All ten companies of the 8th Virginia hadn’t even arrived yet when Maj. Gen. Charles Lee took the regiment south to face the enemy. Suffolk, Virginia was the designated place of rendezvous. The ten companies came from all but one of the counties along Virginia’s 350-mile frontier, stretching from the Cumberland Gap to Pittsburgh. They traveled to the rendezvous on foot, stopping in Williamsburg to collect company officers’ commissions. Col. Peter Muhlenberg and the early-arrived companies were posted at Kemp’s Landing, near Norfolk.

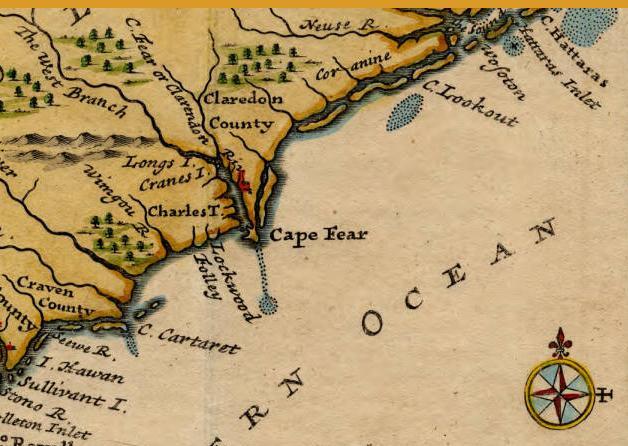

British Gen. Henry Clinton was sailing south with a significant force to meet with Gen. Charles Cornwallis, who was sailing from Britain with a fleet of warships and still more men. North Carolina was their target and a Tory uprising was their goal. On May 11, Lee impatiently wrote to the post commander at Kemp’s landing, inquiring, “[H]ave you order’d Muhlenberg’s Regiment to march to Halifax? I hope to God you have, for no time is to be lost, as we have certain news of the Enemy’s arrival in the River Cape Fear.”

British Gen. Henry Clinton was sailing south with a significant force to meet with Gen. Charles Cornwallis, who was sailing from Britain with a fleet of warships and still more men. North Carolina was their target and a Tory uprising was their goal. On May 11, Lee impatiently wrote to the post commander at Kemp’s landing, inquiring, “[H]ave you order’d Muhlenberg’s Regiment to march to Halifax? I hope to God you have, for no time is to be lost, as we have certain news of the Enemy’s arrival in the River Cape Fear.”

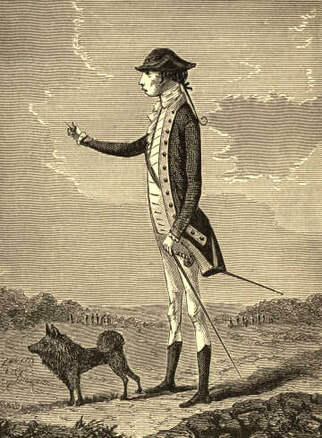

Maj. Gen. Charles Lee was a veteran (former) British officer and junior only to George Washington in the Continental army. He was a strange and notably ugly man. He lost both his career and his mind before dying of natural causes in 1782.

This was evidently true despite the absence of two complete companies. Lee may have extrapolated to account for the absent companies. Alternately, at least one of the present companies (Captain Jonathan Clark’s) appears to have enlisted numbers beyond its quota. When Muhlenberg set off on May 13, Capt. James Knox’s southwest (Fincastle County) company had not yet arrived. It was close, though—probably at Williamsburg. Or perhaps it had just arrived and needed to rest. Lee wrote, “Capt[ai]n Knox will follow the Regiment, so the Colonel must not wait for him.” Capt. William Croghan’s Pittsburgh (West August District) company, however, was even farther behind. Lee took the regiment anyway. There was no time to spare. Consequently, it would be an entire year until Croghan’s men joined the regiment.

Lee wrote to John Hancock, “As the Enemy’s advanced Guard…is actually arrived—I must, I cannot avoid detaching the strongest Battalion we have to [North Carolina’s] assistance; but I own, I tremble at the same time, at the thoughts of stripping this Province of any part of its inadequate force.” Battalions and regiments were essentially synonymous at this time. Lee was, in fact, calling the 8th Virginia the “strongest” of the province’s nine regiments. He would later confirm this assessment when he wrote to Muhlenberg, “You were ordered not because I was better acquainted with your Regiment than the rest--but because you were the most compleat, the best arm’d, and in all respects the best furnish’d for service.” To Congress he reported, “Muhlenberg’ s regiment wanted only forty at most. It was the strength and good condition of the regiment that induced me to order it out of its own Province in preference to any other.”

Lee wrote to John Hancock, “As the Enemy’s advanced Guard…is actually arrived—I must, I cannot avoid detaching the strongest Battalion we have to [North Carolina’s] assistance; but I own, I tremble at the same time, at the thoughts of stripping this Province of any part of its inadequate force.” Battalions and regiments were essentially synonymous at this time. Lee was, in fact, calling the 8th Virginia the “strongest” of the province’s nine regiments. He would later confirm this assessment when he wrote to Muhlenberg, “You were ordered not because I was better acquainted with your Regiment than the rest--but because you were the most compleat, the best arm’d, and in all respects the best furnish’d for service.” To Congress he reported, “Muhlenberg’ s regiment wanted only forty at most. It was the strength and good condition of the regiment that induced me to order it out of its own Province in preference to any other.”

Cape Fear, North Carolina, was the expected point of invasion, but the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge had quelled Loyalist support in the area.

The other nine companies marched for Cape Fear via Halifax, North Carolina, joined by a North Carolina Regiment that had come north to Virginia’s aid. Unlike every other Virginia regiment, the 8th Virginia men all carried rifles. No muskets also meant no bayonets, which were—at the end of the day—often the real implements of war. Lee compensated for this by issuing pikes (he called them “spears”) to some of the men. “I have formed two companies of grenadiers to each regiment; and with spears of thirteen feet long, their rifles (for they are all riflemen) slung over their shoulders, their appearance is formidable, and the men are conciliated to the weapon.”

Meanwhile, the British commanders were learning that the Patriot victory at Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge had quelled their hoped-for Tory uprising. They opted, therefore, for an alternate target. Just as the 8th Virginia arrived at Cape Fear, the enemy was sailing off for Charleston, South Carolina. Muhlenberg’s men continued the chase, now at a forced-march pace. A very difficult and deadly summer lay ahead of them.