He immediately assembled his new Army at Staunton, a small town in Augusta County, lying about 20 miles to the Westward of the South Mountain, from whence he marched Aug[us]t 18th and proceeded directly to Holstein [Holston], a settlement upon the frontiers where the Indians were then ravaging; but upon the approach of the army retreated with their booty. The Col. finding they would not come to a decisive engagement so far from home, determined to pursue them to their towns, to expedite which he encamped his army on an island formed in the river Holstein, generally known by the name of the Long Island, untill such time as he could be reinforced with provisions and men, upon which there were severall draughts taken out of the Militia[.]

General Washington at the same time petitioning for more troops, and a draught of the Militia being granted, it fell to my lot to go as one. At that time I taught a school in Augusta County, but being zealous for government was determined not to go, but finding I was not able to withstand their power, which was very arbitrary in that part, I thought it better to enter into the service against the Indians than to go into actual service against my Countrymen. Accordingly some troops were raising at that time by Act of the Convention of Virginia (to be stationed at the different passes on the Ohio to keep the Shawneese &c in awe and to prevent their incursions) upon these terms, vizt that they should enlist for the term of two years, that they should not be compelled to leave the said frontiers or be entred into the Continental service without their own mutual consent, as also that of the legislator.

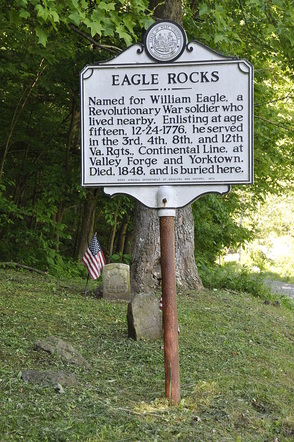

Taking this to be the only method of scree[n]ing myself from being deemed a Tory and also of preventing my being forced into the Continental service, I enlisted the third of Septemb[e]r into Capt. Michael Bowyers's Company of Riflemen, to be stationed at the mouth of the Little Kennarah [Kanawha] upon the River Ohio.

Soon after we marched in company with 150 militia, to the assistance of Coll. Smith, who still continued on the Long Island. We had several skirmishes with the Indians during our march, without any considerable loss on either side. Sept[embe]r 19th we joined the main body, and on the 22d decamped and proceeded towards the Cherokee towns. The enemy continued to harrass us in our march with numberless attacks, sometimes appearing on our front, sometimes upon our flank, so giving us a brisk fire for some minutes, would immediately retreat into the woods. Thus we continued our march thro' the woods the space of three weeks, about which time we received intelligence from our spies and from some prisoners that had escaped, that the Indians had removed every thing from their towns into the mountains, had cut down their corn & set fire to every thing they could not carry away which they thought might be of service to the white army.

Upon the confirmation of this account Coll. Smith being persuaded they would never hazard a general engagement, and knowing that his army was but badly supplied with provisions, sent severall companys back into the different Settlements where the Savages were still making incursions and murdring the inhabitants; the Company to which I belonged was one of this number. We were sent to a place lying in the Allegany mountains (upon the banks of the River Monongalia) known by the name of Tygar's [Tygart] Valley where we were ordered during the winter, in order both to defend the Inhabitants and to make canoes to carry us down the river to the place where we were to be stationed the ensuing Spring; in which place I was made Serg' in which I continued during my stay in the army.

In the mean time the Indians, finding the Virginians fully bent to search them out and an army of Carolina troops approaching on the other side, sent Deputies to Col. Smith to sue for peace, which was granted upon their delivering up the prisoners, and restoring the goods that they carried out of the Settlements. Hereupon the Militia was disbanded, and the other troops that were enlisted on the aforementioned terms were distributed amongst the frontier settlements during the winter.

About this time the war was very hot in the Jerseys, and the Congress determining to recruit their army as soon as possible in the Spring, sent a remonstrance to the Convention of Virginia, alledging that they had a number of troops on their frontiers that were of very little or no service to the country, as the Indians were peacably inclined. Therefore they desired that they should be sent to the assistance of the Continental army as early in the Spring as they possibly could. The Convention immediately repealed the Act on which the troops were raised and directly entered them into the Continental service, and issued forth commissions for the raising of six new Battalions, amongst which the troops formerly raised for the defence of the back frontiers were to be distributed.

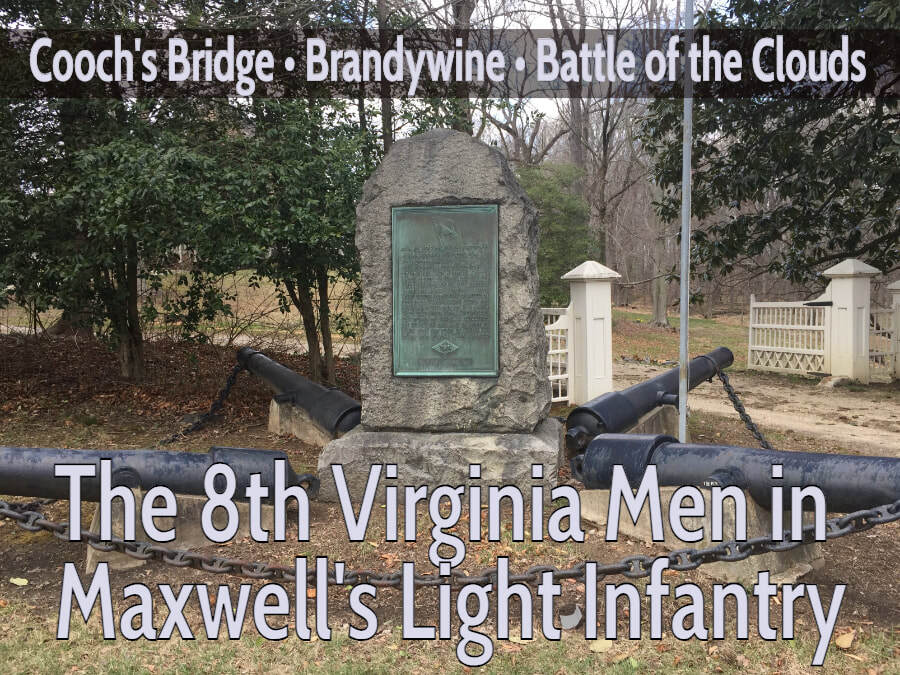

Agreeable to this new Act we received orders to march to Winchester, there to join the 12th Virga Regt commanded by Col. James Wood; pursuant to which orders we marched from Tygar's Valley in the begining of Aprill and proceeded with all expedition; which march we compleated in the space of eight days; after having rested a few days at Winchester we proceeded to join the Continental Army, which at that time lay partly in Morristown, partly at Boundbrook a small town on the Rarington [Raritan] river about 6 miles from New Brunswick, where His Excellency Generall Howe had his head quarters. May 19th we joined the grand army which then consisted of 20000 foot (chiefly composed of Virginians, Carolinians, and Pennsylvanians, the major part of whom were volunteers, altho’ for the most part disaffected to the rebel cause, they being for the most part convicts and indented servants, who had entered on purpose to get rid of their masters and of consequence of their commanders the first opportunity they can get of deserting) and about 300 light horse commanded by General Washington assisted by Lord Stirling, Major Generalls Stephens, Keyn [?], Sullivan; Brigadiers Weeden, Millenberg [Muhlenberg], Scott, Maxwell, Conway, which latter is a French man. Likewise a number of French officers who commanded in the Artillery, whose names or ranks I never had an opportunity of being acquainted with.

Nothing worthy of notice happened untill the 30th of that Inst on which the Continental Army decamped and retreated about 2 miles into the Blue [Watchung] Mountains and incamped at Middle Broock, where they were joined in a few days by the other part of the army that lay at Morristown.

Here they lay for some considerable time, during which they were employed in training their troops who were quite undisciplined and ignorant of every military art. Their Officers in general are equally ignorant as the private men, through which means they make but very little progress in learning. Wherefore it is generally believed by the unprejudiced part of the people that the rebells never will hazard a generall engagement, unless they are so hemmed up that they cannot have an opportunity of waving it; from which reason and the deplorable state the Country in generall is now reduced to, which in many places near to the seat of war is entirely destitute of labourers to cultivate the ground, insomuch that the women are necessitated for their own support to lay aside their wonted delicacy and take up the utensils for agriculture. From these and many other weighty reasons it is generally supposed that they cannot continue the war much longer.

Nothing material was transacted on either side till about the 24th of June, when a party of General Howe's army made a movement and advanced as far as Somerset, a small town lying on the Rarington betwixt Boundbroock and Princetown, which they plundered, and set fire to two small churches and several farm houses adjacent. General Washington upon receiving notice of their marching, detached 2 Brigades of Virginia troops and the like number of New Eng[lan]d to Pluckhimin, a small town about 10 miles from Somerset, lying on the road to Morristown. Here both parties lay for several days, during which time several slight skirmishes happened with their out scouts, without any considerable loss on either side. On the 29th the enemy retreated to Brunswick with their booty and we to our former ground in the Blue Mountain.

Next day His Excellency General Howe marched from Brunswick towards Bonumtown with his whole army, which was harassed on the march by Col. Morgan's Riflemen. As soon as General Howe had evacuated Brunswick, Mr Washington threw a body of the Jersey militia into it, and spread a report that he had forced them to leave it. July 2d there was a detachment of 150 Riflemen chosen from among the Virginia regiments, dispatched under the command of Capt. James [William] Dark a Dutchman, belonging to the eighth Virginia Regt to watch the enemy's motions. The same day this party, of which I was one, marched to Quibbleton [Quibbletown], and from thence proceeded towards [Perth] Amboy.

July 4th we had intelligence of the enemy's being encamped within a few miles of Westfield; that night we posted ourselves within a little of their camp and sent an officer with 50 men further on the road as a picquet guard, to prevent our being surprised in the night. Next morning a little before sun rise the British army before we suspected them, were upon pretty close on our picquet before they were discovered, and fired at a negroe lad that was fetching some water for the officer of sd guard, and broke his arm. Upon which he ran to the picquet and alarmed them, affirming at the same time that there was not upwards of sixty men in the party that fired at him. This intelligence was directly sent to us, who prepared as quick as possible to receive them and assist our picquet who was then engaged, in order for which, as we were drawing up our men, an advanced guard of the enemy saluted us with several field pieces, which did no damage. We immediately retreated into the woods from whence we returned them a very brisk fire with our rifles, so continued firing and retreating without any reinforcement till about 10 oClock, they plying us very warmly both with their artillery and small arms all the time; about which time we were reinforced with about 400 Hessians (who had been taken at sea going over to America & immediately entered into the Continental service) and three brass field pieces under the command of Lord Stirling. They drew up immediately in order to defend their field pieces and cover our retreat, and in less than an hour and a half were entirely cut off; scarce sixty of them returned safe out of the field; those who did escape were so scattered over the country that a great number of them could not rejoin the Army for five or six days, whilst the Kings troops marched off in triumph with three brass field pieces and a considerable number of prisoners, having sustained but very little loss on their side.