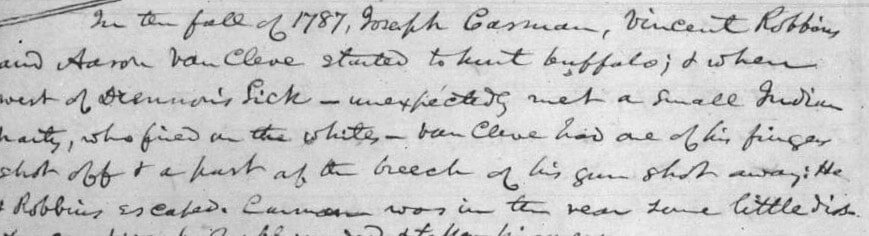

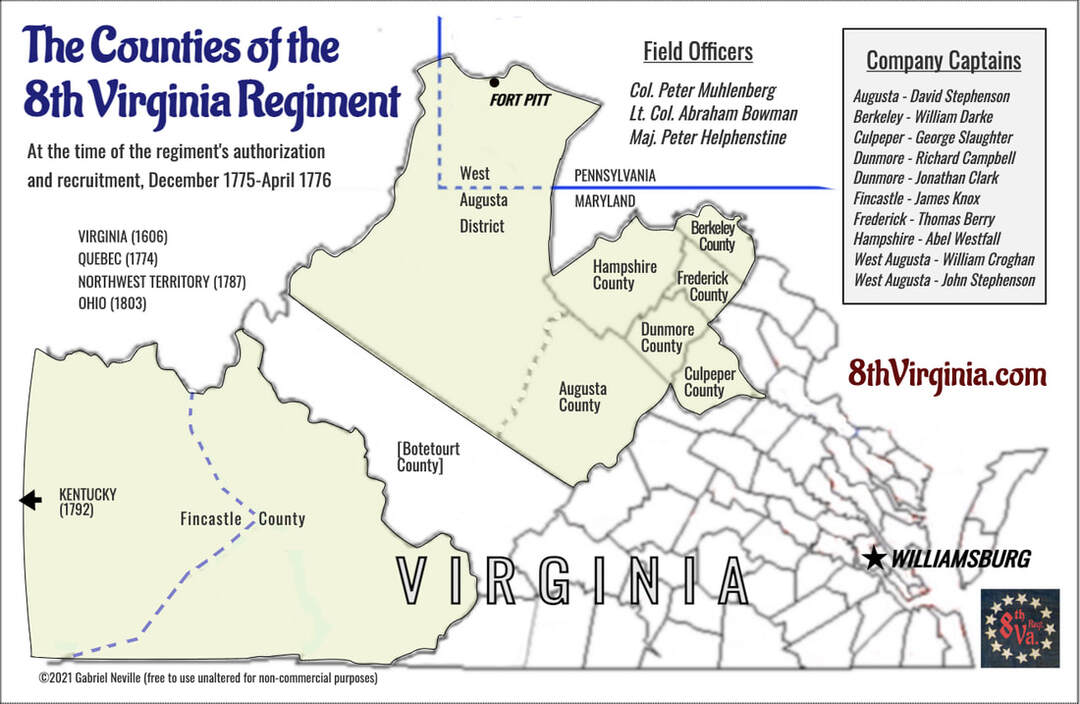

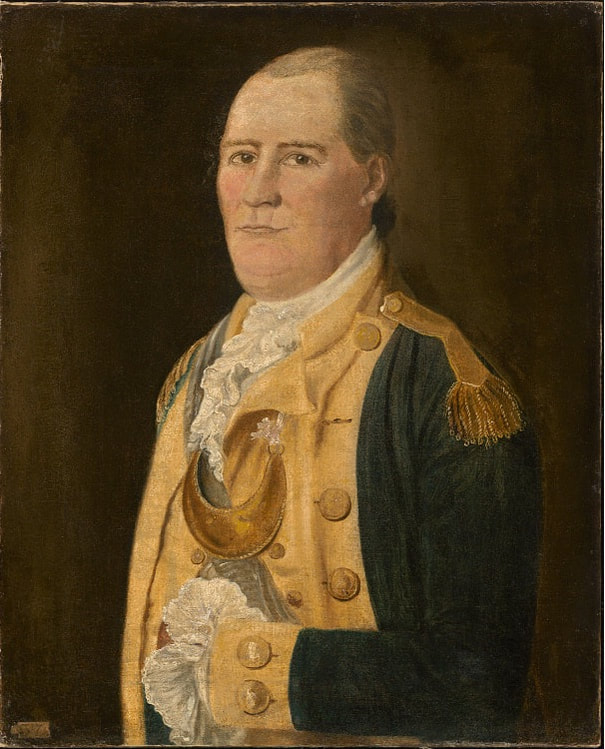

The Canada question, on the other hand, is now settled. The very first companies of Congress-authorized “Continental” troops included two companies of riflemen raised in the Shenandoah Valley in July of 1775. I have hoped to find just one 8th Virginia soldier who was in Capt. Daniel Morgan’s Frederick County company. But was there one? Yes. Daniel Anderson enlisted in Morgan’s rifle company in July of 1775 and was with him at Boston and the attack on Quebec. He was wounded at Quebec in the chest and the right arm, captured, and held prisoner for months. He was eventually exchanged and then discharged at Elizabeth, New Jersey.

In February 1777 he enlisted again under Morgan, who was now the colonel of the 11th Virginia. There is no record of Anderson in the 11th Virginia rolls, however, because he was promoted to sergeant and transferred into Capt. Thomas Berry’s company of the 8th Virginia. Anderson was with the 8th through Germantown, Whitemarsh, Valley Forge, and Monmouth. He was discharged on February 2, 1779. He then received a state commission as a lieutenant in the Western Battalion of Virginia state troops (state regulars—not militia and not Continentals), probably fighting Indians as far west as Indiana under Col. Joseph Crockett. Other 8th Virginia men were on the frontier as well, serving as far west as Illinois. After the war, Anderson settled in Shenandoah County, Virginia and lived the rest of his life there.

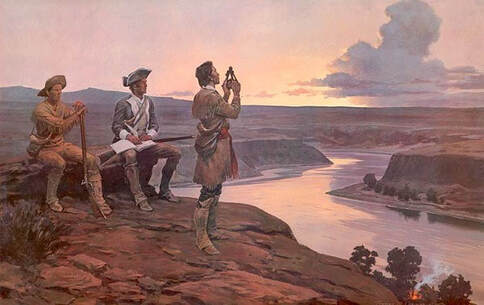

So what can we claim for the length and breadth of the regiment’s service? “From Canada to Florida” is still a stretch beyond what we can prove. To the Florida line? Still too far. Until we can prove more, we’ll have to settle for “From Canada nearly to Florida.” Can we also say, “From the Atlantic to the Mississippi?” Not yet, but it’s entirely plausible. Regardless, the range of the 8th Virginia’s men is impressive. Almost all of that movement was covered on foot.

In retirement, Daniel Anderson’s wounds kept him from performing hard labor—even the work of a subsistence farmer. Still, he somehow had to support his wife and three disabled children. “I am by occupation a farmer,” he said in 1820, “but owing to wounds and age I am unable to follow it. I have my wife living with me, aged 57 years; 1 daughter, aged 23 years, a cripple; and two dumb children, both simple, one a girl aged 14 the other a boy aged 27. The reason for his older daughter’s disability was her being “so much afflicted with Cancers that she has not been out of the house for 16 months.” The word "dumb" in those days still meant "mute." "Simple" meant intellectually disabled.

There were no federal pensions yet, but he applied to the Virginia legislature for pension on the basis of his own service-connected disability. He made his case before a judge. His conclusion was recorded by the court in the third person: “The prayer of your petitioner therefore is that your honorable body will pass an Act allowing such pension as in your wisdom you may deem sufficient to enable him to end his few remaining days in praying, as he will ever pray for the success and prosperity of his native state and country to secure the liberties of which in his younger days he voluntarily encountered the perils of war and shed his blood in her service.”

The date of his petition isn’t shown, but it was supported by notes from doctors and a letter from Daniel Morgan in 1796: “The bearer of this Dan’l. Anderson Inlisted a soldier with me in the year 1775 march’d with me to Boston & from thence to Quebec – was with me in the storm of the garison, on the last Day of Dec’r. when Gen;l Montgomery fell. He Rec’d two wounds in the action, one in the Breast & one in his Arm which Doctor senseny & Doctor Balwin certyfies that said wounds has so disabled him as to Rendered unfit for Hard Labour & thinks Him a proper object for a Pension.”

"Doctor Balwin" was Cornelius Baldwin, the former surgeon of the 8th Virginia. Anderson received his state pension and later received federal support as well. He died on November 6, 1840.

UPDATE: Thanks to Carolyn Brown Butler who alerted us to

the pension of her ancestor William Smith. Smith, after his time in the 8th, served under George Rogers Clark and (former 8th VA captain) George Slaughter. He was sent by Clark as an express rider to the Iron Banks, six miles below the mouth of the Ohio on the Mississippi. So now we can say that at least one 8th Virginia man served from "the Atlantic to the Mississippi."