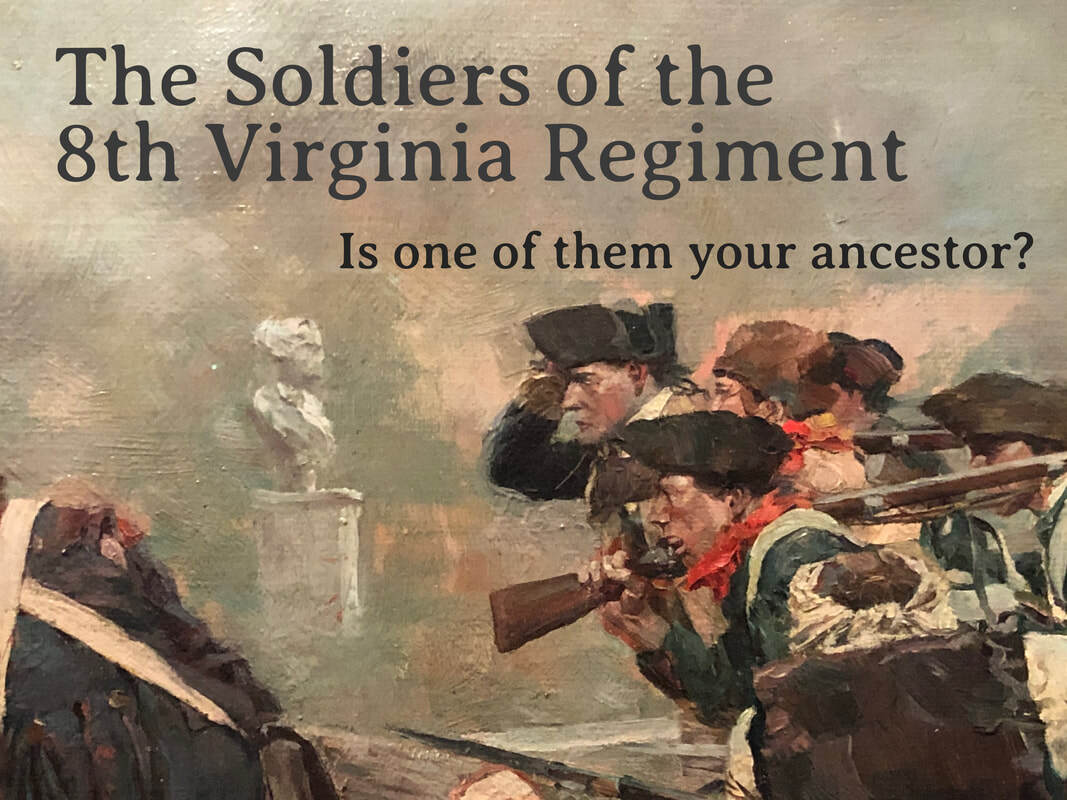

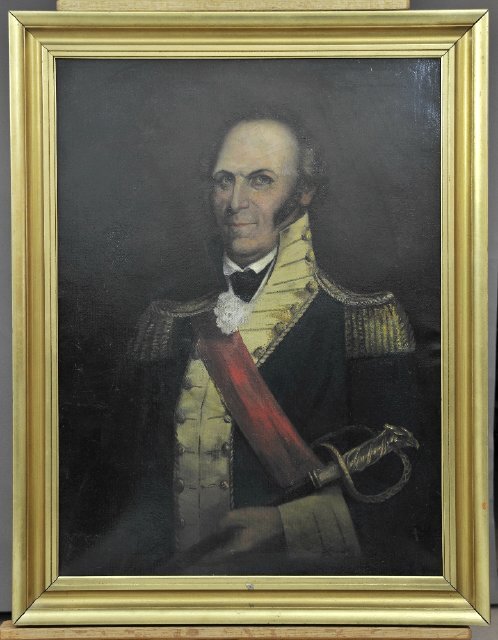

Col. Charles Scott, depicted here many years later, commanded the Virginia troops at the Battle of Drake's Farm on February 1, 1777. His bold leadership there contrasted sharply with that of Connecticut Col. Andrew Ward, who did not or could not get his troops to engage. Scott was promoted soon after to brigadier general. The 8th Virginia served in his brigade at the battles of Brandywine and Germantown. He later served as governor of Kentucky. (Kentucky Historical Society)

After sobering up, McCarty spent Monday and Tuesday—January 13 and 14—organizing and distributing supplies to the men. He was, he wrote, “sick, most excessive bad.” It wasn’t the first time he wrote that in his diary. Wednesday and Thursday he spent resting in the sergeant major’s quarters. Then he ran to Chatham “about some business” on Friday. On Sunday, he felt the lure of alcohol again. He “took a walk through the country with Mr. Depoe, and bought a barrel of cyder.”

