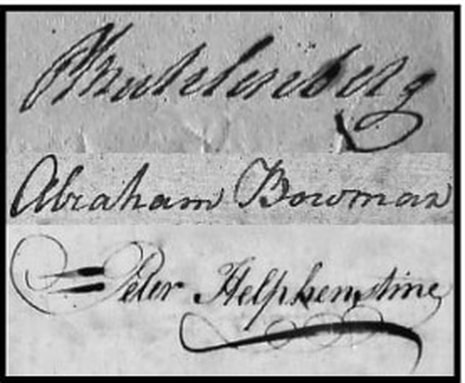

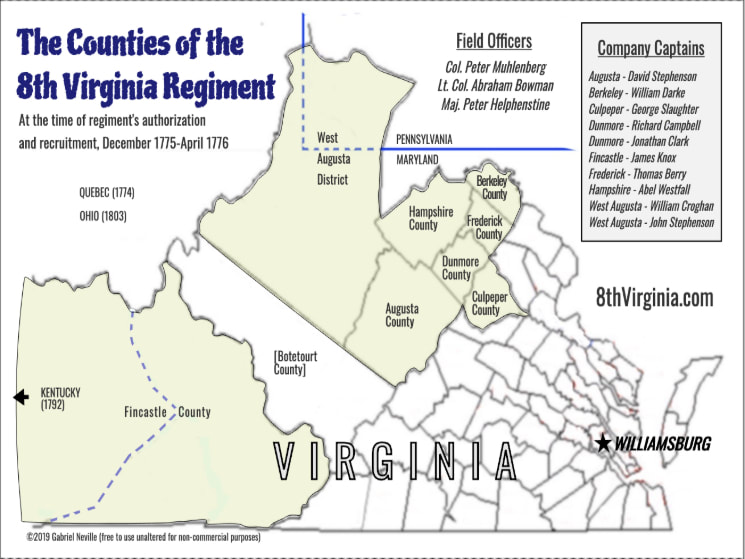

The signatures of Col. Peter Muhlenberg, Lt. Col. Abraham Bowman, and Maj. Peter Helphenstine. (Author) The signatures of Col. Peter Muhlenberg, Lt. Col. Abraham Bowman, and Maj. Peter Helphenstine. (Author) Why Germans? The 8th Virginia Regiment of Foot was authorized by the revolutionary Virginia Convention on December 13, 1775. It had no numeric designation yet, but was intended to be unique in two ways. It would be ethnically-based and all of its men would carry rifles. It was conceived as a “battalion” to “be composed of Germans, with German officers.” The concept may have originated with the Rev. Peter Muhlenberg and Jonathan Clark, both delegates from Dunmore County in the Shenandoah Valley. Dunmore (now called Shenandoah County) was the cultural hub of German life in the Valley. It is inconceivable that the resolution could have been drafted without the involvement of at least Muhlenberg and probably of Clark as well. Muhlenberg was the Rector of Beckford Parish, the geography of which was identical to that of Dunmore County. His church was at Woodstock, the county seat. He was, however, more than just the community’s pastor. He was the son of the patriarch or the Lutheran Church in America, whose church was in the village of Trappe near Philadelphia. Clark was the county’s deputy clerk, an important job, under Thomas Marshall (soon to be colonel of the 3rd Virginia Regiment and father of future Chief Justice John Marshall). The Shenandoah Valley’s Germans had nearly all come the way Muhlenberg had: down the Great Philadelphia Wagon Road to Virginia. The road passed through communities that remain heavily German to this day, such as Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Scotch-Irish immigrants followed the same route, but tended to settle farther south in the Valley, around Staunton and Augusta County. Lutheran Germans like Muhlenberg were seen by the Virginia gentry as reasonably reliable and trustworthy. Their theology differed little from the Church of England. Muhlenberg had, in fact, gone to London to be ordained before taking his position in Woodstock. (King George III was himself of German descent and his great grandfather, George I, couldn’t speak English when he took the throne.) The Ulster Irish, however, were less trusted. They were theological dissenters and often politically radical. Their Calvinist faith differed in important ways from Anglicanism. They could, however, be counted on to fight “And be it farther ordained,” read the resolution, “That of the six regiments to be levied as aforesaid, one of them shall be called a German regiment, to be made up of German and other officers and soldiers, as the committees of the several counties of Augusta, West Augusta, Berkeley, Culpeper, Dunmore, Fincastle, Frederick, and Hampshire (by which committees the several captains and subaltern officers of the said regiment are to be appointed) shall judge expedient.”

