Early orders create “buzz,” so consider buying yours now.

THE FORT PLAIN MUSEUM IS OFFERING

A GENEROUS DISCOUNT

"I fought in our Revolutionary War for liberty."

—Sgt. John Vance

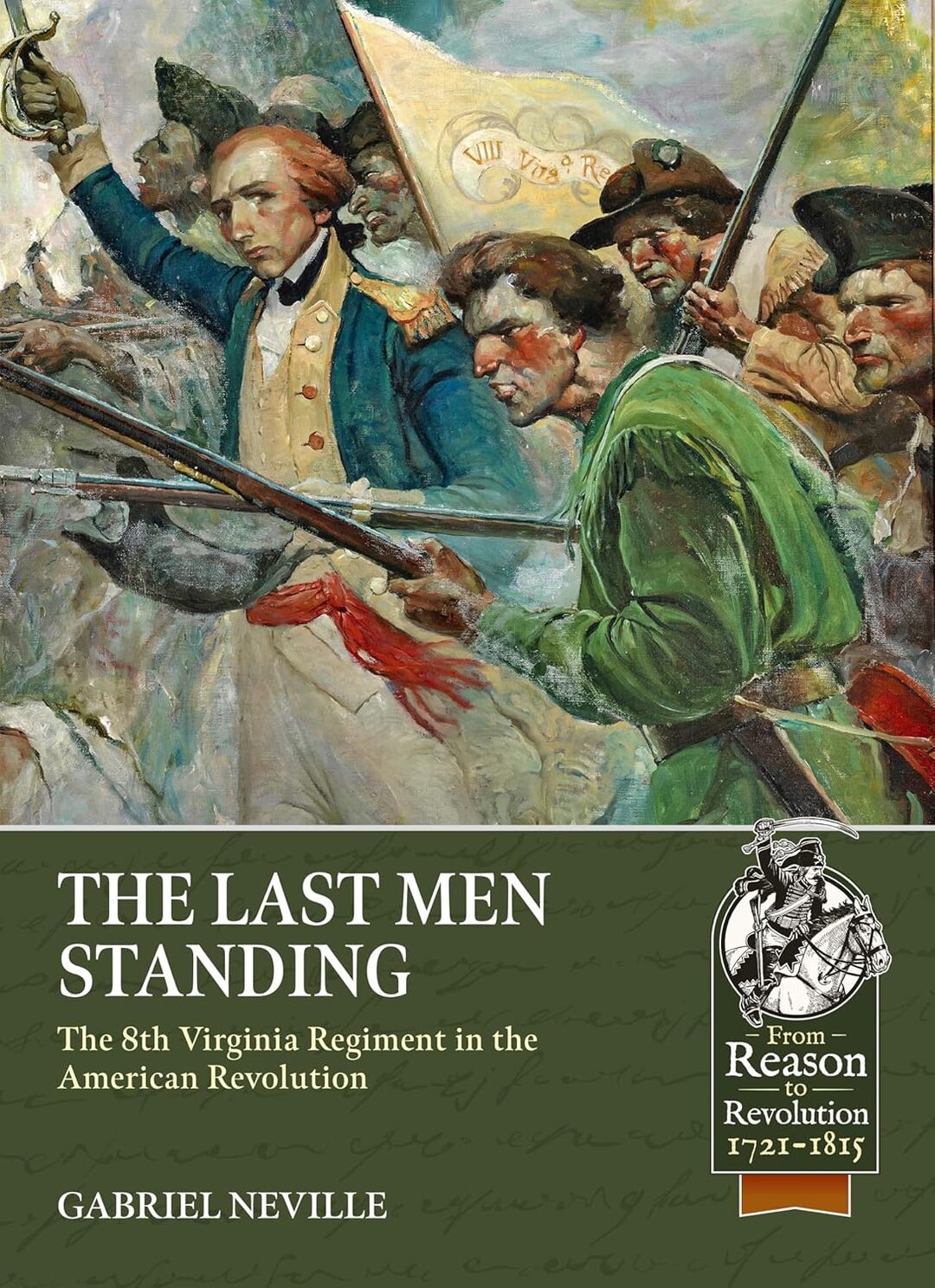

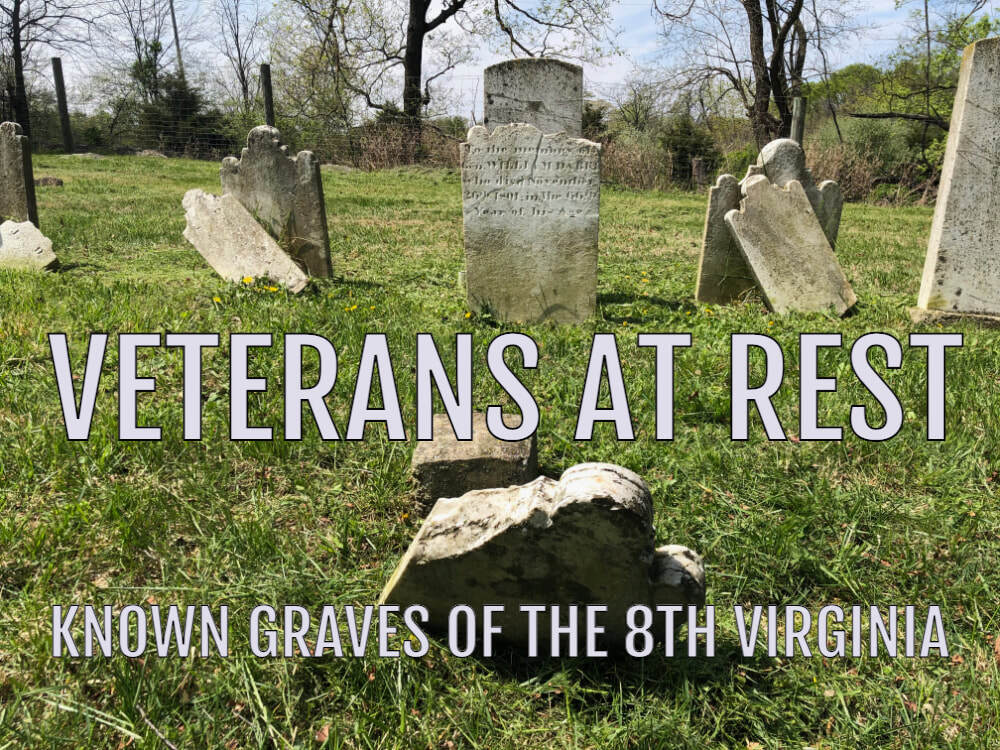

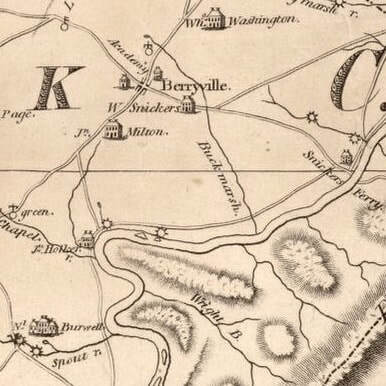

Frequently divided and detached, the regiment’s men served almost everywhere: Charleston, White Plains, Trenton, Princeton, Short Hills, Cooch's Bridge, Brandywine, Saratoga, Germantown, Valley Forge, and Monmouth. They suffered, and many died from frostbite, malaria, smallpox, malnourishment, musket balls, bayonets, and cruel imprisonment. Their numbers dwindled until only a few remained to help corner Charles Cornwallis at Yorktown. Victorious, those who survived turned west to build the America we know.

The Last Men Standing includes over a hundred color and black-and-white illustrations, twenty maps, and an appendix listing every identifiable man who served. It will be published by Helion & Company and is now available for pre-order. It is available at Amazon and other retailers, or from The Fort Plain Museum at a generous discount.

"...one of the most perfect battalions of the American Army."

—George Bancroft