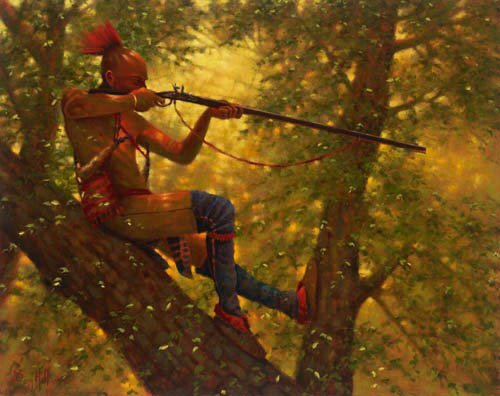

"Well Positioned" by Doug Hall (doughallgallery.com)

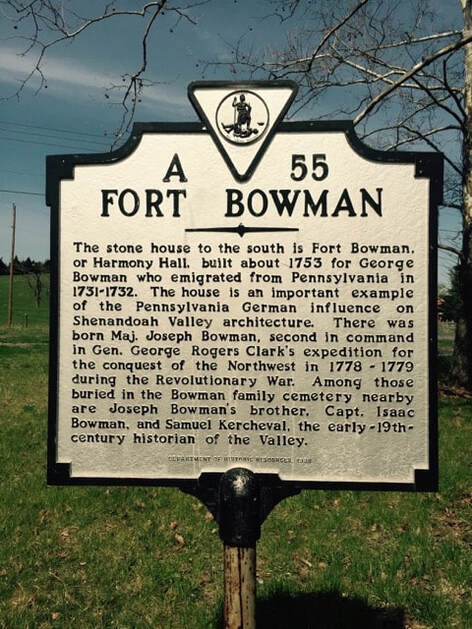

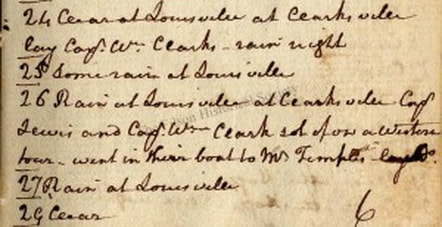

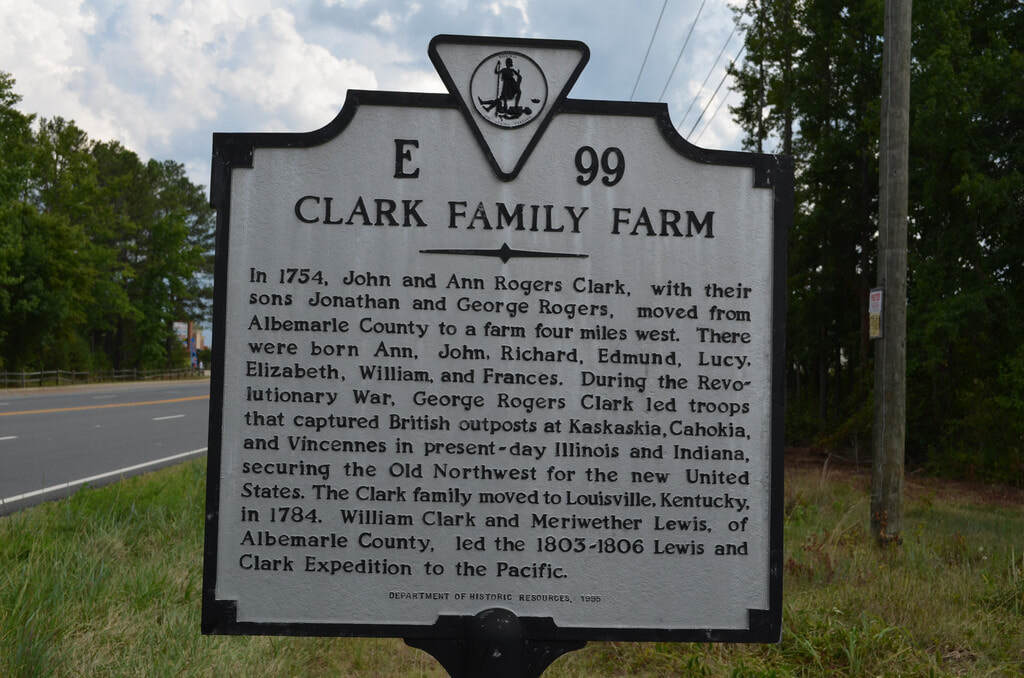

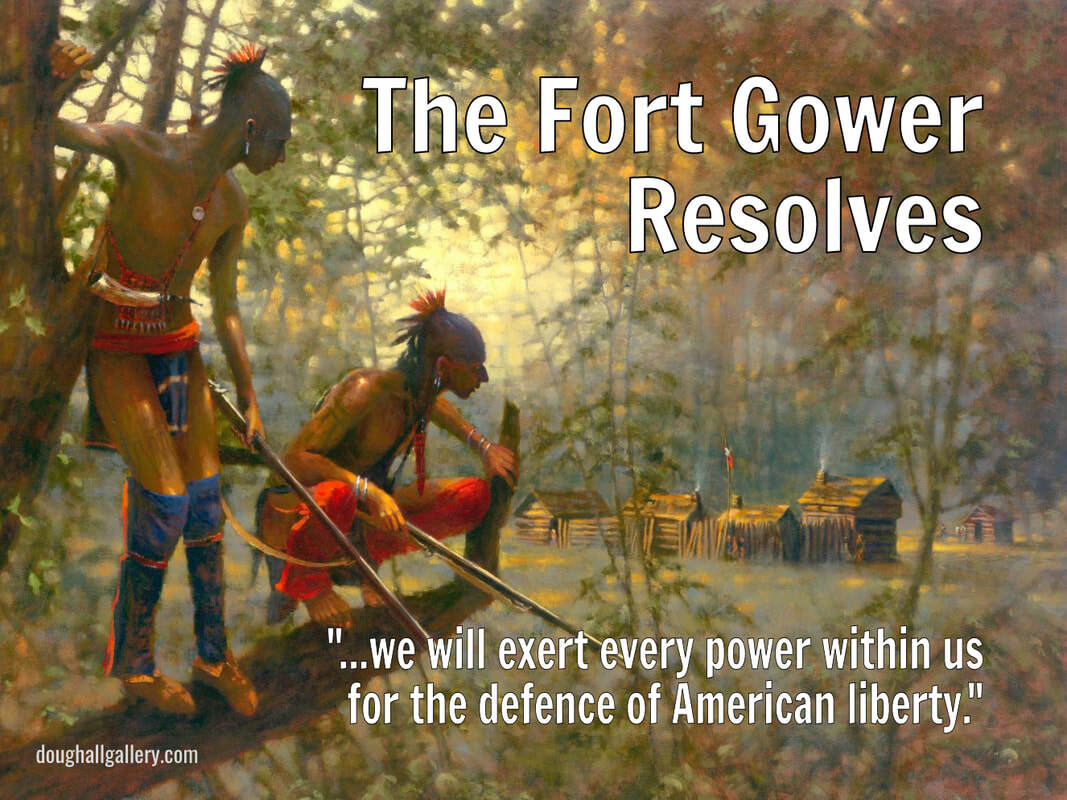

On March 5, 1833 an old man named John Duncan walked into the Franklin County, Illinois courthouse and applied for a Revolutionary War pension. His father, he said, had been killed by Indians in Washington County, Virginia, when he was nine or ten years old. He recorded his own 20-year story of virtually nonstop Indian fighting, including the famous Vincennes campaign led by General George Rogers Clark (younger brother of 8th Virginia Captain Jonathan Clark). In his own words he had lived "in a country in a constant state of alarm, and liable to be called on at any moment."

According the the affidavit, “He never was regularly mustered into or out of service," he said. "He never was discharged regularly. He received some little pay, but does not now recollect how much. He is unacquainted with the names of any Regular or Continental officers or companies, nor ever served with any.... He never was regularly enrolled in any company or corps, unless it might be Genl Clark’s or Col Hays’s. He belonged to none at home. He has no documentary evidence of his service; he knows of no living witness who can testify personally as to his service....”

The death of Duncan's father was noted at the time by Daniel Boone, who collected the ball-head war club that had been used to kill him. War clubs were left by Indians as macabre calling cards beside their victims. Boone gave the club to Maj. Arthur Campbell who wrote to William Preston on October 1, 1774, "Mr. Boone preparing to go in search of the enemy...thinks it is the Cherokees that is now annoying us." This was at the height of Lord Dunmore's War, a conflict fought by Virginia primarily against the Ohio-based Shawnee over control of Kentucky.

In 1905, David E. Johnston, a descendent of 1778 New River settlers, wrote, "The life of these people was a long and dangerous struggle.... A race of men unused to war and ever present dangers, would have been helpless before such foes as these wild beasts and the Indians. People coming from the old world, no matter how thrifty and adventurous, could not hold their own on the frontier.... Every man from childhood was accustomed to the use of the rifle, and