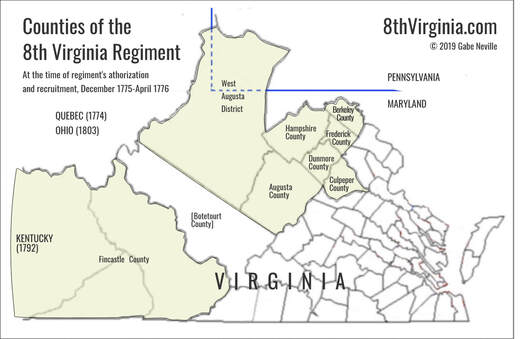

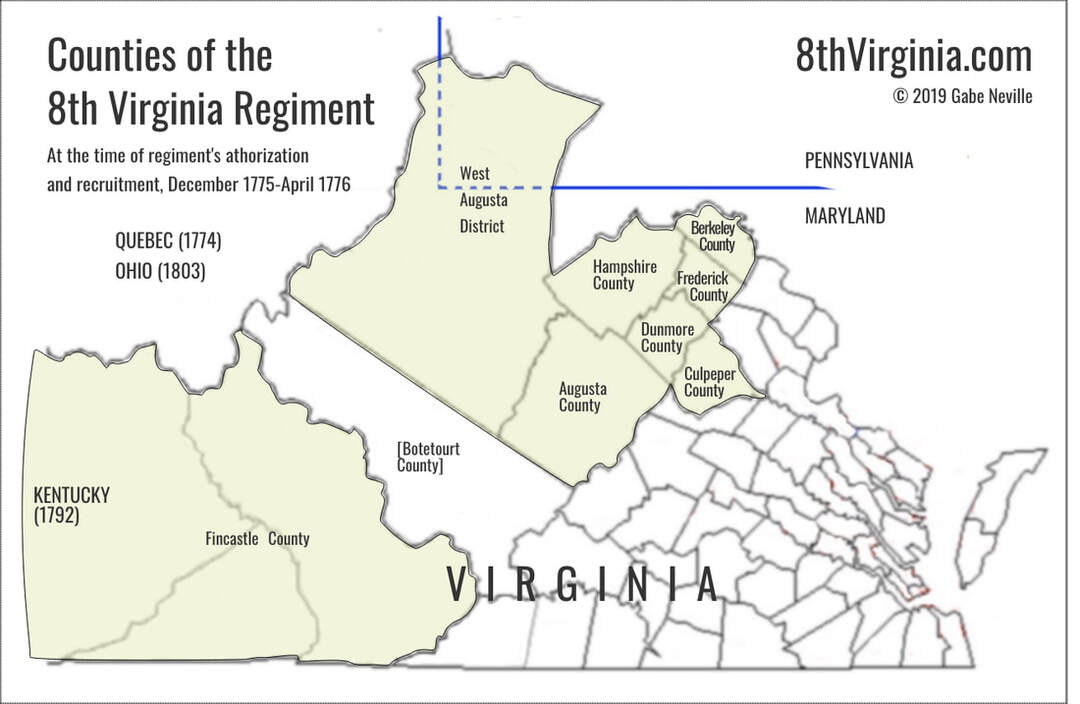

The concept may have originated with the Rev. Peter Muhlenberg and Jonathan Clark, both delegates from Dunmore County in the Shenandoah Valley. Dunmore (now called Shenandoah County) was the cultural hub of German life in the Valley. It is inconceivable that the resolution could have been drafted without the involvement of at least Muhlenberg and probably of Clark as well. Muhlenberg was the Rector of Beckford Parish, the geography of which was identical to that of Dunmore County. His church was at Woodstock, the county seat. He was, however, more than just the community’s pastor. He was the son of the patriarch or the Lutheran Church in America, whose church was in the village of Trappe near Philadelphia. Clark was the county’s deputy clerk, an important job, under Thomas Marshall (soon to be colonel of the 3rd Virginia Regiment and father of future Chief Justice John Marshall).

The Shenandoah Valley’s Germans had nearly all come the way Muhlenberg had: down the Great Philadelphia Wagon Road to Virginia. The road passed through communities that remain heavily German to this day, such as Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Scotch-Irish immigrants followed the same route, but tended to settle farther south in the Valley, around Staunton and Augusta County.

Lutheran Germans like Muhlenberg were seen by the Virginia gentry as reasonably reliable and trustworthy. Their theology differed little from the Church of England. Muhlenberg had, in fact, gone to London to be ordained before taking his position in Woodstock. (King George III was himself of German descent and his great grandfather, George I, couldn’t speak English when he took the throne.) The Ulster Irish, however, were less trusted. They were theological dissenters and often politically radical. Their Calvinist faith differed in important ways from Anglicanism. They could, however, be counted on to fight

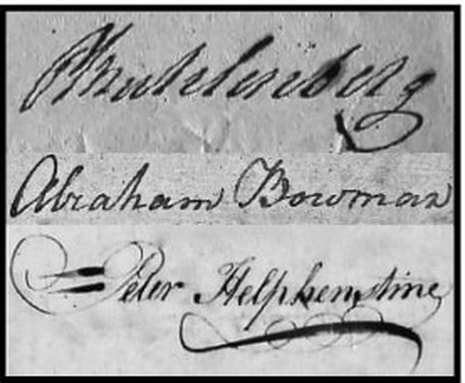

The lichen-encrusted grave of Abraham Bowman in Lexington, Kentucky. No portraits of Bowman or Helphenstine survive. Though Helphenstine is known to be buried in the Lutheran section of Winchester's Mount Hebron Cemetery, there's no surviving marker. It may be that his destitute widow was not able to afford a stone memorial. (author)

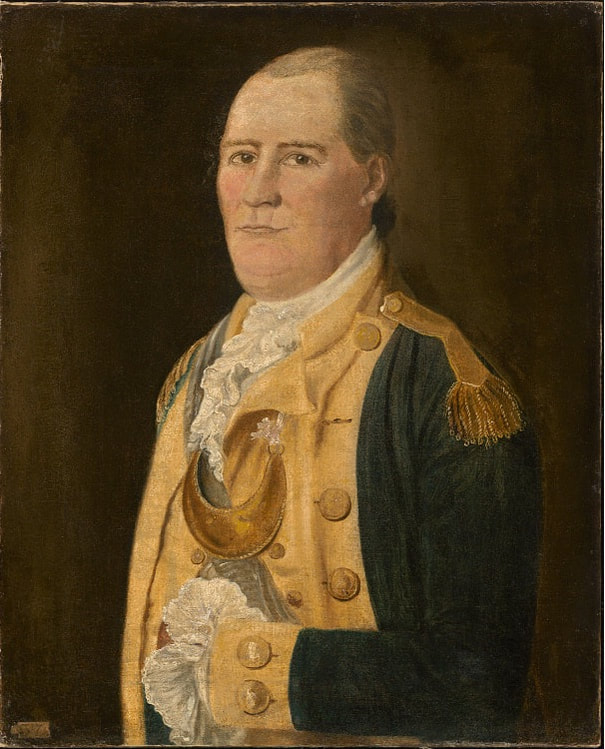

Peter Muhlenberg portrayed at the end of the war as a brevet Major General.

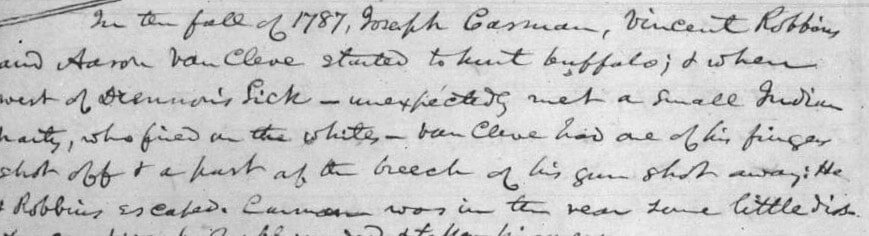

When they received their commissions Muhlenberg was twenty-nine years old and Bowman was twenty-six. The regiment’s major was Peter Helphenstine, a German from Winchester in Frederick County. He was about twice Bowman’s age, in his middle fifties. He had commanded a company in the governor’s division during Lord Dunmore’s War in 1774. He was a respected tradesman and an active Lutheran.

`

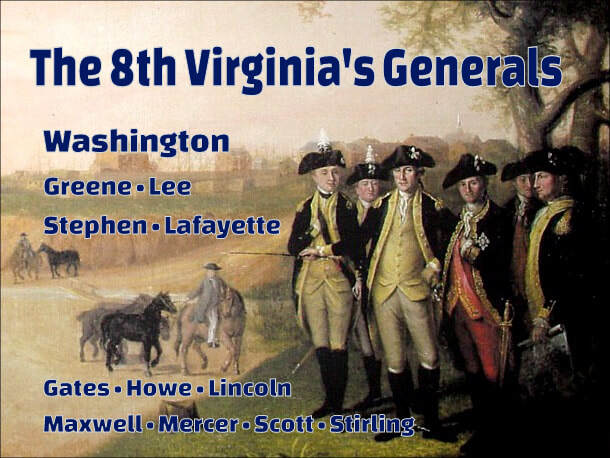

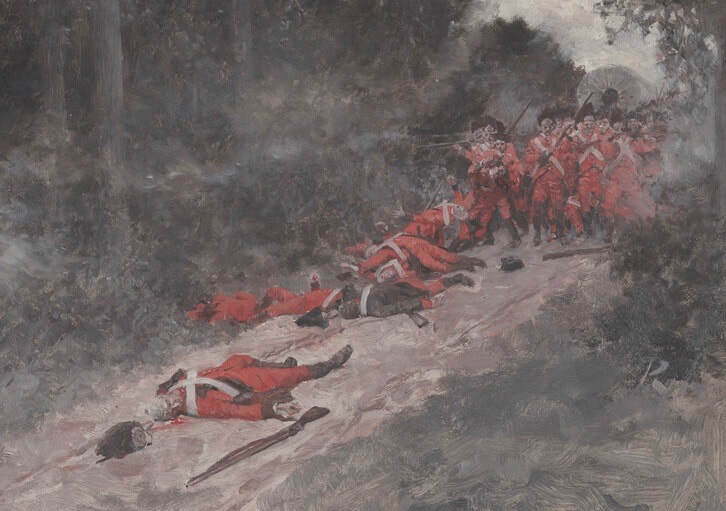

The diversity of the officers reflected the diversity in the rank and file. The 8th Virginia was a microcosm of the Continental Army at large. It was America’s original “melting pot.” Originally divided by race and religion, their shared hardships would soon make them a band of brothers.

The committees were generally dominated by English elites and could be counted on to appoint the right kind of company officers. Only two of ten companies had Irish captains: Fincastle County and the West Augusta district (both on the frontier) selected James Knox and William Croghan. Both were capable and loyal officers.

The choice of field officers, however, was up to the Virginia Convention and it chose three Germans as it had planned. Each was from a different down in the lower (northern) Shenandoah Valley. Muhlenberg was appointed to be the colonel. Abraham Bowman of Strasburg (also in Dunmore County) was appointed to be the lieutenant colonel. Bowman came from a prominent family. His grandfather, Jost Hite, had led the first group of German settlers into the valley from Pennsylvania in 1731.

More from The 8th Virginia Regiment