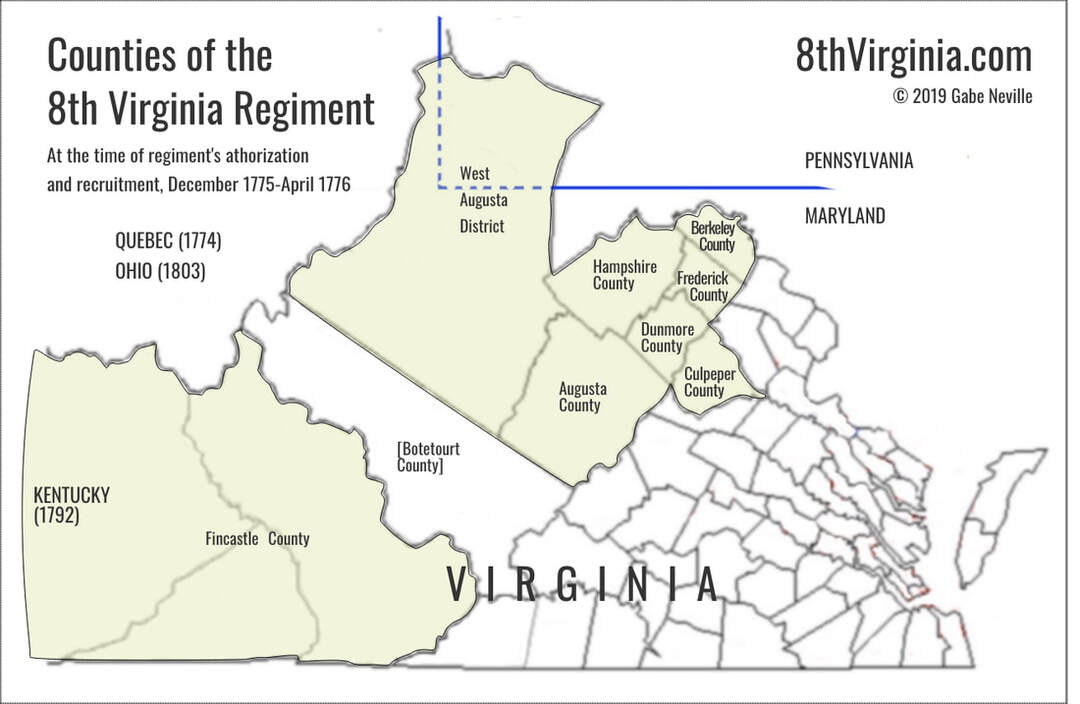

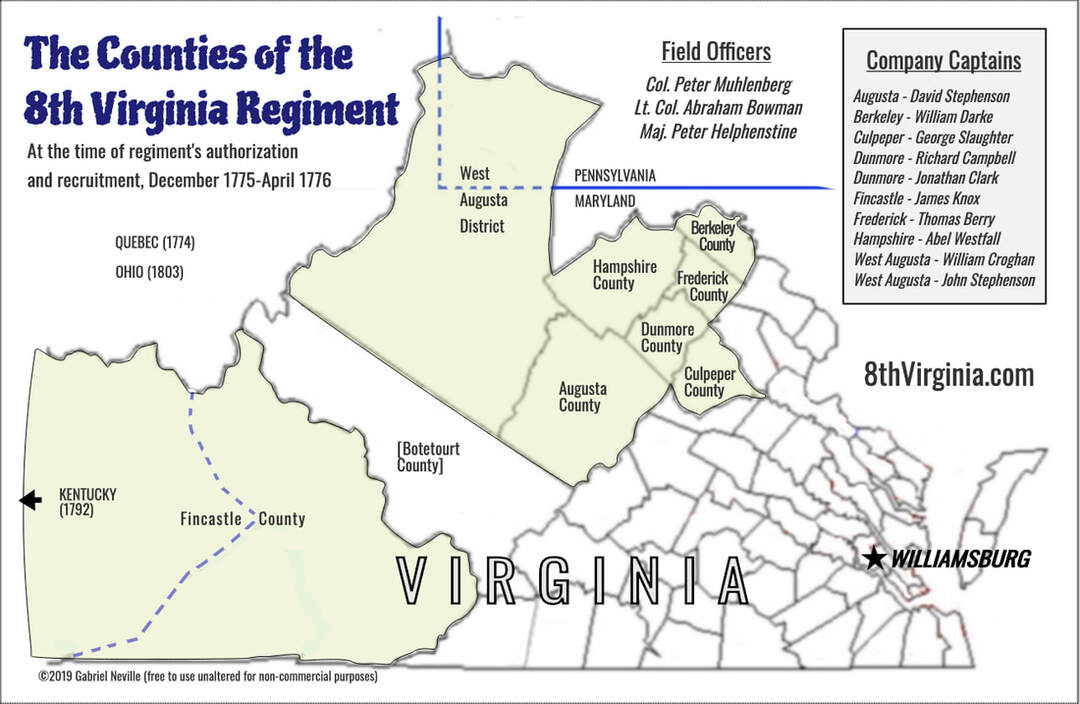

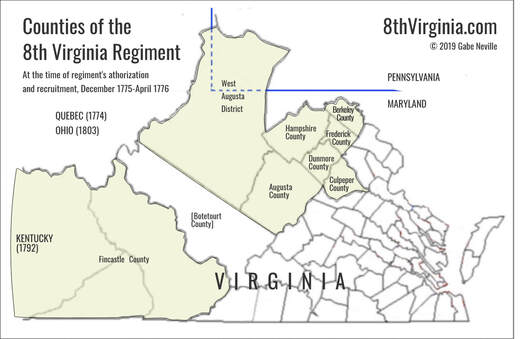

A newly-created map of the 8th Virginia's recruiting counties shows that the regiment was largely composed of frontiersmen and pioneers. It is helpful to visualize how the regiment raised its ten companies in the westernmost settled areas of the province (Virginia wasn't a state, yet). This made the regiment unique in several ways. They were ethnically and religiously different from the rest of Virginia. Soldiers, some of whom were subsistence hunters, were typically better marksmen than the average soldier. Their motives for fighting were less focused on taxes and trade and more focused on their desires to head west--something the King had forbidden.

Political geography has changed. All of these counties have been divided, some within months of the regiment's formation. West Virginia, which is not shown, was created in 1863 and would occupy the left-center of the map. The disputed northeast part of the Augusta District is now southwest Pennsylvania, including Pittsburgh. Western Fincastle County became Kentucky County in 1776 and the Commonwealth of Kentucky in 1792. Most Americans are unaware that beginning in 1774, Ohio and lands west of it were part of the Province of Quebec. This, technically at least, extended holdover French civil institutions to the border of settled Virginia. Quebec had no elected legislature and had been allowed to keep its Catholic institutions. Both facts were seen by Virginians as sure signs of creeping tyranny.

The Soldiers Page lists the various companies and the counties from which they came. In brief: the West Augusta District and Dunmore County each raised two companies. Augusta, Berkeley, Culpeper, Fincastle, Frederick, and Hampshire counties each contributed one. Initially called the "German Regiment" and long remembered that way, the map also shows