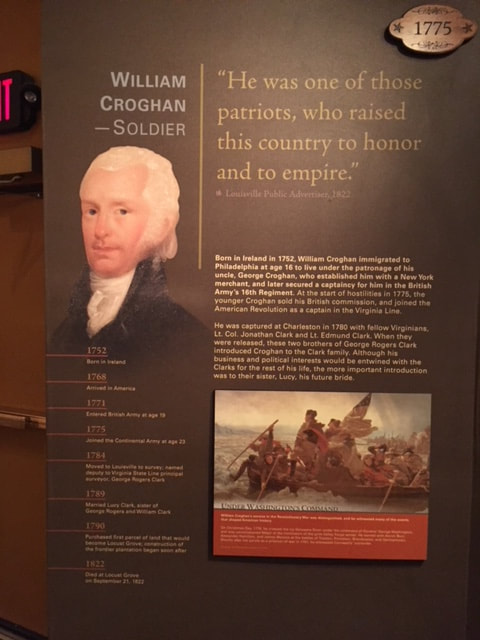

Below them, the officers of the ten companies—captains, lieutenants and ensigns—were a diverse group. English, German, and Scotch-Irish were most common. Capt. Abel Westfall of Hampshire County was Dutch, though his family had been in America for generations. Lieut. Jacob Rinker was Swiss. Lieut. Isaac Israel was Jewish. Religiously, though it is hard to trace, they were mostly Anglican, Lutheran, German Reformed, Presbyterian, and probably Baptist. If there were no Methodists, some of them—including Capt. Westfall—would become Methodists soon. ` The diversity of the officers reflected the diversity in the rank and file. The 8th Virginia was a microcosm of the Continental Army at large. It was America’s original “melting pot.” Originally divided by race and religion, their shared hardships would soon make them a band of brothers. The committees were generally dominated by English elites and could be counted on to appoint the right kind of company officers. Only two of ten companies had Irish captains: Fincastle County and the West Augusta district (both on the frontier) selected James Knox and William Croghan. Both were capable and loyal officers. The choice of field officers, however, was up to the Virginia Convention and it chose three Germans as it had planned. Each was from a different down in the lower (northern) Shenandoah Valley. Muhlenberg was appointed to be the colonel. Abraham Bowman of Strasburg (also in Dunmore County) was appointed to be the lieutenant colonel. Bowman came from a prominent family. His grandfather, Jost Hite, had led the first group of German settlers into the valley from Pennsylvania in 1731. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

1 Comment

The tomb of Adam Stephen in Martinsburg, West Virginia. Tunnels beneath his nearby house have yet to reveal whatever secrets they may hold. (Gabe Neville) The tomb of Adam Stephen in Martinsburg, West Virginia. Tunnels beneath his nearby house have yet to reveal whatever secrets they may hold. (Gabe Neville) Maj. Gen. Adam Stephen was the 8th Virginia's division commander in 1777, leading them at the battles of Brandywine and Germantown. He worked closely with George Washington for more than two decades, sometimes challenging and undercutting him. He ran against Washington for the House of Burgesses and almost ruined the surprise Christmas, 1776 attack on Trenton by sending soldiers across the river to settle a personal vendetta against the Hessians. He was reportedly drank too much, and was finally court-martialed and cashiered from the Army after the disaster at Germantown. That did not end his life of civic engagement, though. He founded Martinsburg (now in West Virginia) and served in the Virginia convention that ratified the U.S. Constitution. Sometime during the war, he built a fine house for himself where Martinsburg grew up. Intriguingly, he built his house over the mouth of a cave. According to tradition, this was done to prove an escape in case of an attack by Indians or other enemies. Since that era, the cave has been filled in with dirt, leaving a persistent mystery: where does the natural underground tunnel lead? For nearly twenty years, TriState Grotto--a local caving club--has been working to excavate the passage, one five-gallon bucket at a time. Videos of their progress (and archeological finds) have been posted occasionally on YouTube. Here they are, in chronological order. Stephen died in 1791 and is buried under a rustic monument not far from his home. Despite the controversies associated with his life, he served his country at important moments and in important ways. He was with Washington at Jumonville Glen, Fort Necessity, and Braddock's Defeat years before his Revolutionary War service. His French and Indian War waistcoat and gorget are in the Smithsonian. Aside from his legacy of service and these artifacts, he left an enduring mystery beneath his house. One day soon, perhaps, we'll know where the tunnel leads. More from The 8th Virginia Regiment

