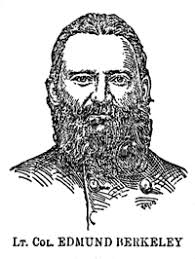

In 1905, Edmund Berkeley wrote a poem to welcome Union veterans to a reunion at the Manassas Battlefield that is notable for the grace shown to men who had fired at him on that very field. It was published by the Society of the Army of the Potomac in the report on its fortieth reunion.

O Lord of love, bless thou to-day

This meeting of the Blue and Gray.

Look down, from Heaven, upon these ones,

Their country's tried and faithful sons.

As brothers, side by side, they stand,

Owning one country and one land.

Here, half a century ago,

Our brothers' blood with ours did flow;

No scanty stream, no stinted tide,

These fields it stained from side to side,

And now to us is proved most plain,

No single drop was shed in vain;

But did its destined purpose fill

Of carrying out our Master's will,

Who did decree, troubles should cease

And his chosen land have peace;

And to achieve this glorious end

We should four years in conflict spend;

Which done the world would plainly see

Both sides had won a victory.

And then this reunited land

In the first place would ever stand

Of all the nations, far and near,

Or East or Western hemisphere.

Brothers, to-day in love we've met,

Let us all bitterness forget,

And with true love and friendship clasp

Each worthy hand in fervent grasp

And in remembrance of this day

Let one and all devoutly pray:

That when our earthly course is run

And we, our final victory won,

Together we'll pass to that blessed shore

That ne'er has heard the cannon's roar;

And where our angel comrades stand

To welcome us to Heaven's bright strand.