The 8th Virginia’s recruitment area was vast—covering almost the entire Virginia frontier, which at that time stretched from Pittsburgh to the Cumberland Gap—a distance of 450 miles. Those two places were, at that time, the only practical access points to the “Kentucky Country”—all of which was, at the start of the war, part of Fincastle County, Virginia. To get there, you could float down the Ohio River from Pittsburgh, or you could travel overland through the Cumberland Gap. Few had taken the latter route, however, when James Knox led a hunting party that way in 1770.

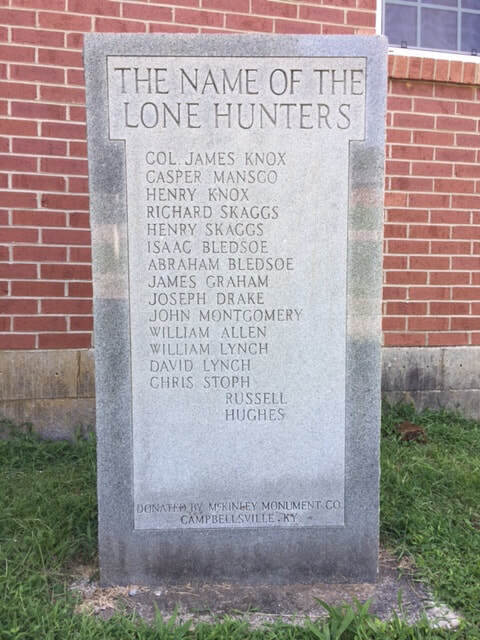

Knox was one of the original “Long Hunters,” who entered Kentucky on months-long or even years-long hunting trips, intending to return with large quantities of pelts. Daniel Boone is by far the most famous of the long hunters, but that is partly because there is only room for one of these little-remembered adventurers in public memory.

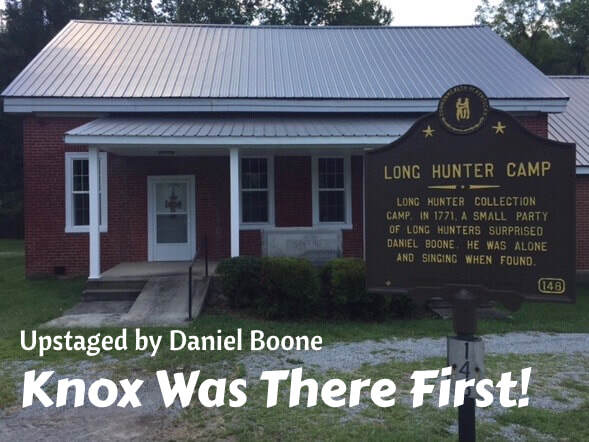

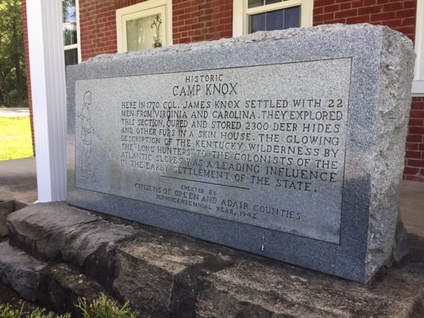

In 1770, James Knox and his team established a hunting camp and pelt repository (a “skin house”) by the north bank of a creek now known as Skinhouse Branch. Years later, a church was built on the same site. Today, the 187-year old nondenominational church sits at the intersection of Skinhouse Branch and Long Hunters Camp roads—neither of which carries enough traffic to warrant painted markings. It is surrounded by farms growing corn, tobacco, and soybeans. Two stone markers were put there long ago by local citizens to memorialize James Knox and the hunting expedition of 1770. In front of them, and closer to the road, is an official Kentucky state historic marker noting that Daniel Boone was also there—a year later.

Early in 1776, Knox recruited one of the 8th Virginia’s ten companies. His men were decimated by malaria during the South Carolina expedition of that summer and fall. By the spring of 1777, only a handful were left. Knox became a captain in Morgan’s Rifles and commanded a company at the victory at Saratoga. He took a few of his 8th Virginia men with him, and his 8th Virginia Regiment company ceased to exist. He was a prominent citizen of Kentucky in his later years, but has always been overshadowed by Daniel Boone.

Read More: "Searching for Captain Knox" (3/29/18)

The Knox monument is upstaged by a marker celebrating Daniel Boone's presence at Camp Knox a year later.

Knox's hunting companions are listed under a header that was probably intended to say "The Names of the Long Hunters."