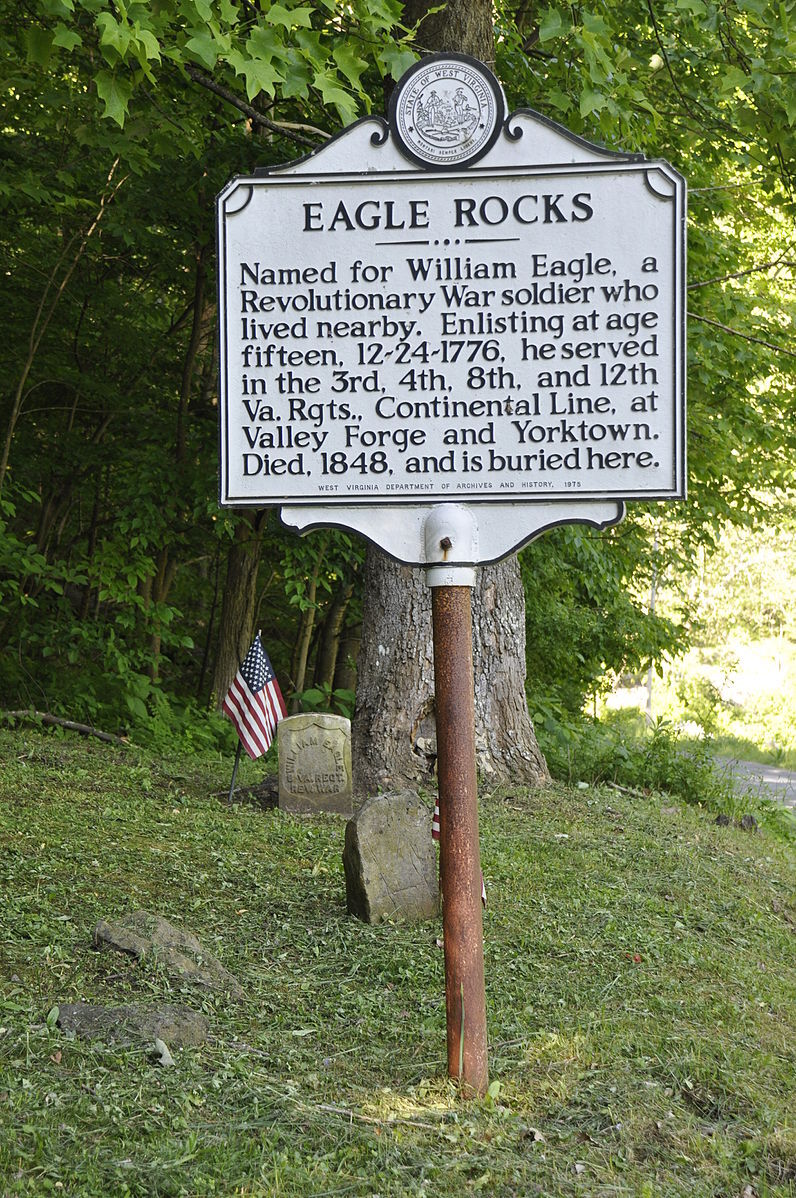

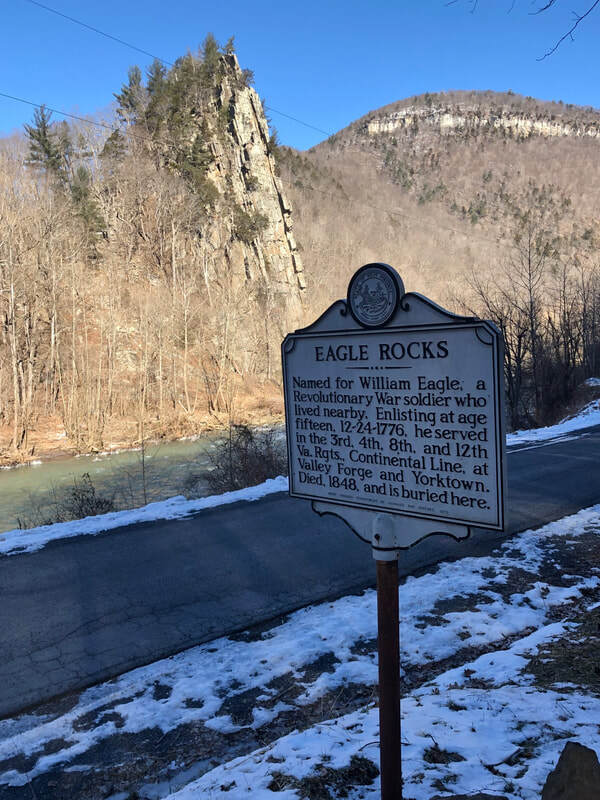

A historic marker in Pendleton County, West Virginia tells the story of fifteen year-old William Eagle, who enlisted in the 8th Virginia on Christmas Eve, 1776. This was the Revolution's darkest hour. Washington's dwindling army had fled from the British across New Jersey and was now huddling, frozen by fear and cold on the West Bank of the Delaware. At a moment when few were willing to enlist, this teenage patriot stepped forward.

Except it isn't true. Eagle's pension gives the same date that appears on the sign, but they are both wrong. The sign probably takes its date from the pension. As far as we know, Eagle served honorably and well. But he didn't enlist until December of 1777 when he was sixteen years old. The evidence is clear.

First, His name appears nowhere in the muster or pay rolls for 1777, and the "commencement of pay" date on his first pay roll entry is February 1, 1778.

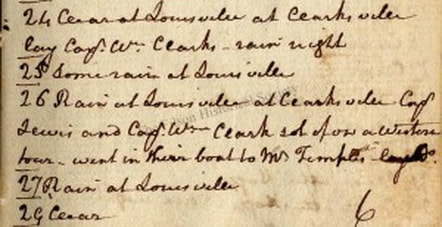

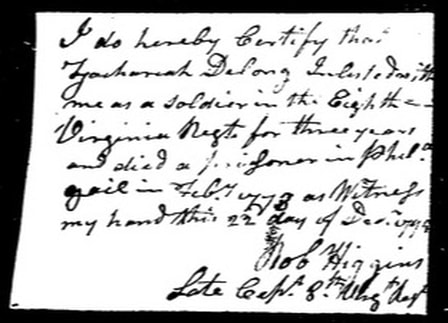

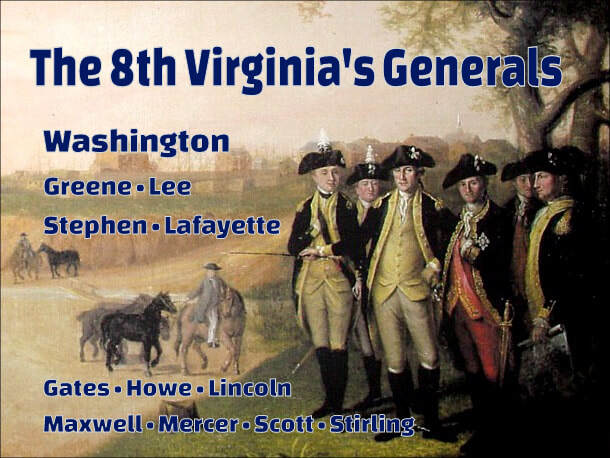

Second, His pension affidavit claims that he "enlisted for the term of three years, on or about the 24th day of December in the year 1776, in the state of Virginia in the Company commanded by Captain Stead or Sted or Steed, in the Regiment commanded by Colonel Nevil or Neville." Colonel John Neville (no known relation to me) commanded the regiment after it was folded into the 4th Virginia in the fall of 1778. Had Eagle enlisted in the regiment in December of 1776 and joined it in January of 1777 he would certainly have mentioned Colonel Abraham Bowman, who became a "supernumerary" officer and was released from service when the regiments merged. Eagle served under Bowman only for a short while and, consequently, did not mention him. Eagle got the names right (Neville and Steed), but the year wrong.

Third, the term of his enlistment is consistently recorded as for 3 years or the length of the war (which ever was shorter). Soldiers who enlisted in 1777 or later enlisted under these terms. Virginia soldiers who enlisted in 1776 signed up for two years. (Someone might argue that a date so late in the year might have been treated differently, but I'm not aware of any examples of this.)

