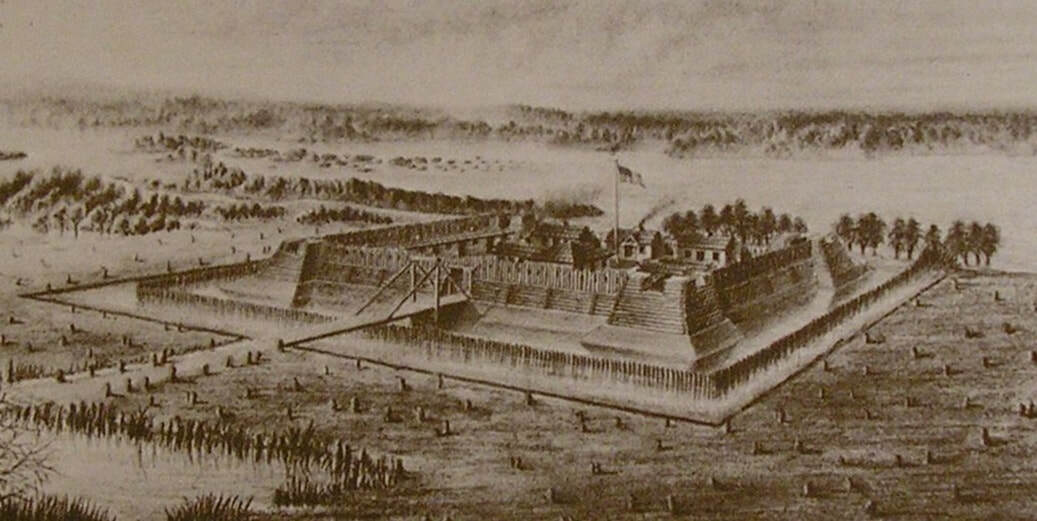

George Slaughter oversaw the construction of Fort Nelson at Louisville. (1855 image)

Clark witnessed the return of hundreds of kidnapped children at the end of Pontiac's Rebellion.

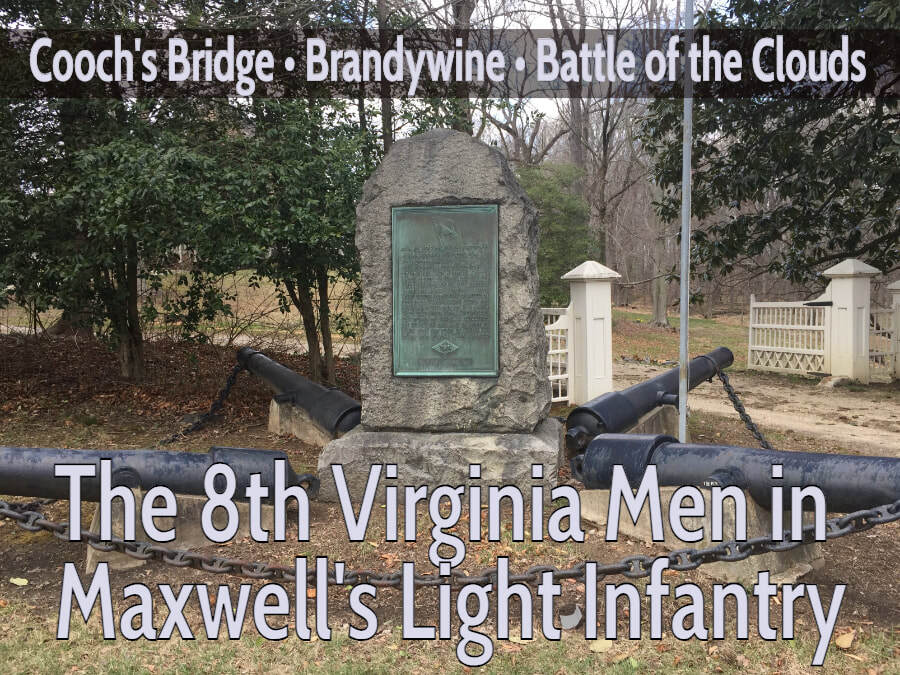

Virginia authorized four battalions of six-month volunteers in June 1778. These were state (not Continental) soldiers intended to reinforce Washington's army. Slaughter was chosen to lead one of the battalions. However, in August Congress advised the Commonwealth that the battalions would not be needed and the half-recruited units were disbanded. It is possible, however, that Slaughter's battalion was ultimately repurposed rather than dissolved.

