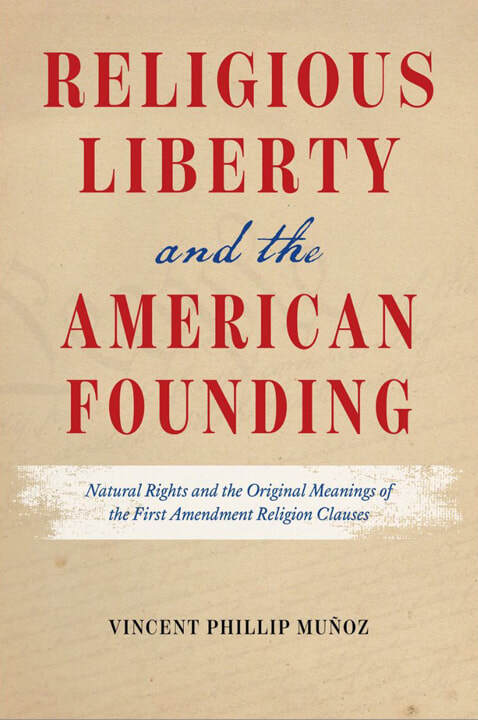

Religious Liberty and the American Founding

Vincent Phillip Muñoz (University of Chicago Press, 2022)

We are told in the Declaration of Independence that certain rights are “unalienable.” Have you ever wondered what that means? Are other rights “alienable?” Notre Dame’s Professor Vincent Phillip Muñoz, author of Religious Liberty and the American Founding, wants you to ask that question.

The importance of the First Amendment is universally understood. It is the most-discussed part of the Constitution and the courts have ruled on its meaning many times.

The importance of the First Amendment is universally understood. It is the most-discussed part of the Constitution and the courts have ruled on its meaning many times.

Professor Muñoz argues persuasively, however, that scholars, lawyers, and judges have all done a consistently sloppy job of seeking to understand what the founders actually meant by the words they used. So much so, in fact, that the original meaning of the Establishment and Free Expression clauses has effectively been lost. The result is that the text has become an ideological Rorschach test. It can be made to mean almost anything. “The consensus that the Founders’ understanding should serve as a guide has produced neither agreement nor coherence in church-state jurisprudence,” Dr. Muñoz writes. “Indeed, it has produced the opposite; it seems that almost any and every church-state judicial position can invoke the Founders’ support.

Many readers will be surprised to hear that the Founders themselves are largely to blame for this. The language of the First Amendment itself (“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof”) is not very precise. The reason for this is that “Many, if not most, of the individuals who drafted the First Amendment did not think it was necessary.”[2] Establishment was a state issue and the Federal constitution already banned religious tests in Article VI.[3] It was the Anti-Federalists who insisted on the Bill of Rights, but they were in the minority in the 1st Congress.

Many readers will be surprised to hear that the Founders themselves are largely to blame for this. The language of the First Amendment itself (“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof”) is not very precise. The reason for this is that “Many, if not most, of the individuals who drafted the First Amendment did not think it was necessary.”[2] Establishment was a state issue and the Federal constitution already banned religious tests in Article VI.[3] It was the Anti-Federalists who insisted on the Bill of Rights, but they were in the minority in the 1st Congress.