- Published on

The Fourth of July in Soldiers’ Eyes

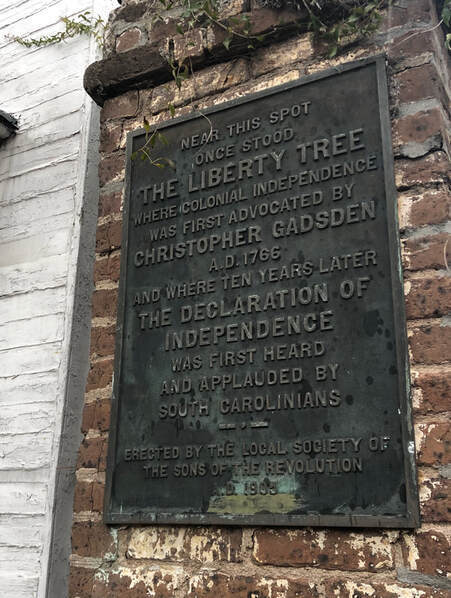

The 8th Virginia celebrated the Declaration of Independence under the Liberty Tree outside Charleston, South Carolina. (Author)

The men of the 8th Virginia learned of the Declaration of Independence on the heels of a major victory. For nearly all of them, it was the high point of the war. It was followed by very deep lows.

Two hundred and forty years later, most of us celebrate America’s independence with cookouts and fireworks. Colonel Peter Muhlenberg’s soldiers experienced the event in its original context, which meant learning of it many days after the fact. News traveled slowly back then. When they heard it read, a month after it was signed, the list of grievances in the middle of the document probably meant more to them than the high-minded introduction we focus on today. As is true in every era, their personal aspirations and disappointments meant more to most people than abstract ideas of political philosophy.

Two hundred and forty years later, most of us celebrate America’s independence with cookouts and fireworks. Colonel Peter Muhlenberg’s soldiers experienced the event in its original context, which meant learning of it many days after the fact. News traveled slowly back then. When they heard it read, a month after it was signed, the list of grievances in the middle of the document probably meant more to them than the high-minded introduction we focus on today. As is true in every era, their personal aspirations and disappointments meant more to most people than abstract ideas of political philosophy.

About three months before July 4, 1776, the regiment’s ten companies began to rendezvous in Suffolk, Virginia. Tidewater Virginia was abuzz with military affairs and politics. Lord Dunmore, the colonial governor, had fled the capital. From the safety of a British naval vessel, he had promised freedom to slaves who fled their masters and took up arms for the king. He met with British General Henry Clinton who had come south with a sea-born army of redcoats. Where those redcoats were headed was unclear. Williamsburg expected an attack at any time.

When Clinton sailed south, the 8th Virginia was ordered to follow him (on foot), to counter him where ever he might attack. They departed just as Virginia’s defiant revolutionary assembly voted in favor of Independence on May 15, empowering its delegation to propose it in Congress. Less than a month later, Thomas Jefferson produced a Declaration for all the colonies asserting it to be “self-evident” that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

When Clinton sailed south, the 8th Virginia was ordered to follow him (on foot), to counter him where ever he might attack. They departed just as Virginia’s defiant revolutionary assembly voted in favor of Independence on May 15, empowering its delegation to propose it in Congress. Less than a month later, Thomas Jefferson produced a Declaration for all the colonies asserting it to be “self-evident” that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Jefferson’s document also contained a long list of indictments against the King, including some that were of particular importance to the men of the 8th Virginia. At the end of the French and Indian War, the victorious British King had allowed the Canadians to maintain their French laws. He had extended the Province of Quebec south to the banks of the Ohio River, while also prohibiting new English settlements west of the Alleghenies. This obstructed the dreams of Virginia’s frontiersmen—and offended the convictions of those who hated (and had fought against) the French. The French, and their Catholic faith, were hated by the English who saw them as champions of tyranny. The parents of many 8th Virginia men had fled French armies in Germany.

The Declaration of Independence, in reference to Canada and Ohio, accused the King and Parliament of “abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies.” The subtext here was that the King was abandoning the principles of the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and reverting to the tyranny of the old Stuart monarchs.

The French were not Virginia’s only enemies. Of special relevance for the 8th Virginia was Jefferson’s charge that the King had "endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.” Most of the army's senior officers were veterans of the French and Indian War. Braddock’s defeat in 1755 had unleashed an era of conflict with the Indians in the Ohio Valley that would not really end until the War of 1812. There was already strong evidence that the King’s agents were stirring up the Cherokee and the Shawnee to create a two-front war for the Americans.

Charleston celebrated the Declaration under a southern live oak tree that had served as the city's "liberty tree" since the Stamp Act crisis. The tree was cut down by the British in 1780.

The 8th Virginia was in South Carolina when the Declaration was signed. (Many of them, under the command of Major Peter Helphenstine, had participated in the miraculous victory on Sullivan’s Island on June 28.)

News of the Declaration arrived in Charleston on either July 31 or August 2. A celebration was immediately planned. On an “intensely hot” day, August 5, all of Charleston was assembled and paraded out of the city to South Carolina’s Liberty Tree for the first formal reading of the document.

News of the Declaration arrived in Charleston on either July 31 or August 2. A celebration was immediately planned. On an “intensely hot” day, August 5, all of Charleston was assembled and paraded out of the city to South Carolina’s Liberty Tree for the first formal reading of the document.

There was, according to Henry Laurens, a “Procession of President, Councils, Generals, Members of Assembly Officers & Military &c &c amidst loud acclamation of thousands.” The troops were assembled along with civilians. The tree was located north of town in an open area that would not be built on until after the war. “Thither the procession moved from the city…embracing all the young and old, of both sexes, who could be moved so far. Aided by bands of music, and uniting all the military of the country and city, in and near Charleston, the ceremony was the most splendid and solemn that ever had been witnessed in South Carolina.” No one seems to have noted the irony that the main speaker at the event was shaded and fanned by a slave as he expounded on liberty and freedom. It would take a long time for the full implication of the Declaration’s assertion that “all men are created equal” to penetrate American minds.

For South Carolina and for Muhlenberg’s men, this was the high point of the war. The Battle of Sullivan’s Island was a tremendous victory that defied all odds and expert predictions. By the start of August, Americans had inflicted heavy blows upon the British regulars at Lexington and Concord, Ticonderoga, Bunker Hill, Great Bridge, Norfolk, Moore’s Creek Bridge, the siege of Boston, and now also at Charleston. The only major loss had been in Canada. The war was going well. America was winning and America had declared its independence.

For South Carolina and for Muhlenberg’s men, this was the high point of the war. The Battle of Sullivan’s Island was a tremendous victory that defied all odds and expert predictions. By the start of August, Americans had inflicted heavy blows upon the British regulars at Lexington and Concord, Ticonderoga, Bunker Hill, Great Bridge, Norfolk, Moore’s Creek Bridge, the siege of Boston, and now also at Charleston. The only major loss had been in Canada. The war was going well. America was winning and America had declared its independence.

As summer turned into fall, however, fortunes changed. Washington suffered a series of major defeats in New York and New Jersey. The 8th Virginia marched on toward Florida on a mission they could not complete. The regiment’s mountain boys were already succumbing to the low country’s heat and ubiquitous mosquitos. For weeks, those mosquitos had been silently spreading malaria among the men. Those who had the weakest resistance, the ones born and raised in the Virginia mountains, began to die.

The Battle of Fort Moultrie, painted by John Blake White in 1826. Maj. Gen. Charles Lee is portrayed in the foreground with his arm outstretched toward Col. William Moultrie, who is holding a sword. The 8th Virginia did not participate in the defense of the fort, which was called Fort Sullivan until after the battle. (United States Senate)

Learn more: Nic Butler, "Declaring Independence in 1776 Charleston"

Can't help but wonder if my 3rd great grandfather Peter Kern with the 8th VA wasn't there to celebrate and witness the Declaration of Independence.

Thanks. Gerald Karnes

I have a watercolor painting of the Courthouse at Williamsburg, VA where the News was read and shared also. Hard to believe how news traveled then compared to our 'breaking news' now.