On Monday, Stephen’s severely understrength brigade headed out to look for the enemy. McCarty followed behind, responsible for the wagons. “Our Virginia troops had marched, and I got orders from General Stephen to follow on, and I marched to Westfield, and then to Scotch Plains, it being in the night and very muddy. I got lodgings at one Mr. Halsey’s.” There was was a regiment of Connecticut men in the field as well, commanded by Col. Andrew Ward. These were one-year men whose enlistments would be up in May. Ward's men had been begging to go home since December, however, and were beginning to desert. McCarty and his wagons caught up with the Virginians, commanded by Col. Charles Scott, and joined them in taking quarters at Quibbletown, a village known today as New Market.

Scott and his ninety or a hundred men were walking into a trap set by the enemy, who had grown tired of having their foraging parties ambushed. Though their officer was not meant to be captured, the small group of mounted men had done their job. The Virginians pursued them to Drake’s Farm, near Metuchen, where they "discovered their main body where they were loading hay.” It was not immediately apparent to the Virginians that they were approaching a much larger force than had previously been sent out to guard foragers. Colonel Ward’s surly Connecticuters were nearby, but it is not clear why and command was not unified.

Scott was a popular and aggressive officer and his Virginians attacked immediately. They soon realized they were facing two brigades of British and Hessian troops supported by eight artillery pieces. The Continentals were heavily outnumbered, but fought hard anyway, counting on Ward’s men to back them up. They boldly attacked the enemy line and drove back a battalion of grenadiers. “We attacked the body, and bullets flew like hail,” McCarty wrote. The enemy artillery checked their momentum, but they kept fighting anyway for several minutes. “We stayed about 15 minutes, when we retreated with loss. We drove them first, but at our retreat the balls flew faster than ever.”

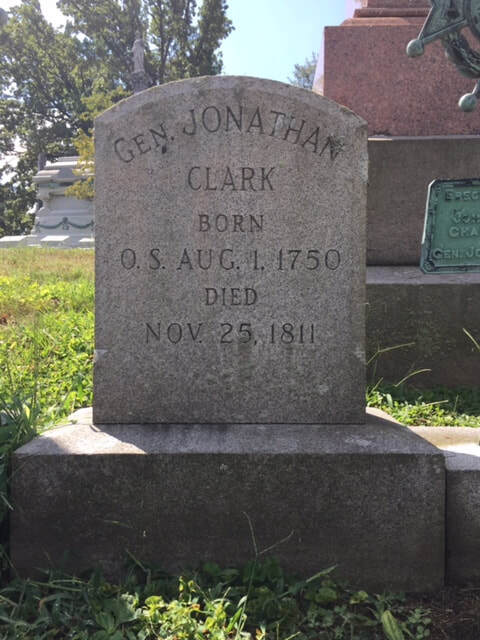

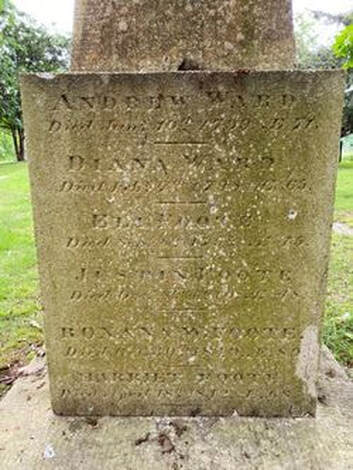

The grave of Col. Andrew Ward V in Guilford, Conn. Ward's great-great grandfather came to New England with John Winthrop in 1630. He was a veteran of the 1745 Siege of Louisbourg (assisting his father as a boy) and the Battle of Lake George in 1760. Though his regiment fought at White Plains, Trenton, and Princeton, his miserable and poorly-equipped men were deserting and begging to go home as early as December when he wrote to Gov. Jonathan Trumbull asking him to prevail upon Washington to let them go home. He appears to have completely lost control of his regiment by March. Ward left Continental service in May but was later made a brigadier general in the Connecticut militia. He voted against the U.S. Constitution at the state ratification convention in 1788. (Findagrave.com)

The murder of the wounded Virginians is confirmed by several sources. General Stephen wrote directly to British general Sir William Erskine to complain that six Virginians “slightly wounded in the muscular parts, were murdered, and their bodies mangled, and their brains beat out, by the troops of his Britannic Majesty.” He warned that such conduct would “inspire the Americans with a hatred to Britons so inveterate and insurmountable, that they never will form an alliance, or the least connection with them.”

Stephen could think of no better threat than a reprise of Gen. Edward Braddock’s defeat in the French and Indian War. Stephen used his credentials as a survivor of that battle to insult and to intimidate the British general with over-the-top threats of Indian cannibalism.

I can assure you, Sir, that the savages after General Braddock’s defeat, notwithstanding the great influence of the French over them, could not be prevailed on to butcher the wounded in the manner your troops have done, until they were first made drunk. I do not know, Sir William, that your troops gave you that trouble. So far does British cruelty, now a days, surpass that of the savages.

In spite of all the British agents sent amongst the different nations, we have beat the Indians into good humour, and they offer their service. It is their custom, in war, to scalp, take out the hearts, and mangle the bodies of their enemies. This is shocking to the humanity natural to the white inhabitants of America. However, if the British officers do not refrain their soldiers from glutting their cruelties with the wanton destruction of the wounded, the United States, contrary to their natural disposition, will be compelled to employ a body of ferocious savages, who can, with an unrelenting heart, eat the flesh, and drink the blood of their enemies. I well remember, that in the year 1763, Lieutenant Gordon, of the Royal Americans, and eight more of the British soldiers, were roasted alive, and eaten up by the fierce savages that now offer their services.

The fundamental British strategy in the Revolution was to empower Loyalists and to pacify rebels and persuade them to accept offers of amnesty. The plan clearly wasn’t working. Shortly after the Battle of Drake’s Farm, a loyalist wrote home: “For these two month[s], or nearly, we have been boxed about in Jersey, as if we had no feelings. Our cantonments have been beaten up; our foraging parties attacked, sometimes defeated, and the forage carried off from us; all travelling between the posts hazardous; and, in short, the troops harassed beyond measure by continual duty.”

The Forage War was a brilliant (and still-unheralded) success for the Americans. Denying the enemy forage and forcing them to live in close quarters for several months had a cumulatively severe impact on them. Howe had more than 31,000 troops at New York on August 27, 1776. When spring came, he had lost between forty and fifty percent of those men to death, desertion, capture, or disease. That was not sustainable.

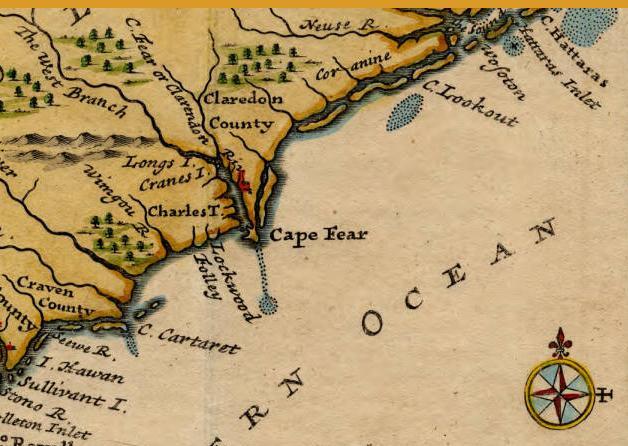

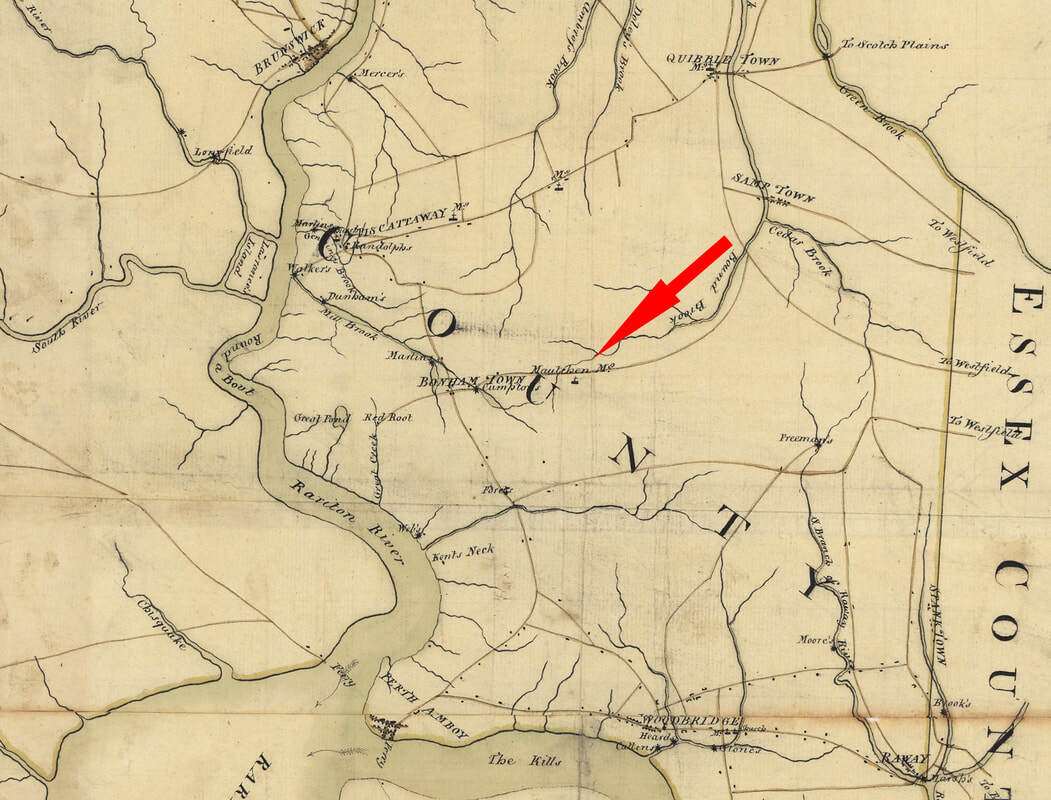

The Battle of Drake's Farm occurred at nor near Metuchen, N.J., half-way between major British outposts at New Brunswick and Perth Amboy. This 1781 map was drawn four years after the engagement. This map is oriented ninety degrees to the right of standard orientation, with the right facing to the north. (Library of Congress)