even a boy at twelve years was regarded old enough to have a gun, and was soon taught how to use it. He at least could make a good fort soldier. The war was never ending, for even the times of so-called peace were broken by forays and murders. A man might grow from boyhood to middle age on the border, and yet never recall a single year in which some of his neighbors were not killed by the Indians."

In 1905, David E. Johnston, a descendent of 1778 New River settlers, wrote, "The life of these people was a long and dangerous struggle.... A race of men unused to war and ever present dangers, would have been helpless before such foes as these wild beasts and the Indians. People coming from the old world, no matter how thrifty and adventurous, could not hold their own on the frontier.... Every man from childhood was accustomed to the use of the rifle, and even a boy at twelve years was regarded old enough to have a gun, and was soon taught how to use it. He at least could make a good fort soldier. The war was never ending, for even the times of so-called peace were broken by forays and murders. A man might grow from boyhood to middle age on the border, and yet never recall a single year in which some of his neighbors were not killed by the Indians."

Duncan’s career of Indian fighting, colorful as it was, did not qualify him for a Revolutionary War pension. Most of it happened after the war was over (he was about 18 at the time of the victory at Yorktown).

A ball head war club of the type used to kill Duncan's father.

The pension affidavit, however, is great reading for anyone interested in early frontier history. It was transcribed by C. Leon Harris and is one of thousands Harris and his partners at RevWarApps.com have transcribed and put online. These affidavits have long been largely ignored by historians, who have been suspicious of them as the late memories of old men eager for money. Used carefully, however, they are a great resource to my research—especially when they corroborate each other or fill in blanks in the record. Duncan’s affidavit can be read here.

Though he lived for a time in an area that recruited men for the 8th Virginia, Duncan was never connected with the regiment.

(Updated May 31, 2021 and August 28, 2021.)

Though he lived for a time in an area that recruited men for the 8th Virginia, Duncan was never connected with the regiment.

(Updated May 31, 2021 and August 28, 2021.)