiskey far easier to transport and sell to eastern markets than raw grain or flour. When the Whiskey Rebellion grew out of control, Washington ordered a military operation to suppress it.

The entire Virginia force was under the command of the man Darke had recommended to Washington. Henry Lee was now the Governor of Virginia and decided to personally lead the Commonwealth’s forces. Lee estimated in a letter that the Pittsburgh tax protestors had about 16,000 men in arms, but predicted, “The division of sentiment among them will greatly diminish this force, and 8 or 9,000 will probably be the ultimate point they can reach. They abound in rifles, and are good woodsmen. Every consideration manifest the propriety of hurrying the march of the troops….”[42] Morgan ordered his men to rendezvous at Winchester on September 15. Darke and his men arrived on time, but “having neither arms, ammunition, or any kind of military stores” General Morgan thought it best to furlough them for a week. Finally, on October 6, another officer reported, “The State Arsenal has furnished us with 3,000 stand” of arms. “This supply enabled us to forward 2,000 men completely equipped on Saturday last. They marched under the command of General Dark. General Morgan follows to-day.”[43] President Washington personally led the advance of other troops from Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Darke and the southern troops rendezvoused with Washington at Cumberland, Maryland, and were reviewed there by the president. Washington then returned to Philadelphia, but left a letter commending the soldiers for their “patriotic zeal for the Constitution and Laws” of the nation. “No citizen of the United States can ever be engaged in a service more important to their country,” he wrote. “It is nothing less than to consolidate and preserve the blessings of that Revolution, which at much expense of Blood and Treasure constituted us a free and independent nation. It is to give to the world an illustrious example of the utmost consequence of the cause of mankind.”[44] Washington was very concerned about maintaining the moral high ground, seeking only to quell the uprising and enforce the tax law. He warned about acts of extrajudicial “justice” against the whiskey rebels. Daniel Morgan personally intervened to prevent such acts. Moreover, William Findley recalled that Morgan’s left wing (Darke’s men included) behaved better than the right wing of Pennsylvania and New Jersey troops. Findley wrote: In one or two instances, where there was danger of some foolish men who mixed with that wing being skewered, general Morgan, by pretending to reserve them for ignominious punishment, saved them, till they could be safely dismissed, or kept his men from killing them by threatening to kill them himself.[45] No accounts of General Darke’s conduct during the operation have been found, but the record shows that the men under Morgan restrained themselves. Findley noted that, “There was not so much of the inflammatory spirit observable in the left wing of the army as in the other, nor was there any persons killed by them, by accident or otherwise.”[46]  Darke, as a militia brigadier general, led Virginia troops in suppressing the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794. Darke, as a militia brigadier general, led Virginia troops in suppressing the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794. Before the army left, a separate corps was formed to encamp near Pittsburgh and “cause the laws to be duly executed.” It was a combination of men from the expedition force and of locals, some of whom “were said to have been the most troublesome of the insurgents.” It is not known if Darke was part of this force, which remained behind for another three months.[47] Nor is it known whether Darke and Washington spoke to each other at Cumberland when the President reviewed the troops there. Some contact seems almost certain given their relationship and Darke’s new rank as a general. Either way, it was probably the last time they encountered each other. The Indian war in the Northwest Territory was over and Washington was half way through his second and final term as President. Five years after the rebellion was put down the Father of the Country was dead. Two years after that, in 1801, Darke was dead as well. His last public office was an appointment to the court (government) of the newly-formed Jefferson County. The court met for the first time just two weeks before Darke died.[48] Conclusion On January 19, 1800, Henry Holcombe—a Revolutionary War officer turned Baptist preacher—delivered a prominent sermon on the life of Washington. He observed that Washington’s greatness was rooted in his freedom from pride and his trust in God. He said Washington’s “boldness and magnanimity, could be equaled by nothing but his modesty and humility.” Moreover, “he displayed an equanimity through the most trying extremes of fortune, which does the highest honor to the human character. He was the same whether struggling to keep the fragments of a naked army together in the dismal depths of winter, against a greatly superior foe, or presiding under the laurel wreath over four millions of free men!”[49]

