8th Virginia Colonel Abraham Bowman’s frontier cabin looks better than has in 200 years.

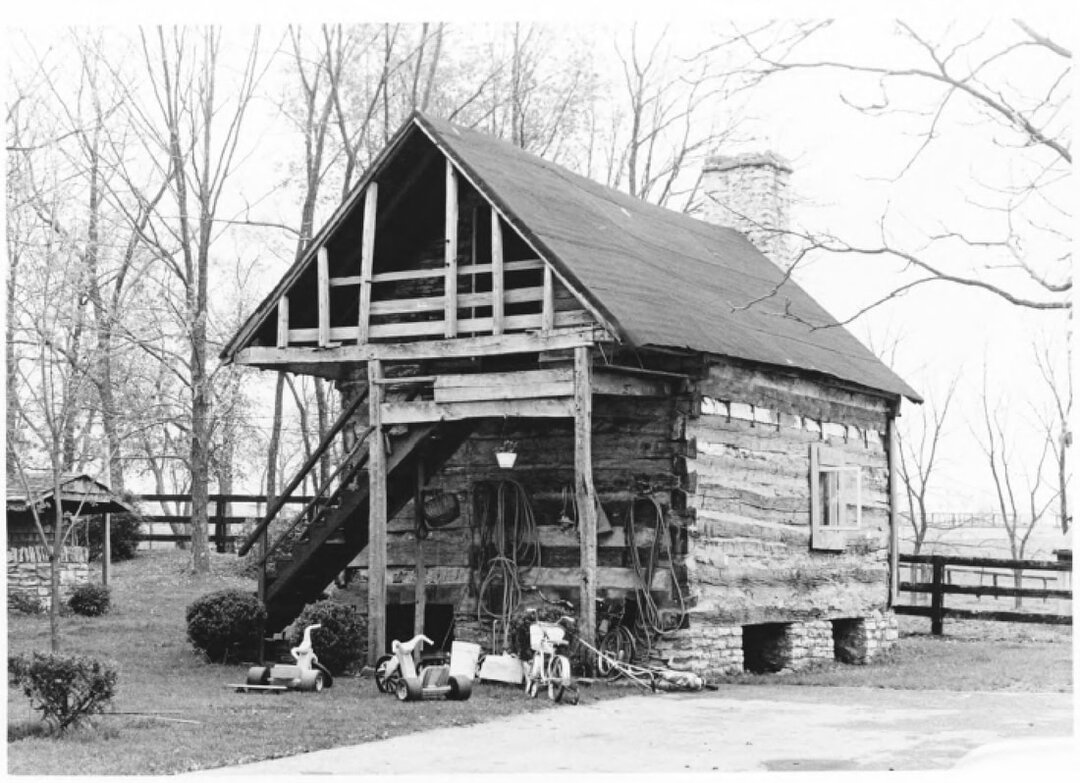

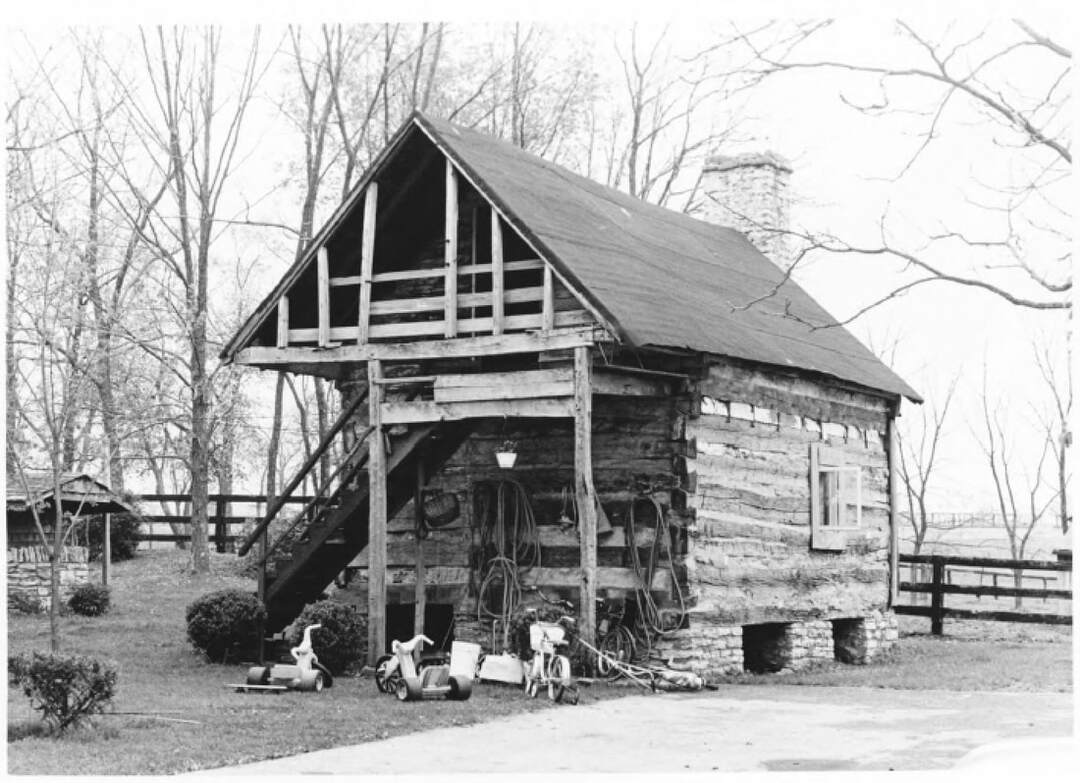

Frontier log cabins, usually built of American Chestnut on stone foundations, were very durable structures. A surprising number of them survive today, including the cabin 8th Virginia Colonel Abraham Bowman built about 1779 or 1780 when he moved to Kentucky. Nevertheless, after two centuries, the Bowman cabin showed signs of deterioration (and alteration) when images of it were submitted to the National Park Service in 1979.

Bowman and his brothers are remembered as accomplished equestrians, reportedly known back in the Shenandoah Valley as the “Four Centaurs of Cedar Creek.” Appropriately, most of his land in Kentucky is now part of one of the most important equestrian facilities in the world. His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the Emir of Dubai and Prime Minister of the United Arab Emirates, is a horse enthusiast and owner of a global thoroughbred stallion operation which stands stallions in six countries. Soon after acquiring the property in 2000, Sheikh Mohammed had the Bowman cabin repaired and restored, along with other properties built long ago for Bowman’s children.

The unique cabin, which features a basement and an exterior staircase to a second floor, has never looked better. The most notable change from the restoration is the reorientation of the exterior stairs, presumably to their original position and providing more headroom over the basement stairs.

Frontier log cabins, usually built of American Chestnut on stone foundations, were very durable structures. A surprising number of them survive today, including the cabin 8th Virginia Colonel Abraham Bowman built about 1779 or 1780 when he moved to Kentucky. Nevertheless, after two centuries, the Bowman cabin showed signs of deterioration (and alteration) when images of it were submitted to the National Park Service in 1979.

Bowman and his brothers are remembered as accomplished equestrians, reportedly known back in the Shenandoah Valley as the “Four Centaurs of Cedar Creek.” Appropriately, most of his land in Kentucky is now part of one of the most important equestrian facilities in the world. His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the Emir of Dubai and Prime Minister of the United Arab Emirates, is a horse enthusiast and owner of a global thoroughbred stallion operation which stands stallions in six countries. Soon after acquiring the property in 2000, Sheikh Mohammed had the Bowman cabin repaired and restored, along with other properties built long ago for Bowman’s children.

The unique cabin, which features a basement and an exterior staircase to a second floor, has never looked better. The most notable change from the restoration is the reorientation of the exterior stairs, presumably to their original position and providing more headroom over the basement stairs.

The Cabin circa 1979 (Courtesy of the National Park Service)

Side view of the cabin.

Rear view of the cabin.