The cemetery in Sunbury, Georgia. The 8th Virginia was overwhelmed by malaria in the summer of 1776 and a great many of them died here. There are no markers or monuments for them. (Author)

The 8th Virginia saw hard service. It is hard to imagine that the mostly young men who first signed up in the winter of 1775-1776 had any idea what was really in store for them. All of the numbers above add up to about 240 men. Another 90 deserted--many of them when the still technically Provincial regiment was taken out of the province by Maj. Gen. Charles Lee in May of 1776. When the terms of the regiment's original two-year men neared their ends as the snow melted at Valley Forge there were only about fifty of them left. Heroes to be sure. Like all war survivors, though, they would no doubt have ascribed greater heroism to their fallen comrades.

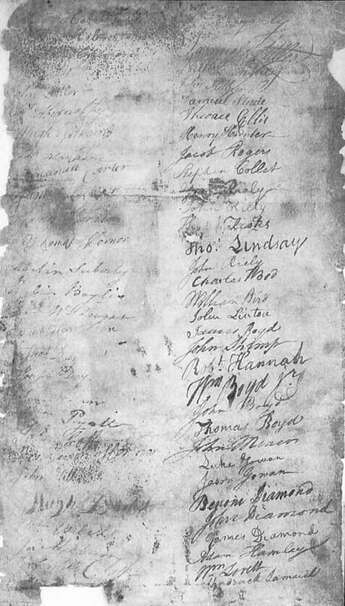

Listed below are the names of the 121 men known to have died while in service.

Because new enlistees came on board at various times during the regiment's existence, calculating precise casualty statistics is complicated. Nearly all (but not all) of the events connected with data below occurred during the 2-year original enlistment period. There are no records for Capt. John Stephenson's one-year company. Captain Knox's company was not fully recruited. Percentages are based on nine theoretically full companies and assume all men are original enlistees. Percentages should therefore be taken as estimates and may be refined in the future.

1% wounded/discharged (6)

5% captured (35)

14% deserted (85)

20% died (120)

21.5% sick/discharged early (132)

48% casualty rate (no desertions)

62% total attrition rate

1st Lieut. John Jolliffe, April 6, 1777

Ens. William Mead, Nov. 20, 1776

Sgt. Reese Bowen, Sept. 6, 1776

Pvt. William Buckley, Sept. 16, 1776

Pvt. Hugh Burns, Oct. 21, 1776

Pvt. Jesse Chamblin, Oct. 31, 1776

Pvt. Peter Fletcher, Nov. 10, 1776

Pvt. Thomas Hankins, Nov. 29, 1776

Pvt. Joseph Hickman, May 18, 1777

Pvt. Luke Hines, Nov. 10, 1776

Pvt. Dennis Kingore, Sept. 8, 1776

Pvt. Neil McDade, Nov. 25, 1776

Pvt. Thomas McVay, Oct. 1, 1776

Pvt. Louis Routt, Nov. 10, 1776

Pvt. Garett Trotter, Oct. 19, 1776

Pvt. Peter Vandevourt, Dec. 31, 1776

Capt. Richard Campbell's Company:

Lt. Col. Richard Campbell, Sept. 8, 1781 (Eutaw Springs)

Sgt. John Bowman, Aug. 19, 1779

Pvt. William Davis, Sept. or Oct., 1777 (Brandywine or Germantown)

Pvt. Frederick Long, Sept. or Oct., 1777 (Brandywine or Germantown)

Capt. Jonathan Clark's Company

Sgt. Maj. John Hoy, Dec. 3, 1776

Sgt. George Parrott, Nov. 6, 1776

Sgt. Humphrey Price, Nov. 24, 1776

Cpl. William Brown, March 30, 1777

Cpl. Mathew Toomey, Dec. 20, 1776

Pvt. Nicholas Bowder, June 13, 1776

Pvt. Nathan Brittain, Oct 17, 1776

Pvt. Thomas Brittain, Sept. 29, 1776

Pvt. Isaac Dent, Nov. 3, 1776

Pvt. Mathias Funk, Dec. 20, 1776

Pvt. Martin Honey, Sept. 20, 1776

Pvt. John Maxwell, Dec. 25, 1776

Pvt. Henry Moore, Sept. or Oct., 1777 (Brandywine or Germantown)

Pvt. Isaac Pemberton, Jan. 12, 1778

Pvt. Meredith Price, Jan. 3, 1777

Pvt. Simon Siron, unknown date (left in Georgia)

Pvt. Michael Wall, unknown date (before June 13, 1777)

Pt. Walter Warner, Oct. 4, 1776

Capt. William Croghan's Company

Sgt. John McDoran, Jan. 30, 1777

Cpl. Michael Kelly, Sept. 11, 1777 (Brandywine)

Cpl. William Penny, before May 18, 1777

Cpl. James Tucker, Dec. 27, 1776

Drummer Francis Prush, before May 18, 1777

Fifer Gabriel Christy, before April 1777

Pvt. John Brock, March 18 or 25, 1776

Pvt. John Brown, before April 1777

Pvt. William Cochran, before April 1777

Pvt. Robert Cochran, Sept. 1776

Pvt. Philip Cole, Jan. 30, 1777

Pvt. John Donnally, April 14, 1777

Pvt. Nicholas Doran, April 13, 1777

Pvt. William Gaddis March 15, 1777

Pvt. Patrick Garry, Nov. 11, 1776

Pvt. Joseph Gonsley, Feb. 1777

Pvt. William Goodman, before April 1777

Pvt. James Gorwin, Feb. 8, 1777

Pvt. Patrick Hall, ca. Jan. 1, 1777

Pvt. David Hanson, before April 1777

Pvt. Lewis Henry, Nov. 1776

Pvt. John Hinds, Aug. 14, 1776

Pvt. Nathaniel Hosier, before April 1777

Pvt. John James, ca. March 1, 1777

Pvt. Jesse Job, before April 1777

Pvt. Able Levesque, March 17, 1777

Pvt. George Martin, Feb. 1777

Pvt. Michael Martin, Feb. 1777

Pvt. Moses Martin, Feb. 1777

Pvt. Thomas Owens, Sept. 11, 1777 (Brandywine)

Pvt. Thomas Ryan, before May 18, 1777

Pvt. Henry Saltsman, Oct. 4, 1777 (Germantown)

Pvt. James Smyth, Oct. 19, 1776

Pvt. John Tuck, before April 1777

Pvt. Daniel Viers, March 3, 1777

Capt. William Darke's Company

Pvt. Daniel Cameron, Jan. 15, 1777

Pvt. WilliamEngle, ca. March 1776

Pvt. Jonathan Herrin, Dec. 1776

Pvt. Jeremiah Humphreys, Oct. 27, 1776

Pvt. George Ketcher, Oct. 24, 1776

Pvt. William Pingle, Dec. 1, 1776

Pvt. John Polson, Oct. 26, 1776

Pvt. George Pritty, Dec. 1, 1776

Pvt. George Smith, Oct. 11, 1776

Pvt. Samuel Watson, Dec. 8, 1776

Captain Robert Higgins' Company

Pvt. Zachariah DeLong, Feb. 1778 (POW)

Capt. James Knox's Company

Pvt. James Carr, Nov. 20, 1776

Pvt. Charles Carter, Dec. 24, 1776

Pvt. John Vance, Sept. 16, 1776

Pvt. Henry Wallis, Dec. 1776

Pvt. John Wilson, Nov. 8, 1776

Capt. George Slaughter's Company

Lt. Philip Huffman, March 15, 1781 (Guilford Courthouse)

Sgt. James Newman, in Georgia, 1776

Cpl. Barnett McGinnis, Nov. 25, 1776

Cpl. Cornelius Mershon, Aug 4, 1776

Fifer Henry Clatterbuck, July or Aug. 1776

Pvt. Thomas Abbett, before Feb. 3, 1777

Pvt. William Abbett, before Feb. 3, 1777

Pvt. Edward Abbott, Oct. 19, 1776

Pvt. John Abbott, Oct. 29, 1776

Pvt. William Cabbage, Nov. 24, 1776

Pvt. William Corbin, Dec. 10, 1776

Pvt. Abraham Field, Aug. 6, 1776

Pvt. Bozel Freeman, Nov. 15, 1776

Pvt. Reuben Hollaway, Aug. 3, 1776

Pvt. Utey Jackson, Aug. 20, 1776

Pvt. John Jinkins, Jan. 13 or 15, 1777

Pvt. Joseph Jones, May 6, 1777

Pvt. Edward Kennedy, Dec. 3, 1776

Pvt. Thomas Newman, in Georgia, 1776

Captain David Stephenson

No fatalities recorded.

Captain John Stephenson

No data available.

Capt. Abel Westfall's Company

Fifer Patrick Callihan, Sept. 25, 1776

Pvt. Joseph Edwards, June 13, 1776

Pvt. James Galloway, Jan. 1777

Pvt. John Haggen, March 15, 1778

Pvt. John Huff, Sept. 15, 1776

Pvt. Moses Johns, May 20, 1778

Pvt. William Kynets, Sept. 26, 1776

Pvt. Hugh Lewis, Oct. 16, 1776

Pvt. William McCormick, Dec. 28, 1776

Pvt. Zachariah Pigman, Feb. 1778 (POW)

Pvt. Philip Sanders, March 9, 1777