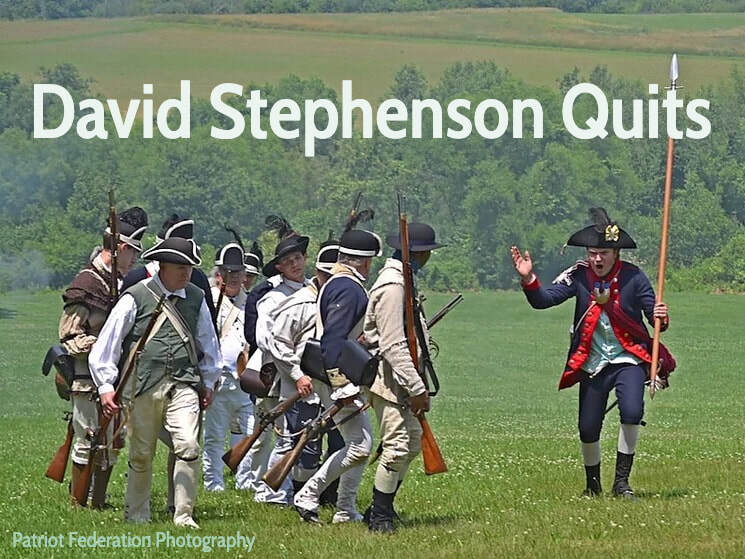

The subject of his ire was New Jersey Brig. Gen. William Maxwell, who led the temporary light infantry unit for one critical month in the fall of 1777. Maxwell’s Light Infantry is mentioned in most histories of the Philadelphia Campaign, but deserves a closer look. It played a key role in two significant engagements and performed quite well. Maxwell himself deserved criticism, though exactly how much is hard to determine now. His second in command, Indian fighter Col. William Crawford, likely deserves more recognition than he has received.

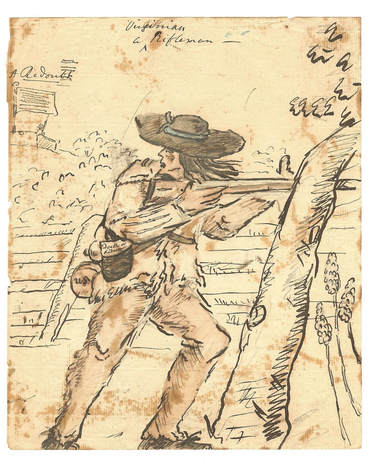

Continental Riflemen

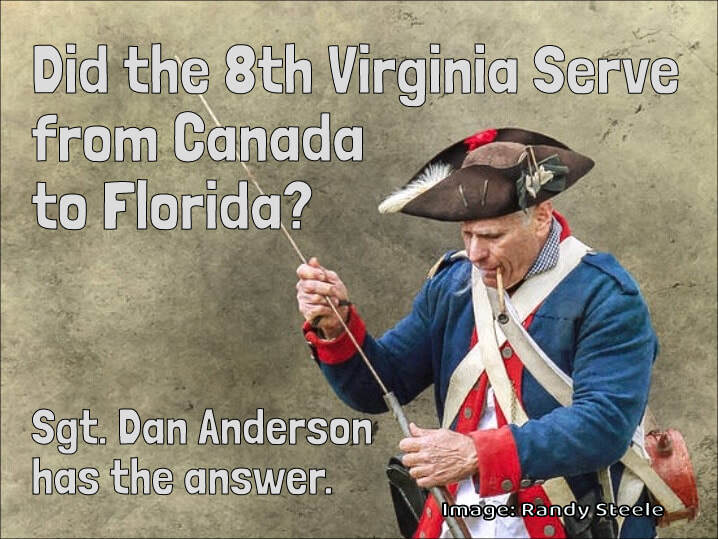

For the American army early in the war, “light infantry” usually meant “riflemen.” Though accurate at long range, rifles took longer than muskets to reload and could not carry bayonets. They were good for sniping at, harassing and delaying the enemy. However, in a traditional line of battle they were inferior weapons. In close combat, they were almost useless. Riflemen were sometimes issued spears to defend themselves from bayonet charges. They had other problems, too. Col. Peter Muhlenberg of the originally all-rifle 8th Virginia Regiment told Washington in February, “The Campaign we made to the Southward last Summer fully convinces me, that on a march where Soldiers are without Tents, & their Arms continually exposd to the Weather; Rifles are of little use.”

...continue to the The Journal of the American Revolution.