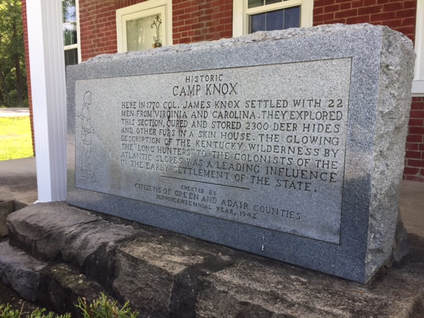

[1]Danske Dandridge, Historic Shepherdstown (Charlottesville: The Michie Company, 1910), 261. [2]Peter Force, ed., American Archives, (Washington: M. St. Clair Clark and Peter Force, 1837), 4th Ser., Vol. VI, p. 1556. [3]“From John Hurt,” January 1, 1792, The Papers of George Washington, W.W. Abbott, et al., eds. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1987-),Presidential Series, 9:358-366. [4]“Biographical Sketch of Gen. William Darke of Virginia by a Citizen of Frederick County, Maryland” in The Military and Naval Magazine of the United States, 6 (1835): 1-9; Dandridge, Historic Shepherdstown, 256; William Darke to George Washington, July 25, 1791, Jefferson County Museum manuscript collection, Charles Town, West Virginia; “Memoirs of Generals Lee, Gates, Stephen, and Darke,” HarpersNew Monthly Magazine,17 (1858): 509-510. [5]David Preston, Braddock’s Defeat (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 180-182, 338-340; René Chartrand, Monongahela 1754-1755: Washington’s Defeat, Braddock’s Disaster (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2004), 56-57; Samuel Kercheval, A History of the Valley of Virginia (Winchester: Samuel H. Davis, 1833, repr. Heritage Books, 2001), 67; Robert Rutherford affidavit, Berkeley County Land Bounty Certificate, 1780, cited in William Armstrong Crozier, Virginia County Records(Baltimore: Southern Book Company, 1904; reprinted as Virginia Colonial Militia: 1651-1776, Genealogical Publishing, 2000), 2:44; “From Robert Rutherford,” March 13 1792,” Papers of Washington, Presidential Series, 10:97-100. [6] “To Robert Rutherford,” June 24, 1758, Papers of Washington, Colonial Series, 5:239. [7]Kercheval, History of the Valley of Virginia, 86-87;Virgil A. Lewis, “General William Darke, A Distinguished West Virginia Pioneer,” reprinted in F. Vernon Aler, Aler’s History of Martinsburg and Berkeley County, West Virginia (Hagerstown, Md.: Mail Publishing, 1888), 193-199. [8]Robert K. Wright, Jr., The Continental Army (Washington: Center for Military History, 1986), 24-25; William Walter Hening, The Statutes At Large, Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia from the First Session of the Legislature in 1619 (Richmond: J. and G. Cochran, 1821) 9:16-25, 78, 80; Force, American Archives, Ser. 4, 6:1556; Guide to Military Organizations, 43. On June 8, the Virginia Convention heard a claim for expenses incurred by Darke and by Isaac Beall “for the expenses incurred in supporting their two Companies of Riflemen from the time of their being imbodied till the passing of the Ordinance directing the same to be raised.” Darke’s company was junior in seniority by John Stephenson’s company, which was transferred from independent service into the regiment. [9]Jonathan Clark, Diary,June 24, 1776, Filson Historical Society manuscript collection, Louisville, Ky.; Charles Lee to John Armstrong, July 14, 1776, in The Lee Papers,Henry Edward Bunbury, ed., 4 vols. (New York: New York Historical Society, 1871-1875), 2:139-140; William Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution, So Far as it Related to the States of North and South Carolina, and Georgia, 2 vols.(New York: David Longworth, 1802), 1:186; George M. Bedinger, The George Bedinger Papers: Volume 1A of the Draper Manuscript Collection, transc. Craig L. Heath (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 2002), 68; John Robert McNeill, Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620-1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 203,229. Lee had other regiments under his command, so the deaths of 14 or 15 men a day does not reflect mortality rates in the 8thVirginia alone. [10]Peter Muhlenberg to James Wood, September 29, 1801 and Peter Muhlenberg affidavit, December 10, 1802, both in Peter Helphinston file, Revolutionary Bounty Warrants, Library of Virginia; Journals of the Continental Congress, 7:52. Captain John Stephenson was senior to Darke, but his company’s term ended in the fall of 1776 and he left the regiment. [11]George Johnston to Peter Muhlenberg, March 