how wide-ranging and diverse the zone of recruitment was. The lower (northern) Shenandoah Valley counties of Berkeley, Frederick, and Dunmore had significant populations and all three field officers were from that area. Culpeper, the only Piedmont county, had a smaller German population that descended from the Germanna Colony. The other counties were predominantly Scotch-Irish and English.

Political geography has changed. All of these counties have been divided, some within months of the regiment's formation. West Virginia, which is not shown, was created in 1863 and would occupy the left-center of the map. The disputed northeast part of the Augusta District is now southwest Pennsylvania, including Pittsburgh. Western Fincastle County became Kentucky County in 1776 and the Commonwealth of Kentucky in 1792. Most Americans are unaware that beginning in 1774, Ohio and lands west of it were part of the Province of Quebec. This, technically at least, extended holdover French civil institutions to the border of settled Virginia. Quebec had no elected legislature and had been allowed to keep its Catholic institutions. Both facts were seen by Virginians as sure signs of creeping tyranny.

The Soldiers Page lists the various companies and the counties from which they came. In brief: the West Augusta District and Dunmore County each raised two companies. Augusta, Berkeley, Culpeper, Fincastle, Frederick, and Hampshire counties each contributed one. Initially called the "German Regiment" and long remembered that way, the map also shows how wide-ranging and diverse the zone of recruitment was. The lower (northern) Shenandoah Valley counties of Berkeley, Frederick, and Dunmore had significant populations and all three field officers were from that area. Culpeper, the only Piedmont county, had a smaller German population that descended from the Germanna Colony. The other counties were predominantly Scotch-Irish and English.