A 2015 photograph shows the Craig Cemetery in deplorable condition. (Jon Craig, Find-a-Grave)

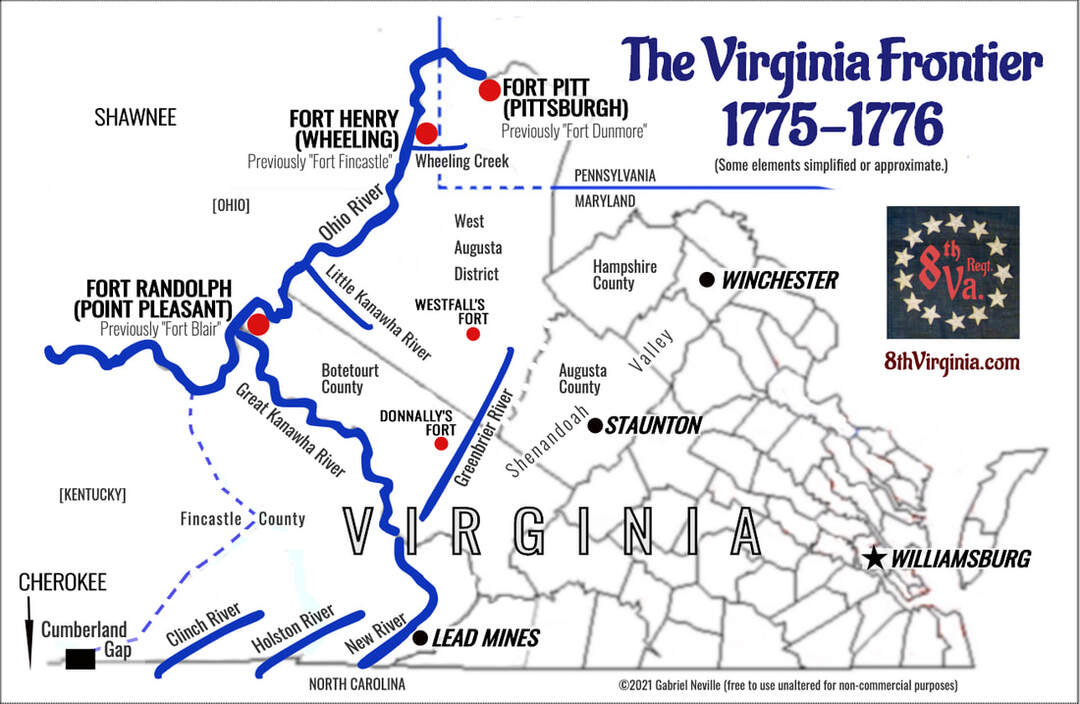

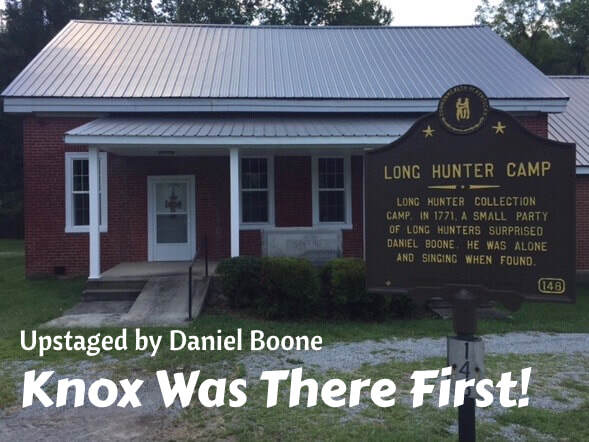

Even before there were any Virginia Continental regiments, Craig signed on to help lead one of the Old Dominion’s independent frontier companies. He was a lieutenant under Capt. William Russell in a company that ranged the southwest Virginia frontier from 1775 to 1776. In 1776 he joined Capt. James Knox in forming a Fincastle County company assigned to the 8th Virginia Regiment. After a year serving in the south, he and Knox were selected to lead a company in Daniel Morgan’s elite rifle battalion. With Morgan and Knox, he played a key role in the defeat of Gen. John Burgoyne at Saratoga—the first major American victory and the event that persuaded the French to openly support the cause.

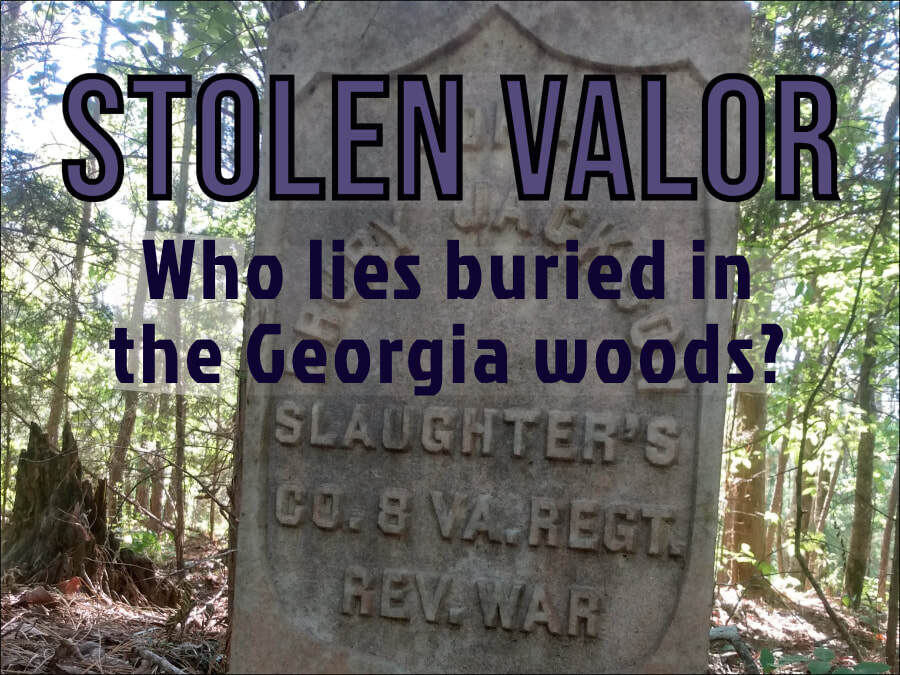

An undated image, evidently clipped from a newspaper, shows Craig's headstone upright and intact. (Liz Gossett, Find-a-Grave)

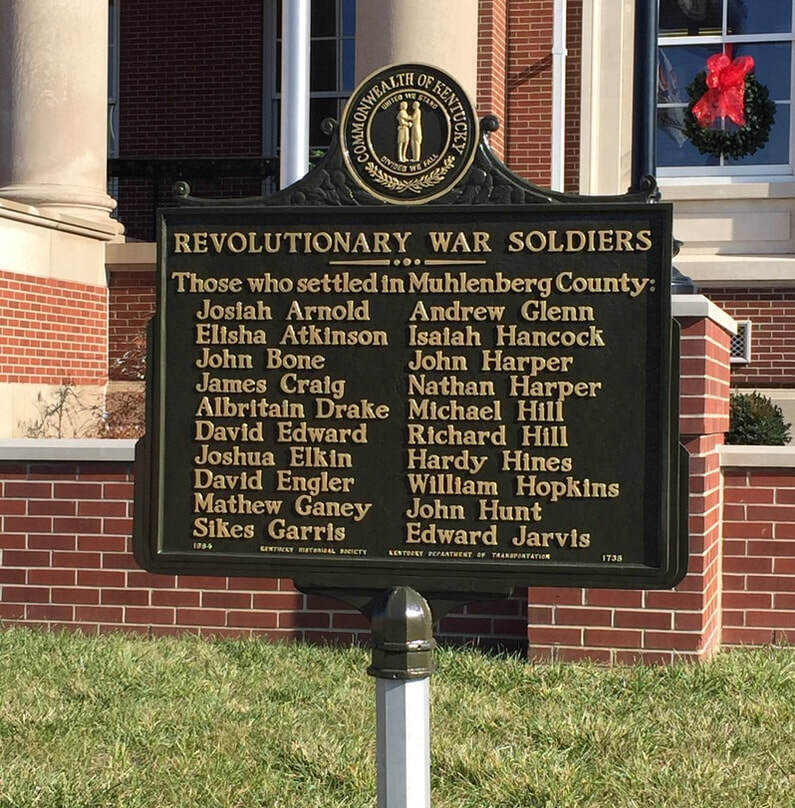

Craig is listed on a state historical marker in front of the Muhlenberg County court house. Josiah Arnold is also an 8th Va. veteran. (E. C. Russell Chapter, DAR)

An old photograph shows the cemetery in good condition. It was maintained by Luther Craig until he died in 1960. (Courtesy Liz Gossett, Find-a-Grave)

A 2004 photograph shows fallen headstones and unrestrained weeds, 44 years after maintenance ceased. (Liz Gossett, Find-a-Grave)