The date of his enlistment is not recorded anywhere in the surviving official records. From the evidence, however, it seems certain that he in fact enlisted "on or about the 24th day of December" in the year of 1777--not 1776--and joined the regiment at Valley Forge about a month later. Eagle is not the only veteran who got the dates of his service wrong when applying for a pension decades later. It is an understandable error for an old man to make. The State of West Virginia might, however, want to invest in an updated marker.

So what happened to William Eagle? After nearly two years of service he was “discharged for inability” on September 1, 1779. Tradition has it that he had a broken arm. Whatever his injury was, it saved him capture following the surrender of the Virginia Line after the Siege of Charleston in May of 1780.

William Eagle’s grave is by Eagle Rocks, a steep peak near the headwaters of the Potomac in West Virginia’s remote Smoke Hole Canyon. Ross B. Johnston wrote in his book West Virginians in the Revolution that the veteran named his son George Washington Eagle, and he nearly lost his life one day climbing his namesake peak in an attempt to capture some baby eagles.

Except it isn't true. Eagle's pension gives the same date that appears on the sign, but they are both wrong. The sign probably takes its date from the pension. As far as we know, Eagle served honorably and well. But he didn't enlist until December of 1777 when he was sixteen years old. The evidence is clear.

First, His name appears nowhere in the muster or pay rolls for 1777, and the "commencement of pay" date on his first pay roll entry is February 1, 1778.

Second, His pension affidavit claims that he "enlisted for the term of three years, on or about the 24th day of December in the year 1776, in the state of Virginia in the Company commanded by Captain Stead or Sted or Steed, in the Regiment commanded by Colonel Nevil or Neville." Colonel John Neville (no known relation to me) commanded the regiment after it was folded into the 4th Virginia in the fall of 1778. Had Eagle enlisted in the regiment in December of 1776 and joined it in January of 1777 he would certainly have mentioned Colonel Abraham Bowman, who became a "supernumerary" officer and was released from service when the regiments merged. Eagle served under Bowman only for a short while and, consequently, did not mention him. Eagle got the names right (Neville and Steed), but the year wrong.

Third, the term of his enlistment is consistently recorded as for 3 years or the length of the war (which ever was shorter). Soldiers who enlisted in 1777 or later enlisted under these terms. Virginia soldiers who enlisted in 1776 signed up for two years. (Someone might argue that a date so late in the year might have been treated differently, but I'm not aware of any examples of this.)

The date of his enlistment is not recorded anywhere in the surviving official records. From the evidence, however, it seems certain that he in fact enlisted "on or about the 24th day of December" in the year of 1777--not 1776--and joined the regiment at Valley Forge about a month later. Eagle is not the only veteran who got the dates of his service wrong when applying for a pension decades later. It is an understandable error for an old man to make. The State of West Virginia might, however, want to invest in an updated marker.

So what happened to William Eagle? After nearly two years of service he was “discharged for inability” on September 1, 1779. Tradition has it that he had a broken arm. Whatever his injury was, it saved him capture following the surrender of the Virginia Line after the Siege of Charleston in May of 1780.

William Eagle’s grave is by Eagle Rocks, a steep peak near the headwaters of the Potomac in West Virginia’s remote Smoke Hole Canyon. Ross B. Johnston wrote in his book West Virginians in the Revolution that the veteran named his son George Washington Eagle, and he nearly lost his life one day climbing his namesake peak in an attempt to capture some baby eagles.

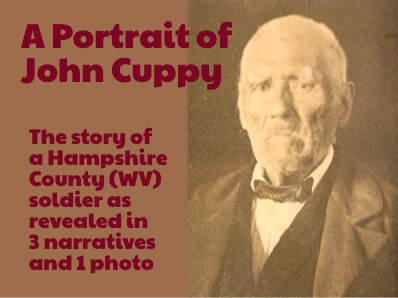

An undated photo of the grave.

A January, 2019 photo shows grave needing some care.

Eagle Rocks is seen across a small road from William Eagle's grave.

(Revised December 21, 2019)