A sign for store windows printed before the Uniform Monday Holiday Act of 1968. (Library of Congress)

Are we really celebrating Millard Fillmore and Warren Harding today? Not according to federal law. Today’s national holiday is “George Washington’s Birthday.” That’s the simple answer. The full answer is complicated: It’s not actually his birthday today. The holiday actually never falls on Washington’s real birthday. Moreover, we use a different calendar today than we did when he was born. Yet another complication is that in several states it is also “Presidents’ Day.”

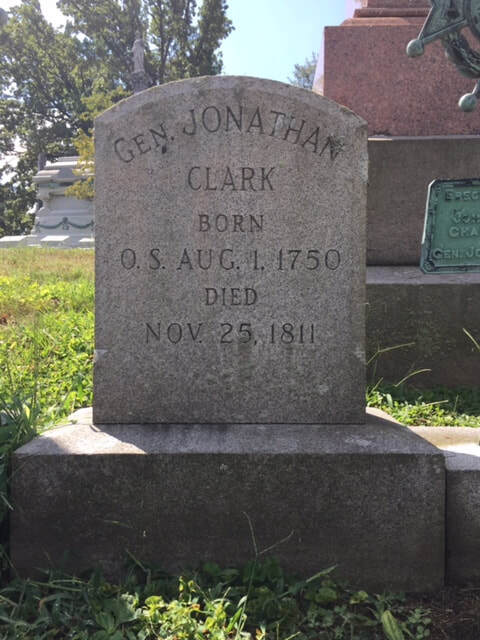

Washington was born on February 11, 1731…under the Julian Calendar. This was the old calendar established under Julius Caesar. Pope Gregory moved the Catholic world to a more accurate calendar in 1582, but Protestant England, under Queen Elizabeth, wasn’t bound by the change. Leap year differences put Britain and the America colonies eleven days behind the rest of the western world. Moreover, New Year’s Day was March 25 under the old calendar, not January 1. Consequently, when the British Empire finally changed to the Gregorian Calendar in 1752, Washington’s birthday changed from February 11, 1731 to February 22, 1732. Both dates are correct, but the proper way to note the Julian date is “February 11, 1731 (O.S.).” The abbreviation stand for “old style.”

Washington’s Birthday was declared a holiday by Congress in 1879. Many people don’t realize that Congress has no authority to declare holidays (days off) for anyone other than federal employees and residents of the District of Columbia. States, however, followed the federal government’s lead and Washington’s Birthday was celebrated for decades on February 22. Abraham Lincoln’s birthday was never a federal holiday, but was celebrated by many states on February 12—just ten days before Washington’s birthday. In the 1950s, there was an effort to establish a third holiday, President’s Day, to honor “the office of the presidency” on March 4 – the original day of quadrennial inaugurations. Though some states adopted the new holiday, Congress declined to in the belief that three holidays in rapid succession were too many.

Washington’s Birthday was declared a holiday by Congress in 1879. Many people don’t realize that Congress has no authority to declare holidays (days off) for anyone other than federal employees and residents of the District of Columbia. States, however, followed the federal government’s lead and Washington’s Birthday was celebrated for decades on February 22. Abraham Lincoln’s birthday was never a federal holiday, but was celebrated by many states on February 12—just ten days before Washington’s birthday. In the 1950s, there was an effort to establish a third holiday, President’s Day, to honor “the office of the presidency” on March 4 – the original day of quadrennial inaugurations. Though some states adopted the new holiday, Congress declined to in the belief that three holidays in rapid succession were too many.

In 1968, Congress passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act, guaranteeing three-day weekends for Washington’s Birthday, Memorial Day, Labor Day, Columbus Day, and Veterans Day. A proposal to also replace Washington’s Birthday with a generic “President’s Day” was specifically rejected. However, because the holiday was set to be celebrated on the third Monday in February, it was guaranteed to always fall between Lincoln’s and Washington’s birthdays yet never on either. This invited use of the generic term “President’s Day (with the apostrophe sometimes after the “s.”) Advertisers are usually blamed for popularizing the term.

Though the federal holiday is Washington’s Birthday, it is state law that determines days off for most Americans. Only seven states celebrate Washington alone on the third Monday in February. Virginia calls it “George Washington Day.”Illinois, Iowa, Michigan, Louisiana, and New York call it “Washington’s Birthday.” Twenty-two states celebrate “President’s Day” (with varying punctuation). The rest of the states name the holiday after Washington and someone else, most often Lincoln, but also Jefferson (Alabama), civil rights activist Daisy Bates (Arkansas), and all presidents (Maine and Arizona).

