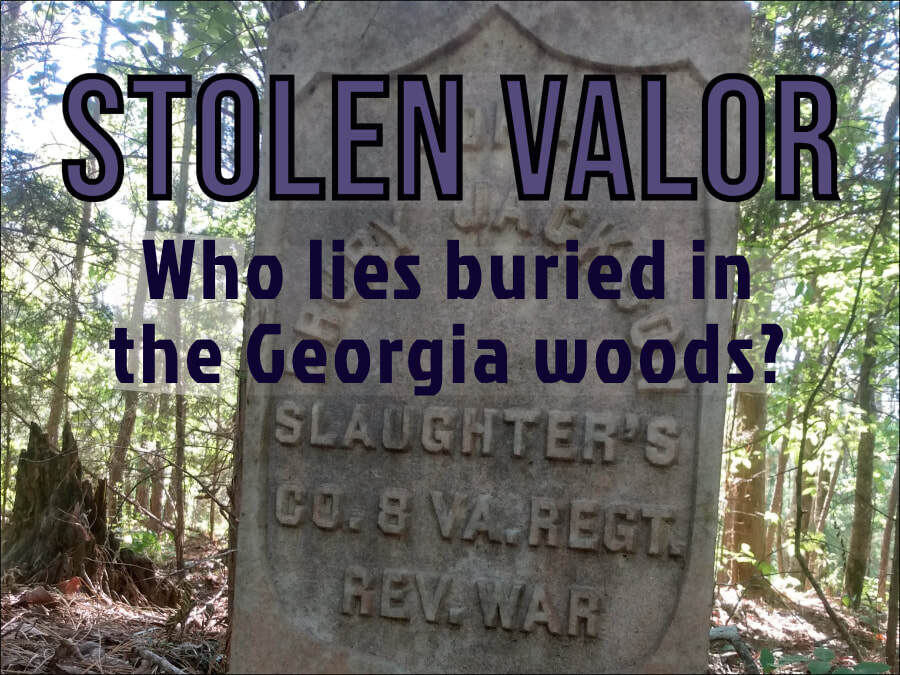

Dave Gilbert of the Simon Kenton Chapter, Kentucky SAR, after he and Stuart Martin found Private Kay's headstone lying flat under the snow. (Stuart Martin)

Private Kay's original headstone. Kay was wounded at the Battle of Brandywine. (Stuart Martin)