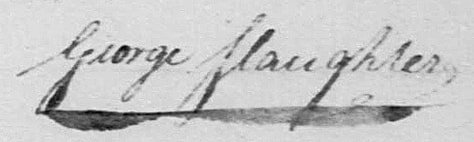

George's Slaughter's signature.

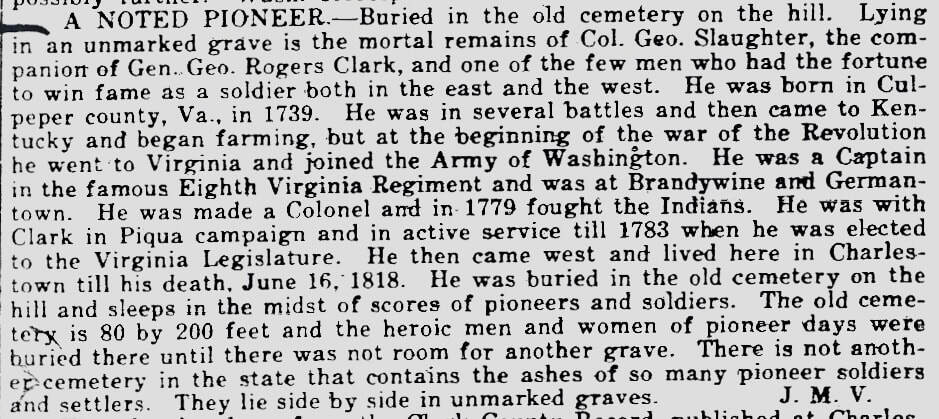

In 1923, the Culpeper Exponent reprinted an 1898 story originally from a Charlestown, Indiana newspaper giving a brief biography and identifying the site of Slaughter's unmarked grave. (Thanks to Al McLean)

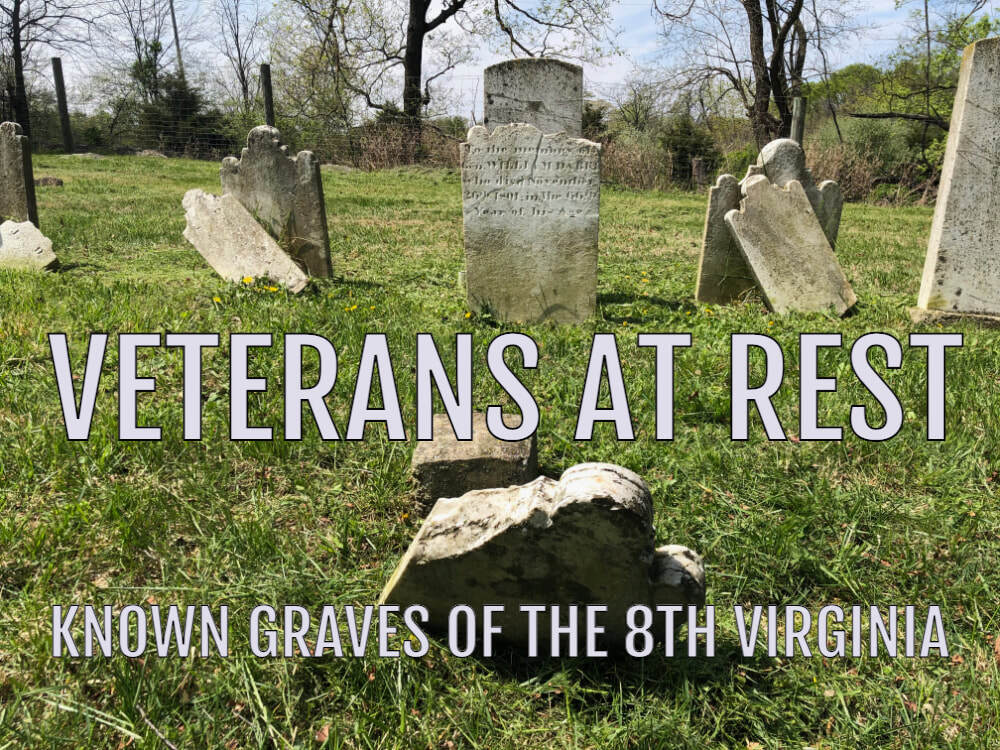

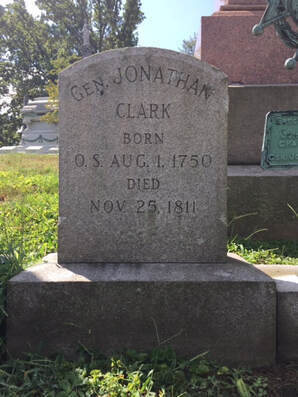

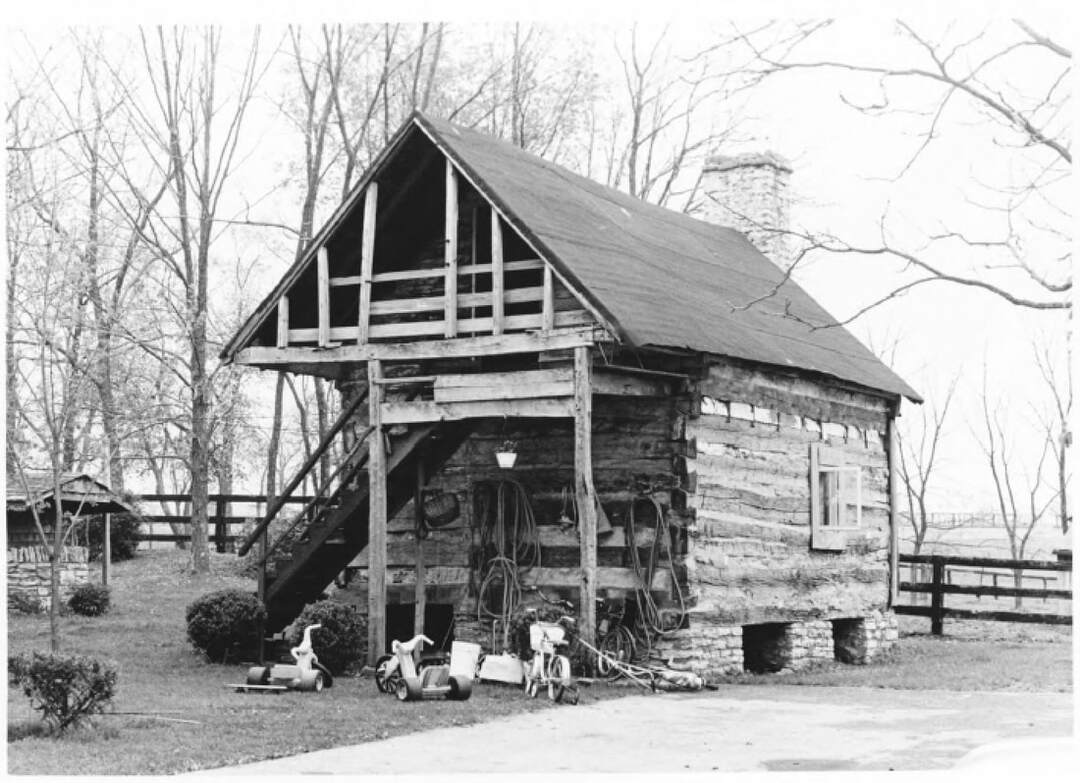

Slaughter is buried in this abandoned cemetery in Charlestown, Indiana. His grave is unmarked. Indiana's first governor, Jonathan Jennings, was also originally buried here in an unmarked grave after he died a penniless alcoholic. (Indiana SAR)

Like many 8th Virginia veterans who were prominent and important in their day, Slaughter has been largely forgotten. It is never too late for Louisville (or Culpeper, or Charleston) to memorialize him.