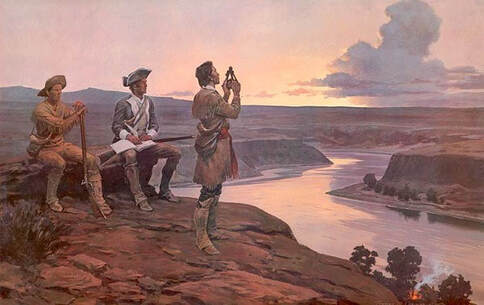

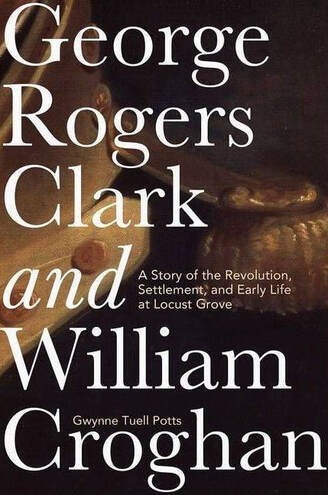

George Rogers Clark & William Croghan by Gwynne Tuell Potts (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2020)

George Rogers Clark was famous, once. He was a towering figure on the western front of the Revolutionary War. Potts quotes French Gen. Henri Victor Collot describing Clark as the person who had “gained from the natives almost the whole of that immense country which forms now the Western states.” Collot said Clark was “the rival, in short, of George Washington.” Clark’s reputation was diminished in his own lifetime and his fame has since waned. His story is not taught in most schools and his Virginia commission excludes him from the pantheon of well-known Continental generals.

...continue to The Journal of the American Revolution.