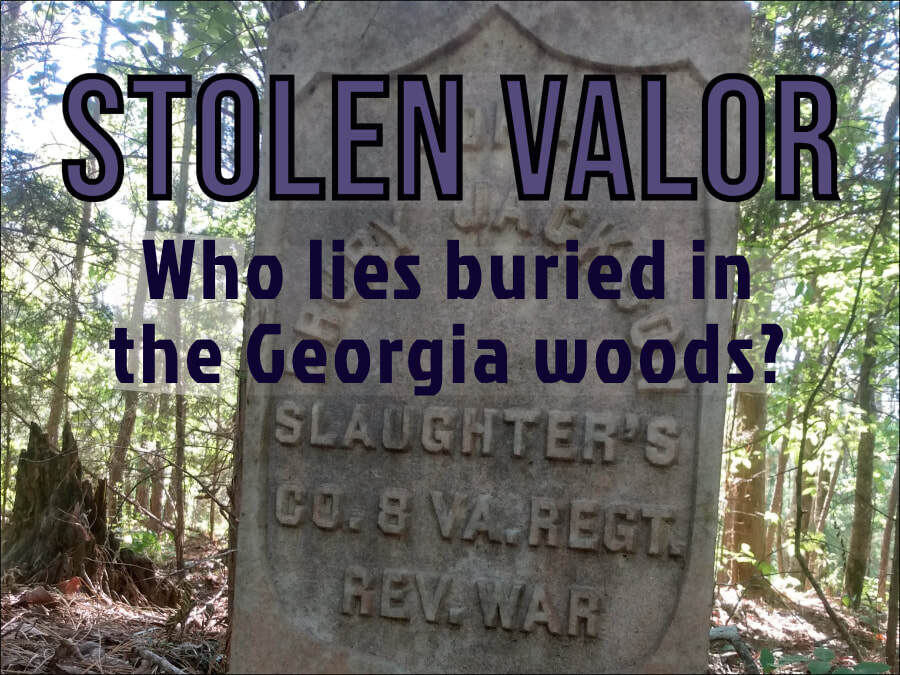

At home, a County Committee was formed to enforce the Virginia Association, an agreement to boycott British goods. In addition to being parish rector and a delegate to the Convention, Muhlenberg was chairman of the committee. Other members of the Dunmore Committee included Francis Slaughter, Abraham Bird, Taverner Beale, John Tipton, and Abraham Bowman. Taverner Beale’s farm, “Mount Airy remains intact two miles south of Mount Jackson.

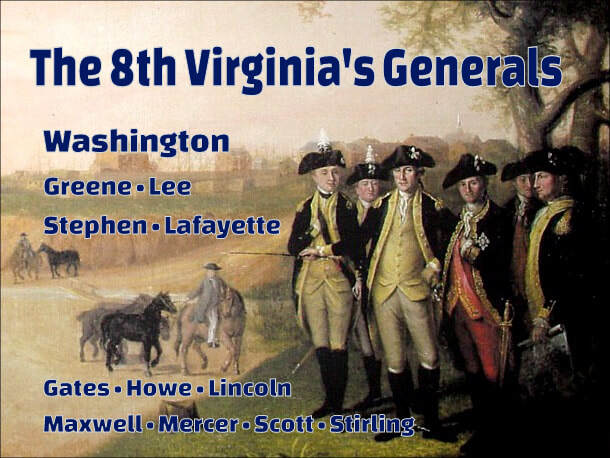

As things became more serious, more than 80 young men from Dunmore County formed The First Inde- pendent Company of Dunmore, a volunteer military organization separate from the county militia (technically still under the governor’s control). Taverner Beale was probably captain of the Dunmore Volunteers, with Jonathan Clark as his lieutenant. Abraham Bowman, Richard Campbell, John Steed, Matthias Hite, Leonard Cooper, Philip Huffman, Jacob Parrot, and Clark’s younger brother John also belonged. These men would later be officers in Colonel Muhlenberg’s 8th Virginia Regiment.