After wasting much of the spring of 1777 trying to lure Washington’s army out of the Watchung Mountains, General Howe moved his army out of New Jersey and back to Staten Island. The preceding twelve months included the battles of Long Island, Harlem Heights, White Plains, Trenton, Assunpink Creek, Princeton, and Short Hills, but Howe was now literally back where he had begun. Together, the eight battles had earned the British little more than possession of Manhattan.

More from The 8th Virginia Regiment I’ve written twice before about Private William Eagle, who enlisted into the 8th Virginia late in 1777 and joined at Valley Forge just before the two-year enlistments of the original men expired. He was evidently just 16 years old. He was the son of very early settlers of Pendleton County, West Virginia’s remote Smoke Hole Canyon and returned there after the war. He was buried in the beautiful canyon facing a remarkably vertical rock formation that now carries his name: Eagle Rock. Over the years Smoke Hole Canyon became a pocket of Unionism in a region of otherwise intensely pro-Confederate sentiment, a haven for moonshiners, and eventually part of the Monongahela National Forest. His grave, perhaps not permanently marked, was lost for many years until discovered by Forest Service surveyors about 1930 when a new stone was set in the ground. Photos of the spot on the internet show a pretty and bucolic setting. The stone sits under a sycamore tree and appears well-attended with a crisp and clean American flag. Returning recently from a family vacation, however, I stopped by the site and discovered that it looks nothing like those images. In mid-January the stone was half-buried in frozen debris at the end of a virtual river of ice descending from the ridge of North Fork Mountain. The base of the sycamore’s trunk is rotting. It looks as though an impromptu hiking trail has become a path for water runoff. On a 20-degree day following two days of rain, Private Eagle’s grave was covered by forest debris that had washed down the mountain. Attempts to clear it were fruitless. It was frozen solid. Perhaps this is a purely seasonal phenomenon, but a Revolutionary War veteran’s grave deserves better care. It appears to me that thoughtless hikers are the culprits. Someone—the Forest Service, Pendleton County, neighbors, a Boy Scout looking for an Eagle Scout project, the DAR or the SAR—should find a way to protect the grave from what seems like inevitable serious damage.

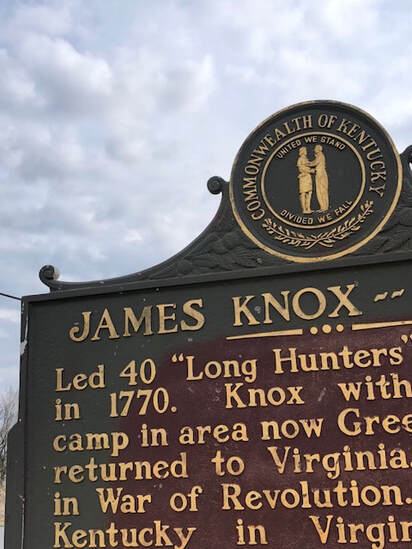

He then led the Fincastle (Kentucky) County company for the 8th Virginia in 1776. After his company was decimated by malaria in south, he was detached to lead a new company in Morgan’s Rifles and took part in the first major American victory of the war at Saratoga. After the war, he served in the legislatures of Virginia and Kentucky (after it separated from Virginia) and served in the Kentucky militia as a colonel. In 1805 he married the widow of his neighbor and friend, Benjamin Logan.

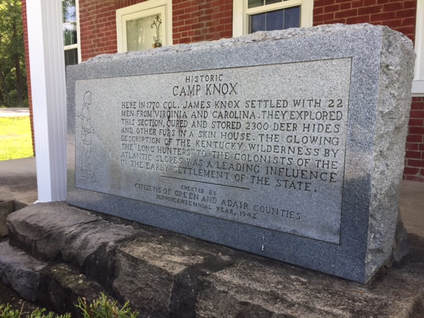

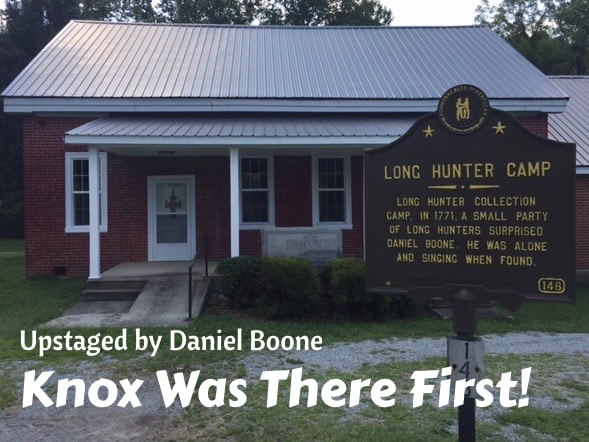

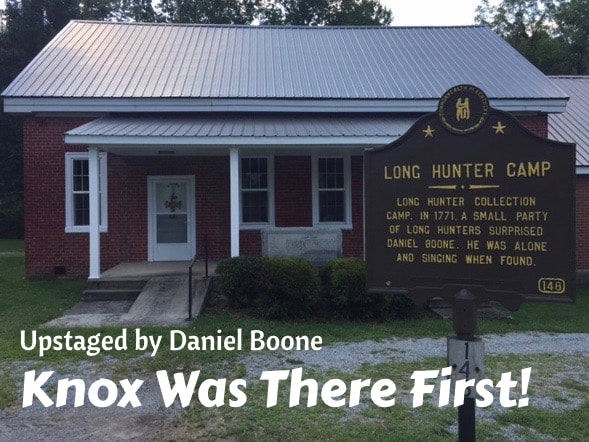

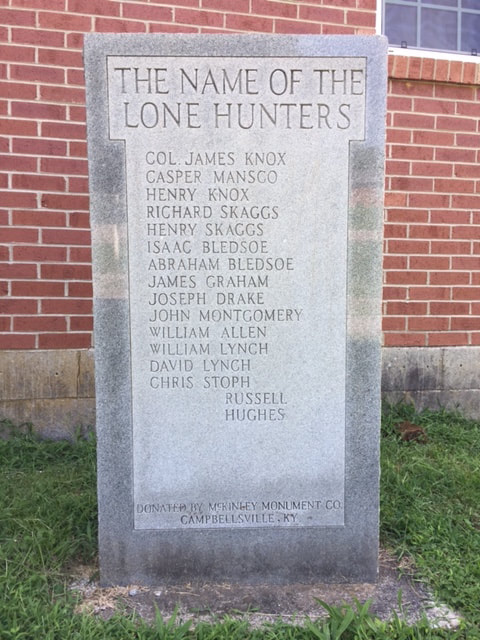

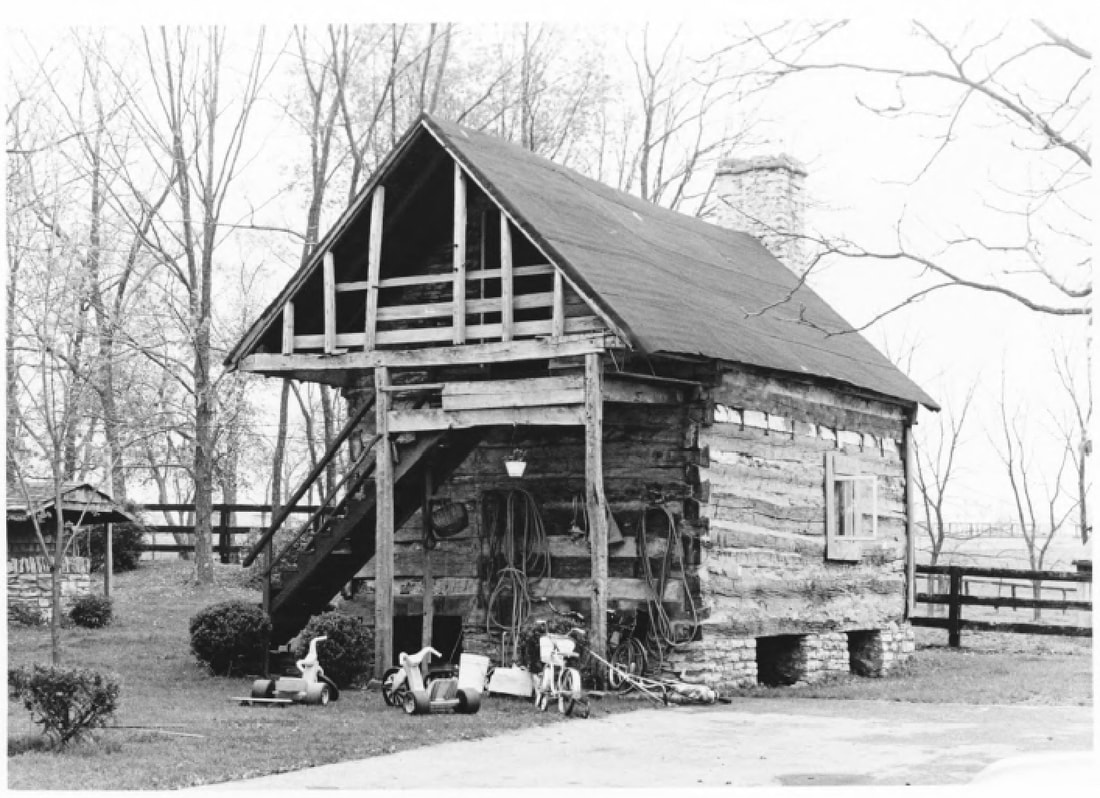

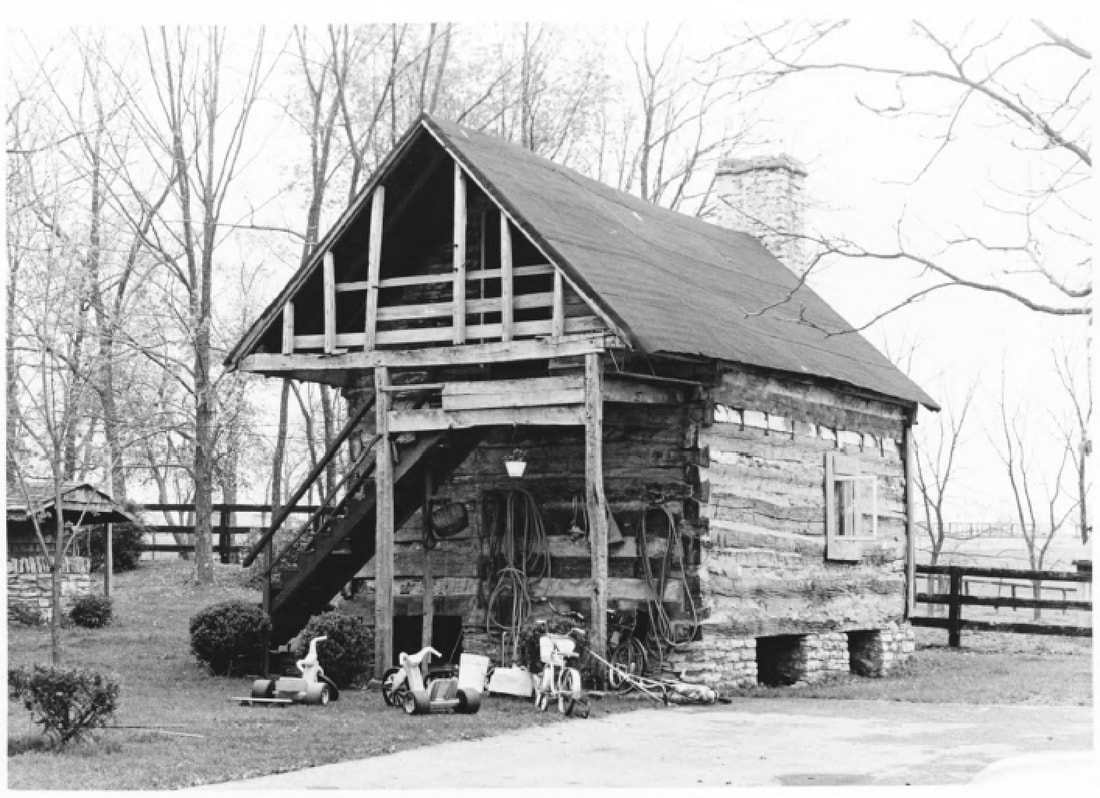

I drove by the creek one more time and looked high up on the bluff on the opposite side. Through the trees, I could just make out a monument. Looking on my phone at pictures on FindAGrave.com, I decided it looked like Benjamin Logan’s grave marker. Knox’s grave is up there too, but can’t be seen from the road. The Logan cemetery was cleaned up in 2015. Already “neglected and overgrown” in 1923, it was described in 2015 as “in complete disrepair; you couldn’t even walk through it, you had to spread the trees and the bushes and the vines apart to even get through it.” My search for Knox’s grave is a perfect allegory for the story of the 8th Virginia. The story is out there, but it’s frequently very hard to find. Read More: "James Knox Was There Before Daniel Boone" (8/19/17) (Updated 1/27/21) More from The 8th Virginia Regiment Locust Grove, built by 8th Virginia Captain William Croghan about 1792. Locust Grove, built by 8th Virginia Captain William Croghan about 1792. No other place does more to tell the story of the 8th Virginia Regiment than the house and museum at Locust Grove, near Louisville, Kentucky. It does this almost unintentionally. Locust Grove was the after-war home of Captain William Croghan (who was a major when the war ended). He married the sister of fellow 8th Virginia Captain Jonathan Clark and lived not far from Clark at the fall-line of the Ohio River (Louisville). This was a roughly 400-mile boat ride from his old home at Pittsburgh.For many 8th Virginia men, the opening up of Kentucky was their main reason for fighting in the war. Colonel Abraham Bowman, captains Croghan, Clark, James Knox, and George Slaughter all moved to Kentucky after (or during) the war. So did a large number of the regiment’s junior officers and enlisted men. I have compared this research to a jigsaw puzzle—the compilation of thousands of discrete bits of information from a multitude of sources. It was a bit of a shock, therefore to visit Locust Grove and find a place that seemed in so many ways to be a memorial to the 8th Virginia Regiment and its veterans. It isn’t actually that, of course. I don't think the regiment itself is even mentioned. Much more is said about Croghan's brother-in-law George Rogers Clark. But the museum’s exhibits wonderfully contextualize and illustrate the world of the 8th Virginia, before, during and especially after the war. Croghan was a very important man in Kentucky. He had money, land, and relationships. Much or most of that—including his marriage—came to him through his service in the war. The same could be said for many of his 8th Virginia comrades who prospered in the west. It was in large measure what they fought for during the Revolution: opportunity.  8th Virginia Captain James Knox was one of the original "long hunters," the first white men to go deep into "Kentucky country" through Cumberland Gap. 8th Virginia Captain James Knox was one of the original "long hunters," the first white men to go deep into "Kentucky country" through Cumberland Gap. The adventures of 8th Virginia Captain James Knox have been unfairly overshadowed by those of Daniel Boone. This may be true generally, but it is definitely—and literally—true at the site of a memorial marker in Greene County, Kentucky. The 8th Virginia’s recruitment area was vast—covering almost the entire Virginia frontier, which at that time stretched from Pittsburgh to the Cumberland Gap—a distance of 450 miles. Those two places were, at that time, the only practical access points to the “Kentucky Country”—all of which was, at the start of the war, part of Fincastle County, Virginia. To get there, you could float down the Ohio River from Pittsburgh, or you could travel overland through the Cumberland Gap. Few had taken the latter route, however, when James Knox led a hunting party that way in 1770. Knox was one of the original “Long Hunters,” who entered Kentucky on months-long or even years-long hunting trips, intending to return with large quantities of pelts. Daniel Boone is by far the most famous of the long hunters, but that is partly because there is only room for one of these little-remembered adventurers in public memory. In 1770, James Knox and his team established a hunting camp and pelt repository (a “skin house”) by the north bank of a creek now known as Skinhouse Branch. Years later, a church was built on the same site. Today, the 187-year old nondenominational church sits at the intersection of Skinhouse Branch and Long Hunters Camp roads—neither of which carries enough traffic to warrant painted markings. It is surrounded by farms growing corn, tobacco, and soybeans. Two stone markers were put there long ago by local citizens to memorialize James Knox and the hunting expedition of 1770. In front of them, and closer to the road, is an official Kentucky state historic marker noting that Daniel Boone was also there—a year later. Early in 1776, Knox recruited one of the 8th Virginia’s ten companies. His men were decimated by malaria during the South Carolina expedition of that summer and fall. By the spring of 1777, only a handful were left. Knox became a captain in Morgan’s Rifles and commanded a company at the victory at Saratoga. He took a few of his 8th Virginia men with him, and his 8th Virginia Regiment company ceased to exist. He was a prominent citizen of Kentucky in his later years, but has always been overshadowed by Daniel Boone. Read More: "Searching for Captain Knox" (3/29/18)  Colonel Abraham Bowman's Kentucky cabin in 2017, as restored circa 2002. Colonel Abraham Bowman's Kentucky cabin in 2017, as restored circa 2002. 8th Virginia Colonel Abraham Bowman’s frontier cabin looks better than has in 200 years. Frontier log cabins, usually built of American Chestnut on stone foundations, were very durable structures. A surprising number of them survive today, including the cabin 8th Virginia Colonel Abraham Bowman built about 1779 or 1780 when he moved to Kentucky. Nevertheless, after two centuries, the Bowman cabin showed signs of deterioration (and alteration) when images of it were submitted to the National Park Service in 1979. Bowman and his brothers are remembered as accomplished equestrians, reportedly known back in the Shenandoah Valley as the “Four Centaurs of Cedar Creek.” Appropriately, most of his land in Kentucky is now part of one of the most important equestrian facilities in the world. His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the Emir of Dubai and Prime Minister of the United Arab Emirates, is a horse enthusiast and owner of a global thoroughbred stallion operation which stands stallions in six countries. Soon after acquiring the property in 2000, Sheikh Mohammed had the Bowman cabin repaired and restored, along with other properties built long ago for Bowman’s children. The unique cabin, which features a basement and an exterior staircase to a second floor, has never looked better. The most notable change from the restoration is the reorientation of the exterior stairs, presumably to their original position and providing more headroom over the basement stairs.  An undated photo of Colonel Abraham Bowman's Kentucky cabin. The car parked next to it suggests the image dates from the 1960s. (findagrave.com) An undated photo of Colonel Abraham Bowman's Kentucky cabin. The car parked next to it suggests the image dates from the 1960s. (findagrave.com) Near Lexington, Kentucky, there is a Greek revival house, built in the early 1800s called “Helm Place.” Originally called “Cedar Hall,” the house was built either by 8th Virginia Colonel Abraham Bowman or his son. In documentation submitted to add it to the National Register of Historic Places, the building is described as “impressive." It “sits on a hill overlooking the South Elkhorn and gives one the impression of a Greek Temple.” The Bowman family prospered in Kentucky. They began as pioneers, however, and lived originally in pioneer fashion. Colonel Bowman’s first Kentucky home, a log cabin, survives just a quarter mile from Helm Place. “The cabin,” says the National Register paperwork from 1979, “a single-pen log structure with half-dovetail notching…faces southeast. There is a step-shouldered stone chimney on the south side and the exterior stair to the loft on the opposite end. The significant details of half-dovetail joinings of the logs and the outside staircase date this building to the late 1780s. The half-dovetail joining was characteristic of other log houses in this part of the state. The log house is also unique in that it contained a stone basement, which, in effect, created a three-story building.” A log cabin is not the sort of structure one might expect to survive for more than two centuries. Nonetheless, stone foundations and clapboard coverings have protected many of these pioneer dwellings into the 21st century. Here is an earlier post about 8th Virginia Captain Robert Higgin's cabin in Moorefield, West Virginia.  Monument Park in the town of Fort Lee, New Jersey, marks the spot of the historic fort. (Author) Monument Park in the town of Fort Lee, New Jersey, marks the spot of the historic fort. (Author) On September 22, 1776, William Croghan’s detachment of men from the 8th Virginia arrived at Fort Constitution, high on a cliff looking over the Hudson River and the island of Manhattan. Very soon, they would be part of the most famous campaign of the war. Months earlier, when the 8th Virginia first formed, its ten companies were ordered to rendezvous at Suffolk, Virginia—south and across the James River from the provincial capital at Williamsburg. Those from the far frontier were the last to arrive. Captain James Knox’s company from Fincastle County (now the state of Kentucky and parts of far southwest Virginia) arrived just in time to join the Regiment as it headed south to with General Charles Lee to defend Charleston. Captain William Croghan’s company from Pittsburgh came too late. His company and several dozen stragglers from other companies were attached for the season to the 1st Virginia and sent north to reinforce Washington at New York. After a march that took more than a month, the 1st Virginia arrived at a fort overlooking the Hudson. It was called Fort Constitution, but was soon renamed Fort Lee after General Charles Lee got (only partially deserved) credit for the glorious June 28 victory at Sullivan's Island in South Carolina. Fort Lee was commanded by Gen. Nathanael Greene and, with Fort Washington across the river, was charged with maintaining patriot control of the strategically critical waterway.  The George Washington Bridge spans the Hudson River between the sites of Fort Lee and Fort Washington. The two forts guarded the strategically important waterway. (Author) The George Washington Bridge spans the Hudson River between the sites of Fort Lee and Fort Washington. The two forts guarded the strategically important waterway. (Author) Sergeant William McCarty recorded their arrival. After ferrying across the Passaic River they “marched to the fort, which we came by several camping places and camps on top of a high hill by the North [Hudson] River.” They “halted in sight of the fort and river till Colonel [James] Read [of the 1st Virginia] went to speak to General Greene.” He “returned shortly” and “ordered us to march back up the hill a piece, where it was late when we pitched camp.” For the next few days, the roughly 140 8th Virginia men under Captain Croghan rested and celebrated after their long march. They were issued flour, beef and rum. They got paid for the first time. On the third day there, McCarty wrote “We lay there and our men drunk very hard as they had plenty of money.”  A reconstructed artillery emplacement overlooks Manhattan from the Palisades. (Author) A reconstructed artillery emplacement overlooks Manhattan from the Palisades. (Author) Things soon turned serious, however. The day after their arrival, soldiers across the river were assembled to witness the execution of a man—bound, blind-folded, and kneeling—for cowardice (Washington gave him a last-minute reprieve). In addition to that news, Croghan’s men also learned that the Hessians and Scottish Highlanders had given no quarter at the Battle of Long Island the month before and had shot as many as seventeen Americans in the head after they had surrendered at Kip’s Bay. If they did not already know it, they now understood that there was no romance in war. Four days after their arrival, still at Fort Lee atop the Jersey Palisades, they watched British maneuvers in the river below. McCarty wrote, “The force heard the cannon fire very brisk from the shipping of the English, and we could see them land. We could easy see their camps and every turn they would make.”  A reconstructed block house with a modern skyscraper looming behind it. (Author) A reconstructed block house with a modern skyscraper looming behind it. (Author) Their stay at the fort was brief. Private Jonathan Grant later attested that they traveled through the Jerseys “to fort Lee on the North River & thence crossed the River to Fort Washington. The enemy at that time was in New York.” Similarly, Private Henry Gaddis recalled that they traveled “to Fort Lee, then we crossed over the North river to Fort Washington.” They joined the 3rd Virginia to form a small, temporary brigade commanded by Col. George Weedon. Now part of the main arm, they were thrust into battle—first at White Plains and later at Trenton. In January, only a handful of them were still well enough to participate in the critical victory at Princeton. The site of Fort Lee and its surrounding camps and artillery emplacements have been partially preserved. Judging purely from McCarty’s account it appears that much of the camping area has been blasted away to make room for the George Washington Bridge. Some of what remains has been preserved as Fort Lee Historic Park. The visitor center and its displays date from the 1976 Bicentennial and, though a bit worn down, still tell the story well. Reconstructed buildings and artillery batteries illustrate the site’s purpose despite the massive bridge and surrounding skyscrapers that make the area look very different from they way it was in the fall of 1776. The position of the actual fort is in the middle of the town of Fort Lee and called Monument Park. An artistic monument records the presence of the fort and the events that occurred there. Fort Lee was abandoned during the retreat through New Jersey, a retreat the fort’s namesake pointedly did nothing to assist with. Lee was in fact captured by the enemy and began to advise them on how to defeat the Continentals—a story told in this earlier post. One has to wonder how many people who live in Fort Lee today have any idea that their town is named for a traitor. Read More: Fort Lee's Despicable Namesake More from The 8th Virginia Regiment |

Gabriel Nevilleis researching the history of the Revolutionary War's 8th Virginia Regiment. Its ten companies formed near the frontier, from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

© 2015-2022 Gabriel Neville

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed