- Published on

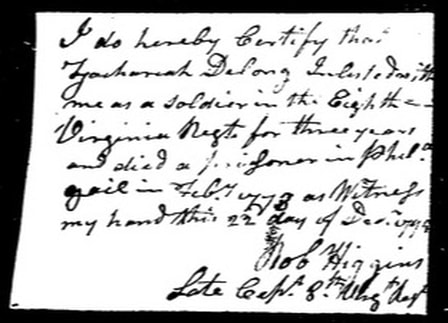

Two posts ago, I featured the house of Captain Robert Higgins in Moorefield, West Virginia. Here is a note authored by Higgins in support of a post-war bounty land warrant issued to the heirs of one of his soldiers, Zachariah DeLong. I don't know much about DeLong, but the story we have is a sad one.

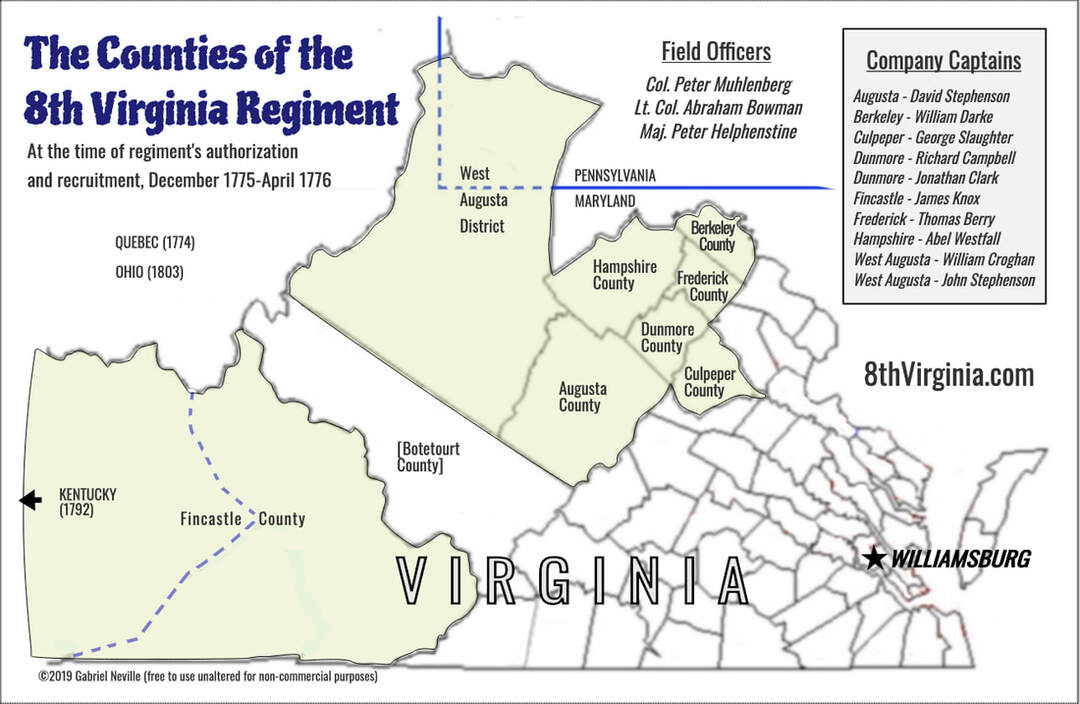

In the fall of 1776, the enlistments of an entire company of the 8th expired. (This was John Stephenson's company, which was formed in 1775 when terms were just a year.) Short a company, Colonel Muhlenberg proposed his brother-in-law, Francis Swain (the regiment's adjutant), be made a captain. Washington rejected Muhlenberg's suggestion and promoted Lt. Robert Higgins instead. Higgins came from Capt. Abel Westfall's Hampshire County-raised company and may have been the senior surviving lieutenant in the regiment. That would explain his promotion. Higgins spent the next six months diligently attempting to recruit a new company from scratch. The euphoria of 1776, however, had been replaced by the cold reality that nearly half of the original regiment had already died, deserted, or become very sick from malaria. Higgins was never able to recruit more than about 15 men. Zachariah DeLong was one of the brave souls who signed up.

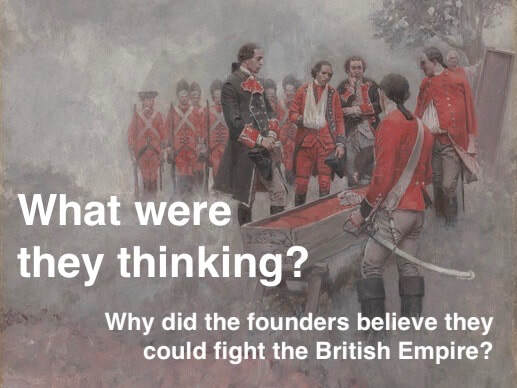

Higgins brought his tiny company to the main army late in September of 1777 and quickly went into combat at Germantown on October 4. Higgins and many others were captured when they followed Major William Darke into the thick morning fog just before friendly fire put the rest of the army into a retreat. Unlike Higgins, who was a veteran of the 1776 campaign, DeLong was in Washington's Army for just a few days before he was captured.

As an officer, Higgins was treated better by the British than enlisted men like DeLong. DeLong, like thousands of others, was held in conditions so terrible he could not survive them. Higgins signed at least three notes of this kind, attesting that soldiers like DeLong had indeed served under him before dying of rampant disease in a filthy British jail only four months after their capture.

Peter Muhlenberg, by the way, became a brigadier general at about the same time Higgins became a captain. He appointed Francis Swain his brigade major. Swain was terrible at the job and eventually washed out of the army.

Thanks to Tom Higgins of Shelbyville, Kentucky, for this document.

(Updated 3/29/20)

Read More: "Captain Higgins' House (8/30/15)"

In the fall of 1776, the enlistments of an entire company of the 8th expired. (This was John Stephenson's company, which was formed in 1775 when terms were just a year.) Short a company, Colonel Muhlenberg proposed his brother-in-law, Francis Swain (the regiment's adjutant), be made a captain. Washington rejected Muhlenberg's suggestion and promoted Lt. Robert Higgins instead. Higgins came from Capt. Abel Westfall's Hampshire County-raised company and may have been the senior surviving lieutenant in the regiment. That would explain his promotion. Higgins spent the next six months diligently attempting to recruit a new company from scratch. The euphoria of 1776, however, had been replaced by the cold reality that nearly half of the original regiment had already died, deserted, or become very sick from malaria. Higgins was never able to recruit more than about 15 men. Zachariah DeLong was one of the brave souls who signed up.

Higgins brought his tiny company to the main army late in September of 1777 and quickly went into combat at Germantown on October 4. Higgins and many others were captured when they followed Major William Darke into the thick morning fog just before friendly fire put the rest of the army into a retreat. Unlike Higgins, who was a veteran of the 1776 campaign, DeLong was in Washington's Army for just a few days before he was captured.

As an officer, Higgins was treated better by the British than enlisted men like DeLong. DeLong, like thousands of others, was held in conditions so terrible he could not survive them. Higgins signed at least three notes of this kind, attesting that soldiers like DeLong had indeed served under him before dying of rampant disease in a filthy British jail only four months after their capture.

Peter Muhlenberg, by the way, became a brigadier general at about the same time Higgins became a captain. He appointed Francis Swain his brigade major. Swain was terrible at the job and eventually washed out of the army.

Thanks to Tom Higgins of Shelbyville, Kentucky, for this document.

(Updated 3/29/20)

Read More: "Captain Higgins' House (8/30/15)"

This attack on the Chew House slowed the Continental advance during the Battle of Germantown. This and other causes of confusion led to a friendly fire incident. Zachariah DeLong and other advancing 8th Virginia men were captured along with the entire 9th Virginia Regiment when the rest of the army retreated. (Image: unknown artist after a painting by Alonzo Chappel)

More from The 8th Virginia Regiment