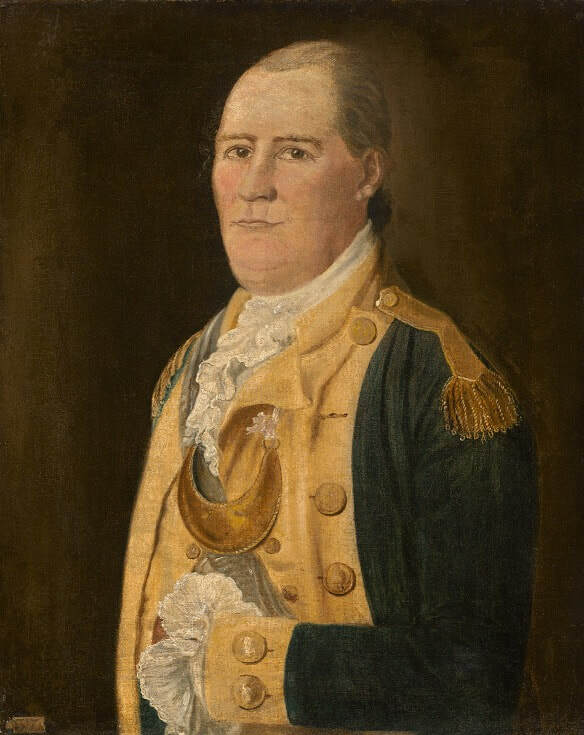

Sir,

I recd the letter you did me the honor to write me by Colo Rootes and in compliance therewith shall March with what Volunteers I have in a day or two. I flatter my self you, Sir, will not think my time has been mispent, when I asure You I have been exerting every nerve to get Men into the field who would be of service when there. ◊ "Colo Rootes" may be George Rootes, who represented Frederick County in the First Virginia Convention in 1776. Nelson succeeded Jefferson as governor on June 12th. He wrote to Morgan from Staunton (where the state government had retreated).

You, Sir, are well acquainted with the Enemy’s superiority in Cavalry and the absolute necesity there is for as many horse as We can mount; this has induced me to endeavour to raise three troops mounted on the best horses these Counties can produce; such a reasonable supply will be of the utmost consequence, and their remaining three months will give time for a more permanent establishing of Dragoons, the part of an army not to be dispensed with; to attain this desirable purpose, my self with a number of other Gentlemen, have engaged our selves to some people in Frederick Town in Maryland, for such accoutrements as could be hastily furnished, for payment whereof, we make no doubt, provision will be made, when the accounts are rendered; such necessaries are allways greatly wanted, and when the volunteers times have expired, they will remain to equip future Dragoons; The horses will be an acquisition, the Country will find very beneficial. ◊ This appears to be the point of contention between Morgan and the governor. Morgan had invested time and effort into raising cavalry, but Nelson wanted men of any sort to come as soon as possible.

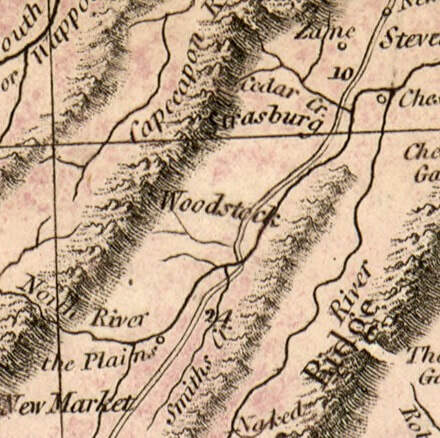

You can’t conceive how reluctantly the people leave their homes at this season of the year, and it was the general opinion if I left the Country before they were imbodied, they would not be prevailed upon to March; small parties have been pushed on and a few days, will produce the wished for march of the whole. ◊ Wheat, grown as what is now sometimes called "winter wheat," was planted in the fall and harvested in June and July. After Saratoga and especially Cowpens, Morgan was a hero. The legislature was counting on his reputation and charisma to inspire men to enlist.

Give me leave to press the forming magazines at the places mentioned in my last, from whence the army may be supplyd without delay: and I am of opinion too many workmen can not be imployd in making and repairing warlike instruments—many hands may be set at work in this part of the Country. For want of storehouses we are obliged to pick up provisions in such quantities as it can be found, this frequently subjects us to scantiness and is very disgusting to the people, both which, I humbly apprehend, may be obviated by the recommended magazines. I shall immediately march my voluntiers and what Militia are ready, the remainder will follow with the greatest dispatch. ◊ Morgan is being argumentative here. In the close of Nelson's June 20 letter to Morgan, he explicitly said they had no time for devising complex supply schemes, but indicated they might turn to Morgan's ideas later.

Had I known my presence in the Army was so immediately expected, I would have joined it on the earliest notice, but I had gone too far in the Voluntier s[c]heme to recede; it was and still is my opinion they will be extremly usefull—many of the officers I have appointed, have seen service, and the rest, Gentlemen who may be depended on.

However sanguine some Gentlemen may be in a hasty gathering of the Militia, You, Sir, who have seen service know, so well an appointed Army as the Brittish, Commanded by so experienced an officer as Lord Cornwallis, is not to be beaten but by well furnished troops, especialy with proper arms and well equipped horse. Could I have properly completed my Volunteer corps of two thousand, I flatter my self we should have done honor to our selves, and distinguished services to our Country. ◊ Morgan is apparently inoculating himself from blame, implying that if his recruits did not perform well, insufficient time to recruit, equip, and train them would be the cause. Morgan joined General Lafayette with the men he was able to raise on July 7th, the day after the Battle of Green Spring. He was unable to continue more than a few days and returned home.

I have the honor to be

Sir

Your most obedt hum Servt

26th June 1781

Danl Morgan