The Marquis de Lafayette with the 8th Virginia. (Frank Schoonover) The Marquis de Lafayette with the 8th Virginia. (Frank Schoonover) The 8th Virginia was composed of ten companies. Each one was supposed to have 68 enlisted men led by four officers (captain, 1st lieutenant, 2nd lieutenant, and ensign). At least one overenlisted and one underenlisted. The overall regiment was commanded by three field officers (colonel, lieutenant colonel, and major) assisted by several staff officers (chaplain, adjutant, surgeon, surgeon's mate, paymaster, and quartermaster). One inherited company was composed men on 1-year enlistments that began in December of 1775. The other nine companies served 2-year enlistments, beginning in the spring of 1776 and ending at Valley Forge in the spring of 1778. An 11th company was raised to replace the 1-year men in 1777. Replacements recruited in 1777 served 3-year enlistments. The 8th existed from December 13, 1775 when it was authorized by the Virginia Convention, to September 14, 1778 when it merged with the 4th Virginia and took that number. I have posted an outline of the regiment's structure, listing officers and some enlisted men (when I have written about them or heard from descendants). This is not intended to be a full "roster" of the regiment, but rather a look at its structure, origins, and organization. The names of known descendants are in brackets after a soldier's name. An alphabetical lift of descendants is available on The Family Page. If you would like to be identified with your ancestor, please send an email over the web form. Your email address will be linked from your name only if you specifically request it.

14 Comments

A historic marker in Pendleton County, West Virginia tells the story of fifteen year-old William Eagle, who enlisted in the 8th Virginia on Christmas Eve, 1776. This was the Revolution's darkest hour. Washington's dwindling army had fled from the British across New Jersey and was now huddling, frozen by fear and cold on the West Bank of the Delaware. At a moment when few were willing to enlist, this teenage patriot stepped forward. Except it isn't true. Eagle's pension gives the same date that appears on the sign, but they are both wrong. The sign probably takes its date from the pension. As far as we know, Eagle served honorably and well. But he didn't enlist until December of 1777 when he was sixteen years old. The evidence is clear. First, His name appears nowhere in the muster or pay rolls for 1777, and the "commencement of pay" date on his first pay roll entry is February 1, 1778. Second, His pension affidavit claims that he "enlisted for the term of three years, on or about the 24th day of December in the year 1776, in the state of Virginia in the Company commanded by Captain Stead or Sted or Steed, in the Regiment commanded by Colonel Nevil or Neville." Colonel John Neville (no known relation to me) commanded the regiment after it was folded into the 4th Virginia in the fall of 1778. Had Eagle enlisted in the regiment in December of 1776 and joined it in January of 1777 he would certainly have mentioned Colonel Abraham Bowman, who became a "supernumerary" officer and was released from service when the regiments merged. Eagle served under Bowman only for a short while and, consequently, did not mention him. Eagle got the names right (Neville and Steed), but the year wrong. Third, the term of his enlistment is consistently recorded as for 3 years or the length of the war (which ever was shorter). Soldiers who enlisted in 1777 or later enlisted under these terms. Virginia soldiers who enlisted in 1776 signed up for two years. (Someone might argue that a date so late in the year might have been treated differently, but I'm not aware of any examples of this.) The date of his enlistment is not recorded anywhere in the surviving official records. From the evidence, however, it seems certain that he in fact enlisted "on or about the 24th day of December" in the year of 1777--not 1776--and joined the regiment at Valley Forge about a month later. Eagle is not the only veteran who got the dates of his service wrong when applying for a pension decades later. It is an understandable error for an old man to make. The State of West Virginia might, however, want to invest in an updated marker. So what happened to William Eagle? After nearly two years of service he was “discharged for inability” on September 1, 1779. Tradition has it that he had a broken arm. Whatever his injury was, it saved him capture following the surrender of the Virginia Line after the Siege of Charleston in May of 1780. William Eagle’s grave is by Eagle Rocks, a steep peak near the headwaters of the Potomac in West Virginia’s remote Smoke Hole Canyon. Ross B. Johnston wrote in his book West Virginians in the Revolution that the veteran named his son George Washington Eagle, and he nearly lost his life one day climbing his namesake peak in an attempt to capture some baby eagles. (Revised December 21, 2019)

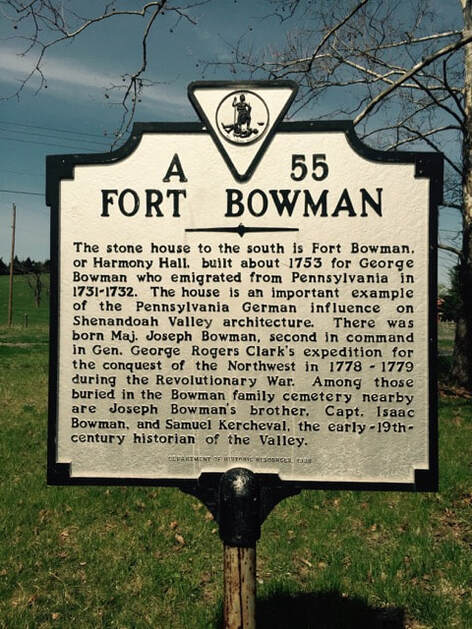

According the the affidavit, “He never was regularly mustered into or out of service," he said. "He never was discharged regularly. He received some little pay, but does not now recollect how much. He is unacquainted with the names of any Regular or Continental officers or companies, nor ever served with any.... He never was regularly enrolled in any company or corps, unless it might be Genl Clark’s or Col Hays’s. He belonged to none at home. He has no documentary evidence of his service; he knows of no living witness who can testify personally as to his service....” The death of Duncan's father was noted at the time by Daniel Boone, who collected the ball-head war club that had been used to kill him. War clubs were left by Indians as macabre calling cards beside their victims. Boone gave the club to Maj. Arthur Campbell who wrote to William Preston on October 1, 1774, "Mr. Boone preparing to go in search of the enemy...thinks it is the Cherokees that is now annoying us." This was at the height of Lord Dunmore's War, a conflict fought by Virginia primarily against the Ohio-based Shawnee over control of Kentucky. In 1905, David E. Johnston, a descendent of 1778 New River settlers, wrote, "The life of these people was a long and dangerous struggle.... A race of men unused to war and ever present dangers, would have been helpless before such foes as these wild beasts and the Indians. People coming from the old world, no matter how thrifty and adventurous, could not hold their own on the frontier.... Every man from childhood was accustomed to the use of the rifle, and even a boy at twelve years was regarded old enough to have a gun, and was soon taught how to use it. He at least could make a good fort soldier. The war was never ending, for even the times of so-called peace were broken by forays and murders. A man might grow from boyhood to middle age on the border, and yet never recall a single year in which some of his neighbors were not killed by the Indians." The pension affidavit, however, is great reading for anyone interested in early frontier history. It was transcribed by C. Leon Harris and is one of thousands Harris and his partners at RevWarApps.com have transcribed and put online. These affidavits have long been largely ignored by historians, who have been suspicious of them as the late memories of old men eager for money. Used carefully, however, they are a great resource to my research—especially when they corroborate each other or fill in blanks in the record. Duncan’s affidavit can be read here. Though he lived for a time in an area that recruited men for the 8th Virginia, Duncan was never connected with the regiment. (Updated May 31, 2021 and August 28, 2021.) More from The 8th Virginia Regiment Hidden in the woods down a long, steep and rocky dirt road near the intersection of Interstate 66 and U.S. Route 11 is a very old Virginia house that seems out of place. If you have an eye for regional architecture, you will notice that it looks much more like a Pennsylvania Dutch farmhouse than a Virginia plantation house. The house was built by George Bowman, a son-in-law of Jost Hite who led George and their extended family to the Shenandoah Valley from Pennsylvania in the 1730s. The house was long believed to have been built in the 1750s but may not be quite that old. The symmetrical features and chimney placements show concessions to dominant English architectural style of the time (Georgian). This is the house Colonel Abraham Bowman grew up in. George was his father. It is a very important early example of Pennsylvania German architecture in the Shenandoah Valley. The Laurence Snapp House (note the central chimney), which is nearby at Toms Brook, is another. The house has been called “Harmony Hall” since before the Revolutionary War. It is sometimes, however, called “Fort Bowman” because according to tradition it was used as a fort during the French and Indian War. Depending on the house's actual age, that history may now be in question.  A nearby Virginia historical marker mentions Abraham's brother, Joseph, but does not mention Abraham. There were in fact four brothers who lived here who served in the Revolutionary War in various capacities. They all had reputations as excellent horsemen, for which reason the siblings were known as the "four centaurs of Cedar Creek" after the nearby stream. In 2009, Maral Kalbian and Margaret Peters gave a presentation on the house’s history. Parts 1 through 3 cover the chain of property ownership. If you are not interested in that, you may want to start watching with part 4--which is embedded below. The house is now on property that is part of Cedar Creek & Belle Grove National Historical Park. Two more of Abraham Bowman's homes survive. The log house he built after moving to Kentucky in 1779 survives and has been restored, and the much larger plantation house he built after prospering there is also still standing. That house, now known as Helm Place, was later the home of Abraham Lincoln's sister-in-Law (Mary Todd Lincoln's sister). (Updated August 20, 2020) More from The 8th Virginia Regiment Bottles of Abraham Bowman whiskey on display at the distillery. (Author) Bottles of Abraham Bowman whiskey on display at the distillery. (Author) Abraham Bowman whiskey, which is produced in Fredericksburg, Virginia, is named for the only field officer who commanded the 8th Virginia for its entire two-year existence. Originally distilled by his descendants, the whiskey is an excellent tribute. Americans drank rum in colonial times. After the Revolution, however, they drank whiskey. Rum was made from Caribbean molasses, but whiskey was purely home-grown. “The Revolution meant the decline of rum and the ascendancy of whiskey in America,” writes Mary Miley Theobald. “When the British blockade of American ports cut off the molasses trade, most New England rum distillers converted to whiskey. Whiskey had a patriotic flavor. It was an all-American drink, made in America by Americans from American grain.” Nowhere was whiskey more popular than on the Virginia frontier. Whiskey came to America with the “Scotch Irish” who settled the frontier of Virginia, the same areas that produced the 8th Virginia Regiment. After the war, many 8th Virginia men led their families and neighbors into the woods of Kentucky. Abraham Bowman was among the very first to go. They began making whiskey out of corn, aging it in charred oak barrels, and (eventually) calling it "Bourbon."  A. Smith Bowman whiskeys age in the Fredericksburg warehouse. A. Smith Bowman whiskeys age in the Fredericksburg warehouse. Abraham Bowman was commissioned in 1776 to be the 8th Virginia’s original lieutenant colonel. A year later he was promoted to colonel to replace Peter Muhlenberg, who became a general. The Bowmans were not Scotch-Irish; they were German. Abraham was a third-generation American, however, and by his time or soon after there wasn’t much difference. After a few more generations, the Bowmans were back in the Old Dominion, and opened a whiskey distillery the day after Prohibition ended. For many years it was the only legal whiskey distillery in Virginia. The historical label is “Virginia Gentleman,” a serviceable bottom-shelf whiskey that is aged for just a few year. A. Smith Bowman Distillery, which was sold by the family to the Sazerac Company in 2003, also has a line of award-winning top-shelf whiskeys named after members of the family’s Revolutionary War generation: Bowman Brothers, Isaac Bowman, and John J. Bowman. These are the labels for the company’s small batch, port barrel finished, and single barrel labels. The Abraham Bowman label is reserved for experimental whiskeys that are released once or twice a year in small quantities. There have been cider finished, “double barrel,” wheat bourbon, vanilla bean infused, coffee finished, and port wine finished versions. The port finished bourbon won a “world’s best bourbon” award in 2016 and became a regular product under the Isaac Bowman label. Since then, a bottle of Abraham Bowman whiskey has become very hard to acquire. To get one, a person has to stand in line at the distillery on the day of release or win a lottery conducted by the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority. If you live in Virginia or are ever driving through the state on Interstate 95, can stop in and take a tour of the distillery. You can go home with a bottle of good whiskey, but don’t count on a bottle of Abraham Bowman. It’s a safe bet they’ll be sold out. (Updated 1/11/20)

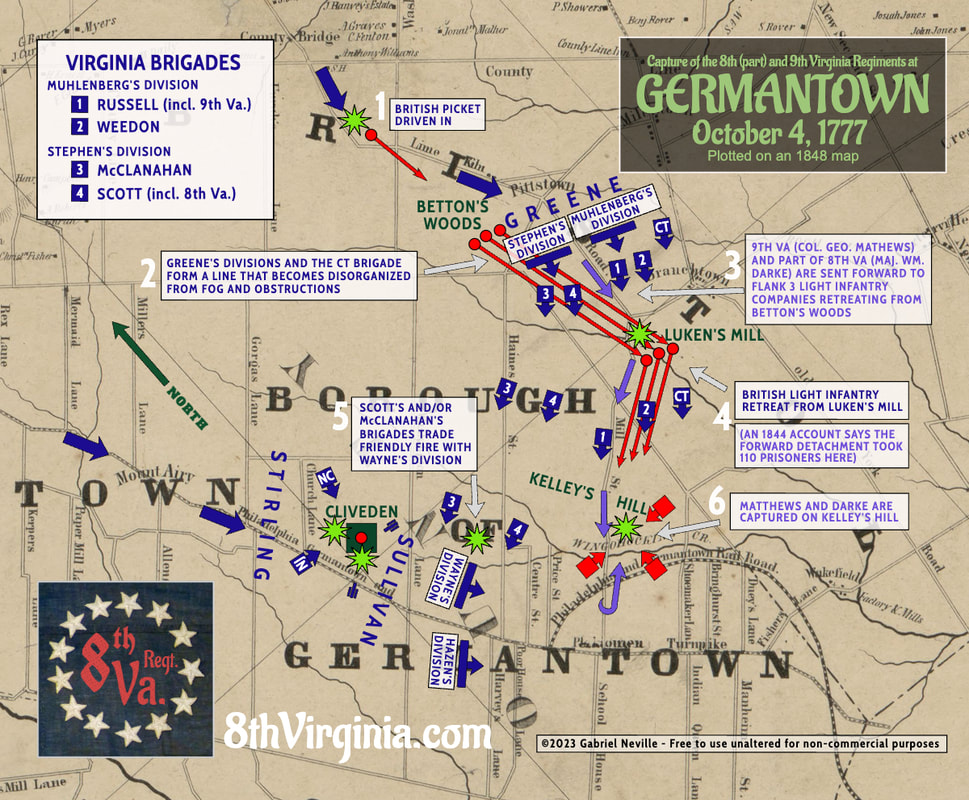

Two men, Richard Evans and Henry Saltsman of Captain Croghan’s company, were killed. Eleven men were wounded and three were never seen again. About forty men were captured, mostly in the companies commanded by captains Westfall, Slaughter, Croghan, and Higgins. Early in the engagement, Maj. Gen. Adam Stephen sent the 9th Virginia forward to flank three companies of retreating British light infantry. Deciding they needed support, he ordered the 8th Virginia to follow. The regiment's new and untested lieutenant colonel, John Markham from Chesterfield County, balked at the order. William Darke, the regiment's much more seasoned but also newly-promoted major, led half or more of the regiment forward to help their 9th Virginia comrades. They captured 110 of the light infantry (according to one account), but found themselves alone and unsupported as fog, smoke, fences, and friendly fire kept the brigades behind them from advancing in order. Matthews and Darke were captured. A little less than a third of the 9th Virginia was killed and the rest were captured. About forty 8th Virginia men were captured. We don't know how many of the regiment's other casualties came from his forward detachment or how many (if any) escaped back to the line. A lieutenant, Jacob Parrett, said he was "disabled by a wound in his right leg, just above the ancle, and it was with the greatest difficulty he secured himself during the retreat." Wounds in that era were not easy to recover from. In 1818, veteran Jonathan Grant reported that he “was wounded in the leg” at Germantown, “in consequence of which wound I am now rendered incapable of labouring for my support” and living “in reduced circumstances.” The men who were captured may have suffered the worst fate. They were carted off to the "new gaol," the Walnut Street Jail, in Philadelphia, where they were left hungry and cold going into winter. Officers were moved after a few days to the second floor of the State House (Independence Hall). Several men died in captivity and others never fully recovered from the experience. When he British gave up Philadelphia in 1778, they took their prisoners with them. There was an exchange of enlisted men in August of 1778, and some men went home (their enlistments had expired). Major Darke was exchanged in the fall of 1780 and made it home in time to participate in the Yorktown campaign.

|

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed