About three months before July 4, 1776, the regiment’s ten companies began to rendezvous in Suffolk, Virginia. Tidewater Virginia was abuzz with military affairs and politics. Lord Dunmore, the colonial governor, had fled the capital. From the safety of a British naval vessel, he had promised freedom to slaves who fled their masters and took up arms for the king. He met with British General Henry Clinton who had come south with a sea-born army of redcoats. Where those redcoats were headed was unclear. Williamsburg expected an attack at any time. When Clinton sailed south, the 8th Virginia was ordered to follow him (on foot), to counter him where ever he might attack. They departed just as Virginia’s defiant revolutionary assembly voted in favor of Independence on May 15, empowering its delegation to propose it in Congress. Less than a month later, Thomas Jefferson produced a Declaration for all the colonies asserting it to be “self-evident” that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” The Declaration of Independence, in reference to Canada and Ohio, accused the King and Parliament of “abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies.” The subtext here was that the King was abandoning the principles of the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and reverting to the tyranny of the old Stuart monarchs. The French were not Virginia’s only enemies. Of special relevance for the 8th Virginia was Jefferson’s charge that the King had "endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.” Most of the army's senior officers were veterans of the French and Indian War. Braddock’s defeat in 1755 had unleashed an era of conflict with the Indians in the Ohio Valley that would not really end until the War of 1812. There was already strong evidence that the King’s agents were stirring up the Cherokee and the Shawnee to create a two-front war for the Americans.

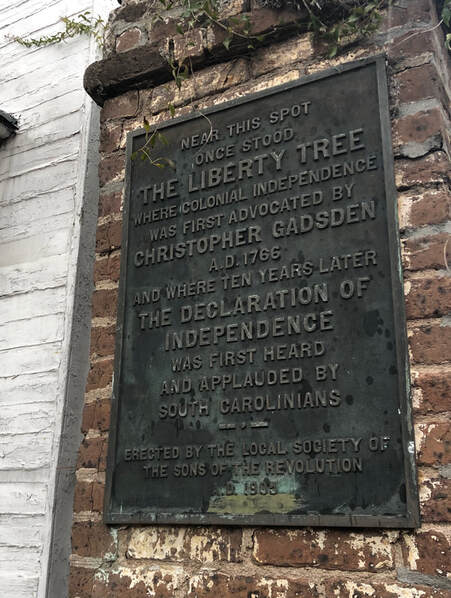

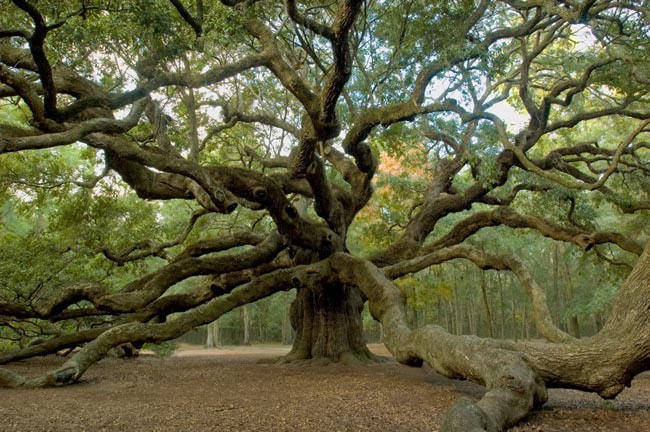

There was, according to Henry Laurens, a “Procession of President, Councils, Generals, Members of Assembly Officers & Military &c &c amidst loud acclamation of thousands.” The troops were assembled along with civilians. The tree was located north of town in an open area that would not be built on until after the war. “Thither the procession moved from the city…embracing all the young and old, of both sexes, who could be moved so far. Aided by bands of music, and uniting all the military of the country and city, in and near Charleston, the ceremony was the most splendid and solemn that ever had been witnessed in South Carolina.” No one seems to have noted the irony that the main speaker at the event was shaded and fanned by a slave as he expounded on liberty and freedom. It would take a long time for the full implication of the Declaration’s assertion that “all men are created equal” to penetrate American minds. For South Carolina and for Muhlenberg’s men, this was the high point of the war. The Battle of Sullivan’s Island was a tremendous victory that defied all odds and expert predictions. By the start of August, Americans had inflicted heavy blows upon the British regulars at Lexington and Concord, Ticonderoga, Bunker Hill, Great Bridge, Norfolk, Moore’s Creek Bridge, the siege of Boston, and now also at Charleston. The only major loss had been in Canada. The war was going well. America was winning and America had declared its independence. As summer turned into fall, however, fortunes changed. Washington suffered a series of major defeats in New York and New Jersey. The 8th Virginia marched on toward Florida on a mission they could not complete. The regiment’s mountain boys were already succumbing to the low country’s heat and ubiquitous mosquitos. For weeks, those mosquitos had been silently spreading malaria among the men. Those who had the weakest resistance, the ones born and raised in the Virginia mountains, began to die.  The Battle of Fort Moultrie, painted by John Blake White in 1826. Maj. Gen. Charles Lee is portrayed in the foreground with his arm outstretched toward Col. William Moultrie, who is holding a sword. The 8th Virginia did not participate in the defense of the fort, which was called Fort Sullivan until after the battle. (United States Senate) Learn more: Nic Butler, "Declaring Independence in 1776 Charleston" More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

4 Comments

|

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed