Virginia was described as the the "most English" of the colonies. It had been consistently loyal to the Crown, even during the era of Parliamentary rule under Oliver Cromwell. The Church of England was integrated into the local government.

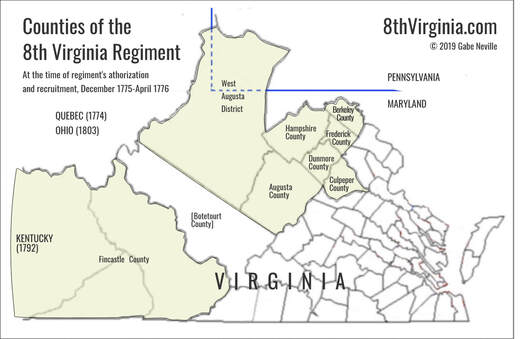

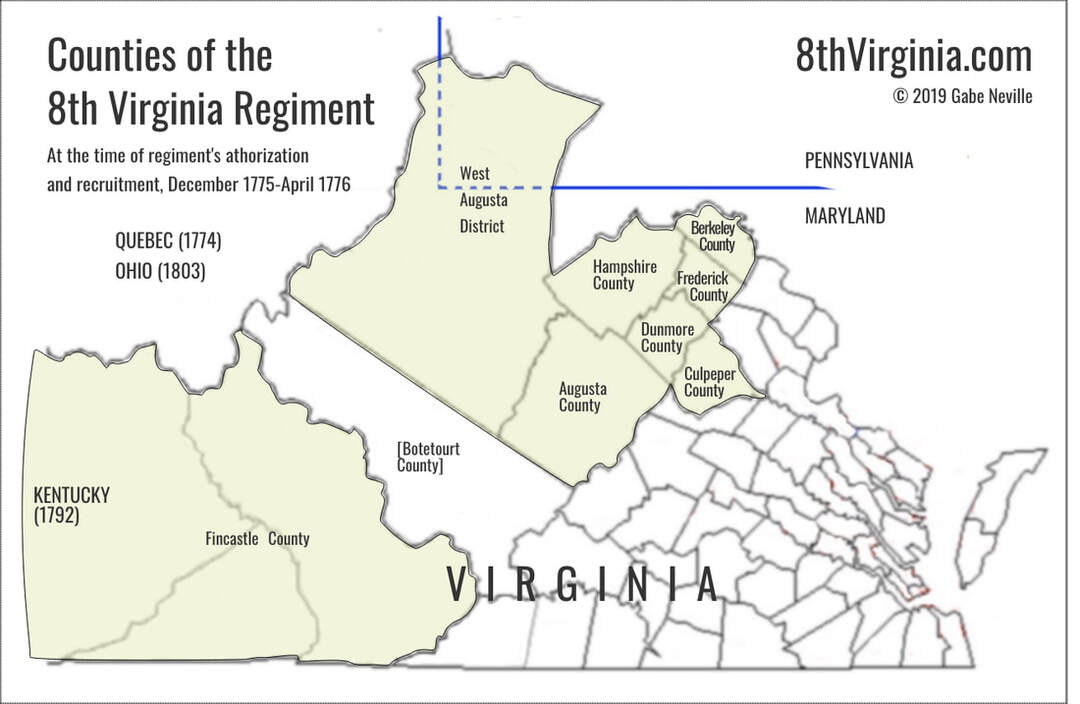

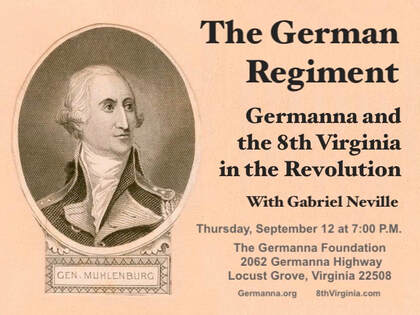

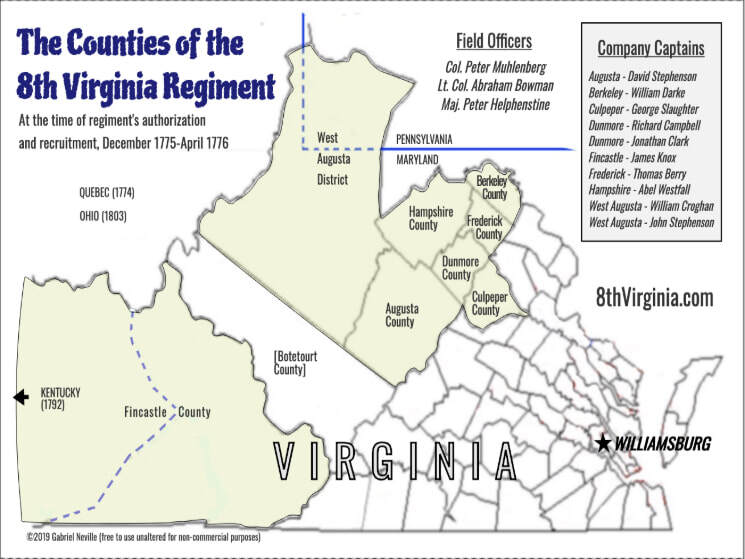

Virginia's frontier territories were different. When the Revolutionary War started, the Virginia Conventioned designated the 8th Virginia to be a "German" regiment. Thousands of Pennsylvania Germans had settled in the Shenandoah Valley. But how German was it really? There were also many Protestant Irish ("Scotch-Irish") and English settlers in the area, and the actual recruitment territory stretched all the way to Pittsburgh.

On September 12, Gabe Neville spoke at Virginia's Germanna Foundation to explore the question: "Just how German was the regiment in reality?"

Virginia's frontier territories were different. When the Revolutionary War started, the Virginia Conventioned designated the 8th Virginia to be a "German" regiment. Thousands of Pennsylvania Germans had settled in the Shenandoah Valley. But how German was it really? There were also many Protestant Irish ("Scotch-Irish") and English settlers in the area, and the actual recruitment territory stretched all the way to Pittsburgh.

On September 12, Gabe Neville spoke at Virginia's Germanna Foundation to explore the question: "Just how German was the regiment in reality?"

Learn more at the Germanna Foundation website.