Darke fought in the French & Indian War as a young man and may have been at Braddock’s defeat in 1755. He raised one of the first companies for the 8th Virginia in 1776 and was promoted from captain to major in 1777 shortly before his capture at Germantown. That was followed by three years in British captivity. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel while in enemy hands. He was exchanged late in 1780 and returned home just before Lord Cornwallis invaded Virginia. Darke helped General Daniel Morgan recruit a force of 18-month Continentals in the lower Shenandoah Valley and was present for the victory at Yorktown.

Those who survived, however, made it out alive because Lt. Colonel Darke led one last desperate charge through the Indian line, opening a hole through which the panicking soldiers could flee. Darke himself was wounded in the leg. His son, Captain Joseph Darke, was shot in the head and would die after a month of “unparalleled suffering.” Colonel Darke returned home just in time to witness the death of another of his three sons. (Darke’s last surviving son died five years later, leaving the hero with no one to carry on his name—something that bothered him greatly.)

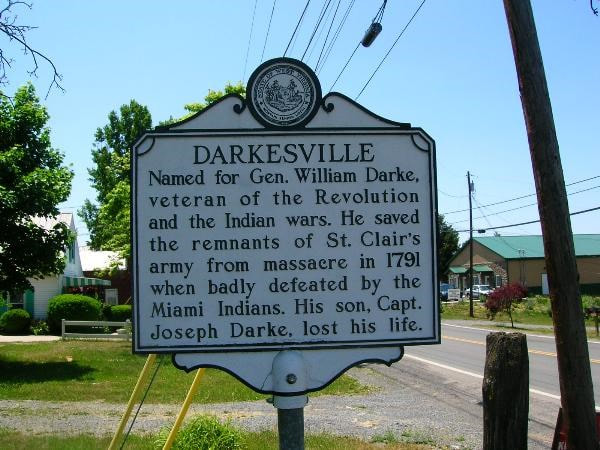

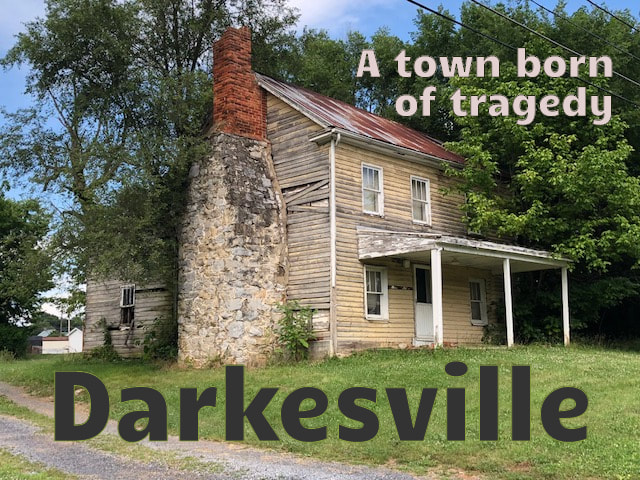

I recently stopped in Darkesville (now in West Virginia) to look around. For the casual observer, there is little to distinguish the village from more modern development along the road (Route 11). The state historic marker appears to be missing and I wasn’t able to find General Darke’s Headquarters, though I was later able to find its apparent location on a map.

41 Comments

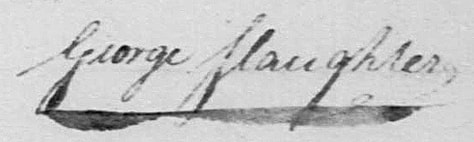

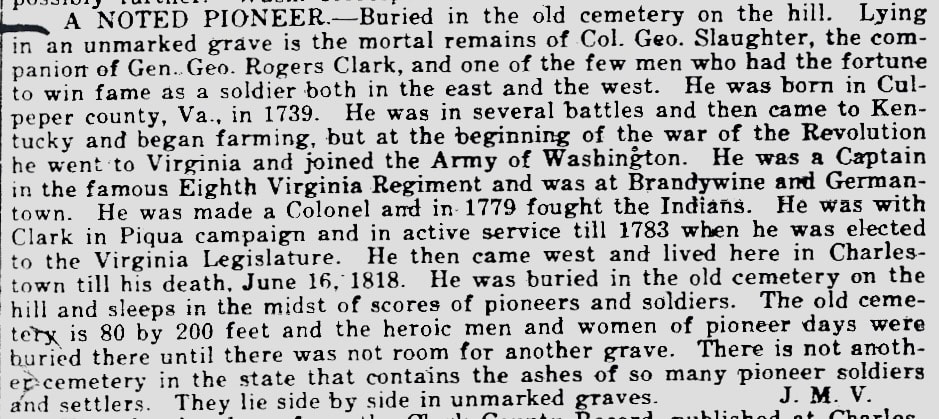

An 8th Virginia soldier like Captain George Slaughter might have seen the Revolution as just one chapter in a six-decade fight with the Indians for control of Kentucky and Ohio. The territories were the scenes of nearly constant bloodshed from the defeat of General Edward Braddock in 1755 to the defeat of Shawnee chief Tecumseh in 1813. After more than two decades of intermittent barbarity, Slaughter and his comrades suffered from no moral anguish when it came to killing Indians.

A decade later, he participated in Dunmore’s War. This was another campaign, led by the royal governor of Virginia, to “pacify” the Indians. After a lengthy and bloody battle at Point Pleasant on the Ohio River, the Virginians were victorious. Slaughter’s unit, however, reportedly arrived too late to participate in the fighting. "They had not the satisfaction of carrying off any of our men's scalps, save one or two of the stragglers," he wrote to his brother. "Many of their dead they scalped, rather than we should have them; but our troops scalped upwards of twenty of their men, that were killed first." His father-in-law was killed in the battle. After the campaign ended, Slaughter explored Kentucky for a while and planted corn—perhaps to lay claim to some land. A year later, in 1775, he may have helped recruit one of the first companies for the famous Culpeper Minutemen. The minute battalions were replaced in 1776 by additional full-time regular regiments, including the 8th Virginia. Slaughter recruited a company in Culpeper County. He remained with the regiment through Charleston and Brandywine and was then promoted to major of the 12th Virginia just before the Battle of Germantown. At Valley Forge, in December of 1777, he learned that his family had lost their house in a fire. That, and a smallpox epidemic (against which he, but not his family, had been inoculated), prompted him to request a furlough from General Washington. The furlough was turned down. He resigned his commission on December 23 and headed home to Culpeper. On February 1, he contritely wrote to Washington begging to be reinstated. “If my reenstation can take place with propriety,” he wrote, “it will afford me great satisfaction; if not, I hope I can Acquiesce without murmuring.” The request was denied. Virginia authorized four battalions of six-month volunteers in June 1778. These were state (not Continental) soldiers intended to reinforce Washington's army. Slaughter was chosen to lead one of the battalions. However, in August Congress advised the Commonwealth that the battalions would not be needed and the half-recruited units were disbanded. It is possible, however, that Slaughter's battalion was ultimately repurposed rather than dissolved. After George Rogers Clark’s important victories in the west, Maj. John Montgomery returned to Virginia with dispatches. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel and ordered to recruit additional forces to reinforce Clark. On January 1, 1779, Gov. Patrick Henry drafted orders for Clark based on decisions of the state legislature. “They have directed your battalion to be completed, 100 men to be stationed at the falls of the Ohio under Major Slaughter, and one only of the additional battalions to be completed. Major Slaughter’s men are raised, and will march in a few days, this letter being to go by him. The returns which have been made to me do not enable me to say whether men enough are raised to make up the additional battalion, but I suppose there must be nearly enough. This battalion will march as early in the spring as the weather will admit.”

Slaughter’s participation in Shelby’s campaign is circumstantially supported by the fact that he was once again recruiting in Virginia in the fall of 1779. Slaughter recruited 150 men who were sworn into the service in mid-December when they headed west. They made it as far as Redstone Fort in Pennsylvania before getting bogged down by snow. In the spring, they made it to Fort Pitt and boated downstream to the falls of the Ohio River. This site is now Louisville, Kentucky, a city of which Slaughter is considered a founder—he was one of the original trustees.

Safety was not his only problem. He also reported, “We are here without money, Clothing, or any thing else scarsely to subsist on. By the fault of the Commissaries, Hunters or I cannot tell who upwards of One hundred and Thirty Th[ousan]d weight of meat was intirely spoiled and lost.” Things improved for Slaughter and his neighbors from there. This can be seen in a letter his old 8th Virginia commander Colonel Abraham Bowman (who moved to Kentucky in 1779) sent home on October 10, 1784. Bowman wrote to a brother that "General Clark has laid off a town on the other side of the Ohio, opposite the falls, at the mouth of Silver creek, and is building a saw and grist mill there." This was Clarksville, in Clark County, Indiana. The same year, Slaughter was elected to the Virginia legislature. In 1792 Kentucky became its own state.

(Revised and updated, December 22, 2019 and June 15, 2022.) More from The 8th Virginia Regiment |

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed