RSVP HereOn June 1, 1778, Christopher Moyer and Philip Huffman escaped from the enemy. They had both been captured at the Battle of Germantown. Now free, they rejoined the 8thVirginia Regiment and continued the fight.

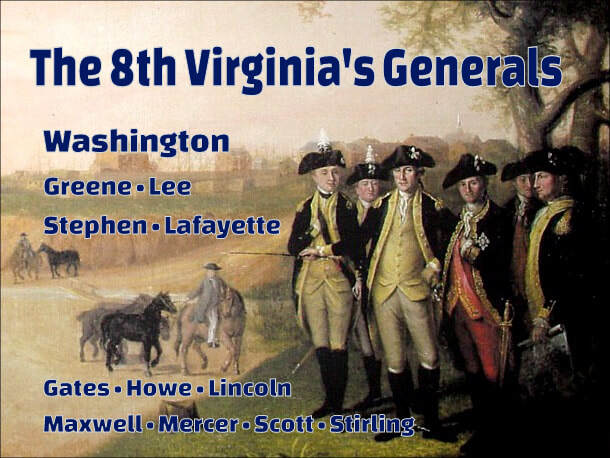

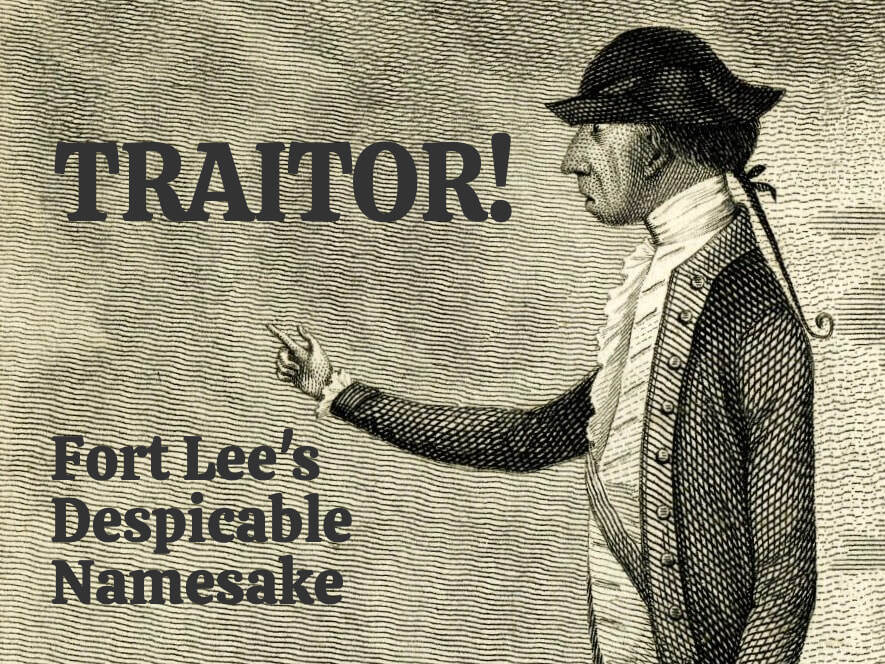

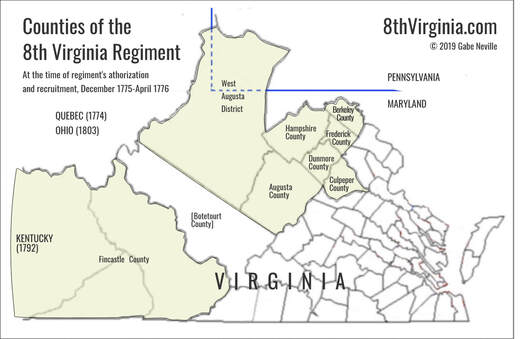

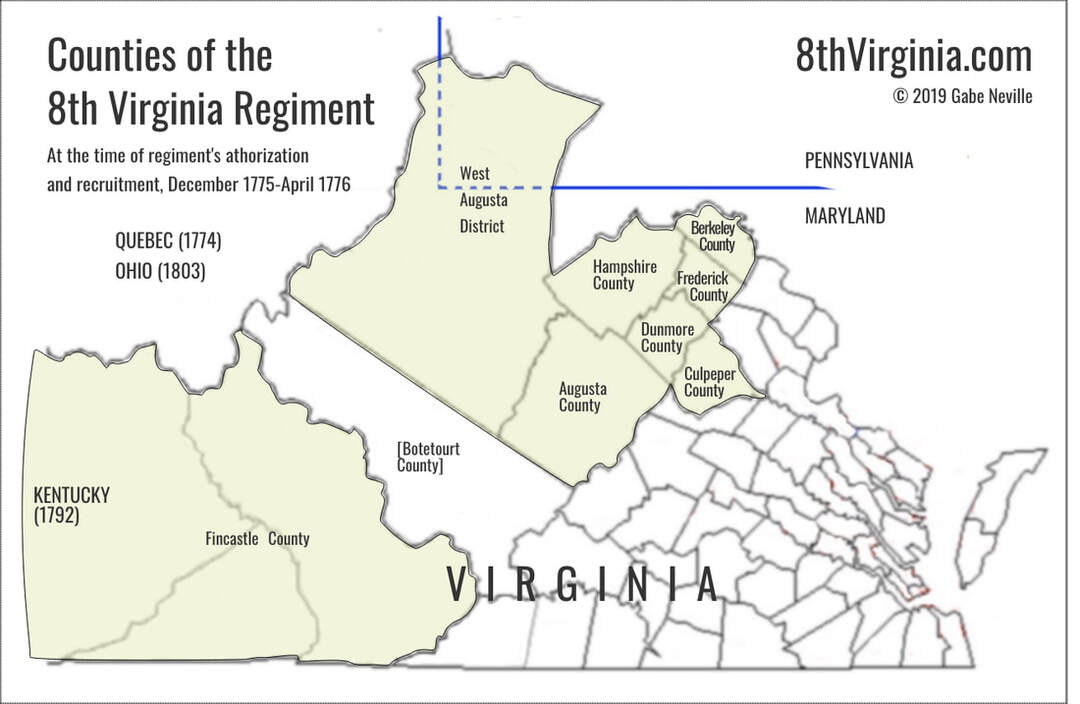

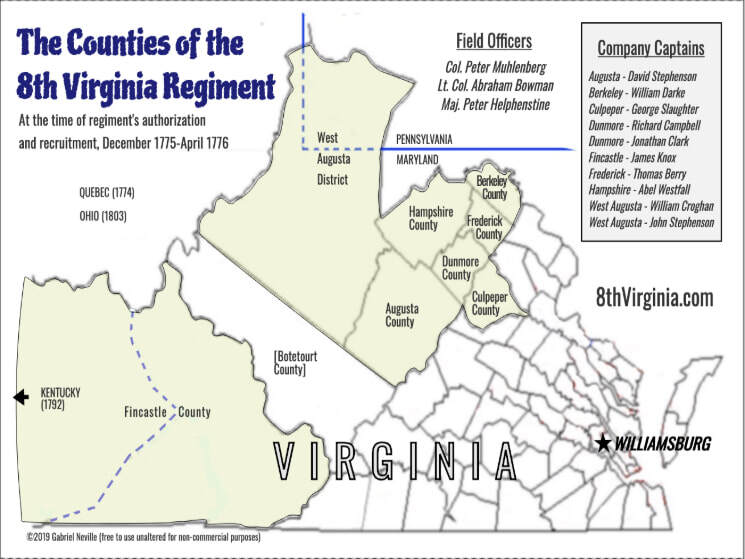

The Virginia Convention had intended the 8thVirginia to be a German regiment, recruited on the frontier and led by German field officers: Col. Peter Muhlenberg, Lt. Col. Abraham Bowman and Maj. Peter Helphenstine. The regiment was never purely German, but the lower Shenandoah Valley (where several companies were raised) were indeed heavily German.

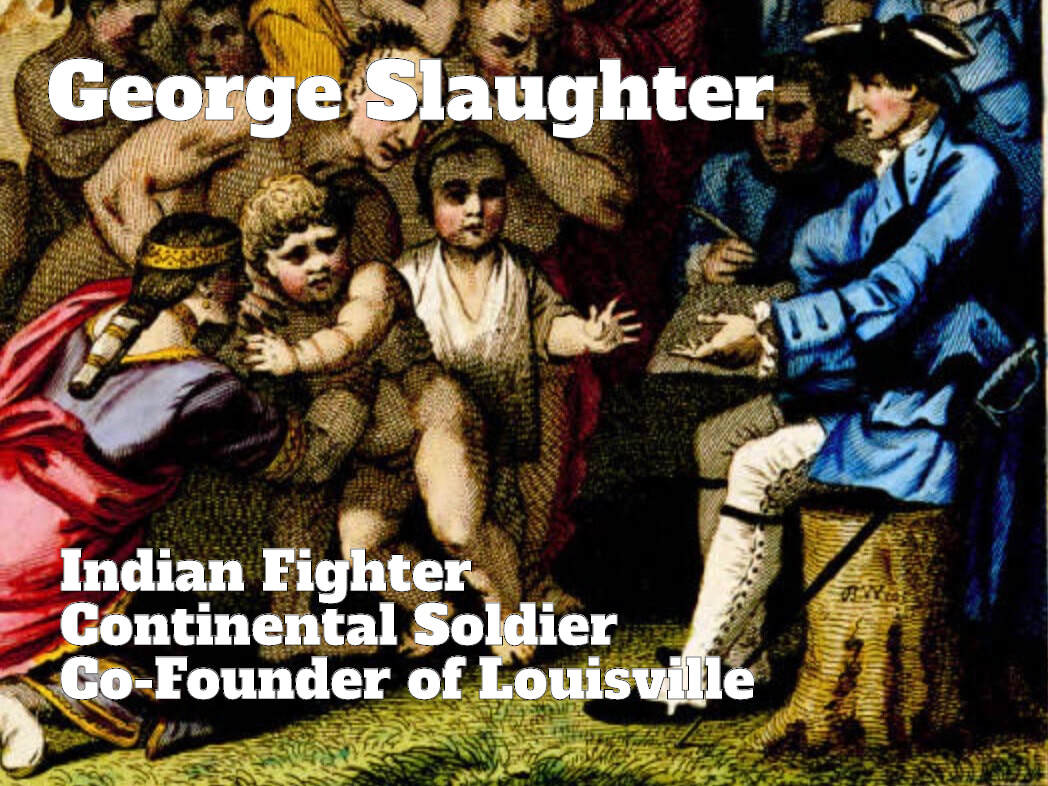

Moyer and Huffman were from Culpeper County, adjacent to an older settlement of Germans who had come by a different Route: Germanna. Was the 8thVirginia’s Culpeper company, led by Culpeper Minutemen veteran George Slaughter, assigned to the regiment because of the Germanna settlement? Moyer was a Germanna descendent. Hufman was probably not. Slaughter might have been.

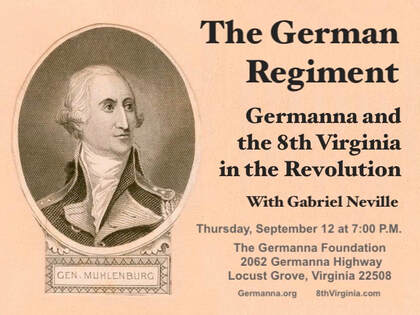

Gabe Neville will tell the fascinating story of the 8thVirginia and ask “Just how German was it?” in a presentation at the Germanna Foundation’s Hitt Archeology Center on Thursday, September 12, 2019. The event is free and open to the public.

From the Foundation:

Mr. Gabe Neville will present on George Slaughter, a Captain of the Culpeper company of the 8th Virginia Regiment. The 8th Virginia was originally designated “the German Regiment” by the Virginia Convention. Though the 8th Virginia did not develop into a uniformly German regiment, the Convention’s intent may explain Culpeper’s inclusion in the regiment’s recruitment area and Slaughter’s commission as a captain. He will mention other Culpeper soldiers with Germanna connections and complete their stories by following them into the Tennessee and Kentucky post-war frontiers.

Gabe Neville has been researching the history of the Revolutionary War’s 8th Virginia Regiment for more than 20 years. Working toward an eventual published history, he gives speeches, maintains a blog at

8thVirginia.com, and publishes essays on related subjects. He also writes occasionally on public policy issues. A former journalist and congressional staffer, he is now Senior Advisor at Covington & Burling, a Washington-based international law firm. Originally from Pennsylvania, he lives with his family in Fairfax County, Virginia.

This event is FREE and open to the public and will take place in the Hitt Archaeology Center, located next to the Fort Germanna Visitor Center. There will be time available for questions after the presentation

RSVP Here