Though the federal holiday is Washington’s Birthday, it is state law that determines days off for most Americans. Only seven states celebrate Washington alone on the third Monday in February. Virginia calls it “George Washington Day.”Illinois, Iowa, Michigan, Louisiana, and New York call it “Washington’s Birthday.” Twenty-two states celebrate “President’s Day” (with varying punctuation). The rest of the states name the holiday after Washington and someone else, most often Lincoln, but also Jefferson (Alabama), civil rights activist Daisy Bates (Arkansas), and all presidents (Maine and Arizona).

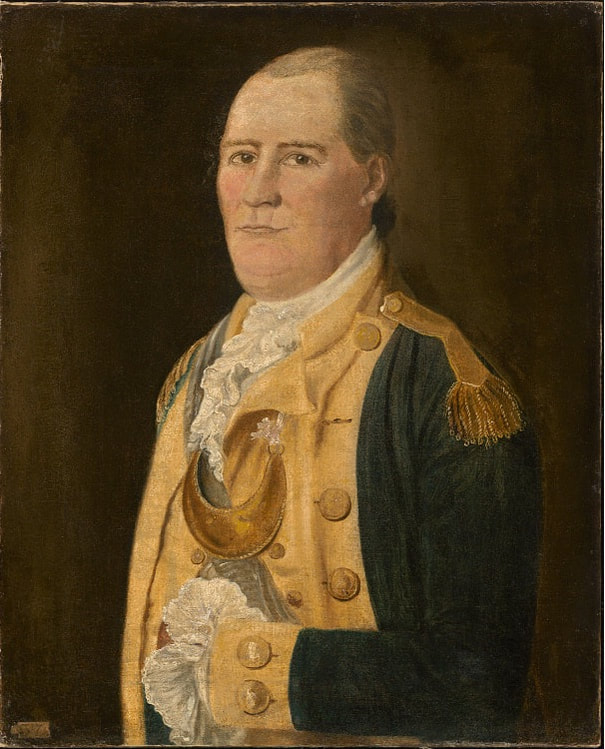

The grave of 8th Virginia captain and major Jonathan Clark indicates that he was born under the Julian calendar. (author)

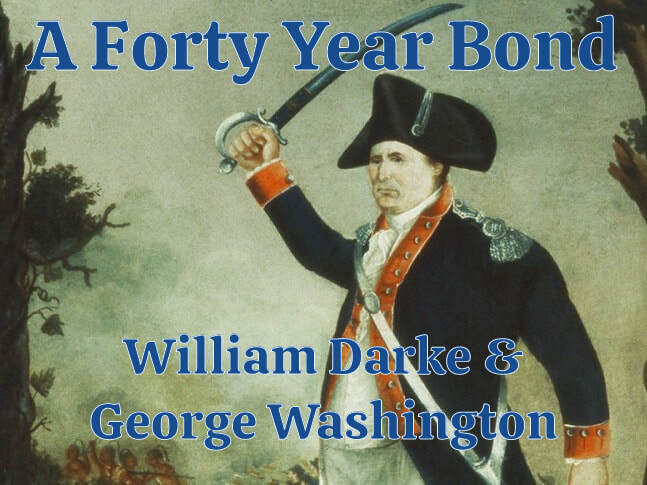

Under our present Constitution, the United States has had forty-five presidents. Some have been great and some have not. Reputations have waxed and waned as attitudes change and new biographies are written. Celebrating “President’s Day” seems to make no more sense that celebrating “Congress Day” or “Supreme Court Day.” In the fact, the notion of a “President’s Day” has vaguely monarchist overtones. Surely, we can all think of several presidents who don’t deserve the honor. Washington, however, stands high above the rest. He is rightly known as the father of the country. He effectuated a great break with the past, establishing durable and free government in part by repeatedly declining to cling to power. Only one other president rivals his claim to greatness.

Holidays have always been the subject of civic activism. Veterans Day was moved back to November 11 in 1975 to align with the World War I armistice. Columbus Day has been replaced by “Indigenous People’s Day” in Florida, Hawaii, Alaska, Vermont, South Dakota, New Mexico, and Maine. If you live in a place (such as, believe it or not, Washington State) that celebrates “President’s Day,” you might want to call your state legislator and point out that Chester Arthur doesn’t belong on the same holiday stage as George Washington.

Holidays have always been the subject of civic activism. Veterans Day was moved back to November 11 in 1975 to align with the World War I armistice. Columbus Day has been replaced by “Indigenous People’s Day” in Florida, Hawaii, Alaska, Vermont, South Dakota, New Mexico, and Maine. If you live in a place (such as, believe it or not, Washington State) that celebrates “President’s Day,” you might want to call your state legislator and point out that Chester Arthur doesn’t belong on the same holiday stage as George Washington.