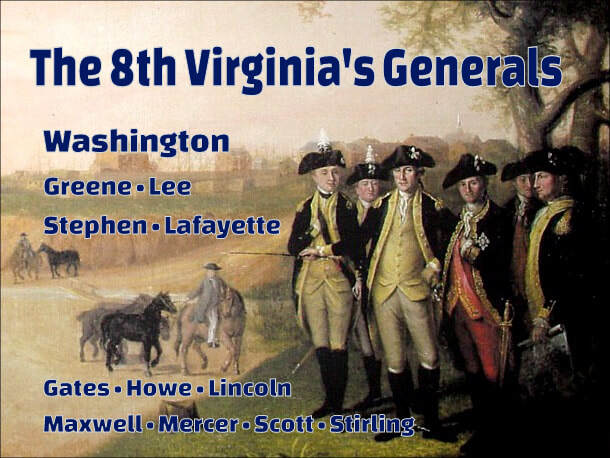

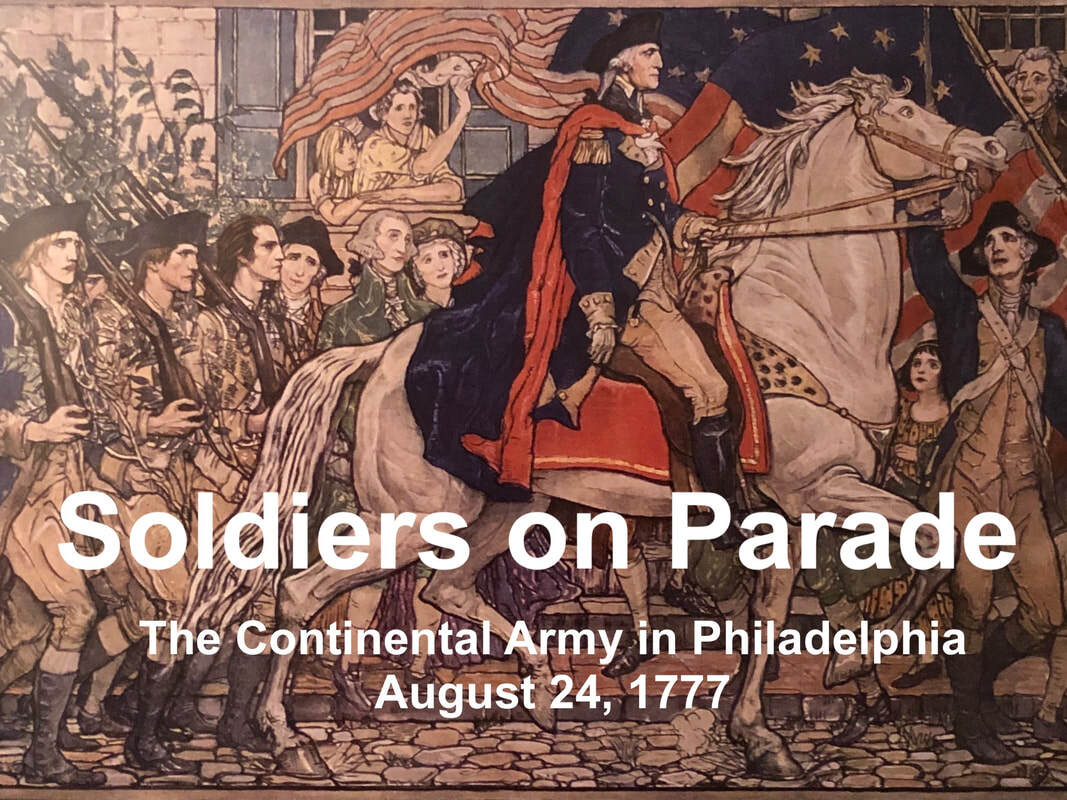

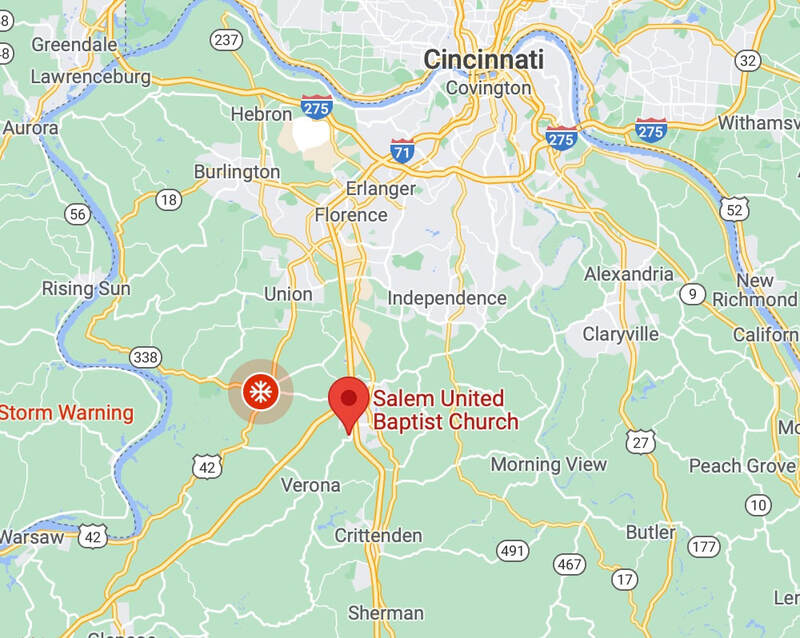

When Berry and Jolliffe were appointed by the Frederick County Committee of Safety, they had recruiting quotas to fill. It appears that Berry's ties to King George County were still so strong that he made a trip home to recruit among his old friends and neighbors. That, at any rate, would explain Kay’s enlistment. Berry’s company was assigned to the 8th Virginia Regiment, which was brought south into the Carolinas in the spring of 1776. Berry and Kay were present in Charleston for the Battle of Sullivan’s Island, though most 8th Virginia men were not in combat. We know Private Kay was at Sunbury, Georgia that summer when many of his comrades succumbed to malaria. Having grown up near the Chesapeake, he may have had some resistance to the mosquito-borne disease. The soldiers were given furloughs after returning to Virginia that winter and then marched to Philadelphia where they were inoculated for smallpox. Lieutenant Jolliffe was quarantined with smallpox that spring in Winchester, either naturally contracted or from inoculation, and died from it.)

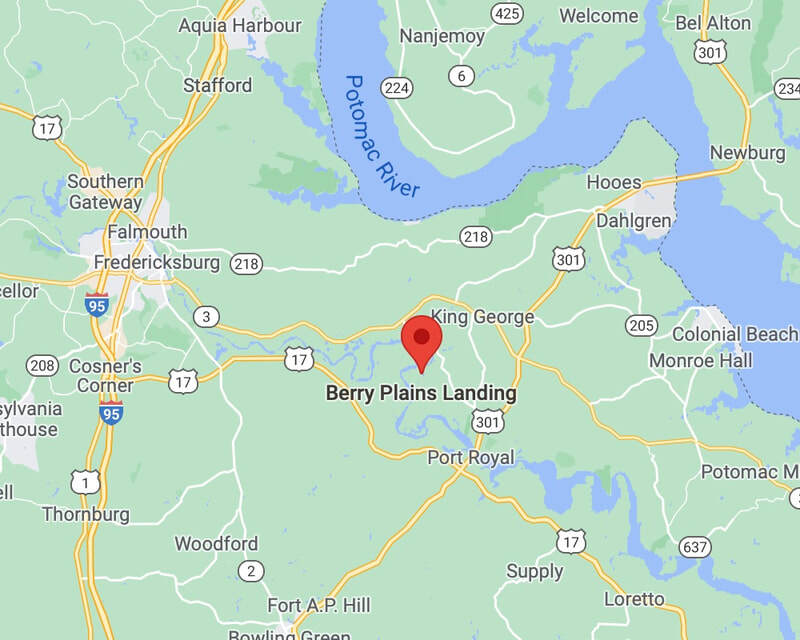

Berry Plain, built when Thomas Berry's grandfather was still alive about 1720, still stands in King George County near the Rappahannock River. This was Captain Berry's childhood home. Though now surrounded by development, it has been nicely restored and retains many of its centuries-old boxwoods.

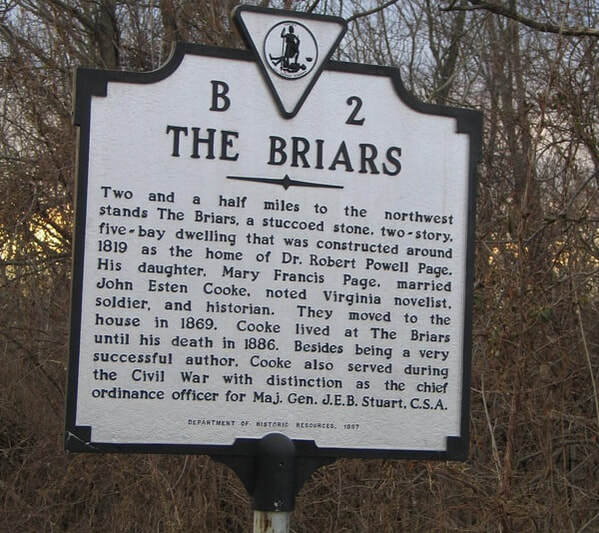

Captain Berry is believed to be buried at The Briars.

Read more: "The Stamp Act and Captain Berry"