9, 1777, Papers of Washington,Revolutionary War Series, 8:429. [12]“To Brigadier General William Woodford,” March 3, 1777, Papers of Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 8:507-508; JCC,7:351-352; John Fitzgerald to Richard Campbell, August 4, 1777, George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, Series 3b, Varick Transcripts, Letterbook 4:13; “To John Hancock,”May 16, 1777, Papers of Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 9:438-439; Washington, General Orders, September 29, 1777, Papers of Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 11:343; Compiled Services Records of American Soldiers Who Served in the Continental Army During the Revolutionary War, 1042:116, 118-119, 134, 146. [13]“Narrative of Sergeant William Grant,” in John Romeyn Brodhead, ed., Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York Procured in Holland, England, and France, (Albany: Weed, Parsons and Co., 1857), 8: 728-734; Clark, Diary,June 22-24; “To Major General Israel Putnam,”August 16, 1777, Papers of Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 10:642; McGuire, Philadelphia Campaign, 1:45-52. [14]“General Orders,” August 28, 1777, Papers of Washington,Revolutionary War Series, 11:81-82; “Narrative of William Grant,” 733. Grant describes how, in a skirmish, Darke “divided his men into 6 parties of 25 each.” [15]“From Major General Adam Stephen,” October 9, 1777, Papers of Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 11:468–470. [16]Elizabeth Paschal O’Connor (Mrs. T.P. O’Connor), My Beloved South(New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1913), 100-101; CSR, 1042:120, 121, 129, 133. [17]“Memorial of the Officers of the Virginia Line in Captivity,” May 24, 1780, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), 3: 388-391; “To Benjamin Harrison,” June 22?, 1780, Papers of Jefferson, 3:458; “To George Washington,” July 4, 1780, Papers of Jefferson,3:481; “To Governor Thomas Jefferson,” August 29, 1780, John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., The Writings of George Washington (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1937), 19:468. [18]“To George Washington,” October 25, 1780, Papers of Jefferson, 4:68; “To the Board of War,” November 4, 1780, Writings of Washington, 20:291-292. [19]Michael Cecere, The Invasion of Virginia 1781 (Yardley, Pa: Westholme, 2017), 8-10, 13-14, 22-23. [20]“To Daniel Morgan,” June 2, 1781, Papers of Jefferson, 6:70-71; William P. Palmer, ed., Calendar of Virginia State Papers (Richmond: Sherwin McRae, 1881), 2:162-163. [21]Don Higginbotham, Daniel Morgan: Revolutionary Rifleman (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1961), 161-166, citing Morgan to Nelson, June 26, 1781, Charles Roberts Autograph Collection, Haverford College Library. [22]Ebenezer Denny, Military Journal of Major Ebenezer Denny (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1859), 38-39; James Carter pension, 1833, C. Leon Harris, transc., revwarapps.com (viewed 12/17/17); Dandridge, Historic Shepherdstown,261. [23]James Carter pension, 1833; Dandridge,Historic Shepherdstown, 260-261 [24]Oliver Evans, The Young Mill-Wright and Miller’s Guide (Philadelphia: Oliver Evans, 1795), 500-507. [25]Sarah Peter, Private Memoir of Thomas Worthington, Esq. of Adena, Ross County, Ohio (Cincinatti: Robert Clarke & Co., 1882), 4, 9-10; Douglas R. Littlefield, “The Potomac Company: A Misadventure in Financing an Early American Internal Improvement Project,” The Business History Review, 58 (1984): 562-585. An Ohio-Potomac junction would certainly have required an overland portage as well, but the sources consulted don’t mention one. [26]Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, eds, The Diaries of George Washington (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia: 1979), 5:6,151-152; “From Henry Bedinger and William Good,” Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, 7:1. [27]Virginia Gazette and Weekly Advertiser, May 14, 1789. [28]Littlefield, “The Potomac Company,” 576, 583-584. [29]Hugh Blair Grigsby, The History of the Virginia Federal Convention of 1788 (Richmond: Virginia Historical Society, 1891), 2:363-366; Earl G. Swem and John W. Williams, A Register of the General Assembly of Virginia, 1776-1918 and of the Constitutional Conventions (Richmond: Davis Bottom, 1918), 34, 36, 243, 366. [30]Erik Goldstein, Stuart C. Mowbray, and Brian Hendelson, The Swords of George Washington (Woonsocket, RI: Mowbray Publishing, 2016), 63-68; Merrill Lindsay, “A Review of All the Known Surviving Swords of Gen. George Washington: How Many Swords Did George Washington Wear at His Inauguration?” American Society of Arms Collectors Bulletin, 32 (Fall, 1975), 37-49. [31]https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/19/Residence_Act_of_1790.jpg; Kenneth R. Bowling, The Creation of Washington D.C: The Idea and Location of the American Capital (Fairfax, VA: George Mason University Press, 1991), 123-125, 210-211. [32]Earl G. Swem and John W. Williams, A Register of the General Assembly of Virginia, 1776-1918 and of the Constitutional Conventions (Richmond: Davis Bottom, 1918), 34, 36, 243, 366; “To William Darke,” April 4, 1791, The Papers of George Washington,Presidential Series, 8:55-57. Darke’s appointment was made after two higher-profile officers declined the job. [33]John Winkler, Wabash 1791(Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2011),21, 29. [34]Wilson, “St. Clair’s Defeat,” 379; Winkler, Wabash,59-73; “Shiloh,” American Battlefield Protection Program, https://www.nps.gov/abpp/battles/tn003.htm(accessed 7/27/18). [35]Dandridge, Historic Shepherdstown,261; “From William Darke,”November9-10,1791,” Papers of Washington, Presidential Series, 9:158-168; Arthur St. Clair, Narrative of the Manner in Which the Campaign Against the Indians in the Year One Thousand Seven Hundren and Ninety-One, Was Conducted, Under the Command of Major General Arthur St. Clair (Philadelphia: Jane Aitken, 1812), 29; “Extract of a letter from Colonel ____, Commanding Officer of a Frontier County, to a Member of Congress—dated Lexington, January, 1792,” Dunlap’s American Daily Advertiser,February 10, 1792, cited in Papers of Washington, 10:156-157. [36]“Biographical Sketch,” Military and Naval Magazine,8; Wiley Sword, President Washington’s Indian War: The Struggle for the Old Northwest, 1790-1795 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press), 193; “From Robert Rutherford,” Papers of Washington, Presidential Series, 10:97-100. John Darke is not included on Ebenezer Denny’s list of officers wounded and killed in the battle. (Denny, Military Journal, 172-173.) Darke’s third son, Samuel, died four years later. [37]“From Robert Rutherford,” March 13, 1792, Papers of Washington, Presidential Series, 10:97; “To Henry Lee,” June 30, 1792, Papers of Washington, Presidential Series, 10:506-509. [38]“From William Darke,” circa April 25, 1792, Papers of Washington, Presidential Series, 10:314-315; “From Henry Lee,” June 15, 1792, Papers of Washington, Presidential Series, 10:455-457. [39]“To Henry Lee,” June 30, 1792, Papers of Washington, Presidential Series, 10:506-509. [40]“To Henry Lee,” June 30, 1792, Papers of Washington, Presidential Series, 10:506-509. [41] A Collection of All Such Acts of the Virginia General Assembly of Public and Permanent Nature as are Now in Force(Richmond: Samuel Pleasants, Jr. and Henry Pace, 1803), 282, 310; Brent Tarter,"William Darke (1736–1801)," Dictionary of Virginia Biography, Library of Virginia (1998– ), published 2015 (http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/bio.asp?b=Darke_William, accessed January 14, 2017); Don Higginbotham, Daniel Morgan: Revolutionary Rifleman (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1961), 184, citing “Morgan’s militia commission” in the Myers Collection, New York Public Library. The General Assembly transferred the power to appoint future militia generals to the governor on December 10, 1793. [42]“Henry Lee, Governor to General Wood, Lieutentant-Governor,” September 19, 1794, Calendar of Virginia State Papers, 7: 318. Henry Lee was the father of Robert E. Lee, who was born in 1807. [43]Daniel Morgan to the Governor, September 16, 1794, Calendar of Virginia State Papers, 7: 315-316, 341-342. [44]George Washington to Henry Lee, October 20, 1794, Calendar of Virginia State Papers, 7:356. [45]William Findley, History of the Insurrection in the Four Western Counties of Pennsylvania in the Year MDCCXCIV (Philadelphia: Samuel Harrison Smith: 1796), 148. See also Hugh H. Brackenridge, Incidents of the Insurrection in the Western Parts of Pennsylvania, in the Year 1794 (Philadelphia: John McCulloch, 1795), 61. [46]Findley, History of the Insurrection, 148. [47]Findley, History of the Insurrection, 321. [48]Tarter, “William Darke.” [49]Henry Holcombe, “A Sermon Occasioned by the Death of Lieutenant-General George Washington; first delivered in the Baptist Church, Savannah, Georgia, January 19, 1800, and now published, at the request of the Honorable City Council” (Savannah: Seymour and Woolhopter, 1800), (text posted at www.consource.org/document/a-sermon-occasioned-by-the-death-of-washington-by-henry-holcombe-1800-1-19/). Read More: Darkesville: A Name Born of Tragedy More from The 8th Virginia Regiment 8th Virginia Captain James Knox was one of the original "long hunters," the first white men to go deep into "Kentucky country" through Cumberland Gap. 8th Virginia Captain James Knox was one of the original "long hunters," the first white men to go deep into "Kentucky country" through Cumberland Gap. The adventures of 8th Virginia Captain James Knox have been unfairly overshadowed by those of Daniel Boone. This may be true generally, but it is definitely—and literally—true at the site of a memorial marker in Greene County, Kentucky. The 8th Virginia’s recruitment area was vast—covering almost the entire Virginia frontier, which at that time stretched from Pittsburgh to the Cumberland Gap—a distance of 450 miles. Those two places were, at that time, the only practical access points to the “Kentucky Country”—all of which was, at the start of the war, part of Fincastle County, Virginia. To get there, you could float down the Ohio River from Pittsburgh, or you could travel overland through the Cumberland Gap. Few had taken the latter route, however, when James Knox led a hunting party that way in 1770. Knox was one of the original “Long Hunters,” who entered Kentucky on months-long or even years-long hunting trips, intending to return with large quantities of pelts. Daniel Boone is by far the most famous of the long hunters, but that is partly because there is only room for one of these little-remembered adventurers in public memory. In 1770, James Knox and his team established a hunting camp and pelt repository (a “skin house”) by the north bank of a creek now known as Skinhouse Branch. Years later, a church was built on the same site. Today, the 187-year old nondenominational church sits at the intersection of Skinhouse Branch and Long Hunters Camp roads—neither of which carries enough traffic to warrant painted markings. It is surrounded by farms growing corn, tobacco, and soybeans. Two stone markers were put there long ago by local citizens to memorialize James Knox and the hunting expedition of 1770. In front of them, and closer to the road, is an official Kentucky state historic marker noting that Daniel Boone was also there—a year later. Early in 1776, Knox recruited one of the 8th Virginia’s ten companies. His men were decimated by malaria during the South Carolina expedition of that summer and fall. By the spring of 1777, only a handful were left. Knox became a captain in Morgan’s Rifles and commanded a company at the victory at Saratoga. He took a few of his 8th Virginia men with him, and his 8th Virginia Regiment company ceased to exist. He was a prominent citizen of Kentucky in his later years, but has always been overshadowed by Daniel Boone. Read More: "Searching for Captain Knox" (3/29/18)

About three months before July 4, 1776, the regiment’s ten companies began to rendezvous in Suffolk, Virginia. Tidewater Virginia was abuzz with military affairs and politics. Lord Dunmore, the colonial governor, had fled the capital. From the safety of a British naval vessel, he had promised freedom to slaves who fled their masters and took up arms for the king. He met with British General Henry Clinton who had come south with a sea-born army of redcoats. Where those redcoats were headed was unclear. Williamsburg expected an attack at any time. When Clinton sailed south, the 8th Virginia was ordered to follow him (on foot), to counter him where ever he might attack. They departed just as Virginia’s defiant revolutionary assembly voted in favor of Independence on May 15, empowering its delegation to propose it in Congress. Less than a month later, Thomas Jefferson produced a Declaration for all the colonies asserting it to be “self-evident” that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” The Declaration of Independence, in reference to Canada and Ohio, accused the King and Parliament of “abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies.” The subtext here was that the King was abandoning the principles of the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and reverting to the tyranny of the old Stuart monarchs. The French were not Virginia’s only enemies. Of special relevance for the 8th Virginia was Jefferson’s charge that the King had "endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.” Most of the army's senior officers were veterans of the French and Indian War. Braddock’s defeat in 1755 had unleashed an era of conflict with the Indians in the Ohio Valley that would not really end until the War of 1812. There was already strong evidence that the King’s agents were stirring up the Cherokee and the Shawnee to create a two-front war for the Americans.

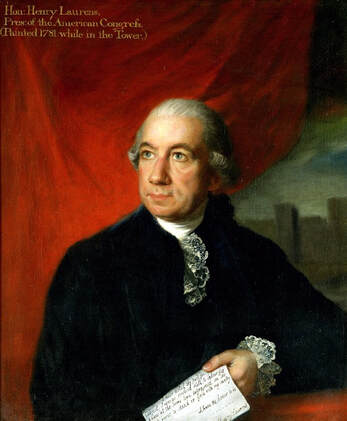

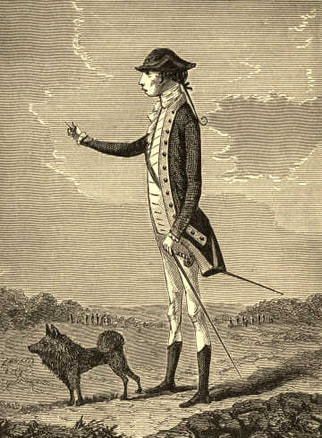

There was, according to Henry Laurens, a “Procession of President, Councils, Generals, Members of Assembly Officers & Military &c &c amidst loud acclamation of thousands.” The troops were assembled along with civilians. The tree was located north of town in an open area that would not be built on until after the war. “Thither the procession moved from the city…embracing all the young and old, of both sexes, who could be moved so far. Aided by bands of music, and uniting all the military of the country and city, in and near Charleston, the ceremony was the most splendid and solemn that ever had been witnessed in South Carolina.” No one seems to have noted the irony that the main speaker at the event was shaded and fanned by a slave as he expounded on liberty and freedom. It would take a long time for the full implication of the Declaration’s assertion that “all men are created equal” to penetrate American minds. For South Carolina and for Muhlenberg’s men, this was the high point of the war. The Battle of Sullivan’s Island was a tremendous victory that defied all odds and expert predictions. By the start of August, Americans had inflicted heavy blows upon the British regulars at Lexington and Concord, Ticonderoga, Bunker Hill, Great Bridge, Norfolk, Moore’s Creek Bridge, the siege of Boston, and now also at Charleston. The only major loss had been in Canada. The war was going well. America was winning and America had declared its independence. As summer turned into fall, however, fortunes changed. Washington suffered a series of major defeats in New York and New Jersey. The 8th Virginia marched on toward Florida on a mission they could not complete. The regiment’s mountain boys were already succumbing to the low country’s heat and ubiquitous mosquitos. For weeks, those mosquitos had been silently spreading malaria among the men. Those who had the weakest resistance, the ones born and raised in the Virginia mountains, began to die.  The Battle of Fort Moultrie, painted by John Blake White in 1826. Maj. Gen. Charles Lee is portrayed in the foreground with his arm outstretched toward Col. William Moultrie, who is holding a sword. The 8th Virginia did not participate in the defense of the fort, which was called Fort Sullivan until after the battle. (United States Senate) Learn more: Nic Butler, "Declaring Independence in 1776 Charleston" More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

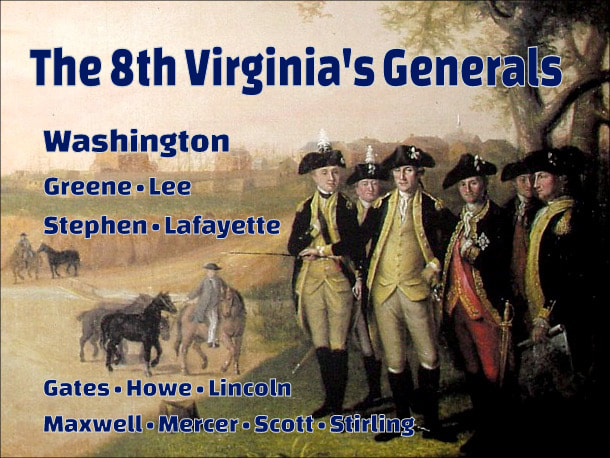

In 1777, the main body of the regiment served in Maj. Gen. Adam Stephen's division at Brandywine and Germantown. A small group of riflemen from the 8th were detached to Daniel Morgan’s Rifle Battalion under the command of Captain James Knox and participated in the Saratoga campaign. A few dozen were detached for a month to William Maxwell's Light Infantry in August and September of 1777 under the command of Captain (later and retroactively Major) William Darke, at Cooch's Bridge and Brandywine. Stephen was replaced by the Marquis de Lafayette late in the year. In 1778, with its ranks severely depleted by disease, casualties, and expired enlistments, the 8th was folded into the 4th Virginia after the Battle of Monmouth. 1776 Southern Campaign (Sullivan’s Island, Savannah, Sunbury): Gen. George Washington, Commander in Chief (not present) Maj. Gen. Charles Lee, Commander of the Southern District Brig. Gen. Andrew Lewis (Tidewater service) Brig. Gen. Robert Howe (Cape Fear, Charleston, Savannah, Sunbury) Captain Croghan Detachment attached to 1st Virginia (White Plains, Trenton, Assunpink Creek, Princeton): Maj. Gen. Joseph Spencer (White Plains) Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene (Trenton and Princeton) Col. George Weedon (temporary brigade at Fort Washington) Brig. Gen. William Alexander, Earl of Stirling (White Plains through Trenton) Brig. Gen. Hugh Mercer (Princeton) 1777 Philadelphia Campaign (Brandywine, Germantown, Valley Forge) Gen. George Washington, Commander in Chief Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln (New Jersey rendezvous) Maj. Gen. Adam Stephen (Brandywine, Germantown) Maj. Gen. Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette (Valley Forge) Brig. Gen. Charles Scott Captain Knox Detachment under Colonel Daniel Morgan (Saratoga) Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln Captain Darke Detachment in Maxwell's Light Infantry (Cooch's Bridge, Brandywine) Brig. Gen. William Maxwell 1778 Campaign (Valley Forge, Monmouth): Gen. George Washington, Commander in Chief Maj. Gen. Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette Maj. Gen. Charles Lee (at Monmouth) Brig. Gen. Charles Scott Col. William Grayson (temporary brigade commander at Monmouth) More from The 8th Virginia Regiment Mosquitos were an unrecognized but deadly enemy in the Revolutionary War, and no troops suffered more from them than the 8th Virginia. The current plague of mosquitos in South Carolina is a reminder of what Colonel Peter Muhlenberg and his men had do deal with in the summer and fall of 1776. After record October rainfalls, South Carolina is presently experiencing record numbers of mosquitos, and citizens are calling for state or even federal action to combat the bugs. Tony Melton of Florence, S.C., told a reporter this week that mosquitos were “eating me alive” the last time he tried to ride his tractor through his sweet potato field. “People are stayng inside; that’s the bottom line.” Mosquitos are nothing new to South Carolina. In 1774 a resident called them “devils in miniature.” In May of 1776, The 8th Virginia Regiment rushed south from Virginia to help defend Charleston, South Carolina. On their arrival, Captain Jonathan Clark spent much of the first week staying at the home of Christopher Gadsden. He initially camped in Gadsden’s garden, but recorded that upon the “arr[ival] of [the] Moschetto” he got up and moved “in the House.” Enlisted men didn't have the option. The Battle of Sullivan’s Island on June 28 was a major early victory for the Americans, and the successful defense by South Carolina provincial troops of the Island’s half-finished fort was regarded as a virtual miracle. About three companies of the 8th Virginia (Continental troops) were posted at the opposite end of the island blocking a cross-channel infantry attack. Major General Lee praised his Continentals after the battle. “I know not which Corps I have the greatest reason to be pleased with Muhlenberg’s Virginians, or the North Carolina troops—they are both equally alert, zealous, and spirited.” Though they fended off the British, many of them lost their battle with the mosquitos. Unlike the mosquitos bothering Tony Melton, the mosquitos of 1776 carried malaria. By August, 150 8th Virginia men were sick. By fall, a few were dying every day. Muhlenberg got it and would never fully recover. Major Peter Helphinstine got it and was so sick he was forced to resign his commission and died a slow death at home in Virginia. As measured by death and illness, malaria was the 8th Virginia's number one enemy in the war--and nobody knew what caused it. Most people thought it was bad air ("mal aria") hovering over swamps and other areas. In fact, it was the mosquitos that breaded in such places.Today, malaria has been eradicated in South Carolina, Georgia and other warm, wet areas of the United States. It continues to kill millions every year in Africa and other developing parts of the world. |

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed