Though still insufficiently covered in classrooms, the Battle of Kings Mountain is recognized as the key event in the demonstration of popular southern refusal to submit to Loyalist rule. Even less well-remembered is the smaller Battle of Musgrove’s Mill, without which there may have been no Kings Mountain. It was a little encounter in which just 200 Patriot militiamen faced off against 264 Loyalist regulars and militia. Though small, it sent a strong signal that backcountry Americans simply would not be ruled any longer by a foreign king. Giving such small battles their due is the purpose of Westholme Publishing’s “Small Battles” series. The Battle of Musgrove’s Mill, 1780 comes from the pen of John Buchanan, the undisputed dean of southern Revolutionary War history. Now in his 90s, Buchanan writes as well as ever. In fewer than a hundred pages, he puts the story in context; explains the British, Tory, Indian, and Patriot perspectives; tells us about the key commanders on both sides; narrates the battle; and tells us why it matters. That is a lot to put into eighty-eight pages of text, but he has done it masterfully. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

1 Comment

Professor Muñoz argues persuasively, however, that scholars, lawyers, and judges have all done a consistently sloppy job of seeking to understand what the founders actually meant by the words they used. So much so, in fact, that the original meaning of the Establishment and Free Expression clauses has effectively been lost. The result is that the text has become an ideological Rorschach test. It can be made to mean almost anything. “The consensus that the Founders’ understanding should serve as a guide has produced neither agreement nor coherence in church-state jurisprudence,” Dr. Muñoz writes. “Indeed, it has produced the opposite; it seems that almost any and every church-state judicial position can invoke the Founders’ support. Many readers will be surprised to hear that the Founders themselves are largely to blame for this. The language of the First Amendment itself (“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof”) is not very precise. The reason for this is that “Many, if not most, of the individuals who drafted the First Amendment did not think it was necessary.”[2] Establishment was a state issue and the Federal constitution already banned religious tests in Article VI.[3] It was the Anti-Federalists who insisted on the Bill of Rights, but they were in the minority in the 1st Congress. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

He described the priest’s ornate vestments, the beautiful music, and the bloody crucifix above the altar. “Here is every Thing which can lay hold of the Eye, Ear, and Imagination. Every Thing which can charm and bewitch the simple and ignorant. I wonder how Luther ever broke the spell.” He admitted, though, that the sermon was good. Protestants’ views of Catholics aside, it was the Church itself, and more specifically the Papacy, that presented a problem for the British Empire. The influential political thinker John Locke asserted in his 1689 Letter Concerning Toleration that a “church can have no right to be tolerated by the magistrate, which is constituted upon such a bottom, that all those who enter into it . . . deliver themselves up to the protection and service of another prince.”[3] By tolerating such a church, a ruler would “suffer his own people, to be lifted, as it were, for soldiers against his own government.”[4] The example he used was Islam, but it was Catholicism he was concerned about. Michael Breidenbach is a Cambridge University-educated associate history professor at Ave Maria University, an orthodox Catholic school in Florida. His book Our Dear-Bought Liberty: Catholics and Religious Toleration in Early America illustrates the remarkably rapid transformation of Americans’ treatment of Catholics during the Founding Era. Irish Catholics like Capt. John Barry, Lt. Col. John Fitzgerald, and Col. Stephen Moylan played important roles in the Continental Navy and Army. Maryland’s Charles Carroll signed the Declaration of Independence and held a seat on the Continental Congress’s powerful Board of War. Generals Lafayette and Pulaski were both Catholic, as were the French and Spanish empires that came to America’s aid. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

Fundamental to Carté’s analysis is understanding that the Church of England was just one of three denominations that represented a compound Imperial religious establishment. Anglicans, Presbyterians, and Congregationalists all held privileged status in different parts of the Empire: Anglicans in England and the American South, Presbyterians in Scotland, and Congregationalists in New England. Carté describes a tripartite “scaffold” of establishment that bound Protestants together and united the King’s dominions. Protestantism defined the British Empire more than Englishness did, since most of its subjects were not English. ...continue to the Journal of the American Revolution. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

Lord de la Warr’s name appears frequently in Mr. Sterner’s story. His name was given to the Delaware River, which in turn lent its name to the Lenape people who have long been known to English speakers as the Delaware Tribe. Mr. Sterner has provided the definitive account of the worst atrocity of the Revolutionary War. In 1782 more than eighty white settlers clubbed, killed, and scalped ninety-six peaceful, Christian Indians as they prayed and sang hymns. The attack on the Moravian mission town of Gnadenhutten (Ohio) was intended as both a punitive and preemptive strike, conducted by settlers whose families and farms had been targeted by other Indians acting as proxies of the British. It is a horrific story that has defied understanding until now. ...continue to Emerging Revolutionary War Era. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment “In a place like Salisbury,” writes Andrew Waters of the North Carolina town that witnessed the 1781 Race to the Dan, “you can live among its ghosts and still not know it’s there.” Enthusiasts know that this is true of many Revolutionary War sites, including some of real importance. Mr. Waters complains in his book To the End of the World: Nathanael Greene, Charles Cornwallis, and the Race to the Dan of the simplified understanding most Americans have of the Revolutionary War. “For most of us, the story of the American Revolution is of George Washington and the minutemen, Valley Forge and Yorktown.” In our Cliffs Notes version of history, many places, heroes, and even whole campaigns are left out. Like most of the war in the south, the Race to the Dan is overshadowed by Yorktown. The mere fact that George Washington was not a participant relegates the story to a second-tier status. The Race, however, holds unique challenges for the historian and the storyteller. It occurred over more than two hundred miles, depending on how you count it, rather than at one identifiable spot. Nathanael Greene’s genius is to be found in his mastery of logistics and strategy, which are subjects that make many people’s eyes glaze over. Though heroic and difficult, it was still a retreat and retreats don’t lend themselves to celebration. Its significance is not so much in what it achieved but rather in what it made possible, which requires detailed explanation. Consequently, the Race to the Dan has been given short shrift for more than two centuries. It is mentioned in the war’s histories, but almost never in detail. In writing this book, Mr. Waters was determined to correct that and he has succeeded. One can’t resist noting the appropriateness his name: the waterways of the Carolinas play a central role in the story. He makes plain from the beginning that the story is personal to him. He is a conservationist and doctoral candidate in South Carolina who has made a career of conserving the Palmetto State’s watersheds. “Rivers are my business,” he says at the very beginning of the book. He also plainly declares, “We all need heroes, and . . . Greene has become one of mine.” ...Continue to The Journal of the American Revolution. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

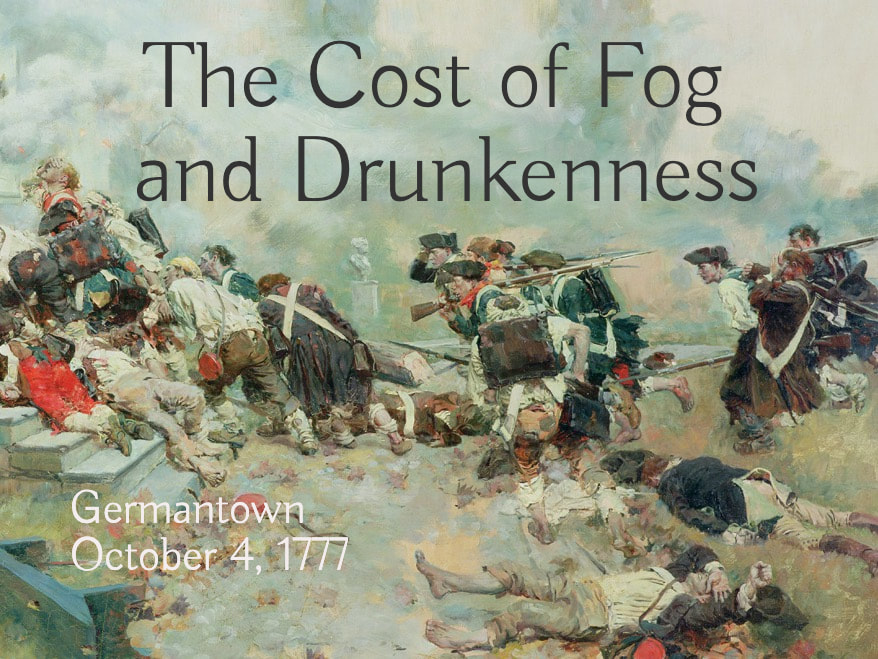

Several histories have appeared in this century that have broken significant new ground in this regard. In The 10 Key Campaigns of the American Revolution, Lengel pulls together a Dream Team of these writers to provide a fresh, top-level overview of the war. Each of the ten authors takes a chapter, providing an authoritative and readable account of a campaign. For those already steeped in the subject matter, the book offers an opportunity to step back from the trees and look again at the forest. For those who are new to the military history of the founding era, it is an excellent primer. Best of all, it is a book filled with good stories. Who doesn’t love the drama of the Ten Crucial Days and King’s Mountain? Admittedly, there is something odd about writers who know so much about their subjects writing so briefly on them. How on Earth, one must ask, did Michael Harris manage to tell the story of Brandywine and Germantown in a mere eighteen pages? Yet, each of them does it quite well: providing very readable narratives that feature new or recent insights and well-colored characters. Some of the contributors ask and answer difficult questions. Washington and Lafayette, two of the war’s great heroes, are brought down a peg. History has been kinder to Benedict Arnold for some time. Now Charles Lee and Philip Schuyler are also given more sympathetic treatments. Continue to ...The Journal of the American Revolution More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

He is best-known as the rector of a Shenandoah Valley (Anglican) parish and colonel of the 8th Virginia Regiment, which was raised on the frontier and initially intended to be a “German” regiment. The famous but poorly-documented farewell sermon he delivered in Woodstock, Virginia, in the spring of 1776 has been the subject of epic poetry and modern political debate. After a tour of the southern theater under Maj. Gen. Charles Lee, he was made a brigadier general. His brigade of Virginians was in Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene’s division at Brandywine and Germantown. He was at Monmouth and remained in the army to the end of the war. He played an important role in the Virginia campaign leading up to Yorktown. ...continue to The Journal of the American Revolution. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

William Croghan has never been famous, but his life illustrates the aspirations and achievements of America’s early frontiersmen. He fought for national expansion and then played an important role in that expansion by moving to Kentucky and running the office that parceled out bounty land to veterans. This was a lucrative position. Croghan prospered and built a stately home, which he called Locust Grove. ...continue to The Journal of the American Revolution. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment |

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed