- Published on

The Cost of Fog and Drunkenness

October 4, 1777 was a bad day for the 8th Virginia and the Continental Army.

Colonel Bowman’s men had seen combat, most notably at Brandywine—but disease and cold had caused more casualties than enemy musket balls or bayonets. The Battle of Germantown was different. Confused by fog and under the command of an allegedly drunk major general, the 8th Virginia suffered more battlefield casualties in one day than the rest of its service combined.

Colonel Bowman’s men had seen combat, most notably at Brandywine—but disease and cold had caused more casualties than enemy musket balls or bayonets. The Battle of Germantown was different. Confused by fog and under the command of an allegedly drunk major general, the 8th Virginia suffered more battlefield casualties in one day than the rest of its service combined.

Two men, Richard Evans and Henry Saltsman of Captain Croghan’s company, were killed. Eleven men were wounded and three were never seen again. About forty men were captured, mostly in the companies commanded by captains Westfall, Slaughter, Croghan, and Higgins.

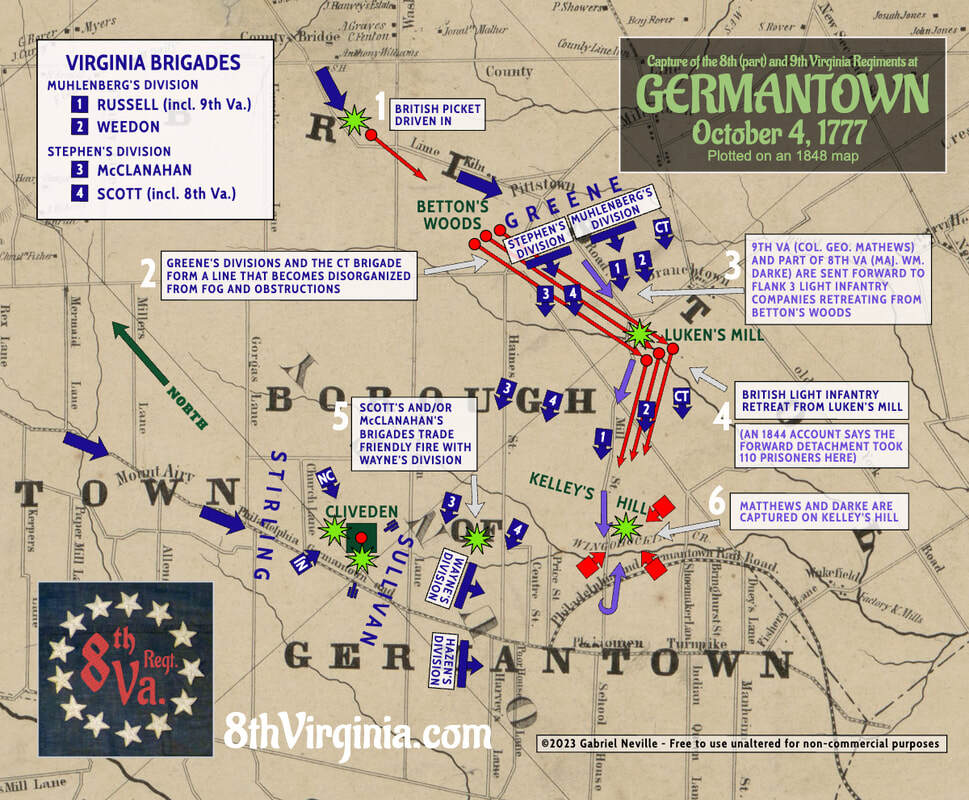

Early in the engagement, Maj. Gen. Adam Stephen sent the 9th Virginia forward to flank three companies of retreating British light infantry. Deciding they needed support, he ordered the 8th Virginia to follow. The regiment's new and untested lieutenant colonel, John Markham from Chesterfield County, balked at the order. William Darke, the regiment's much more seasoned but also newly-promoted major, led half or more of the regiment forward to help their 9th Virginia comrades. They captured 110 of the light infantry (according to one account), but found themselves alone and unsupported as fog, smoke, fences, and friendly fire kept the brigades behind them from advancing in order. Matthews and Darke were captured. A little less than a third of the 9th Virginia was killed and the rest were captured. About forty 8th Virginia men were captured. We don't know how many of the regiment's other casualties came from his forward detachment or how many (if any) escaped back to the line.

A lieutenant, Jacob Parrett, said he was "disabled by a wound in his right leg, just above the ancle, and it was with the greatest difficulty he secured himself during the retreat." Wounds in that era were not easy to recover from. In 1818, veteran Jonathan Grant reported that he “was wounded in the leg” at Germantown, “in consequence of which wound I am now rendered incapable of labouring for my support” and living “in reduced circumstances.”

The men who were captured may have suffered the worst fate. They were carted off to the "new gaol," the Walnut Street Jail, in Philadelphia, where they were left hungry and cold going into winter. Officers were moved after a few days to the second floor of the State House (Independence Hall). Several men died in captivity and others never fully recovered from the experience. When he British gave up Philadelphia in 1778, they took their prisoners with them. There was an exchange of enlisted men in August of 1778, and some men went home (their enlistments had expired). Major Darke was exchanged in the fall of 1780 and made it home in time to participate in the Yorktown campaign.

Early in the engagement, Maj. Gen. Adam Stephen sent the 9th Virginia forward to flank three companies of retreating British light infantry. Deciding they needed support, he ordered the 8th Virginia to follow. The regiment's new and untested lieutenant colonel, John Markham from Chesterfield County, balked at the order. William Darke, the regiment's much more seasoned but also newly-promoted major, led half or more of the regiment forward to help their 9th Virginia comrades. They captured 110 of the light infantry (according to one account), but found themselves alone and unsupported as fog, smoke, fences, and friendly fire kept the brigades behind them from advancing in order. Matthews and Darke were captured. A little less than a third of the 9th Virginia was killed and the rest were captured. About forty 8th Virginia men were captured. We don't know how many of the regiment's other casualties came from his forward detachment or how many (if any) escaped back to the line.

A lieutenant, Jacob Parrett, said he was "disabled by a wound in his right leg, just above the ancle, and it was with the greatest difficulty he secured himself during the retreat." Wounds in that era were not easy to recover from. In 1818, veteran Jonathan Grant reported that he “was wounded in the leg” at Germantown, “in consequence of which wound I am now rendered incapable of labouring for my support” and living “in reduced circumstances.”

The men who were captured may have suffered the worst fate. They were carted off to the "new gaol," the Walnut Street Jail, in Philadelphia, where they were left hungry and cold going into winter. Officers were moved after a few days to the second floor of the State House (Independence Hall). Several men died in captivity and others never fully recovered from the experience. When he British gave up Philadelphia in 1778, they took their prisoners with them. There was an exchange of enlisted men in August of 1778, and some men went home (their enlistments had expired). Major Darke was exchanged in the fall of 1780 and made it home in time to participate in the Yorktown campaign.

After the Battle of Germantown, the 8th Virginia's new lieutenant colonel, John Markham, was charged with "Having left the regiment in time of action ... and also, on the retreat of the same day" and with "Delay when ordered to support the advanced guard." A court martial unanimously found him guilty and he was cashiered. General Stephen was also tried, found guilty of drunkenness and poor leadership, and kicked out of the army.

[Post Updated 10/5/19 and 1/4/23.]

[Post Updated 10/5/19 and 1/4/23.]

Artist Howard Pyle's rendering of the attack on Chew House during the Battle of Germantown. The 8th Virginia did not participate in this part of the battle.

7 Comments

Where is this Germantown at?

It's in Philadelphia.

Nice slice of history, Gabe. I always enjoy them.

Gabe, is this the same Germantown battle in which Robert Higgins was captured?

One and the same!

Each year Historic Germantown (which includes the still standing Chew home named Cliveden) hosts the Revolutionary Germantown Festival in the first Saturday of October (Oct. 5, 2024), where there is a re-enactment (or there used to be) of the Battle of Germantown and tours of all the historic homes involved (and yes, you really can still see the blood spot in the floor at the Grumblethorp mansion!)

Thanks Gabe! Interesting as always.