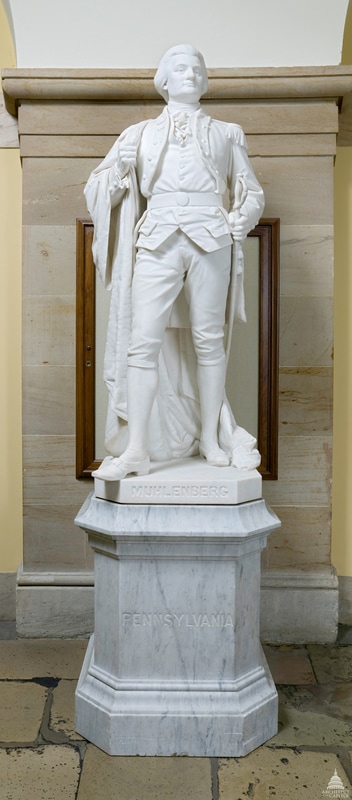

The second-most commonly-seen image is probably the statue that stands in the United States Capitol, one of two statues representing the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. This statue, which was created in 1889 by Blanche Nevin, hardly resembles the Trumbull and Martin Gallery portraits. It depicts Muhlenberg as the new colonel of the 8th Virginia Regiment, removing his pastor’s robe to reveal a military uniform. It appears to be a Continental Army uniform, which would be incorrect--the 8th Virginia was a Provincial Virginia regiment for the first several months of its existence. He may, in fact, have worn the same hunting shirt that his junior officers and enlisted men wore. This statue is the prototype for countless other images of Muhlenberg as a dashing young pastor surprising his congregation by revealing a uniform under his cloak. Neither his commission nor his uniform were in fact a surprise, though there is no reason to doubt the sermon.

Trumbull worked hard to make his depiction of the people in his history paintings as accurate as possible. He wrote that “to transmit to their descendants, the personal resemblance of those who have been the great actors in those illustrious scenes” was one of the goals of his patriotic painting. A war veteran from a prominent Connecticut family, Trumbull knew many of his subjects personally.

(Updated 9/17/21) More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

3 Comments

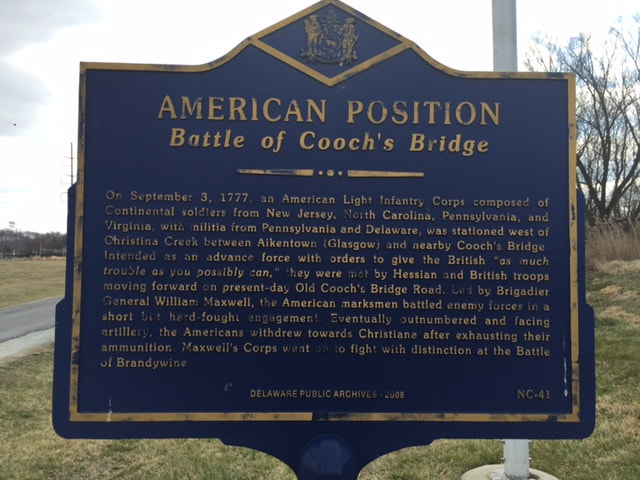

At the start of September, 1777, Washington was doing all he could to block the British advance on Philadelphia. He had four natural barriers to work with: the Christina River/White Clay Creek, the Red Clay Creek, the Brandywine River, and the Schuylkill River. Washington tried to use each of these barriers to block General Howe’s Army. The first effort was at the Battle of Cooch’s Bridge, where William Maxwell’s light infantry (an elite, but temporary unit) engaged a much larger Hessian and and British advance guard. The 8th Virginia’s Captain William Darke led a contingent of men from General Charles Scott’s Brigade (including 28 men from the 8th Virginia). One of his men, William Walker, later complained that “no historian” had noticed the “very bloody conflict,” and declared, “For myself I can say that this detachment on that day deserved well of their country.” Cooch’s Bridge is still not well remembered. But for those who are interested, the site is well-marked and reasonably intact. The Cooch family has preserved much of the surrounding land for more than two centuries. The folks at the Pencader Heritage Are Association are doing a great job making sure the story is remembered and told. Their ten-year old museum, the Pencader Heritage Museum, has excellent displays and is staffed by volunteers who are eager to tell the story of the September 3, 1777 battle and other events in local history. Admission is free, but the museum is only open on the first and third Saturdays of each month. It is a very easy stop off of I-95 if you ever happen to be traveling that way on the right Saturday. Outdoor markers by the museum and battle site are worth the visit even if the museum is closed. The museum gets absolutely no government support—so think about lending it some of yours! |

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed